LCVP (United States)

The landing craft, vehicle, personnel (LCVP) or Higgins boat was a landing craft used extensively in amphibious landings in World War II. Typically constructed from plywood, this shallow-draft, barge-like boat could ferry a roughly platoon-sized complement of 36 men to shore at 9 knots (17 km/h). Men generally entered the boat by climbing down a cargo net hung from the side of their troop transport; they exited by charging down the boat's lowered bow ramp.

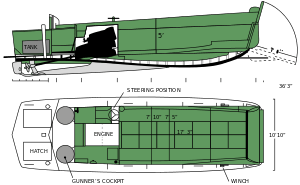

LCVP side elevation and plan | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders: | Higgins Industries and others |

| Operators: | |

| Built: | 1942–1945 |

| Completed: | More than 23,358 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Landing craft |

| Displacement: | 18,000 lb (8,200 kg) light |

| Length: | 36 ft 3 in (11.05 m) |

| Beam: | 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m) |

| Draft: |

|

| Propulsion: | Gray Marine 6-71 Diesel Engine, 225 hp (168 kW) or Hall-Scott gasoline engine, 250 hp (186 kW) |

| Speed: | 12 knots (14 mph; 22 km/h) |

| Capacity: | 6,000 lb (2,700 kg) vehicle or 8,100 lb (3,700 kg) general cargo |

| Troops: | 36 troops |

| Crew: | 4: Coxswain, engineer, bowman, sternman |

| Armament: | 2 × .30 cal. (7.62 mm) Browning machine guns |

The craft was designed by Andrew Higgins based on boats made for operating in swamps and marshes. More than 23,358 were built, by Higgins Industries and licensees.[1]

Taking the last letter of the LCVP designation, sailors often nicknamed the Higgins Boat the "Papa Boat" or "Peter Boat" to differentiate it from other landing craft such as the LCU and the LCM, with the LCM being called the "Mike Boat."

Design

At just over 36 ft (11 m) long and just under 11 ft (3.4 m) wide, the LCVP was not a large craft. Powered by a 225-horsepower Diesel engine at 12 knots, it would sway in choppy seas, causing seasickness. Since its sides and rear were made of plywood, it offered limited protection from enemy fire but also reduced cost and saved steel. The Higgins boat could hold either a 36-man platoon, a jeep and a 12-man squad, or 8,000 lb (3.6 t) of cargo. Its shallow draft (3 feet aft and 2 feet, 2 inches forward) enabled it to run up onto the shoreline, and a semi-tunnel built into its hull protected the propeller from sand and other debris. The steel ramp at the front could be lowered quickly. It was possible for the Higgins boat to swiftly disembark men and supplies, reverse itself off the beach, and head back out to the supply ship for another load within three to four minutes.

Armor was a problem, but also other problems found later were that the boat could not go through shallow water and reefs. Other vehicles were created to meet those drawbacks in amphibious operations.

The Higgins boat was built in New Orleans.[2]

History

Andrew Higgins started out in the lumber business, but gradually moved into boat building, which became his sole operation after the lumber transport company he was running entered bankruptcy in 1930. Many sources say his boats were intended for use by trappers and oil-drillers; occasionally, some sources imply or even say that Higgins intended to sell the boats to individuals intending to smuggle illegal liquor into the United States.[3][4][5]

Higgins' financial difficulties, and his association with the U.S. military, occurred around the time Prohibition was repealed, which would have ruined his market in the rum-running sector; the U.S. Navy's interest in the boats was in any case providential, though Higgins proved unable to manage his company's good fortune.[1]

The United States Marine Corps was always interested in finding better ways to get men across a beach in an amphibious landing. They were frustrated that the Navy's Bureau of Construction and Repair could not meet its requirements and began to express interest in Higgins' boat. When tested in 1938 by the Navy and Marine Corps, Higgins' Eureka boat surpassed the performance of a Navy-designed boat, and was tested by the services during fleet landing exercises in February 1939. Satisfactory in most respects, the boat's major drawback appeared to be that equipment had to be unloaded, and men disembarked, over the sides, thus exposing them to enemy fire in combat situations and making unloading time-consuming and complex. However, that was the best available boat design, and it was put into production and service as the landing craft, personnel (large), abbreviated as LCP(L). The LCP(L) had two machine gun positions at the bow.

The LCP(L), commonly called the "U-boat" or the "Higgins" boat, was supplied to the British (from October 1940), to whom it was initially known as the "R-boat" and used for commando raids.

The Japanese had been using ramp-bowed landing boats like Daihatsu-class landing craft in the Second Sino-Japanese War since the summer of 1937—boats that had come under intense scrutiny by Navy and Marine Corps observers at the Battle of Shanghai in particular, including from future general, Victor H. Krulak.[6] When Krulak showed Higgins a picture and suggested that Higgins develop a version of the ramped craft for the Navy, Higgins, at his own expense, started his designers working on adapting the idea to the boat design. He then had three of the craft built, again at his own expense.[7]

On May 26, 1941, Cdr. Ross Daggett, from BuShip, and Maj. Ernest Linsert, of the Marine Equipment Board, witnessed the testing of the three craft. One involved off-loading a truck; another the embarking and disembarking of 36 of Higgins' employees, simulating troops. This craft later was designated LCVP—Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel.[7]

Legacy

The Supreme Allied commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, declared the Higgins boat to have been crucial to the Allied victory on the European Western Front and the previous fighting in North Africa and Italy:[1]

Andrew Higgins ... is the man who won the war for us. ... If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different.[8][9][10]

The Higgins boat was used for many amphibious landings, including Operation Overlord on D-Day in Nazi German-occupied Normandy, and previously Operation Torch in North Africa, the Allied invasion of Sicily, Operation Shingle and Operation Avalanche in Italy, Operation Dragoon, as well as in the Pacific Theatre at the Battle of Guadalcanal, the Battle of Tarawa, the Battle of the Philippines, the Battle of Iwo Jima and the Battle of Okinawa.

LCVPs fitted with a roof and an Oerlikon 20 mm cannon were used by the French Navy’s Dinassauts during the First Indochina War to patrol the Mekong, along with other US-origin landing craft.[11]

Surviving examples

Only a few Higgins boats have survived, often with substantial modifications for post-War use. A remarkably preserved Higgins boat, with the original Higgins motor, was discovered in a boat yard in Valdez, Alaska, and moved to the Museum of World War II just outside Boston in 2000. It had been used as a fishing boat in very shallow areas but, except for an easily removed addition to the cockpit, had not been altered; all of the armor plate was complete, as were gauges and equipment. The only restoration was a repainting to the original color.[12][13]

An original Higgins boat discovered in Normandy has been professionally restored by the North Carolina Maritime Museum for the First Division Museum at Cantigny Park in Wheaton, Illinois.[14] This Higgins boat was located in Vierville-sur-Mer, Normandy, by Overlord Research, LLC, a West Virginia company formed in 2002 for the purpose of locating, preserving, and returning WWII artifacts to the United States.[15] Overlord purchased the vessel from its French owners and then transported the Higgins boat to Hughes Marine Service in Chidham, England, for initial evaluation and restoration. During this evaluation, the First Division Museum acquired the Higgins boat from Overlord Research, LLC, and moved the vessel to Beaufort, North Carolina, for extensive restoration.[16] It was then acquired by the Collings Foundation and is now on display at the American Heritage Museum in Stow, Massachusetts.[17]

An original LCVP is on display at the National Museum of the United States Army in Fort Belvoir, Virginia.[18] It was located by Overlord Research, LLC, on the Isle of Wight and acquired by the company. It was transported to Hughes Marine Service, where it underwent extensive restoration. Upon completion of the restoration work to standards set by the United States Army Center of Military History, this Higgins boat was purchased by the Center of Military History for future display in the museum.

An original LCVP is on display at the National Museum of the United States Navy in Washington, D.C.[19]

An original LCVP is under restoration at the Maisy battery in Grandcamp-Maisy, Normandy.[20] It was found in a farmyard in Isigny sur Mer in 2008.

An original LCVP is on display at The D-Day Story in Portsmouth, Hampshire.[21] It was restored by Hughes Marine Service.

An original LCVP is seaworthy with Challenge LCVP in Rouen, Normandy. It was constructed in 1942 and may have taken part in landings in North Africa and in Italy during World War II.[22]

An original LCVP is in storage with the WWII Veterans History Project in Clermont, Florida. It was acquired by the organization in April 2020 and is currently awaiting restoration.[23]

An original LCVP is undergoing restoration at the Indiana Military Museum in Vincennes, Indiana.[24] The stern of the boat displays AG 39 and was presumably attached to the USS Menemsha (AG-39), a weather patrol ship in the North Atlantic, during WWII. It was later used, commercially, in Vallejo, California, before being re-located previously to Port St. Lucie, Florida.

An original LCVP is on display at the Motts Military Museum in Groveport, Ohio. It is from the USS Cambria (APA-36), which survived seven Pacific Theatre invasions.[25]

An original LCVP is on display at the Roberts Armory Museum in Rochelle, Illinois.[26]

One is undergoing restoration at the Louisiana Military Hall of Fame and Museum in Abbeville, Louisiana.[27]

A replica Higgins boat, built in the 1990s using the original specifications from Higgins Industries, is on display in The National WWII Museum in New Orleans.[28]

In July 2018, a 1942 LCVP designed in a similar fashion to the Eureka model was discovered in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta of California. Having been left unattended in brackish waters for at least 40 years, restoration was not required and post survey, the hull was confirmed as perfectly sound. It is currently being operated under its own power by owner with the original Chrysler Crown Marine engine and unmodified transmission. Features include the original gauges, Bureau of Ships ID 72530, steel bunks, fire extinguisher, boat horn and several other original features all of which are in working order.

An intact surviving example is known to lie beached at King Edward Point on South Georgia although this craft is in poor condition due to the Antarctic environment.

Postwar

A post-war version is in use at the Regional Military Museum in Houma, Louisiana.[29]

A post-war example utilising fibreglass construction instead of plywood is in the Shopland Collection, located near Bristol, England. It has been used in the filming of Saving Private Ryan and several documentaries about Operation Overlord. This vessel is currently stored awaiting restoration.[30]

The USS LST-325 operates two LCVPs built in the 1950s.

In popular culture

The 1956 movie Away All Boats shows the role of Higgins boats in beach landings. The novel of the same name was written by a former naval officer who served on an attack transport and gives detailed information on their use.[31]

The use of these boats during the D-day invasions at Normandy is shown in the feature films The Longest Day and Saving Private Ryan. The boats were also used in a scene during the 1985 film Invasion USA,[32] in which communist guerrillas land on a Florida beach.

See also

References

- Herman, Arthur. Freedom's Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, Random House, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4000-6964-4. pp. 204-206

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-02-18. Retrieved 2018-02-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kenneth Macksey (20 July 2013). Commando: Special Forces in World War II. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-402-8.

- Jeter A. Isely; Philip A. Crowl (8 December 2015). U.S. Marines and Amphibious Warfare. Princeton University Press. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-1-4008-7946-5.

- "Acquisition awards reward excellence and innovation". Archived from the original on 2018-04-02. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- Goldstein, Richard. "Victor H. Krulak, Marine Behind U.S. Landing Craft, Dies at 95" Archived 2017-07-30 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times, January 4, 2009. Accessed January 5, 2009.

- Strahan, Jerry E. (1994). Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-2339-0.

- "The Higgins Boat". Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- "MAHS Salisbury/Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP)". Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- "LST 494 LCVPs (Higgins Boats)". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- Guillaume, Pierre; Escalle, Elisabeth (2006). Mon âme à Dieu, mon corps à la Patrie, mon honneur à moi: Mémoires (in French). Paris: Plon. ISBN 978-2259204422.

- Morgan, Thomas J. "D-Day saga on display as never before at World War II Museum". The Providence Journal, May 31, 2014.

- "PACIFIC FRONT". The International Museum of World War II. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Olsen, George. "Maritime Museum-restored LCVP handed over to 1st Division Museum". Public Radio East. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Record for Overlord Research, LLC, West Virginia Secretary of State, Business Organization Information System.

- Price, Jay. McClatchy Newspapers; "Rare Boat Crucial to Winning WWII Being Restored". The Sunday Gazette-Mail, Page 12A, Charleston, West Virginia, September 7, 2008.

- "Restoration & Acquisition Report 2017". The Collings Foundation 2017-2018 Newsletter. Stow, Massachusetts, USA: Collings Foundation. 30 November 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "GLOBAL WAR". National Museum of the United States Army. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "LCVP". Historic Naval Ships Association. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "LCVP Restoration". Maisy Battery. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "A closer look at our collections: LCVP landing craft". YouTube. 1 May 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Historique du L9386". Challenge LCVP Higgins Boat (in French). Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "WWII LCVP RESTORATION PROJECT". WWII Veterans History Project. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Exhibit Sponsorship". Indiana Military Museum. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "World War II". Motts Military Museum. Archived from the original on 18 November 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP) "Higgins Boat"". RobertsArmory.com. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Projects". Louisiana Military Hall of Fame and Museum. Louisiana Military Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- "New Orleans: Home of the Higgins Boats" (PDF). National World War II Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

- "SCHEDULE A RIDE ON OUR LCVP!". The Regional Military Museum. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- "Landing Craft Vehicle Personnel (LCVP)". The Shopland Collection. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- "AWAY ALL BOATS by Kenneth Dodson". Kirkus Reviews. Archived from the original on 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- Robert Pope (25 December 2016). "Watch Invasion USA 1985 Watch Movies Online Free" – via YouTube.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to LCVP. |

- Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1940–1945: LCVP

- History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II Volume I Chapter 3: "Development of Landing Craft"

- USS Rankin (AKA-103): LCVP

- USS LST 494 Higgins Boats

- Higgins Industries Motor Torpedo Boat Diagram Collection in the LOUISiana Digital Library

- Armagnac, Alden P. (October 1941). "New Tools for Army Power". Popular Science: 76–77. Photos of early testing of Higgins's first landing boats.