L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows (/ˈlænsi ˈmɛdoʊz/) is an archaeological site on the northernmost tip of the Great Northern Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Archaeological evidence of a Norse presence was discovered at L'Anse aux Meadows in the 1960s. It is the only confirmed Norse site in or near North America outside of the settlements found in Greenland.[1][2]

| L'Anse aux Meadows | |

|---|---|

Recreated Norse buildings at L'Anse aux Meadows | |

| Coordinates | 51°35′47″N 55°32′00″W |

| Website | www |

| Official name: L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | vi |

| Designated | 1978 (2nd session) |

| Reference no. | 4 |

| Country | Canada |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Official name: L'Anse aux Meadows National Historical Site of Canada. | |

| Designated | 28 November 1968 |

Location of L'Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland | |

Dating to c. 1000, L'Anse aux Meadows is widely accepted as evidence of pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact. It is notable for its possible connection with Leif Erikson, and with the Norse exploration of North America. It was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1978.[3]

Etymology

L'Anse aux Meadows is a French-English name which can be translated as the bay with the grasslands.[4] How the village itself came to be named "L'Anse aux Meadows" is debated. One possibility is that "L'Anse aux Meadows" is a corruption of the French designation L'Anse aux Méduses, which means "Jellyfish Cove".[5][6][4] The shift from Méduses to "Meadows" may have occurred because the landscape in the area tends to be open, with meadows.[7]. A more recent supposition is that it is derived from "L'Anse à la Médée", or "The Medea's Cove" [8], the name it bears on an 1862 French naval chart. Whether Medea or Medusa, it is possible that the name refers to a French naval vessel.[9]

History

Pre-European settlements

Before the Norse arrived in Newfoundland, there is evidence of aboriginal occupations in the area of L'Anse aux Meadows, the oldest dated at roughly 6,000 years ago. None were contemporaneous with the Norse occupation. The most prominent of these earlier occupations was by the Dorset people, who predated the Norse by about 200 years.[10]

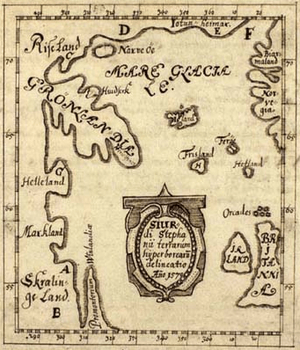

Norse site (c. 1000)

• Land of the Risi (a mythical location)

• Greenland

• Helluland (Baffin Island)

• Markland (the Labrador Peninsula)

• Land of the Skrælingjar (location undetermined)

• Promontory of Vinland (the Great Northern Peninsula)

The Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows has been dated to approximately 1,000 years ago (carbon dating estimate 990–1050 CE),[12] an assessment that tallies with the relative dating of artifact and structure types.[13]

Today the area mostly consists of open, grassy lands, but 1000 years ago there were forests that were convenient for boat-building, house-building and iron extraction.[14] The remains of eight buildings (labeled from A–J) were found. They are believed to have been constructed of sod placed over a wooden frame. Based on associated artifacts, the buildings were identified as dwellings or workshops. The largest dwelling (F) measured 28.8 m × 15.6 m (94 ft × 51 ft) and consisted of several rooms.[15] Three small buildings (B, C, G) may have been workshops or living quarters for lower-status crew or slaves. Workshops were identified as an iron smithy (building J) containing a forge and iron slag,[16] a carpentry workshop (building D), which generated wood debris and a specialized boat repair area containing worn rivets.

Other things found at the site consisted of common everyday Norse items, including a stone oil lamp, a whetstone, a bronze fastening pin, a bone knitting needle and part of a spindle. Stone weights, which were found in building G, may have been part of a loom. The presence of the spindle and needle suggests that women as well as men inhabited the settlement.[17]

There is no way of knowing how many people lived at the site at any given time; archaeological evidence of the dwellings suggest it had the capacity of supporting 30 to 160 people.[18] The entire population of Greenland at the time was about 2,500, meaning that the L'Anse aux Meadows site was less than 10 percent of the Norse settlement on Greenland.[19] As Julian D. Richards notes: "It seems highly unlikely that the Norse had sufficient resources to construct a string of such settlements."[19]

Food remains included butternuts, which are significant because they do not grow naturally north of New Brunswick. Their presence probably indicates the Norse inhabitants traveled farther south to obtain them.[20] There is evidence to suggest that the Norse hunted an array of animals that inhabited the area. These included caribou, wolf, fox, bear, lynx, marten, all types of birds and fish, seal, whale and walrus. This area is no longer rich in game due in large part to the harsh winters. This forces the game to either hibernate or venture south as the wind, deep snow, and sheets of ice cover the area. These losses made the harsh winters very difficult for the Norse people at L'Anse aux Meadows.[21] This lack of game supports archaeologists' beliefs that the site was inhabited by the Norse for a relatively short time.

Eleanor Barraclough, a lecturer in medieval history and literature at Durham University,[22] suggests the site was not a permanent settlement, instead a temporary boat repair facility.[16] She notes there are no findings of burials, tools, agriculture or animal pens—suggesting the inhabitants abandoned the site in an orderly fashion.[23] According to a 2019 PNAS study, there may have been Norse activity in L'Anse aux Meadows for as long as a century.[24]

Connection with Vinland sagas

Adam of Bremen, a German cleric, was the first European to mention Vinland. In a text he composed around 1073, he wrote that

He [the Danish king, Sven Estridsson] also told me of another island discovered by many in that ocean. It is called Vinland because vines grow there on their own accord, producing the most excellent wine. Moreover, that unsown crops abound there, we have ascertained not from fabulous conjecture but from the reliable reports of the Danes.[25]

This excerpt is from a history Adam composed of the archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen who held ecclesiastical authority over Scandinavia (the original home of the Norse people) at the time.

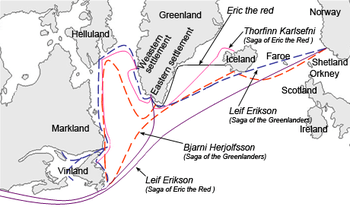

Norse sagas are written versions of older oral traditions. Two Icelandic sagas, commonly called the Saga of the Greenlanders and the Saga of Erik the Red, describe the experiences of Norse Greenlanders who discovered and attempted to settle land to the west of Greenland, which they called Vinland. The sagas suggest that the Vinland settlement failed because of conflicts within the Norse community, as well as between the Norse and the native people they encountered, whom they called Skrælingar.[26]

Modern archaeological studies have suggested that the L'Anse aux Meadows site was not Vinland itself, but rather was within a larger area called Vinland, which extended south from L'Anse aux Meadows to the St. Lawrence River and New Brunswick.[27] The L'Anse aux Meadows site served as an exploration base and winter camp for expeditions heading southward into the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[20][28] The settlements of Vinland mentioned in these two sagas, Leifsbudir (Leif Ericson) and Hóp (Norse Greenlanders), have both been claimed as the L'Anse aux Meadows site.[28][1]

Discovery and significance (1960–68)

_(5494474208).jpg)

In 1960, the archaeological remains of Norse buildings were discovered in Newfoundland by the Norwegian husband-wife team of explorer Helge Ingstad and archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad. Based on the idea that the Old Norse name "Vinland", mentioned in the Icelandic Sagas, meant "wine-land", historians had long speculated that the region contained wild grapes.[29] Because of this, the common hypothesis before the Ingstads' theories was that the Vinland region existed somewhere south of the northern Massachusetts coast, because that is roughly as far north as grapes grow naturally.[29] This is a false assumption. Wild grapes have grown and still grow along the coast of New Brunswick and in the St. Lawrence River valley of Quebec.[30] The archaeological excavation at L'Anse aux Meadows was conducted from 1960 to 1968 by an international team led by archaeologist Anne Stine Ingstad.

The Ingstads doubted this theory, saying "that the name Vinland probably means land of meadows...and includes a peninsula."[31] This speculation was based on the belief that the Norse would not have been comfortable settling in areas along the American Atlantic coast. This dichotomy between the two views could have possibly been due to the two historic ways in which the first vowel sound of "Vinland" could be pronounced. The word used in the sagas clearly relates to grapes. In fact, the discovery of butternuts in the Norse stratum of the bog on the site by Parks Canada archaeologists proves that the Norse ventured at least as far as the coast of New Brunswick, where butternuts grow (and have grown for centuries) alongside wild grapes. The Norse thus would have had contact with the grapes of the sagas.[30]

In 1960, George Decker, a citizen of the small fishing hamlet of L'Anse aux Meadows, led Helge Ingstad to a group of mounds near the village that the locals called the "old Indian camp". These mounds covered with grass looked like the remains of houses.[17] Helge Ingstad and Anne Stine Ingstad carried out seven archaeological excavations there from 1961 to 1968. They investigated the remains of eight buildings and the remains of perhaps a ninth.[32] They determined that the site was of Norse origin because of definitive similarities between the characteristics of structures and artifacts found at the site compared to sites in Greenland and Iceland from around 1000 CE.

L'Anse aux Meadows is the only confirmed Norse site in North America outside of Greenland.[2] It represents the farthest-known extent of European exploration and settlement of the New World before the voyages of Christopher Columbus almost 500 years later. Historians have speculated that there were other Norse sites, or at least Norse-Native American trade contacts, in the Canadian Arctic.[33] In 2012, possible Norse outposts were identified in Nanook at Tanfield Valley on Baffin Island,[34][35] as well as Nunguvik, Willows Island and the Avayalik Islands.[36][37] Point Rosee, in southwestern Newfoundland, shown by National Geographic and the BBC as a possible Norse site, was excavated in 2015 and 2016, without any evidence of a Norse presence being found.[2][38][39]

National historic site (1968–present)

In November 1968, the Government of Canada named the archaeological site a National Historic Site of Canada. The site was also named a World Heritage Site in 1978 by UNESCO. After L'Anse aux Meadows was named a national historic site, the area, and its related tourist programs, have been managed by Parks Canada. After the first excavation was completed, two more excavations of the site were ordered by Parks Canada. The excavations fell under the direction of Bengt Schonbach from 1973 to 1975 and Birgitta Wallace, in 1976. Following each period of excavation, the site was reburied to protect and conserve the cultural resources.

The national historic site remains of seven Norse buildings are on display. North of the Norse remains are reconstructed buildings, built in the late 20th century, as a part of a interpretive display for the national historic site. The remains of an aboriginal hunting camp is also located at the site, southwest of the Norse remains. Other amenities at the site includes picnic areas, and a visitor centre.

See also

References

- Hamilton, William B. (1996). Place Names of Atlantic Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-7570-3.

- Ingstad, Helge; Ingstad, Anne Stine (2000) [1991]. The Viking Discovery of America: The Excavation of a Norse Settlement in L'Anse Aux Meadows, Newfoundland. Breakwater Books. ISBN 978-1-55081-158-2.

- Wallace, Birgitta (2003): The Norse in Newfoundland: L'Anse aux Meadows and Vinland. Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, The New Early Modern Newfoundland: Part 2. Vol. 19, No. 1

- Wallace, Birgitta Linderoth (2006): The Saga of L'Anse aux Meadows. Historic Sites Association of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Birgitta Wallace, 2018 [15]

Notes

- Wallace, Birgitta (2 May 2005). "The Norse in Newfoundland: L'Anse aux Meadows and Vinland". The New Early Modern Newfoundland. 19 (1).

- Bird, Lindsay (30 May 2018). "Archeological quest for Codroy Valley Vikings comes up short – Report filed with province states no Norse activity found at dig site". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". UNESCO World Heritage Center.

L'Anse aux Meadows is the first and only known site established by Vikings in North America and the earliest evidence of European settlement in the New World. As such, it is a unique milestone in the history of human migration and discovery.

- Hamilton, William Baillie (1996). Place Names of Atlantic Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-8020-7570-3.

The name [L'Anse aux Meadows] is a French-English descriptive which can be translated as the bay with the grasslands.

- William B. Hamilton, The Macmillan book of Canadian place names, 2e édition (1978), Philip 118.

- Mentionné également par Lawrence Millman dans Coins perdus : un parcours dans l'Atlantique nord (titre original : Last Places), Terres d'aventure, 1995 ISBN 2-7427-0475-2.

- Wahlgren, Erik (2000). The Vikings and America. Thames & Hudson. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-500-28199-4.

- Horwitz, Tony (2008). A Voyage Long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World (1st ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Company. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-8050-7603-5.

- Marie-julie Gagnon, Cartes postales du Canada, éditions Michel Lafon, Montréal, Québec, 2017

- "History – Aboriginal Sites". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 15 May 2007.

- http://www.myoldmaps.com/renaissance-maps-1490-1800/4316-skalholt-map/4316-skalholt-map.pdf

- Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (2009). "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- Nydal, Reidar (1989). "A critical review of radiocarbon dating of a Norse settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, Canada". Radiocarbon. 31 (3): 976–985. doi:10.1017/S0033822200012613.

- Ingstad & Ingstad (2000), p. 135.

- Wallace, Birgitta (2 March 2018). "L'Anse aux Meadows". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- "L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site". Parks Canada. 30 March 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

Smelting hut—this small isolated building contained a furnace for producing iron from bog ore. A simple smelter stood in the middle of the floor. A charcoal kiln was nearby. The amount and type of slag found suggests that a single smelt took place. Very little iron was manufactured, only enough for making about 100 to 200 nails.

- "History – Discovery of the Site and Initial Excavations (1960–1968)". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. 4 April 2019.

- Kolodny, Annette (2012). In Search of First Contact: The Vikings of Vinland, the Peoples of the Dawnland, and the Anglo-American Anxiety of Discovery. Duke University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8223-5286-0.

- Richards, J. D. (2005). The Vikings: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 112. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780192806079.003.0011. ISBN 978-0-19-280607-9.

- "History – Is L'Anse aux Meadows Vinland?". L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. Archived from the original on 22 May 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

...Vinland was a country, not a place...

- Ingstad & Ingstad (2000), p. 134.

- "Eleanor Rosamund Barraclough". The Guardian. February 2017.

- Barraclough, Eleanor Rosamund (2016). Beyond the Northlands: Viking Voyages and the Old Norse Sagas. Oxford University Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-19-100448-3.

- Forbes, Véronique; Girdland-Flink, Linus; Ledger, Paul M. (10 July 2019). "New horizons at L'Anse aux Meadows". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (31): 15341–15343. doi:10.1073/pnas.1907986116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6681721. PMID 31308231.

- Perkins, R.M. (June 1974). "Norse Implications". The Geographical Journal. 140 (2): 199–205. doi:10.2307/1797075. JSTOR 1797075.

- Murrin, John M.; Johnson, Paul E.; McPherson, James M.; Fahs, Alice; Gerstle, Gary (2008). Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Compact (5th ed.). Thomson Wadsworth. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-495-41101-7.

- Hurst, David Thomas (2013). "L'Anse aux Meadows: The Viking and the Native American". Exploring Ancient Native America: An Archaeological Guide. Taylor & Francis. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-136-78589-4.

- Wallace, Birgitta; Sollbach, Gerhard E. (18 May 2010). "Vinland-Rätsel gelöst" [Vinland Riddle Solved]. Damals (in German). Vol. 42 no. 5. pp. 47–48.

- Boissoneault, Lorraine (23 July 2015). "L'Anse Aux Meadows & the Viking Discovery of North America". JSTOR Daily.

- Wallace 2006:98–99

- Ingstad & Ingstad (2000), p. 123.

- Ingstad & Ingstad (2000), p. 141.

- "The Norse: An Arctic Mystery". The Nature of Things. CBC Television. 28 February 2015; (Episode available within Canada only)

- Weber, Bob (2018). "Ancient Arctic people may have known how to spin yarn long before Vikings arrived". Old theories being questioned in light of carbon-dated yarn samples. CBC. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

co-author Gørill Nilsen at Tromsø University in Norway came up with a way to 'shampoo' the oil out of the fibres without damaging them. Some fibres from a site on Baffin's southern coast were then subjected to the latest carbon-dating methods. The results were jaw-dropping, said Nilsen's co-author Kevin Smith of Brown University. 'They clustered into a period from about 100 AD to about 600–800 AD—roughly 1,000 years to 500 years before the Vikings ever showed up.'

- Weber, Bob (22 July 2018). "Ancient Arctic people may have known how to spin yarn long before Vikings arrived". Old theories being questioned in light of carbon-dated yarn samples. CBC. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

… Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University in Rhode Island, lead author of a recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Hayeur Smith and her colleagues were looking at scraps of yarn, perhaps used to hang amulets or decorate clothing, from ancient sites on Baffin Island and the Ungava Peninsula. The idea that you would have to learn to spin something from another culture was a bit ludicrous," she said. "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do.

- Pringle, Heather (19 October 2012). "Evidence of Viking Outpost Found in Canada". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society.

- Pringle, Heather (November 2012). "Vikings and Native Americans". National Geographic. 221 (11).

- Bird, Lindsay (12 September 2016). "On the trail of Vikings: Latest search for Norse in North America". CBC. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Parcak, Sarah; Mumford, Gregory (8 November 2017). "Point Rosee, Codroy Valley, NL (ClBu-07) 2016 Test Excavations under Archaeological Investigation Permit #16.26" (PDF). geraldpennyassociates.com, 42 pages. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

[The 2015 and 2016 excavations] found no evidence whatsoever for either a Norse presence or human activity at Point Rosee prior to the historic period. … None of the team members, including the Norse specialists, deemed this area as having any traces of human activity.

Further reading

- Campbell, Claire Elizabeth (2017). Nature, Place, and Story: Rethinking Historic Sites in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773551251.

- Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in History (third ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32755-5. ISBN 0-415-32756-3 (paperback).

- Seaver, Kirsten A. (2004). Maps, Myths, and Men: The Story of the Vinland Map. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4962-0. ISBN 0-8047-4963-9 (paperback). ISBN 978-1-13652-709-8 (ebook).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to L'Anse aux Meadows. |

- L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site by UNESCO

- The Vinland Mystery on YouTube by the National Film Board of Canada