List of kings of Babylon

The king of Babylon (Akkadian: šar Bābili) was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th century BC to its fall in the 6th century BC. For the majority of its existence as an independent kingdom, Babylon ruled most of southern Mesopotamia, composed of the ancient regions of Sumer and Akkad. The city experienced two major periods of ascendancy, when Babylonian kings rose to dominate large parts of the Ancient Near East; the First Babylonian Empire (or Old Babylonian Empire; 1894–1595 BC according to the middle chronology) and the Second Babylonian Empire (or Neo-Babylonian Empire; 626–539 BC).

| King of Babylon | |

|---|---|

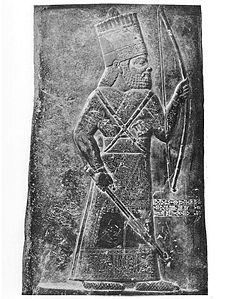

Reconstruction of a typical c. 16th/15th–10th century BC Babylonian king | |

| Details | |

| First monarch | Sumu-abum |

| Last monarch |

|

| Formation | c. 1894 BC |

| Abolition |

|

| Appointer | Divine right and the Babylonian priesthood |

The title šar Bābili was applied to Babylonian rulers relatively late, from the 8th century BC and onwards. Preceding Babylonian kings had typically used the title Viceroy of Babylon (Akkadian: šakkanakki Bābili) out of reverence for Babylon's patron deity Marduk, considered the city's formal "king". Other titles frequently used by the Babylonian monarchs included the geographical titles King of Sumer and Akkad (Akkadian: šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi) and King of Karduniash (Akkadian: šar Karduniaš), "Karduniash" being the name applied to Babylon's kingdom by the city's third dynasty (the Kassites).

Many of Babylon's kings were of foreign origin. Throughout the city's nearly two-thousand year history, it was ruled by kings of native Babylonian, Amorite, Kassite, Assyrian, Elamite, Chaldean, Persian, Hellenic and Parthian origin. A king's cultural and ethnic background does not appear to have been important for the Babylonian perception of kingship, the important matter instead being whether the king was capable of executing the duties traditionally ascribed to the Babylonian king; establishing peace and security, upholding justice, honoring civil rights, refraining from unlawful taxation, respecting religious traditions, constructing temples and providing gifts to the gods in them as well as maintaining cultic order. Babylonian revolts of independence directed against Assyrian and Persian rulers probably had little to do with said rulers not being Babylonians and more to do with the rulers rarely visiting Babylon and failing to partake in the city's rituals and traditions.

Babylon's last native king was Nabonidus, who reigned from 556 to 539 BC. Nabonidus's rule was ended through Babylon being conquered by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire. Though early Achaemenid kings continued to place importance on Babylon and continued using the title "King of Babylon", later Achaemenid rulers being ascribed the title is probably only something done by the Babylonians themselves, with the kings having abandoned it. Though it is doubtful if any later monarchs claimed the title, Babylonian scribes continued to accord it to the rulers of the empires that controlled Babylonia until the time of the Parthian Empire, when Babylon was gradually abandoned. Though Babylonia never regained indepence after the Achaemenid conquest, there were several attempts by Babylonians to drive out their foreign rulers and re-establish their kingdom, possibly as late as 336 BC under the rebel Nidin-Bel.

Titles

Throughout the city's long history, various titles were used to designate the ruler of Babylon and its kingdom, the most common[1] of which were "Viceroy/Governor of Babylon" (šakkanakki Bābili),[2] "King of Karduniash" (šar Karduniaš)[3] and "King of Sumer and Akkad" (šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi).[4] "Viceroy/Governor of Babylon" emphasizes the political dominion of the city, whereas the other two refer to southern Mesopotamia as a whole.[1] Use of one of the titles did not mean that the others could not be used simultaneously. For instance, the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III, who conquered Babylon in 729 BC, used all three.[5]

The reason why "Governor/Viceroy of Babylon" was used rather than "King of Babylon" (šar Bābili)[6] for much of the city's history was that the true king of Babylon was formally considered to be its national deity, Marduk. By being titled as šakkanakki rather than šar, the Babylonian king thus showed reverence to the city's god. This practice was ended by the Neo-Assyrian king Sennacherib, who in 705 BC took the title šar Bābili rather than šakkanakki Bābili, something which alongside various other perceived offences contributed to widespread negative reception of the king in Babylonia.[7] Sennacherib's immediate successors, including his son Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC) typically used šakkanakki Bābili,[8] though there are examples of Esarhaddon and Esarhaddon's successor Shamash-shum-ukin (r. 668–648 BC) using šar Bābili as well.[9]

"King of Babylon", rather than "Governor/Viceroy", would then be used for all following kings. It was used by the Neo-Babylonian kings,[10] and by the early Achaemenid Persian rulers.[6] The Achaemenids used the title King of Babylon and King of the Lands until it was gradually abandoned by Xerxes I in 481 BC after he had to deal with numerous Babylonian revolts.[11] The last Achaemenid king whose inscriptions use the title was Artaxerxes I, the successor of Xerxes I.[12] Later monarchs likely rarely (if at all) used the title, but the rulers of Mesopotamia continued to be accorded it for centuries by the Babylonians themselves, as late as the Parthian period. The Parthian kings were styled in inscriptions as LUGAL (the inscription of šar).[13] The standard Parthian formula, applied for the last few kings mentioned in Akkadian-language sources, was "ar-šá-kam lugal.lugal.meš" (Aršákam šar šarrāni; "Arsaces, King of Kings").[14] The final Babylonian documents that mention and name a king are the astronomical diaries LBAT 1184 and LBAT 1193,[14] written during the reign of the Parthian king Phraates IV (r. 37–2 BC), dated to 11 BC and 5 BC, respectively.[15]

The title "King of Sumer and Akkad" was introduced during the Third Dynasty of Ur, centuries before Babylon was founded, and allowed rulers to connect themselves to the culture and legacy of the Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations,[16] as well as lay claim on the political hegemony achieved during the ancient Akkadian Empire. Furthermore, the title was a geographical one in that southern Mesopotamia was typically divided into regions called Sumer (the southern regions) and Akkad (the north), meaning that "King of Sumer and Akkad" referred to rule over the entire country.[17] Alongside "King of Babylon", "King of Sumer and Akkad" was used by Babylonian monarchs until the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC.[4] The title was also used by Cyrus the Great, who conquered Babylon in 539 BC.[18][19][20]

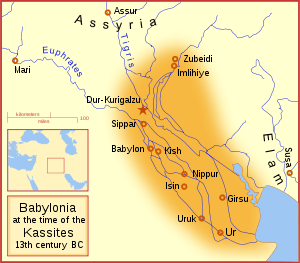

"King of Karduniash" was introduced during Babylon's third dynasty, when the city and southern Mesopotamia as a whole was ruled by the Kassites. Karduniaš was the Kassite name for the kingdom centered on Babylon and its territory.[17] The title continued being used long after the Kassites had lost control of Babylon, used for instance as late as by the native Babylonian king Nabu-shuma-ukin I (r. c. 900–888 BC)[21] and by Esarhaddon.[8]

Role and legitimacy

The Babylonian kings derived their right to rule from divine appointment by Babylon's patron deity Marduk and through consecration by the city's priests.[22] Marduk's main cult image (often conflated with the god himself), the Statue of Marduk, was prominently used in the coronation rituals for the kings, who received their crowns "out of the hands" of Marduk during the New Year's festival, symbolizing them being bestowed with kingship by the deity.[11][n 1] The king's rule and his role as Marduk's vassal on Earth were reaffirmed annually at this time of year, when the king entered the Esagila alone on the fifth day of the New Year's Festival each year and met with the chief priest. The chief priest removed the regalia from the king, slapped him across the face and made him kneel before Marduk's statue. The king would then tell the statue that he had not oppressed his people and that he had maintained order throughout the year, whereafter the chief priest would reply (on behalf of Marduk) that the king could continue to enjoy divine support for his rule, returning the royal regalia.[25] Through being a patron of Babylon's temples, the king extended his generosity towards the Mesopotamian gods, who in turn empowered his rule and lent him their authority.[22]

Babylonian kings were expected to establish peace and security, uphold justice, honor civil rights, refrain from unlawful taxation, respect religious traditions and maintain cultic order. None of the king's responsibilities and duties required him to be ethnically or even culturally Babylonian; any foreigner sufficiently familiar with the royal customs of Babylonia could adopt the title,[22] though they might then require the assistance of the native priesthood and the native scribes. Ethnicity and culture does not appear to have been important in the Babylonian perception of kingship; many foreign kings enjoyed support from the Babylonians and several native kings were despised.[26] That the rule of some foreign kings was not supported by the Babylonians probably has little to do with their ethnic or cultural background.[27] What was always more important was whether the ruler was capable of executing the duties of the Babylonian king properly, in line with established Babylonian tradition.[28] The frequent Babylonian revolts against foreign rulers, such as the Assyrians and the Persians, can most likely be attributed to the Assyrian and Persian kings being perceived as failing in their duties as Babylonian monarchs. Since their capitals were elsewhere, they did not regularly partake in the city's rituals (meaning that they could not be celebrated in the same way that they traditionally were) and they rarely performed their traditional duties to the Babylonian cults through constructing temples and presenting cultic gifts to the city's gods. This failure might have been interpreted as the kings thus not having the necessary divine endorsement to be considered true kings of Babylon.[29]

Amorite dynasty (c. 1894–1595 BC)

The regnal dates below (and for the rest of the list, where applicable) follow Chen (2020),[30] which in turn follows the middle chronology of Mesopotamian history, the chronology most commonly encountered in literature, including most current textbooks on the archaeology and history of the Ancient Near East.[31][32][33]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Sumu-abum Šumu-abum |

c. 1894 – 1881 BC | Babylon's first king; liberated the city from the control of the city-state Kazallu | [30] |

| — | Sumu-la-El Šumu-la-El |

c. 1880 – 1845 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Sabium Sabūm |

c. 1844 – 1831 BC | Son of Sumu-la-El | [30] |

| — | Apil-Sin Apil-Sîn |

c. 1830 – 1813 BC | Son of Sabium | [30] |

| — | Sin-Muballit Sîn-Muballit |

c. 1812 – 1793 BC | Son of Apil-Sin | [30] |

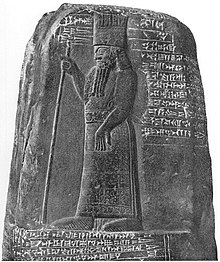

|

Hammurabi Ḫammu-rāpi |

c. 1792 – 1750 BC | Son of Sin-Muballit | [30] |

| — | Samsu-iluna Šamšu-iluna |

c. 1749 – 1712 BC | Son of Hammurabi | [30] |

| — | Abishi Abiši |

c. 1711 – 1684 BC | Son of Samsu-iluna | [30] |

| — | Ammi-Ditana Ammi-ditāna |

c. 1683 – 1647 BC | Son of Abishi | [30] |

| — | Ammi-Saduqa Ammi-Saduqa |

c. 1646 – 1626 BC | Son of Ammi-Ditana | [30] |

| — | Samsu-Ditana Šamšu-ditāna |

c. 1625 – 1595 BC | Son of Ammi-Saduqa | [30] |

Interim kings

Samsu-Ditana's reign ended (according to the middle chronology) in 1595 BC with the sack and destruction of Babylon by the Hittites. Babylon and its kingdom would not be firmly re-established until the reign of the Kassite king Agum II.[34] Babylonian king lists consider the kings listed in this section as kings of Babylon between the Amorite dynasty and the Kassite dynasty, though most of them are unlikely to have ruled Babylon itself and the three dynasties likely overlapped significantly.[35] Precise dates for the reigns of these kings are not known.[30]

First Sealand dynasty

The First Sealand dynasty might only have ruled Babylonia itself for the briefest of periods, being based in formerly Sumerian regions south of it. Nevertheless, it is often traditionally numbered the Second Dynasty of Babylon. Little is known of these rulers. They were counted as kings of Babylon in later king lists, succeeding the Amorite dynasty despite overlapping reigns.[35]

- Ilum-ma-ili (Ilum-ma-ilī), 60 years.[30]

- Itti-ili-nibi (Itti-ili-nībī), 56(?) years.[30]

- Damqi-ilishu (Damqi-ilišu), 26(?) years.[30]

- Ishkibal (Iškibal), 15 years.[30]

- Shushushi (Šušši), 24 years.[30]

- Gulkishar (Gulkišar), 55 years.[30]

- mDIŠ+U-EN (mDIŠ-U-EN; reading unknown), 12 years.[30]

- Peshgaldaramesh (Pešgaldarameš), son of Gulkishar, 50 years.[30]

- Ayadaragalama (Ayadaragalama), son of Peshgaldaramesh, 28 years.[30]

- Akurduana (Akurduana), 26 years.[30]

- Melamkurkurra (Melamkurkurra), 7 years.[30]

- Ea-gamil (Ea-gamil), 9 years.[30]

Early Kassite rulers

These kings also did not actually rule Babylon, but succeeding Kassite kings did. Little is known of these rulers. They were counted as kings of Babylon in later king lists, succeeding the Sealand dynasty despite overlapping reigns.[35]

- Gandash (Gandaš), 26 years.[30]

- Agum I Mahru (Agum Maḫrû), son of Gandash, 22 years.[30]

- Kashtiliash I (Kaštiliašu), son of Agum I, 22 years.[30]

- Abi-Rattash (Abi-Rattaš or Uššiašu), son of Kashtiliash I, 8(?) years.[30]

- Kashtiliash II (Kaštiliašu).[30]

- Urzigurumash (Ur-zigurumaš or Tazzigurumaš).[30]

- Hurbazum (Ḫurbazum or Ḫarba-Šipak).[30]

- Shipta'ulzi (Šipta’ulzi or Tiptakzi).[30]

Kassite dynasty (c. 16th century BC – 1155 BC)

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Agum II Kakrime Agum-Kakrime |

Uncertain | Re-established Babylon; son of Urzigurumash | [30] |

| — | Burnaburiash I Burna-Buriaš |

Uncertain | Son of Agum II | [30] |

| — | Kashtiliash III Kaštiliašu |

Uncertain | Son of Burnaburiash I | [30] |

| — | Ulamburiash Ulam-Buriaš |

Uncertain | Son of Burnaburiash I | [30] |

| — | Agum III Agum |

Uncertain | Son of Kashtiliash III | [30] |

| — | Karaindash Karaindaš |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Kadashman-harbe I Kadašman-Ḫarbe |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Kurigalzu I Kuri-Galzu |

Uncertain | Son of Kadashman-harbe I | [30] |

| Kadashman-Enlil I Kadašman-Enlil |

c. 1374 – 1360 BC | Son of Kurigalzu I | [30] | |

| — | Burnaburiash II Burna-Buriaš |

c. 1359 – 1333 BC | Son of Kadashman-Enlil I (?) | [30] |

| — | Karahardash Kara-ḫardaš |

c. 1333 BC | Son of Burnaburiash II | [30] |

| — | Nazibugash Nazi-Bugaš or Šuzigaš |

c. 1333 BC | Unrelated to other kings; usurped the throne from Karahardash | [30] |

| Kurigalzu II Kuri-Galzu |

c. 1332 – 1308 BC | Son of Burnaburiash II; appointed by the Assyrian king Ashur-uballit I | [30] | |

| — | Nazimaruttash Nazi-Maruttaš |

c. 1307 – 1282 BC | Son of Kurigalzu II | [30] |

| — | Kadashman-Turgu Kadašman-Turgu |

c. 1281 – 1264 BC | Son of Nazi-Maruttash | [30] |

| — | Kadashman-Enlil II Kadašman-Enlil |

c. 1263 – 1255 BC | Son of Kadashman-Turgu | [30] |

| — | Kudur-Enlil Kudur-Enlil |

c. 1254 – 1246 BC | Son of Kadashman-Enlil II | [30] |

| — | Shagarakti-Shuriash Šagarakti-Šuriaš |

c. 1245 – 1233 BC | Son of Kudur-Enlil | [30] |

| — | Kashtiliash IV Kaštiliašu |

c. 1232 – 1225 BC | Son of Shagarakti-Shuriash | [30] |

| — | Enlil-nadin-shumi Enlil-nādin-šumi |

c. 1224 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Kadashman-harbe II Kadašman-Ḫarbe |

c. 1223 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Adad-shuma-iddina Adad-šuma-iddina |

c. 1222 – 1217 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Adad-shuma-usur Adad-šuma-uṣur |

c. 1216 – 1187 BC | Descendant (son?) of Kashtiliash IV | [30] |

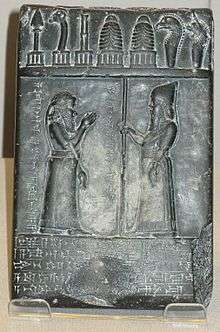

|

Meli-Shipak Meli-Šipak or Melišiḫu |

c. 1186 – 1172 BC | Son of Adad-shuma-usur | [30] |

|

Marduk-apla-iddina I Marduk-apla-iddina |

c. 1171 – 1159 BC | Son of Meli-Shipak | [30] |

|

Zababa-shuma-iddin Zababa-šuma-iddina |

c. 1158 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Enlil-nadin-ahi Enlil-nādin-aḫe or Enlil-šuma-uṣur |

c. 1157 – 1155 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

Second dynasty of Isin (c. 1157–1026 BC)

Named in reference to the ancient Sumerian (First) Dynasty of Isin. Contemporary Babylonian documents refer to this dynasty as BALA PA.ŠE, a paronomasia (play on words) on the term išinnu ("stalk", written as PA.ŠE), interpreted by some as an apparent reference to the city Isin.[36]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Marduk-kabit-ahheshu Marduk-kabit-aḫḫēšu |

c. 1157 – 1140 BC | Unclear succession; early reign overlaps with Enlil-nadin-ahi's reign | [30] |

| — | Itti-Marduk-balatu Itti-Marduk-balāṭu |

c. 1139 – 1132 BC | Son of Marduk-kabit-ahheshu | [30] |

| — | Ninurta-nadin-shumi Ninurta-nādin-šumi |

c. 1131 – 1126 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

|

Nebuchadnezzar I Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

c. 1125 – 1104 BC | Son of Ninurta-nadin-shumi | [30] |

| — | Enlil-nadin-apli Enlil-nādin-apli |

c. 1103 – 1100 BC | Son of Nebuchadnezzar I | [30] |

|

Marduk-nadin-ahhe Marduk-nādin-aḫḫē |

c. 1099 – 1082 BC | Son of Ninurta-nadin-shumi; usurped the throne from Enlil-nadin-apli | [30] |

| — | Marduk-shapik-zeri Marduk-šāpik-zēri |

c. 1081 – 1069 BC | Possibly son of either Marduk-nadin-ahhe or Ninurta-nadin-shumi | [30] |

| — | Adad-apla-iddina Adad-apla-iddina |

c. 1068 – 1047 BC | Appointed by the Assyrian king Ashur-bel-kala | [30] |

| — | Marduk-ahhe-eriba Marduk-aḫḫē-erība |

c. 1046 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Marduk-zer-X Marduk-zer-X |

c. 1045 – 1034 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Nabu-shum-libur Nabû-šumu-libūr |

c. 1033 – 1026 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

Second Sealand dynasty (c. 1025–1005 BC)

Evidence that these kings were Kassites, a common assertion, is somewhat lacking.[37]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Simbar-shipak Simbar-Šipak |

c. 1025 – 1008 BC | Usurped the throne from Nabu-shum-libur | [30] |

| — | Ea-mukin-zeri Ea-mukin-zēri |

c. 1008 BC | Usurped the throne from Simpar-shipak | [30] |

| — | Kashshu-nadin-ahi Kaššu-nādin-aḫi |

c. 1007 – 1005 BC | Usurped the throne from Ea-mukin-zeri | [30] |

Bazi dynasty (c. 1004–985 BC)

The Bazi (or Bīt-Bazi) dynasty was a minor Kassite clan. They ruled Babylonia from the city Kar-Marduk, an otherwise unknown location which might have been better protected against raids from nomadic groups than Babylon itself.[38]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Eulmash-shakin-shumi Eulmaš-šākin-šumi |

c. 1004 – 988 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Ninurta-kudurri-usur I Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur |

c. 987 – 985 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Shirikti-shuqamuna Širikti-šuqamuna |

c. 985 BC | Brother of Ninurta-kudurri-usur I | [30] |

Elamite dynasty (c. 984–979 BC)

The Elamite dynasty only contains a single king, Mar-biti-apla-usur.[30]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Mar-biti-apla-usur Mār-bīti-apla-uṣur |

c. 984 – 979 BC | Described as having Elamite ancestry; unclear succession | [30] |

Uncertain/mixed dynasties (c. 978 – 770 BC)

Sometimes considered part of the subsequent Dynasty of E.[39]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nabu-mukin-apli Nabû-mukin-apli |

c. 978 – 943 BC | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Ninurta-kudurri-usur II Ninurta-kudurrῑ-uṣur |

c. 943 BC | Son of Nabu-mukin-apli | [30] |

| — | Mar-biti-ahhe-iddina Mār-bῑti-aḫḫē-idinna |

Uncertain | Son of Nabu-mukin-apli | [30] |

| — | Shamash-mudammiq Šamaš-mudammiq |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Nabu-shuma-ukin I Nabû-šuma-ukin |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

|

Nabu-apla-iddina Nabû-apla-iddina |

Uncertain, 33 years? | Son of Nabu-shuma-ukin I | [30] |

|

Marduk-zakir-shumi I Marduk-zâkir-šumi |

Uncertain, 27 years? | Son of Nabu-apla-iddina | [30] |

| — | Marduk-balassu-iqbi Marduk-balāssu-iqbi |

Uncertain | Son of Marduk-zakir-shumi I | [30] |

| — | Baba-aha-iddina Bāba-aḫa-iddina |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

| Interregnum: Babylon experiences a brief interregnum following the end of Baba-aha-iddina's reign. Five consecutive kings, whose names are not recorded, rule briefly during this time.[30] | ||||

| — | Ninurta-apla-X Ninurta-apla-X |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Marduk-bel-zeri Marduk-bēl-zēri |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Marduk-apla-usur Marduk-apla-uṣur |

Uncertain | Unclear succession | [30] |

Dynasty of E (c. 770–732 BC)

The Dynasty of E contains five kings, most of them seemingly unrelated, from Eriba-Marduk to Nabu-shuma-ukin II.[30] Some reconstructions of the line of Babylonian kings consider the entire period from 979 to 732 BC to be the Dynasty of E, including the kings of uncertain/mixed dynasties above.[39]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Eriba-Marduk Erība-Marduk |

c. 770 – 760 BC | A Chaldean chief; unclear succession | [30][40] |

| — | Nabu-shuma-ishkun Nabû-šuma-iškun |

c. 760 – 748 BC | A Chaldean chief; unclear succession | [30] |

| — | Nabonassar Nabû-nāṣir |

748 – 734 BC | A Native Babylonian; usurped the throne from Nabu-shuma-ishkun | [30] |

| — | Nabu-nadin-zeri Nabû-nādin-zēri |

734 – 732 BC | Son of Nabonassar | [30] |

| — | Nabu-shuma-ukin II Nabû-šuma-ukin |

732 BC | A Chaldean chief; usurped the throne from Nabu-nadin-zeri | [30] |

Shapi dynasty (732–729 BC)

The brief Shapi dynasty contains only a single king, immediately preceding the Assyrian conquest of Babylon.[30] The sole king of the dynasty, Nabu-mukin-zeri, is sometimes considered part of the subsequent Assyrian dynasty instead (then numbered as Babylon's ninth or tenth dynasty).[39]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Nabu-mukin-zeri Nabû-mukin-zēri |

732 – 729 BC | A Chaldean chief; usurped the throne from Nabu-shuma-ukin II | [30] |

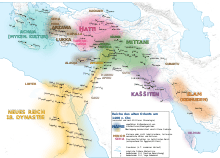

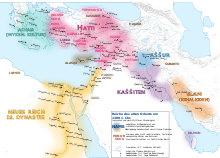

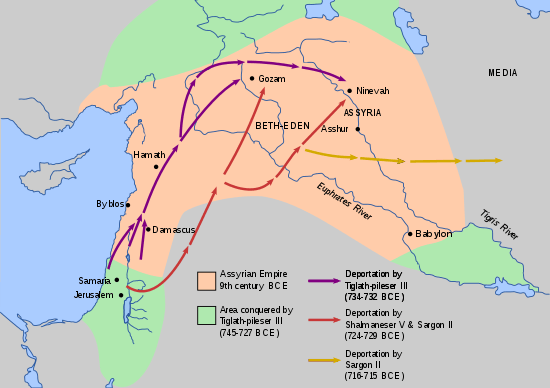

Assyrian dynasty (729–626 BC)

The Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III conquered Babylonia in 729 BC.[41] From his rule and onwards, most of the Assyrian kings were also titled as Kings of Babylon, ruling both Assyria and Babylonia in something akin to a personal union.[42]

Vassal kings, sometimes appointed instead of the Assyrian king ruling Babylonia directly, are indicated with darker grey background color. Native Babylonians who rebelled against the ruling dynasty of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and attempted to restore Babylonia's independence are indicated with beige background color.

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tiglath-Pileser (Tiglath-Pileser III) Tukultī-apil-Ešarra |

729 – 727 BC | King of the Neo-Assyrian Empire; conquered Babylon | [30] |

|

Shalmaneser (Shalmaneser V) Šulmanu-ašaridu |

727 – 722 BC | Son of Tiglath-Pileser III | [30] |

|

Marduk-apla-iddina II Marduk-apla-iddina (first reign) |

722 – 710 BC | Native Babylonian rebel; seized power in Babylonia after Shalmaneser V's death | [30] |

.jpg) |

Sargon (Sargon II) Šarru-kīn |

710 – 705 BC | Claimed to be the son of Tiglath-Pileser III; usurped the throne from Shalmaneser V, conquered Babylon in 710 BC | [30] |

|

Sennacherib Sîn-ahhe-erība |

705 – 703 BC | Son of Sargon II | [30] |

| — | Marduk-zakir-shumi II Marduk-zâkir-šumi |

703 BC | Native Babylonian rebel | [30] |

|

Marduk-apla-iddina II Marduk-apla-iddina (second reign) |

703 BC | Native Babylonian rebel, previously king 722–710 BC; usurped the throne from Marduk-zakir-shumi II | [30] |

| — | Bel-ibni Bel-ibni |

703 – 700 BC | Vassal king appointed by Sennacherib | [30] |

| — | Ashur-nadin-shumi Aššur-nādin-šumi |

700 – 694 BC | Vassal king appointed by Sennacherib; son of Sennacherib | [30] |

| — | Nergal-ushezib Nergal-ušezib |

694 – 693 BC | Native Babylonian rebel | [30] |

| — | Mushezib-Marduk Mušezib-Marduk |

693 – 689 BC | Native Babylonian rebel | [30] |

| Interregnum 689 – 680 BC: Sennacherib destroyed Babylon in 689 BC, hoping to destroy Babylonia as a political entity after its many rebellions against his rule.[43] The city's reconstruction was announced by his son and successor Esarhaddon in 680 BC.[44] Sennacherib is sometimes listed as Babylon's king during this period.[30] | ||||

|

Esarhaddon Aššur-aḫa-iddina |

680 – 669 BC | Son and successor of Sennacherib in Assyria; rebuilt Babylon | [30] |

|

Shamash-shum-ukin Šamaš-šuma-ukin |

668 – 648 BC | Vassal king under Esarhaddon's successor Ashurbanipal; brother of Ashurbanipal and son of Esarhaddon | [30] |

| — | Kandalanu Kandalānu |

648 – 627 BC | Vassal king appointed by Ashurbanipal | [30] |

| Interregnum 627 – 626 BC: Rule in Assyria was contested between Sinsharishkun and the usurper Sin-shumu-lishir and though both briefly controlled Babylon, neither used the title "King of Babylon", instead using only "King of Assyria".[45] Sinsharishkun and Sin-shumu-lishir are sometimes considered to be the Kings of Babylon 627–626 BC in modern scholarship.[30] | ||||

Neo-Babylonian dynasty (626–539 BC)

The rebel Nabopolassar, proclaimed as Babylon's king in 626 BC, successfully drove out the Assyrians from southern Mesopotamia and had united and consolidated all of Babylonia under his rule by 620 BC, founding the Neo-Babylonian Empire.[46] The Neo-Babylonian (or Chaldean)[30] dynasty was Babylonia's last dynasty of native Mesopotamian monarchs and the fall of their empire in 539 BC marked the end of Babylonia as an independent kingdom.[47]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Nabopolassar Nabû-apla-uṣur |

626 – 605 BC | Native Babylonian rebel; successfully drove out the Assyrians and re-established Babylonia as an independent kingdom | [30] |

|

Nebuchadnezzar II Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

605 – 562 BC | Son of Nabopolassar | [30] |

| — | Amel-Marduk Amēl-Marduk |

562 – 560 BC | Son of Nebuchadnezzar II | [30] |

| — | Neriglissar Nergal-šar-uṣur |

560 – 556 BC | Son-in-law or brother-in-law of Amel-Marduk; usurped the throne | [30][48] |

| — | Labashi-Marduk Labaši-Marduk |

556 BC | Son of Neriglissar | [30] |

|

Nabonidus Nabû-naʾid |

556 – 539 BC | Possibly son-in-law of Nebuchadnezzar II (or unrelated); usurped the throne from Labashi-Marduk | [30][48] |

Post-Neo-Babylonian kings

Achaemenid dynasty (539–331 BC)

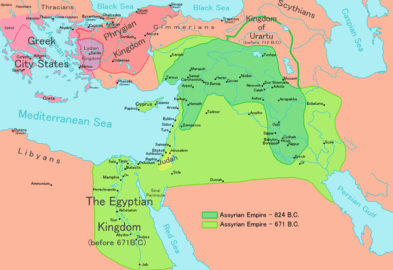

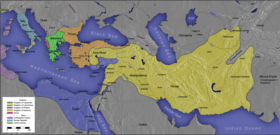

_Empire_-_Circa_480BC.png)

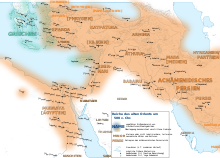

In 539, Cyrus the Great of the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered Babylon, which would never again successfully regain independence. The Babylonians had resented their last native king, Nabonidus, over his religious practices and some of his political choices and Cyrus could thus claim to be the legitimate successor of the ancient Babylonian kings and the avenger of Baylon's national deity, Marduk.[49] The early Achaemenid rulers had great respect for Babylonia, regarding the region as a separate entity or kingdom united with their own kingdom in something akin to a personal union.[11] Despite this, the native Babylonians grew to resent their foreign rulers, as they had with the Assyrians earlier, and rebelled several times. The Achaemenid kings continued to use the title "King of Babylon" alongside their other royal titles until the reign of Xerxes I, who dropped the title in 481 BC, divided the previously large Babylonian satrapy and desecrated Babylon after having had to put down a Babylonian revolt.[11]

In the king lists of the Babylonians, the Achaemenid kings continued to be recognized as Kings of Babylon until the end of the Achaemenid Empire. The Akkadian (Babylonian) names of the monarchs listed here generally follow the renderings of the names of these monarchs in the Uruk King List (also known as "King List 5") and the Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period (also known as BKLHP or “King List 6”).[50][51] These lists records rulers, identifying them as "Kings of Babylon".[52]

Native Babylonians who rebelled against the Achaemenids and attempted to restore Babylonia's independence are indicated with beige background color. Vassal kings are indicated with darker grey background color.

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cyrus the Great (Cyrus II) Kuraš |

539 – 530 BC | King of the Achaemenid Empire; conquered Babylon | [50] |

| — | Ugbaru Ugbaru |

538 BC | Possibly a vassal king appointed by Cyrus; probably a governor of the city, evidence that there was a vassal king is scant but includes Cyrus not formally assuming the title King of Babylon until 538 BC | [53] |

|

Cambyses (Cambyses II) Kambuzīa |

538 BC, 530 – 522 BC | Son of Cyrus; briefly vassal king under (or co-ruler with) his father in 538 BC as King of Babylon before being dismissed; king again upon Cyrus's death in 530 BC | [50][54][55] |

|

Bardiya Barzia |

522 BC | Son of Cyrus or possibly an impostor | [51] |

|

Nebuchadnezzar III Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

522 BC | Native Babylonian rebel; claimed to be a son of Nabonidus, his revolt against Persian rule lasted from October to December 522 BC | [56] |

| Darius I the Great Dariamuš |

522 – 486 BC | Son of Hystaspes, a third cousin of Cyrus; usurped the throne from Bardiya | [50] | |

|

Nebuchadnezzar IV Nabû-kudurri-uṣur |

521 BC | Babylonian rebel of Armenian descent; claimed to be a son of Nabonidus, his revolt lasted from 25 August to 27 November 521 BC | [56] |

|

Xerxes I the Great Aḥšiaršu |

486 – 465 BC | Son of Darius I | [11] |

| — | Bel-shimanni Bêl-šimânni |

484 BC | Native Babylonian rebel; rebelled in the summer of 484 BC, ally or rival of Shamash-eriba | [57] |

| — | Shamash-eriba Šamaš-eriba |

484 BC | Native Babylonian rebel; rebelled in the summer of 484 BC, ally or rival of Bel-shimanni | [57] |

|

Artaxerxes I Artakšatsu |

465 – 424 BC | Son of Xerxes I | [11][51] |

|

Xerxes II Aḥšiaršu |

424 BC | Son of Artaxerxes I | [51] |

| — | Sogdianus Sogdianu |

424 – 423 BC | Son of Artaxerxes I; usurped the throne from Xerxes II | [51] |

|

Darius II Dariamuš |

423 – 404 BC | Son of Artaxerxes I; usurped the throne from Sogdianus | [51] |

|

Artaxerxes II Artakšatsu |

404 – 358 BC | Son of Darius II | [51] |

|

Artaxerxes III Artakšatsu |

358 – 338 BC | Son of Artaxerxes II | [51] |

|

Artaxerxes IV Artakšatsu |

338 – 336 BC | Son of Artaxerxes III | [51] |

| — | Nidin-Bel Nidin-Bêl |

336 BC or 336 – 335 BC | Only mentioned in the Uruk King List; either a scribal error or a native Babylonian rebel who led a brief revolt | [50] |

|

Darius III Dariamuš |

336/335 – 331 BC | Great-grandson of Darius II; usurped the throne from Artaxerxes IV | [50] |

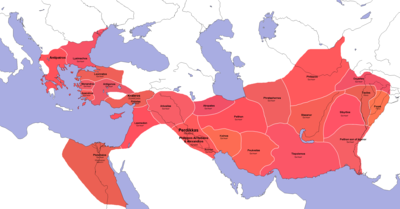

Argead dynasty (331–309 BC)

Though they probably did not use the title themselves, Babylonian king lists continue to consider the monarchs of the Hellenistic Argead dynasty, which conquered Babylonia and the rest of the Persian Empire under Alexander the Great in 331 BC, as Kings of Babylon. The Akkadian (Babylonian) names of the monarchs listed here generally follow how their names are rendered in these lists.[50][51][52]

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Alexander I the Great (Alexander III) Aliksāndar |

331 – 323 BC | King of Macedon; conquered the Achaemenid Empire | [50] |

|

Philip Arrhidaeus (Philip III) Pīlipsu |

323 – 317 BC | Brother of Alexander the Great | [50] |

|

Alexander II (Alexander IV) Aliksāndarusu |

323 – 309 BC | Son of Alexander the Great | [52] |

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Antigonus Monophthalmus (Antigonus I) Antigūnusu |

317 – 311 BC | Mentioned in some king lists; Babylonian sources suggest that the Babylonians considered Antigonus's rule illegal and that he should have accepted the sovereignty of Alexander the Great's son | [50][52] |

Seleucid dynasty (311–141 BC)

Babylonian king lists continue to consider the monarchs of the Hellenistic Seleucid dynasty, which succeeded the Argeads in Mesopotamia and Persia, as Kings of Babylon. The Akkadian (Babylonian) names of the monarchs listed here generally follow how their names are rendered in these lists.[50][52] The Antiochus Cylinder of Antiochus I (r. 271–261 BC) is the last known example of an ancient Akkadian royal titulary and it accords him several traditional Mesopotamian titles, such as King of Babylon and King of the Universe.[58]

Rebel leaders (though none were native Babylonians) and local rulers/usurpers who seized the city and were recognized as Kings of Babylon by the Babylonians are marked with light blue color.

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seleucus I Nicator Siluku |

311 – 281 BC | General (Diadochus) of Alexander the Great; seized Babylonia and much of Alexander's former eastern lands after Alexander's death, Seleucus did not proclaim himself king until 305 BC but Babylonian sources consider him as such from 311 BC onwards | [50] | |

|

Antiochus I Soter Anti'ukusu |

281 – 261 BC | Son of Seleucus I | [50] |

|

Antiochus II Theos Anti'ukusu |

261 – 246 BC | Son of Antiochus I | [50] |

%2C_Antioch_mint.jpg) |

Seleucus II Callinicus Siluku |

246 – 225 BC | Son of Antiochus II | [50] |

|

Seleucus III Ceraunus Siluku |

225 – 223 BC | Son of Seleucus II | [52] |

%2C_late_1st_century_BC%E2%80%93early_1st_century_AD%2C_Louvre_Museum_(7462828632).jpg) |

Antiochus III the Great Anti'ukusu |

222 – 187 BC | Son of Seleucus II | [52] |

|

Seleucus IV Philopator Siluku |

187 – 175 BC | Son of Antiochus III | [52] |

|

Antiochus IV Epiphanes Anti'ukusu |

175 – 164 BC | Son of Antiochus III | [52] |

|

Antiochus V Eupator Anti'ukusu |

164 – 161 BC | Son of Antiochus IV | [59] |

|

Demetrius I Soter Demeṭri |

161 – 150 BC | Son of Seleucus IV | [52] |

|

Timarchus Timarkusu |

161 – 160 BC | Satrap of Media; rebelled against Demetrius I, seized Babylon and was briefly recognized there as king | [60] |

|

Alexander III Balas (Alexander I) Aliksāndar |

150 – 145 BC | Claimed to be the son of Antiochus IV; usurped the throne from Demetrius I | [61] |

%2C_Ptolemais_in_Phoenicia_mint.jpg) |

Demetrius II Nicator Demeṭri |

145 – 141 BC | Son of Demetrius I; usurped the throne from Alexander Balas | [52] |

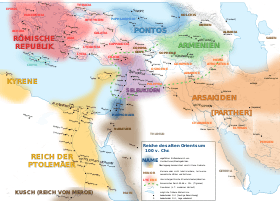

Arsacid dynasty (141 – c. 2 BC)

Babylon and the rest of Mesopotamia was lost by the Seleucids to the Parthian Empire in 141 BC. There are no Babylonian king lists which record any ruler after the Seleucids as a King of Babylon.[52] King List 6 ends, after Demetrius II, with a passage referencing "Arsaces the king", indicating that the list was created in the early years of Parthian rule in Mesopotamia (Arsaces being the regnal name used by all Parthian kings). Because the list is so fragmentary, it is unclear if this Arsaces was formally considered a King of Babylon (as the Persian and Hellenic rulers had been) by the list's author.[62] Under the Parthians, Babylon was gradually abandoned as a major urban center and the old Akkadian culture diminished.[63] Critically, the nearby and newer cities of Seleucia and later Ctesiphon overshadowed Babylon and became the imperial capitals of the region.[64] In the first century or so of Parthian rule, Babylon continued to be somewhat important[63] and documents from this time suggest a continued recognition of at least the early Parthian kings as Babylonian monarchs.[65] The few Babylonian documents that survive from the Parthian era suggest a growing sense of alarm and alienation among the last few Babylonians as the Parthian kings were mostly absent from the city and the Babylonian culture slowly slipped away.[66]

When exactly Babylon was abandoned is unclear. Roman author Pliny the Elder wrote in 50 AD that proximity to Seleucia had turned Babylon into a "barren waste" and during their campaigns in the east, Roman emperors Trajan (in 115 AD) and Septimius Severus (in 199 AD) supposedly found the city destroyed and deserted. Archaeological evidence and the writings of Abba Arikha (c. 219 AD) indicate that at least the temples of Babylon were still active in the early 3rd century.[64] Religious reforms in the early Sasanian Empire c. 230 AD would have decisively wiped out the last remnants of the old Babylonian culture, if it still existed at that point.[67]

Rebel leaders (though none were native Babylonians) and local rulers/usurpers who seized the city and were recognized as Kings of Babylon by the Babylonians are marked with light blue color. Seleucid rulers (who briefly regained Babylon) are indicated with pink color.

| Image | Name | Reign | Succession & notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mithridates I the Great Aršákā |

141 – 132 BC | King of the Parthian Empire; conquered Babylon and the rest of Mesopotamia | [68] |

%2C_Seleucia_mint.jpg) |

Phraates I (Phraates II) Aršákā |

132 – 130 BC | Son of Mithridates I | [69][70] |

|

Antiochus VI Sidetes (Antiochus VII) Anti'ukusu |

130 – 129 BC | Seleucid king; restored Seleucid control of Babylonia in 130 BC | [71] |

%2C_Seleucia_mint.jpg) |

Artabanus (Artabanus I) Aršákā and Ártabana |

129 – 124 BC | Brother of Mithridates I; Babylonian documents suggest that the Parthians were recognized as kings again in 129 BC | [71][72][73] |

|

Hyspaosines Aspāsinē |

127 BC | Originally a seleucid satrap and then King of Characene; briefly captured Babylon in 127 BC and was recognized by the Babylonians as their king for a few months | [72] |

%2C_Ecbatana_mint.jpg) |

Mithridates II the Great Aršákā |

124 – 91 BC | Son of Artabanus | [74] |

%2C_Ectbatana_mint.jpg) |

Gotarzes (Gotarzes I) Aršákā and Gutárzā |

91 – 80 BC[n 2] | Son of Mithridates II | [76][77] |

|

Orodes I Aršákā and Úrudā |

80 – 75 BC | Son of Gotarzes | [78] |

| — | Arsaces (Arsaces XVI) Aršákā |

75 – 67 BC | Obscure Parthian king attested by some sources; Orodes I's more known successor, Sinatruces, is not mentioned in any Babylonian sources, suggesting he never ruled the city | [79] |

|

Phraates II (Phraates III) Aršákám |

67 – 57 BC | Son of Sinatruces; captured Babylon | [80] |

.jpg) |

Mithridates III (Mithridates IV) Aršákám |

57 BC, 55–54 BC | Son of Phraates III; lost the throne to Orodes II shortly after gaining it, retook Babylon and the rest of Mesopotamia briefly 55–54 BC | [81] |

_mint.jpg) |

Orodes II Aršákám |

57–55 BC, 54–37 BC | Son of Phraates III; contended with his brother Mithridates in the early years of his reign | [81] |

|

Phraates III (Phraates IV) Aršákám |

37 – 2 BC | Son of Orodes II; final ruler attested as king in Babylonian sources (in an astronomical diary from 5 BC)[n 3] | [14][15] |

Notes

- The eventual fate of the Statue of Marduk is uncertain, it was supposedly removed from Babylon by Achaemenid king Xerxes I in 481 BC, whereafter it might have been destroyed.[23][24]

- Some historians place an additional Parthian king, Mithridates III of Parthia between Gotarzes I and Orodes I, reigning c. 87–80 BC. Babylonian documents only corroborate the rule of Gotarzes I and Orodes I.[75]

- There are a handful of later cuneiform tablets, but none explicitly name a king. The latest datable tablet is W22340a, dated to 79/80 AD (from the reign of Parthian king Artabanus III). W22340a preserves the word LUGAL (king) but it is too fragmentary to firmly indicate that the intended king is Artabanus III.[82] Furthermore, the tablet was recovered at Uruk,[83] not Babylon (which might have been abandoned at this point).[64]

References

Citations

- Soares 2017, p. 23.

- Karlsson 2017, p. 2.

- Goetze 1964, p. 98.

- Da Riva 2013, p. 72.

- Soares 2017, p. 24.

- Shayegan 2011, p. 260.

- Luckenbill 1924, p. 9.

- Soares 2017, p. 28.

- Karlsson 2017, pp. 6, 11.

- Stevens 2014, p. 68.

- Dandamaev 1989, pp. 185–186.

- Waerzeggers 2018, p. 3.

- Assar 2006, p. 65.

- Boiy 2004, p. 187.

- Steele 1998, p. 193.

- Soares 2017, p. 21.

- Soares 2017, p. 22.

- New Cyrus Cylinder Translation.

- Cyrus Cylinder Translation.

- Peat 1989, p. 199.

- Van Der Meer 1955, p. 42.

- Zaia 2019, p. 3.

- Sancisi-Weerdenburg 2002, p. 579.

- Dandamaev 1993, p. 41.

- Laing & Frost 2017.

- Zaia 2019, p. 4.

- Zaia 2019, p. 6.

- Zaia 2019, p. 7.

- Zaia 2019, pp. 6–7.

- Chen 2020, pp. 202–206.

- Kuhrt 1997, p. 12.

- Mieroop 2015, p. 4.

- Sagona & Zimansky 2009, p. 251.

- Brinkman 1976, pp. 97–98.

- Synchronic King List.

- Brinkman 1999, pp. 183–184.

- Meissner 1999, p. 8.

- Brinkman 1982, pp. 296–297.

- Beaulieu 2018, p. 12.

- Brinkman & Kennedy 1983, p. 63.

- Brinkman 1973, p. 90.

- Van Der Spek 1977, p. 57.

- Frahm 2014, p. 210.

- Porter 1993, p. 67.

- Beaulieu 1997, p. 386.

- Lipschits 2005, p. 16.

- Hanish 2008, p. 32.

- Wiseman 1983, p. 12.

- Nijssen 2018.

- Lendering 2005.

- Bertin 1891, p. 51.

- Van Der Spek 2004.

- Shea 1972, pp. 147–178.

- Dandamaev 1990, pp. 726–729.

- Briant 2002, p. 519.

- Lendering 1998.

- Waerzeggers 2018, p. 12.

- Stevens 2014, p. 72.

- Lendering 2006a.

- Houghton 1979, p. 215.

- Lendering 2006b.

- Sachs & Wiseman 1954, p. 209.

- Van Der Spek 2001, p. 449.

- Brown 2008, p. 77.

- Van Der Spek 2001, p. 451.

- Haubold 2019, p. 276.

- George 2007, p. 64.

- Van Der Spek 2001, p. 450.

- Shayegan 2011, pp. 128-129.

- Assar 2006, p. 58.

- Boiy 2004, p. 172.

- Shayegan 2011, p. 111.

- Schippmann 1986, pp. 647–650.

- Van Der Spek 2001, p. 454.

- Sellwood 1962, p. 73.

- Van Der Spek 2001, p. 455.

- Assar 2006, p. 62.

- Sellwood 1962, pp. 73, 75.

- Assar 2006, pp. 56, 85.

- Assar 2006, pp. 87–88.

- Bivar 1983, p. 49.

- Hunger & de Jong 2014, p. 185.

- Hunger & de Jong 2014, p. 182.

Bibliography

- Assar, Gholamreza F. (2006). A Revised Parthian Chronology of the Period 91-55 BC. Parthica. Incontri di Culture Nel Mondo Antico. 8: Papers Presented to David Sellwood. Istituti Editoriali e Poligrafici Internazionali. ISBN 978-8-881-47453-0. ISSN 1128-6342.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1997). "The Fourth Year of Hostilities in the Land". Baghdader Mitteilungen. 28: 367–394.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Wiley. ISBN 978-1405188999.

- Bertin, G. (1891). "Babylonian Chronology and History". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 5: 1–52.

- Bivar, A.D.H. (1983). "The Political History of Iran Under the Arsacids". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–99. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Boiy, T. (2004). Late Achaemenid and Hellenistic Babylon. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 90-429-1449-1.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. pp. 1–1196. ISBN 9781575061207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brinkman, J. A. (1973). "Sennacherib's Babylonian Problem: An Interpretation". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 25 (2): 89–95. doi:10.2307/1359421. JSTOR 1359421.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1976). Materials and Studies for Kassite History, Vol. I (MSKH I). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1982). "Babylonia, c. 1000 – 748 B.C.". The Cambridge Ancient History (Volume 3, Part 1). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521224963.

- Brinkman, J. A.; Kennedy, D. A. (1983). "Documentary Evidence for the Economic Base of Early Neo-Babylonian Society: A Survey of Dated Babylonian Economic Texts, 721-626 B.C." Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 35 (1/2): 1–90.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1999). Reallexikon Der Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie (Vol 5): Ia – Kizzuwatna. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-007192-4.

- Brown, David (2008). "Increasingly Redundant: The Growing Obsolescence of the Cuneiform Script in Babylonia from 539 BC". In Baines, J.; Bennet, J.; Houston, S. (eds.). The Disappearance of Writing Systems. Perspectives on Literacy and Communication. Equinox. ISBN 978-1845535872.

- Chen, Fei (2020). "A List of Babylonian Kings". Study on the Synchronistic King List from Ashur. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004430921.

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A. (1989). A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004091726.

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A. (1990). "Cambyses II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 7. pp. 726–729.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A. (1993). "Xerxes and the Esagila Temple in Babylon". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 7: 41–45. JSTOR 24048423.

- Da Riva, Rocío (2013). The Inscriptions of Nabopolassar, Amel-Marduk and Neriglissar. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-1614515876.

- Frahm, Eckart (2014). "Family Matters: Psychohistorical Reflections on Sennacherib and His Times". In Kalimi, Isaac; Richardson, Seth (eds.). Sennacherib at the Gates of Jerusalem: Story, History and Historiography. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004265615.

- George, Andrew (2007). "Babylonian and Assyrian: A history of Akkadian" (PDF). The Languages of Iraq: 31–71.

- Goetze, Albrecht (1964). "The Kassites and near Eastern Chronology". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 18 (4): 97–101. doi:10.2307/1359248. JSTOR 1359248.

- Hanish, Shak (2008). "The Chaldean Assyrian Syriac people of Iraq: an ethnic identity problem". Digest of Middle East Studies. 17 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1111/j.1949-3606.2008.tb00145.x.

- Haubold, Johannes (2019). "History and Historiography in the Early Parthian Diaries". In Haubold, Johannes; Steele, John; Stevens, Kathryn (eds.). Keeping Watch in Babylon: The Astronomical Diaries in Context. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004397767.

- Houghton, Arthur (1979). "Timarchus as King in Babylonia". Revue Numismatique. 21: 213–217.

- Hunger, Hermann; de Jong, Teije (2014). "Almanac W22340a From Uruk: The Latest Datable Cuneiform Tablet". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie. 104 (2): 182–194.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2017). "Assyrian Royal Titulary in Babylonia". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kuhrt, A. (1997). Ancient Near East c. 3000–330 BC. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-16763-5.

- Laing, Jennifer; Frost, Warwick (2017). Royal Events: Rituals, Innovations, Meanings. Routledge. ISBN 978-1315652085.

- Lipschits, Oled (2005). The Fall and Rise of Jerusalem: Judah under Babylonian Rule. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575060958.

- Luckenbill, Daniel David (1924). The Annals of Sennacherib. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. OCLC 506728.

- Meissner, Bruno (1999). Reallexikon Der Assyriologie Und Vorderasiatischen Archäologie: Meek - Mythologie. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014809-1.

- Peat, Jerome (1989). "Cyrus "King of Lands," Cambyses "King of Babylon": The Disputed Co-Regency". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 41 (2): 199–216. doi:10.2307/1359915. JSTOR 1359915.

- Porter, Barbara N. (1993). Images, Power, and Politics: Figurative Aspects of Esarhaddon's Babylonian Policy. American Philosophical Society. ISBN 9780871692085.

- Sachs, A. J.; Wiseman, D. J. (1954). "A Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period". Iraq. 16 (2): 202–212. doi:10.2307/4199591. JSTOR 4199591.

- Sagona, A.; Zimansky, P. (2009). Ancient Turkey. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-28916-0.

- Sancisi-Weerdenburg, Heleen (2002). "The Personality of Xerxes, King of Kings". Brill's Companion to Herodotus. BRILL. pp. 579–590. doi:10.1163/9789004217584_026. ISBN 9789004217584.

- Schippmann, K. (1986). "Artabanus (Arsacid kings)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 647–650.

- Sellwood, D. G. (1962). "The Parthian Coins of Gotarzes I, Orodes I and Sinatruces". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, Seventh Series. 2: 73–89.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521766418.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shea, William H. (1972). "An Unrecognized Vassal King of Babylon in the Early Achaemenid Period: Part 4". Andrews University Seminary Studies. 1972: 147–178.

- Soares, Filipe (2017). "The titles 'King of Sumer and Akkad' and 'King of Karduniaš', and the Assyro-Babylonian relationship during the Sargonid Period" (PDF). Rosetta. 19: 20–35.

- Steele, John Michael (1998). "Observations and predictions of eclipse times by astronomers in the pre-telescopic period" (PDF). Durham theses. Durham University.

- Stevens, Kahtryn (2014). "The Antiochus Cylinder, Babylonian Scholarship and Seleucid Imperial Ideology" (PDF). The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 134: 66–88. doi:10.1017/S0075426914000068. JSTOR 43286072.

- Van Der Meer, Petrus (1955). The Chronology of Ancient Western Asia and Egypt. Brill Archive.

- Van Der Mieroop, Marc (2015). A History of the Ancient Near East, ca. 3000-323 BC. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1405149112.

- Van Der Spek, R. (1977). "The struggle of king Sargon II of Assyria against the Chaldaean Merodach-Baladan (710-707 B.C.)". JEOL. 25: 56–66.

- Van Der Spek, R. J. (2001). "The Theatre of Babylon in Cuneiform". Veenhof Anniversary Volume: Studies Presented to Klaas R. Veenhof on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday: 445–456.

- Wiseman, D. J. (1983). Nebuchadnezzar and Babylon. British Academy. ISBN 978-0197261002.

- Zaia, Shana (2019). "Going Native: Šamaš-šuma-ukīn, Assyrian King of Babylon" (PDF). IRAQ.

Web sources

- Farrokh, Kaveh. "A New Translation of the Cyrus Cylinder by the British Museum". kavehfarrokh.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- Nijssen, Daan (2018). "Cyrus the Great". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Lendering, Jona (1998). "Arakha (Nebuchadnezzar IV)". Livius. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Lendering, Jona (2005). "Uruk King List". Livius. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Lendering, Jona (2006). "Antiochus V Eupator". Livius. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- Lendering, Jona (2006). "Alexander I Balas". Livius. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- "Livius - Cyrus Cylinder Translation". www.livius.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Synchronic King List". Livius. 2006. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Van Der Spek, Bert (2004). "CM 4 (Babylonian King List of the Hellenistic Period)". Livius. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Waerzeggers, Caroline (2018). "Introduction: Debating Xerxes' Rule in Babylonia". In Waerzeggers, Caroline; Seire, Maarja (eds.). Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence (PDF). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-3670-6.