Kassites

The Kassites (/ˈkæsaɪts/) were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC (short chronology). The endonym of the Kassites was probably Galzu,[1] although they have also been referred to by the names Kaššu, Kassi, Kasi or Kashi.

Kassite dynasty of the Babylonian Empire | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| circa 1600 BC — circa 1155 BC | |||||||||||

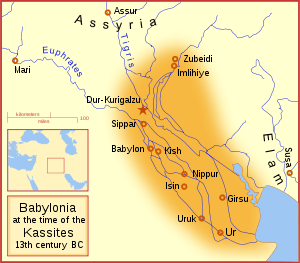

The Babylonian Empire under the Kassites, c. 13th century BC. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Dur-Kurigalzu | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Kassite language | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• ca. 1500 BC | Agum II (first) | ||||||||||

• 1157—1155 BC | Enlil-nadin-ahi (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||||

• Established | circa 1531 BC | ||||||||||

• Sack of Babylon | circa 1531 BC | ||||||||||

| circa 1158 BC | |||||||||||

• Disestablished | circa 1155 BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

They gained control of Babylonia after the Hittite sack of the city in 1595 BC (i.e. 1531 BC per the short chronology), and established a dynasty based first in Babylon and later in Dur-Kurigalzu.[2][3] The Kassites were members of a small military aristocracy but were efficient rulers and not locally unpopular,[4] and their 500-year reign laid an essential groundwork for the development of subsequent Babylonian culture.[3] The chariot and the horse, which the Kassites worshipped, first came into use in Babylonia at this time.[4]

The Kassite language has not been classified.[3] What is known is that their language was not related to either the Indo-European language group, nor to Semitic or other Afro-Asiatic languages, and is most likely to have been a language isolate although some linguists have proposed a link to the Hurro-Urartian languages of Asia Minor.[5] However, the arrival of the Kassites has been connected to the contemporary migrations of Indo-European peoples.[6][7][8][9] Several Kassite leaders and deities bore Indo-European names,[6][7][8][10][11] and it is possible that they were dominated by an Indo-European elite similar to the Mitanni, who ruled over the Hurro-Urartian-speaking Hurrians of Asia Minor.[6][7][8]

History

Late Bronze Age

Origins The original homeland of the Kassites is not well established, but appears to have been located in the Zagros Mountains, in what is now the Lorestan Province of Iran. However, the Kassites were—like the Elamites, Gutians and Manneans who preceded them—linguistically unrelated to the Iranian-speaking peoples who came to dominate the region a millennium later.[12][13] They first appeared in the annals of history in the 18th century BC when they attacked Babylonia in the 9th year of the reign of Samsu-iluna (reigned c. 1749–1712 BC), the son of Hammurabi. Samsu-iluna repelled them, as did Abi-Eshuh, but they subsequently gained control of Babylonia c. 1570 BC some 25 years after the fall of Babylon to the Hittites in c. 1595 BC, and went on to conquer the southern part of Mesopotamia, roughly corresponding to ancient Sumer and known as the Dynasty of the Sealand by c. 1520 BC. The Hittites had carried off the idol of the god Marduk, but the Kassite rulers regained possession, returned Marduk to Babylon, and made him the equal of the Kassite Shuqamuna. The circumstances of their rise to power are unknown, due to a lack of documentation from this so-called "Dark Age" period of widespread dislocation. No inscription or document in the Kassite language has been preserved, an absence that cannot be purely accidental, suggesting a severe regression of literacy in official circles. Babylon under Kassite rulers, who renamed the city Karanduniash, re-emerged as a political and military power in Mesopotamia. A newly built capital city Dur-Kurigalzu was named in honour of Kurigalzu I (ca. early 14th century BC).

Their success was built upon the relative political stability that the Kassite monarchs achieved. They ruled Babylonia practically without interruption for almost four hundred years—the longest rule by any dynasty in Babylonian history.

Formation of Kassite power

The transformation of southern Mesopotamia into a territorial state, rather than a network of allied or combative city states, made Babylonia an international power, although it was often overshadowed by its northern neighbour, Assyria and by Elam to the east. Kassite kings established trade and diplomacy with Assyria. Puzur-Ashur III of Assyria and Burna-Buriash I signed a treaty agreeing the border between the two states in the mid-16th century BC, Egypt, Elam, and the Hittites, and the Kassite royal house intermarried with their royal families. There were foreign merchants in Babylon and other cities, and Babylonian merchants were active from Egypt (a major source of Nubian gold) to Assyria and Anatolia. Kassite weights and seals, the packet-identifying and measuring tools of commerce, have been found in as far afield as Thebes in Greece, in southern Armenia, and even in the Uluburun shipwreck off the southern coast of today's Turkey.

A further treaty between Kurigalzu I and Ashur-bel-nisheshu of Assyria was agreed in the mid-15th century BC. However, Babylonia found itself under attack and domination from Assyria for much of the next few centuries after the accession of Ashur-uballit I in 1365 BC who made Assyria (along with the Hittites and Egyptians) the major power in the Near East. Babylon was sacked by the Assyrian king Ashur-uballit I (1365–1330 BC)) in the 1360s after the Kassite king in Babylon who was married to the daughter of Ashur-uballit was murdered. Ashur-uballit promptly marched into Babylonia and avenged his son-in-law, deposing the king and installing Kurigalzu II of the royal Kassite line as king there. His successor Enlil-nirari (1330–1319 BC) also attacked Babylonia and his great grandson Adad-nirari I (1307–1275 BC) annexed Babylonian territory when he became king. Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BC) not content with merely dominating Babylonia went further, conquering Babylonia, deposing Kashtiliash IV and ruling there for eight years in person from 1235 BC to 1227 BC.

Control and prestige

The Kassite kings maintained control of their realm through a network of provinces administered by governors. Almost equal with the royal cities of Babylon and Dur-Kurigalzu, the revived city of Nippur was the most important provincial center. Nippur, the formerly great city, which had been virtually abandoned c. 1730 BC, was rebuilt in the Kassite period, with temples meticulously re-built on their old foundations. In fact, under the Kassite government, the governor of Nippur, who took the Sumerian-derived title of Guennakku, ruled as a sort of secondary and lesser king. The prestige of Nippur was enough for a series of 13th-century BC Kassite kings to reassume the title 'governor of Nippur' for themselves.

Other important centers during the Kassite period were Larsa, Sippar and Susa. After the Kassite dynasty was overthrown in 1155 BC, the system of provincial administration continued and the country remained united under the succeeding rule, the Second Dynasty of Isin.

Written record

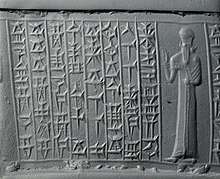

Documentation of the Kassite period depends heavily on the scattered and disarticulated tablets from Nippur, where thousands of tablets and fragments have been excavated. They include administrative and legal texts, letters, seal inscriptions, kudurrus (land grants and administrative regulations), private votive inscriptions, and even a literary text (usually identified as a fragment of a historical epic).

"Kassite rulers in Babylon were also scrupulous to follow existing forms of expression, and the public and private patterns of behavior "and even went beyond that—as zealous neophytes do, or outsiders, who take up a superior civilization—by favoring an extremely conservative attitude, at least in palace circles." (Oppenheim 1964, p. 62).

Fall of the Kassite Kings

The Elamites conquered Babylonia in the 12th century BC, thus ending the Kassite state. The last Kassite king, Enlil-nadin-ahi, was taken to Susa and imprisoned there, where he also died.

Iron Age

The Kassites did briefly regain control over Babylonia with Dynasty V (1025–1004 BC); however, they were deposed once more, this time by an Aramean dynasty.

Ethnic Kassites

Kassites survived as a distinct ethnic group in the mountains of Lorestan (Luristan) long after the Kassite state collapsed. Babylonian records describe how the Assyrian king Sennacherib on his eastern campaign of 702 BC subdued the Kassites in a battle near Hulwan, Iran.

Herodotus and other ancient Greek writers sometimes referred to the region around Susa as "Cissia", a variant of the Kassite name. However, it is not clear if Kassites were actually living in that region so late.

During the later Achaemenid period, the Kassites, referred to as "Kossaei", lived in the mountains to the east of Media and were one of several "predatory" mountain tribes that regularly extracted "gifts" from the Achaemenid Persians, according to a citation of Nearchus by Strabo (13.3.6).

As soldiers in foreign wars

But Kassites again fought on the Persian side in the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC, in which the Persian Empire fell to Alexander the Great, according to Diodorus Siculus (17.59) (who called them "Kossaei") and Curtius Rufus (4.12) (who called them "inhabitants of the Cossaean mountains"). According to Strabo's citation of Nearchus, Alexander later separately attacked the Kassites "in the winter", after which they stopped their tribute-seeking raids.

Strabo also wrote that the "Kossaei" contributed 13,000 archers to the army of Elymais in a war against Susa and Babylon. This statement is hard to understand, as Babylon had lost importance under Seleucid rule by the time Elymais emerged around 160 BC. If "Babylon" is understood to mean the Seleucids, then this battle would have occurred sometime between the emergence of Elymais and Strabo's death around 25 AD. If "Elymais" is understood to mean Elam, then the battle probably occurred in the 6th century BC. Susa was the capital of Elam and later of Elymais, so Strabo's statement implies that the Kassites intervened to support a particular group within Elam or Elymais against their own capital, which at that moment was apparently allied with or subject to Babylon or the Seleucids.

Final records

The latest evidence of Kassite culture is a reference by the 2nd-century geographer Ptolemy, who described "Kossaei" as living in the Susa region, adjacent to the "Elymeans". This could represent one of many cases where Ptolemy relied on out-of-date sources.

It is believed that the name of the Kassites is preserved in the name of the Kashgan River, in Lorestan.

Kassite dynasty of Babylon

| Ruler | Reigned: (short chronology) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agum-Kakrime | Returns Marduk statue to Babylon | ||

| Burnaburiash I | c. 1500 BC (short) | Treaty with Puzur-Ashur III of Assyria | |

| Kashtiliash III | |||

| Ulamburiash | c. 1480 BC (short) | Conquers the first Sealand Dynasty | |

| Agum III | c. 1470 BC (short) | Possible campaigns against "The Sealand" and "in Dilmun" | |

| Karaindash | c. 1410 BC (short) | Treaty with Ashur-bel-nisheshu of Assyria | |

| Kadashman-harbe I | c. 1400 BC (short) | Campaign against the Sutû | |

| Kurigalzu I | c. x-1375 BC (short) | Founder of Dur-Kurigalzu and contemporary of Thutmose IV | |

| Kadashman-Enlil I | c. 1374—1360 BC (short) | Contemporary of Amenophis III of the Egyptian Amarna letters | |

| Burnaburiash II | c. 1359—1333 BC (short) | Contemporary of Akhenaten and Ashur-uballit I | |

| Kara-hardash | c. 1333 BC (short) | Grandson of Ashur-uballit I of Assyria | |

| Nazi-Bugash or Shuzigash | c. 1333 BC (short) | Usurper “son of a nobody” | |

| Kurigalzu II | c. 1332—1308 BC (short) | Son of Burnaburiash II, Lost ? Battle of Sugagi with Enlil-nirari of Assyria | |

| Nazi-Maruttash | c. 1307—1282 BC (short) | Lost territory to Adad-nirari I of Assyria | |

| Kadashman-Turgu | c. 1281—1264 BC (short) | Contemporary of Hattusili III of the Hittites | |

| Kadashman-Enlil II | c. 1263—1255 BC (short) | Contemporary of Hattusili III of the Hittites | |

| Kudur-Enlil | c. 1254—1246 BC (short) | Time of Nippur renaissance | |

| Shagarakti-Shuriash | c. 1245—1233 BC (short) | “Non-son of Kudur-Enlil” according to Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria | |

| Kashtiliashu IV | c. 1232—1225 BC (short) | Deposed by Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria | |

| Enlil-nadin-shumi | c. 1224 BC (short) | Assyrian vassal king | |

| Kadashman-Harbe II | c. 1223 BC (short) | Assyrian vassal king | |

| Adad-shuma-iddina | c. 1222—1217 BC (short) | Assyrian vassal king | |

| Adad-shuma-usur | c. 1216—1187 BC (short) | Sender of rude letter to Aššur-nirari and Ilī-ḫaddâ, the kings of Assyria | |

| Meli-Shipak II | c. 1186—1172 BC (short) | Correspondence with Ninurta-apal-Ekur confirming foundation of Near East chronology | |

| Marduk-apla-iddina I | c. 1171—1159 BC (short) | ||

| Zababa-shuma-iddin | c. 1158 BC (short) | Defeated by Shutruk-Nahhunte of Elam | |

| Enlil-nadin-ahi | c. 1157—1155 BC (short) | Defeated by Kutir-Nahhunte II of Elam |

Culture

Social life

In spite of the fact that some of them took Babylonian names, the Kassites retained their traditional clan and tribal structure, in contrast to the smaller family unit of the Babylonians. They were proud of their affiliation with their tribal houses, rather than their own fathers, preserved their customs of fratriarchal property ownership and inheritance.[14]

Language

The Kassite language has not been classified.[3] However, several Kassite leaders bore Indo-European names, and they might have had an Indo-European elite similar to the Mitanni.[11][9] Over the centuries, however, the Kassites were absorbed into the Babylonian population. Eight among the last kings of the Kassite dynasty have Akkadian names, Kudur-Enlil's name is part Elamite and part Sumerian and Kassite princesses married into the royal family of Assyria.

Herodotus was almost certainly referring to Kassites when he described "Ethiopians [from] above Egypt" in the Persian army that invaded Greece in 492 BC.[15] Herodotus was presumably repeating an account that had used the name "Kush" (Cush), or something similar, to describe the Kassites; "Kush" was also, purely by coincidence, a name for Ethiopia. A similar confusion of Kassites with Ethiopians is evident in various ancient Greek accounts of the Trojan war hero Memnon, who was sometimes described as a "Kissian" and founder of Susa, and other times as Ethiopian. According to Herodotus, the "Asiatic Ethiopians" lived not in Kissia, but to the north, bordering on the "Paricanians" who in turn bordered on the Medes. The Kassites were not geographically linked to Kushites and Ethiopians, nor is there any documentation describing them as similar in appearance, and the Kassite language is regarded as a language isolate, utterly unrelated to any language of Ethiopia or Kush/Nubia,[16] although more recently a possible relationship to the Hurro-Urartian family of Asia Minor has been proposed.[17] However, the evidence for its genetic affiliation is meager due to the scarcity of extant texts.

According to the Encyclopædia Iranica:

There is not a single connected text in the Kassite language. The number of Kassite appellatives is restricted (slightly more than 60 vocables, mostly referring to colors, parts of the chariot, irrigation terms, plants, and titles). About 200 additional lexical elements can be gained by the analysis of the more numerous anthroponyms, toponyms, theonyms, and horse names used by the Kassites (see Balkan, 1954, passim; Jaritz, 1957 is to be used with caution). As is clear from this material, the Kassites spoke a language without a genetic relationship to any other known tongue.

Gallery

Male head from Dur-Kurigalzu, Iraq, Kassite, reign of Marduk-apla-iddina I. Iraq Museum

Male head from Dur-Kurigalzu, Iraq, Kassite, reign of Marduk-apla-iddina I. Iraq Museum Door socket from Dur-Kurigalzu, Iraq. Kassite period, 14th century BCE. Sulaymaniyah Museum

Door socket from Dur-Kurigalzu, Iraq. Kassite period, 14th century BCE. Sulaymaniyah Museum Detail, facade of Inanna's Temple at Uruk, Kassite, 15th century BCE. Iraq Museum

Detail, facade of Inanna's Temple at Uruk, Kassite, 15th century BCE. Iraq Museum Statue of a lion, Kassite, Iraq Museum

Statue of a lion, Kassite, Iraq Museum Limestone relief of a male figure from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq. Kassite. Iraq Museum

Limestone relief of a male figure from Tell al-Rimah, Iraq. Kassite. Iraq Museum Terracotta plaque of a seated goddess, from Southern Mesopotamia, Iraq. Kassite period. Ancient Orient Museum

Terracotta plaque of a seated goddess, from Southern Mesopotamia, Iraq. Kassite period. Ancient Orient Museum Duck-shaped weight mentioning the name of the priest Mashallim-Marduk, Kassite, from Babylon. Ancient Orient Museum

Duck-shaped weight mentioning the name of the priest Mashallim-Marduk, Kassite, from Babylon. Ancient Orient Museum Lapis Lazuli fragment with building inscriptions, Kassite, from Iraq. Ancient Orient Museum

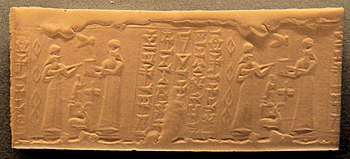

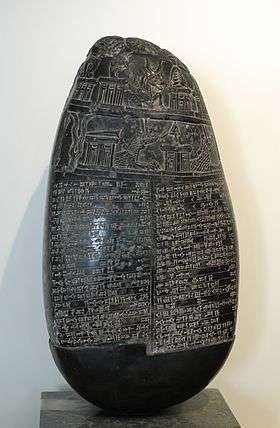

Lapis Lazuli fragment with building inscriptions, Kassite, from Iraq. Ancient Orient Museum Kudurru mentioning the name of the Kassite king Kurigalzu II, from Nippur, Iraq, Ancient Orient Museum

Kudurru mentioning the name of the Kassite king Kurigalzu II, from Nippur, Iraq, Ancient Orient Museum Babylonian cuneiform tablet with a map from Nippur, Kassite period, 1550-1450 BCE

Babylonian cuneiform tablet with a map from Nippur, Kassite period, 1550-1450 BCE Winged centaur hunting animals. Kassite period. Louvre Museum, reference AO 22355

Winged centaur hunting animals. Kassite period. Louvre Museum, reference AO 22355

See also

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Iraq |

.jpg) |

|

|

|

|

- Cities of the ancient Near East

- Early Kassite rulers

- Kassite Art

- Hittites

- Hyksos

- Kaska

- Kassite deities

- Mitanni

- Philistines

- Sea Peoples

- Short chronology timeline

References

- Trevor Bryce, 2009, The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire, Abingdon, Routledge, p. 375.

- "The Old Hittite Kingdom". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "The Kassites in Babylonia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- "Kassite (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Schneider, Thomas (2003). "Kassitisch und Hurro-Urartäisch. Ein Diskussionsbeitrag zu möglichen lexikalischen Isoglossen". Altorientalische Forschungen (in German) (30): 372–381.

- Myres, Sir John Lynton (1930). Who Were the Greeks?. University of California Press. p. 102.

Among the names of Kassite kings are some which appear to contain Indo-European elements, as though they belonged to families which had once used Indo-European speech, but had lost it as their official language, through assimilation to the people of Kassite speech whose movements they were now directing. Some Kassite deities too seem to have Indo-European names.

- MacHenry, Robert (1992). The new encyclopaedia Britannica: in 32 vol. Macropaedia, India - Ireland, Volume 21. Encyclopedia Britannica. p. 36. ISBN 0852295537.

That there was a migration of Indo-European speakers, possibly in waves, which can be dated to the 2nd millennium bc, is clear from archaeological and epigraphic evidence in western Asia. Mesopotamia witnessed the arrival, in about 1760 bc, of the Kassites, who introduced the horse and the chariot and bore such obviously Indo- European names as Surias, Indas, and Maruttas (Surya, Indra, and Marutah in Sanskrit).

- Phillips, E. D. (1963). "The Peoples of the Highland: Vanished Cultures of Luristan, Mannai and Urartu". Vanished Civilizations of the Ancient World. McGraw-Hill: 241. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

During the 2nd millennium the long process began by which Indo-European peoples from the northern steppes beyond the Caucasus established themselves about Western Asia, Iran and northern India. Their earliest pressure perhaps drove some the native peoples of the mountains to migrate or infiltrate and sometimes come as invaders into Mesopotamia and northern Syria, even in the 3rd millennium. The Indo-Europeans then drove their way through these peoples, drawing many of them in their train as subjects or allies, and appeared themselves early in the 2nd millennium as invaders and conquerors in the Near East. For the first half of the millenium the highlanders under Indo-European leadership dominated the older peoples of the plains, most of whom were Semites. The most powerful of these Indo-Europeans were the Hittites who ruled Anatolia, and later extended their dominion over northern Syria, but their connection with our three cultures is not direct, unles more Hittite influence was felt in Urartu than has so far appeared. Two other peoples are directly relevant, namely the Kassites from the Zagros mountains in the region of Luristan, and the Hurrians, who spread from regions further north, particularly from Armenia. Both were themselves native peoples of the highland, and spoke languages which were not Indo-European, but belonged to a group sometimes loosely called Caucasian, once widespread but later surviving only in the Caucasus. They were led by Indo- European aristocracies small in numbers but great in energy and achievement. They were the first to use the horse in war to draw the light chariot with spoked wheels. Indo-European names of gods at least appear among the Kassites, and of gods and rulers much more obviously among the Hurrians, in whom this element was clearly stronger. In both cases the names reveal the Indic branch of the Indo-European family, of which the main body moved through Iran to conquer northern India.

- "Iranian art and architecture". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- Piggot, Stuart (1970). Ancient Europe. Transaction Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 0202364186.

The Kassite dynasty of Mesopotamia (with Indo-European names) was established early in the second millennium B.C.

- "India: Early Vedic period". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "Lorestan". Education.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- "History of Iran". Iranologie.com. 1997-01-01. Archived from the original on 2013-02-12. Retrieved 2013-02-12.

- J. Boardman et al. (eds) Cambridge Ancient History Vol III Pt 1 (2nd Ed) 1982

- Herodotus, Book 7, Chapter 70

- see Balkan, 1954,

- Schneider, Thomas (2003). "Kassitisch und Hurro-Urartäisch. Ein Diskussionsbeitrag zu möglichen lexikalischen Isoglossen". Altorientalische Forschungen (in German) (30): 372–381.

- Land grant to Ḫunnubat-Nanaya kudurru, Sb 23, published as MDP X 87, found with Sb 22 during the French excavations at Susa.

Sources

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911.

- A. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization, 1964.

- K. Balkan, Die Sprache der Kassiten, (The Language of the Kassites), American Oriental Series, vol. 37, New Haven, Conn., 1954.

- D. T. Potts, Elamites and Kassites in the Persian Gulf, Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 111–119, (April 2006)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kassites. |

- Daniel A. Nevez, 'Provincial administration at Kassite Nippur' abstract of a dissertation gives details of Kassite Nippur and Babylonia.

- Christopher Edens, "Structure, Power and Legitimation in Kassite Babylonia"

- Richard Hooker, "The Kassites: 1530-1170 The Kassite Interregnum"

- Kassites in Encyclopaedia Britannica

- David W. Koeller, "Kassite rule in Mesopotamia"

- Kassites in Encyclopedia Iranica by Ran Zadok

- Livius.org: Kassites/Cossaeans