Knitting

Knitting is a method by which yarn is manipulated to create a textile or fabric; it is used in many types of garments. Knitting may be done by hand or by machine.

Knitting creates stitches: loops of yarn in a row, either flat or in the round (tubular). There are usually many active stitches on the knitting needle at one time. Knitted fabric consists of a number of consecutive rows of connected loops that intermesh with the next and previous rows. As each row is formed, each newly created loop is pulled through one or more loops from the prior row and placed on the gaining needle so that the loops from the prior row can be pulled off the other needle without unraveling.

Differences in yarn (varying in fibre type, weight, uniformity and twist), needle size, and stitch type allow for a variety of knitted fabrics with different properties, including color, texture, thickness, heat retention, water resistance, and integrity. A small sample of knitwork is known as a swatch.

Structure

Courses and wales

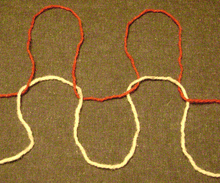

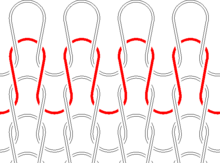

Like weaving, knitting is a technique for producing a two-dimensional fabric made from a one-dimensional yarn or thread. In weaving, threads are always straight, running parallel either lengthwise (warp threads) or crosswise (weft threads). By contrast, the yarn in knitted fabrics follows a meandering path (a course), forming symmetric loops (also called bights) symmetrically above and below the mean path of the yarn. These meandering loops can be easily stretched in different directions giving knit fabrics much more elasticity than woven fabrics. Depending on the yarn and knitting pattern, knitted garments can stretch as much as 500%. For this reason, knitting was initially developed for garments that must be elastic or stretch in response to the wearer's motions, such as socks and hosiery. For comparison, woven garments stretch mainly along one or other of a related pair of directions that lie roughly diagonally between the warp and the weft, while contracting in the other direction of the pair (stretching and contracting with the bias), and are not very elastic, unless they are woven from stretchable material such as spandex. Knitted garments are often more form-fitting than woven garments, since their elasticity allows them to contour to the body's outline more closely; by contrast, curvature is introduced into most woven garments only with sewn darts, flares, gussets and gores, the seams of which lower the elasticity of the woven fabric still further. Extra curvature can be introduced into knitted garments without seams, as in the heel of a sock; the effect of darts, flares, etc. can be obtained with short rows or by increasing or decreasing the number of stitches. Thread used in weaving is usually much finer than the yarn used in knitting, which can give the knitted fabric more bulk and less drape than a woven fabric.

If they are not secured, the loops of a knitted course will come undone when their yarn is pulled; this is known as ripping out, unravelling knitting, or humorously, frogging (because you 'rip it', this sounds like a frog croaking: 'rib-bit').[1] To secure a stitch, at least one new loop is passed through it. Although the new stitch is itself unsecured ("active" or "live"), it secures the stitch(es) suspended from it. A sequence of stitches in which each stitch is suspended from the next is called a wale.[2] To secure the initial stitches of a knitted fabric, a method for casting on is used; to secure the final stitches in a wale, one uses a method of binding/casting off. During knitting, the active stitches are secured mechanically, either from individual hooks (in knitting machines) or from a knitting needle or frame in hand-knitting.

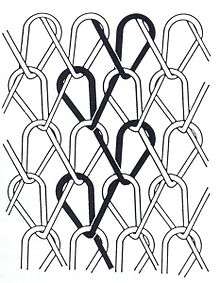

Weft and warp knitting

There are two major varieties of knitting: weft knitting and warp knitting.[3] In the more common weft knitting, the wales are perpendicular to the course of the yarn. In warp knitting, the wales and courses run roughly parallel. In weft knitting, the entire fabric may be produced from a single yarn, by adding stitches to each wale in turn, moving across the fabric as in a raster scan. By contrast, in warp knitting, one yarn is required for every wale. Since a typical piece of knitted fabric may have hundreds of wales, warp knitting is typically done by machine, whereas weft knitting is done by both hand and machine.[4] Warp-knitted fabrics such as tricot and milanese are resistant to runs, and are commonly used in lingerie.

Weft-knit fabrics may also be knit with multiple yarns, usually to produce interesting color patterns. The two most common approaches are intarsia and stranded colorwork. In intarsia, the yarns are used in well-segregated regions, e.g., a red apple on a field of green; in that case, the yarns are kept on separate spools and only one is knitted at any time. In the more complex stranded approach, two or more yarns alternate repeatedly within one row and all the yarns must be carried along the row, as seen in Fair Isle sweaters. Double knitting can produce two separate knitted fabrics simultaneously (e.g., two socks). However, the two fabrics are usually integrated into one, giving it great warmth and excellent drape.

Knit and purl stitches

In securing the previous stitch in a wale, the next stitch can pass through the previous loop from either below or above. If the former, the stitch is denoted as a 'knit stitch' or a 'plain stitch;' if the latter, as a 'purl stitch'. The two stitches are related in that a knit stitch seen from one side of the fabric appears as a purl stitch on the other side.

The two types of stitches have a different visual effect; the knit stitches look like 'V's stacked vertically, whereas the purl stitches look like a wavy horizontal line across the fabric. Patterns and pictures can be created in knitted fabrics by using knit and purl stitches as "pixels"; however, such pixels are usually rectangular, rather than square, depending on the gauge/tension of the knitting. Individual stitches, or rows of stitches, may be made taller by drawing more yarn into the new loop (an elongated stitch), which is the basis for uneven knitting: a row of tall stitches may alternate with one or more rows of short stitches for an interesting visual effect. Short and tall stitches may also alternate within a row, forming a fish-like oval pattern.

In the simplest of hand-knitted fabrics, every row of stitches are all knit (or all purl); this creates a garter stitch fabric. Alternating rows of all knit stitches and all purl stitches creates a stockinette pattern/stocking stitch. Vertical stripes (ribbing) are possible by having alternating wales of knit and purl stitches. For example, a common choice is 2x2 ribbing, in which two wales of knit stitches are followed by two wales of purl stitches, etc. Horizontal striping (welting) is also possible, by alternating rows of knit and purl stitches. Checkerboard patterns (basketweave) are also possible, the smallest of which is known as seed/moss stitch: the stitches alternate between knit and purl in every wale and along every row.

Fabrics in which each knitted row is followed by a purled row, such as in stockinette/stocking stitch, have a tendency to curl—top and bottom curl toward the front (or knitted side) while the sides curl toward the back (or purled side); by contrast, those in which knit and purl stitches are arranged symmetrically (such as ribbing, garter stitch or seed/moss stitch) have more texture and tend to lie flat. Wales of purl stitches have a tendency to recede, whereas those of knit stitches tend to come forward, giving the fabric more stretchability. Thus, the purl wales in ribbing tend to be invisible, since the neighboring knit wales come forward. Conversely, rows of purl stitches tend to form an embossed ridge relative to a row of knit stitches. This is the basis of shadow knitting, in which the appearance of a knitted fabric changes when viewed from different directions.[5]

Typically, a new stitch is passed through a single unsecured ('active') loop, thus lengthening that wale by one stitch. However, this need not be so; the new loop may be passed through an already secured stitch lower down on the fabric, or even between secured stitches (a dip stitch). Depending on the distance between where the loop is drawn through the fabric and where it is knitted, dip stitches can produce a subtle stippling or long lines across the surface of the fabric, e.g., the lower leaves of a flower. The new loop may also be passed between two stitches in the 'present' row, thus clustering the intervening stitches; this approach is often used to produce a smocking effect in the fabric. The new loop may also be passed through 'two or more' previous stitches, producing a decrease and merging wales together. The merged stitches need not be from the same row; for example, a tuck can be formed by knitting stitches together from two different rows, producing a raised horizontal welt on the fabric.

Not every stitch in a row need be knitted; some may be 'missed' (unknitted and passed to the active needle) and knitted on a subsequent row. This is known as slip-stitch knitting.[6] The slipped stitches are naturally longer than the knitted ones. For example, a stitch slipped for one row before knitting would be roughly twice as tall as its knitted counterparts. This can produce interesting visual effects, although the resulting fabric is more rigid because the slipped stitch 'pulls' on its neighbours and is less deformable. Mosaic knitting is a form of slip-stitch knitting that knits alternate colored rows and uses slip stitches to form patterns; mosaic-knit fabrics tend to be stiffer than patterned fabrics produced by other methods such as Fair-Isle knitting.[7]

In some cases, a stitch may be deliberately left unsecured by a new stitch and its wale allowed to disassemble. This is known as drop-stitch knitting, and produces a vertical ladder of see-through holes in the fabric, corresponding to where the wale had been.

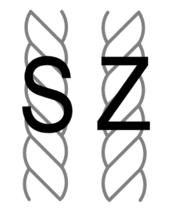

Right- and left-plaited stitches

Both knit and purl stitches may be twisted: usually once if at all, but sometimes twice and (very rarely) thrice. When seen from above, the twist can be clockwise (right yarn over left) or counterclockwise (left yarn over right); these are denoted as right- and left-plaited stitches, respectively. Hand-knitters generally produce right-plaited stitches by knitting or purling through the back loops, i.e., passing the needle through the initial stitch in an unusual way, but wrapping the yarn as usual. By contrast, the left-plaited stitch is generally formed by hand-knitters by wrapping the yarn in the opposite way, rather than by any change in the needle. Although they are mirror images in form, right- and left-plaited stitches are functionally equivalent. Both types of plaited stitches give a subtle but interesting visual texture, and tend to draw the fabric inwards, making it stiffer. Plaited stitches are a common method for knitting jewelry from fine metal wire.

Edges and joins between fabrics

The initial and final edges of a knitted fabric are known as the cast-on and bound/cast-off edges. The side edges are known as the selvages; the word derives from "self-edges", meaning that the stitches do not need to be secured by anything else. Many types of selvages have been developed, with different elastic and ornamental properties.

Vertical and horizontal edges can be introduced within a knitted fabric, e.g., for button holes, by binding/casting off and re-casting on again (horizontal) or by knitting the fabrics on either side of a vertical edge separately.

Two knitted fabrics can be joined by embroidery-based grafting methods, most commonly the Kitchener stitch. New wales can be begun from any of the edges of a knitted fabric; this is known as picking up stitches and is the basis for entrelac, in which the wales run perpendicular to one another in a checkerboard pattern.

Cables, increases, and lace

Ordinarily, stitches are knitted in the same order in every row, and the wales of the fabric run parallel and vertically along the fabric. However, this need not be so, since the order in which stitches are knitted may be permuted so that wales cross over one another, forming a cable pattern. Cables patterns tend to draw the fabric together, making it denser and less elastic;[8] Aran sweaters are a common form of knitted cabling.[9] Arbitrarily complex braid patterns can be done in cable knitting, with the proviso that the wales must move ever upwards; it is generally impossible for a wale to move up and then down the fabric. Knitters have developed methods for giving the illusion of a circular wale, such as appear in Celtic knots, but these are inexact approximations. However, such circular wales are possible using Swiss darning, a form of embroidery, or by knitting a tube separately and attaching it to the knitted fabric.

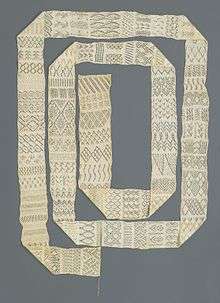

A wale can split into two or more wales using increases, most commonly involving a yarn over. Depending on how the increase is done, there is often a hole in the fabric at the point of the increase. This is used to great effect in lace knitting, which consists of making patterns and pictures using such holes, rather than with the stitches themselves.[10] The large and many holes in lacy knitting makes it extremely elastic; for example, some Shetland "wedding-ring" shawls are so fine that they may be drawn through a wedding ring.

By combining increases and decreases, it is possible to make the direction of a wale slant away from vertical, even in weft knitting. This is the basis for bias knitting, and can be used for visual effect, similar to the direction of a brush-stroke in oil painting.

Ornamentations and additions

Various point-like ornaments may be added to knitting for their look or to improve the wear of the fabric. Examples include various types of bobbles, sequins and beads. Long loops can also be drawn out and secured, forming a "shaggy" texture to the fabric; this is known as loop knitting. Additional patterns can be made on the surface of the knitted fabric using embroidery; if the embroidery resembles knitting, it is often called Swiss darning. Various closures for the garments, such as frogs and buttons can be added; usually buttonholes are knitted into the garment, rather than cut.

Ornamental pieces may also be knitted separately and then attached using applique. For example, differently colored leaves and petals of a flower could be knit separately and attached to form the final picture. Separately knitted tubes can be applied to a knitted fabric to form complex Celtic knots and other patterns that would be difficult to knit.

Unknitted yarns may be worked into knitted fabrics for warmth, as is done in tufting and "weaving" (also known as "couching").

History and culture

The word is derived from knot and ultimately from the Old English cnyttan, to knot.[11]

The exact origins of knitting are unknown, the earliest known examples being cotton socks found in Egyptian pyramids.[12]

Nålebinding (Danish: literally "binding with a needle" or "needle-binding") is a fabric creation technique predating both knitting and crochet.

The first commercial knitting guilds appear in Western Europe in the early fifteenth century (Tournai in 1429, Barcelona in 1496). The Guild of Saint Fiacre was founded in Paris in 1527 but the archives mention an organization (not necessarily a guild) of knitters from 1268.[13]

With the invention of the stocking frame, an early form of knitting machine, knitting "by hand" became a craft used by country people with easy access to fiber. Similar to quilting, spinning, and needlepoint, hand knitting became a leisure activity for the wealthy. English Roman Catholic priest and a former Anglican bishop, Richard Rutt, authored a history of the craft in A History of Hand Knitting (Batsford, 1987). His collection of books about knitting is now housed at the Winchester School of Art (University of Southampton).

Properties of fabrics

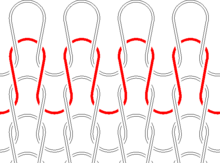

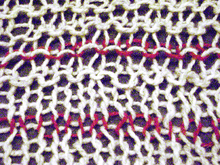

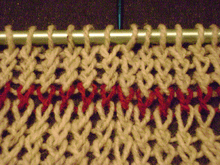

The topology of a knitted fabric is relatively complex. Unlike woven fabrics, where strands usually run straight horizontally and vertically, yarn that has been knitted follows a looped path along its row, as with the red strand in the diagram at left, in which the loops of one row have all been pulled through the loops of the row below it.

Because there is no single straight line of yarn anywhere in the pattern, a knitted piece of fabric can stretch in all directions. This elasticity is all but unavailable in woven fabrics which only stretch along the bias. Many modern stretchy garments, even as they rely on elastic synthetic materials for some stretch, also achieve at least some of their stretch through knitted patterns.

The basic knitted fabric (as in the diagram, and usually called a stocking or stockinette pattern) has a definite "right side" and "wrong side". On the right side, the visible portions of the loops are the verticals connecting two rows which are arranged in a grid of V shapes. On the wrong side, the ends of the loops are visible, both the tops and bottoms, creating a much more bumpy texture sometimes called reverse stockinette. (Despite being the "wrong side," reverse stockinette is frequently used as a pattern in its own right.) Because the yarn holding rows together is all on the front, and the yarn holding side-by-side stitches together is all on the back, stockinette fabric has a strong tendency to curl toward the front on the top and bottom, and toward the back on the left and right side.

Stitches can be worked from either side, and various patterns are created by mixing regular knit stitches with the "wrong side" stitches, known as purl stitches, either in columns (ribbing), rows (garter, welting), or more complex patterns. Each fabric has different properties: a garter stitch has much more vertical stretch, while ribbing stretches much more horizontally. Because of their front-back symmetry, these two fabrics have little curl, making them popular as edging, even when their stretch properties are not desired.

Different combinations of knit and purl stitches, along with more advanced techniques, generate fabrics of considerably variable consistency, from gauzy to very dense, from highly stretchy to relatively stiff, from flat to tightly curled, and so on.

Texture

The most common texture for a knitted garment is that generated by the flat stockinette stitch—as seen, though very small, in machine-made stockings and T-shirts—which is worked in the round as nothing but knit stitches, and worked flat as alternating rows of knit and purl. Other simple textures can be made with nothing but knit and purl stitches, including garter stitch, ribbing, and moss and seed stitches. Adding a "slip stitch" (where a loop is passed from one needle to the other) allows for a wide range of textures, including heel and linen stitches as well as a number of more complicated patterns.

Some more advanced knitting techniques create a surprising variety of complex textures. Combining certain increases, which can create small eyelet holes in the resulting fabric, with assorted decreases is key to creating knitted lace, a very open fabric resembling needle or bobbin lace. Open vertical stripes can be created using the drop-stitch knitting technique. Changing the order of stitches from one row to the next, usually with the help of a cable needle or stitch holder, is key to cable knitting, producing an endless variety of cables, honeycombs, ropes, and Aran sweater patterning. Entrelac forms a rich checkerboard texture by knitting small squares, picking up their side edges, and knitting more squares to continue the piece.

Fair Isle knitting uses two or more colored yarns to create patterns and forms a thicker and less flexible fabric.

The appearance of a garment is also affected by the weight of the yarn, which describes the thickness of the spun fibre. The thicker the yarn, the more visible and apparent stitches will be; the thinner the yarn, the finer the texture.

Color

Plenty of finished knitting projects never use more than a single color of yarn, but there are many ways to work in multiple colors. Some yarns are dyed to be either variegated (changing color every few stitches in a random fashion) or self-striping (changing every few rows). More complicated techniques permit large fields of color (intarsia, for example), busy small-scale patterns of color (such as Fair Isle), or both (double knitting and slip-stitch color, for example).

Yarn with multiple shades of the same hue are called ombre, while a yarn with multiple hues may be known as a given colorway; a green, red and yellow yarn might be dubbed the "Parrot Colorway" by its manufacturer, for example. Heathered yarns contain small amounts of fibre of different colours, while tweed yarns may have greater amounts of different colored fibres.

Hand knitting process

There are many hundreds of different knitting stitches used by hand knitters. A piece of hand knitting begins with the process of casting on, which involves the initial creation of the stitches on the needle. Different methods of casting on are used for different effects: one may be stretchy enough for lace, while another provides a decorative edging. Provisional cast-ons are used when the knitting will continue in both directions from the cast-on. There are various methods employed to cast on, such as the "thumb method" (also known as "slingshot" or "long-tail" cast-ons), where the stitches are created by a series of loops that will, when knitted, give a very loose edge ideal for "picking up stitches" and knitting a border; the "double needle method" (also known as "knit-on" or "cable cast-on"), whereby each loop placed on the needle is then "knitted on," which produces a firmer edge ideal on its own as a border; and many more. The number of active stitches remains the same as when cast on unless stitches are added (an increase) or removed (a decrease).

Most Western-style hand knitters follow either the English style (in which the yarn is held in the right hand) or the Continental style (in which the yarn is held in the left hand).

There are also different ways to insert the needle into the stitch. Knitting through the front of a stitch is called Western knitting. Going through the back of a stitch is called Eastern knitting. A third method, called combination knitting, goes through the front of a knit stitch and the back of a purl stitch.[14]

Once the hand knitted piece is finished, the remaining live stitches are "cast off". Casting (or "binding") off loops the stitches across each other so they can be removed from the needle without unravelling the item. Although the mechanics are different from casting on, there is a similar variety of methods.

In hand knitting certain articles of clothing, especially larger ones like sweaters, the final knitted garment will be made of several knitted pieces, with individual sections of the garment hand knitted separately and then sewn together. Seamless knitting, where a whole garment is hand knit as a single piece, is also possible. Elizabeth Zimmermann is probably the best-known proponent of seamless or circular hand knitting techniques. Smaller items, such as socks and hats, are usually knit in one piece on double-pointed needles or circular needles. Hats in particular can be started "top down" on double pointed needles with the increases added until the preferred size is achieved, switching to an appropriate circular needle when enough stitches have been added. Care must be taken to bind off at a tension that will allow the "give" needed to comfortably fit on the head. (See Circular knitting.)

Materials

Yarn

Yarn for hand-knitting is usually sold as balls or skeins (hanks), and it may also be wound on spools or cones. Skeins and balls are generally sold with a yarn-band, a label that describes the yarn's weight, length, dye lot, fiber content, washing instructions, suggested needle size, likely gauge/tension, etc. It is common practice to save the yarn band for future reference, especially if additional skeins must be purchased. Knitters generally ensure that the yarn for a project comes from a single dye lot. The dye lot specifies a group of skeins that were dyed together and thus have precisely the same color; skeins from different dye-lots, even if very similar in color, are usually slightly different and may produce a visible horizontal stripe when knitted together. If a knitter buys insufficient yarn of a single dye lot to complete a project, additional skeins of the same dye lot can sometimes be obtained from other yarn stores or online. Otherwise, knitters can alternate skeins every few rows to help the dye lots blend together easier.

The thickness or weight of the yarn is a significant factor in determining the gauge/tension, i.e., how many stitches and rows are required to cover a given area for a given stitch pattern. Thicker yarns generally require thicker knitting needles, whereas thinner yarns may be knit with thick or thin needles. Hence, thicker yarns generally require fewer stitches, and therefore less time, to knit up a given garment. Patterns and motifs are coarser with thicker yarns; thicker yarns produce bold visual effects, whereas thinner yarns are best for refined patterns. Yarns are grouped by thickness into six categories: superfine, fine, light, medium, bulky and superbulky; quantitatively, thickness is measured by the number of wraps per inch (WPI). In the British Commonwealth (outside North America) yarns are measured as 1ply, 2ply, 3ply, 4ply, 5ply, 8ply (or double knit),10ply and 12ply (triple knit). The related weight per unit length is usually measured in tex or denier.

Before knitting, the knitter will typically transform a hank/skein into a ball where the yarn emerges from the center of the ball; this making the knitting easier by preventing the yarn from becoming easily tangled. This transformation may be done by hand, or with a device known as a ballwinder. When knitting, some knitters enclose their balls in jars to keep them clean and untangled with other yarns; the free yarn passes through a small hole in the jar-lid.

A yarn's usefulness for a knitting project is judged by several factors, such as its loft (its ability to trap air), its resilience (elasticity under tension), its washability and colorfastness, its hand (its feel, particularly softness vs. scratchiness), its durability against abrasion, its resistance to pilling, its hairiness (fuzziness), its tendency to twist or untwist, its overall weight and drape, its blocking and felting qualities, its comfort (breathability, moisture absorption, wicking properties) and of course its look, which includes its color, sheen, smoothness and ornamental features. Other factors include allergenicity; speed of drying; resistance to chemicals, moths, and mildew; melting point and flammability; retention of static electricity; and the propensity to become stained and to accept dyes. Different factors may be more significant than others for different knitting projects, so there is no one "best" yarn. The resilience and propensity to (un)twist are general properties that affect the ease of hand-knitting. More resilient yarns are more forgiving of irregularities in tension; highly twisted yarns are sometimes difficult to knit, whereas untwisting yarns can lead to split stitches, in which not all the yarn is knitted into a stitch. A key factor in knitting is stitch definition, corresponding to how well complicated stitch patterns can be seen when made from a given yarn. Smooth, highly spun yarns are best for showing off stitch patterns; at the other extreme, very fuzzy yarns or eyelash yarns have poor stitch definition, and any complicated stitch pattern would be invisible.

Although knitting may be done with ribbons, metal wire or more exotic filaments, most yarns are made by spinning fibers. In spinning, the fibers are twisted so that the yarn resists breaking under tension; the twisting may be done in either direction, resulting in a Z-twist or S-twist yarn. If the fibers are first aligned by combing them, the yarn is smoother and called a worsted; by contrast, if the fibers are carded but not combed, the yarn is fuzzier and called woolen-spun. The fibers making up a yarn may be continuous filament fibers such as silk and many synthetics, or they may be staples (fibers of an average length, typically a few inches); naturally filament fibers are sometimes cut up into staples before spinning. The strength of the spun yarn against breaking is determined by the amount of twist, the length of the fibers and the thickness of the yarn. In general, yarns become stronger with more twist (also called worst), longer fibers and thicker yarns (more fibers); for example, thinner yarns require more twist than do thicker yarns to resist breaking under tension. The thickness of the yarn may vary along its length; a slub is a much thicker section in which a mass of fibers is incorporated into the yarn.

The spun fibers are generally divided into animal fibers, plant and synthetic fibers. These fiber types are chemically different, corresponding to proteins, carbohydrates and synthetic polymers, respectively. Animal fibers include silk, but generally are long hairs of animals such as sheep (wool), goat (angora, or cashmere goat), rabbit (angora), llama, alpaca, dog, cat, camel, yak, and muskox (qiviut). Plants used for fibers include cotton, flax (for linen), bamboo, ramie, hemp, jute, nettle, raffia, yucca, coconut husk, banana fiber, soy and corn. Rayon and acetate fibers are also produced from cellulose mainly derived from trees. Common synthetic fibers include acrylics,[15] polyesters such as dacron and ingeo, nylon and other polyamides, and olefins such as polypropylene. Of these types, wool is generally favored for knitting, chiefly owing to its superior elasticity, warmth and (sometimes) felting. It is also common to blend different fibers in the yarn, e.g., 85% alpaca and 15% silk. Even within a type of fiber, there can be great variety in the length and thickness of the fibers; for example, Merino wool and Egyptian cotton are favored because they produce exceptionally long, thin (fine) fibers for their type.

A single spun yarn may be knitted as is, or braided or plied with another. In plying, two or more yarns are spun together, almost always in the opposite sense from which they were spun individually; for example, two Z-twist yarns are usually plied with an S-twist. The opposing twist relieves some of the yarns' tendency to curl up and produces a thicker, balanced yarn. Plied yarns may themselves be plied together, producing cabled yarns or multi-stranded yarns. Sometimes, the yarns being plied are fed at different rates, so that one yarn loops around the other, as in bouclé. The single yarns may be dyed separately before plying, or afterwards to give the yarn a uniform look.

The dyeing of yarns is a complex art that has a long history. However, yarns need not be dyed. They may be dyed just one color, or a great variety of colors. Dyeing may be done industrially, by hand or even hand-painted onto the yarn. A great variety of synthetic dyes have been developed since the synthesis of indigo dye in the mid-19th century; however, natural dyes are also possible, although they are generally less brilliant. The color-scheme of a yarn is sometimes called its colorway. Variegated yarns can produce interesting visual effects, such as diagonal stripes; conversely, a variegated yarn may obscure a detailed knitting design, such as a cable or lace pattern.

Metal Wire

There are multiple commercial applications for knit fabric made of metal wire by knitting machines. Steel wire of various sizes may be used for electric and magnetic shielding due to its conductivity. Stainless steel may be used in a coffee press for its rust resistance.

Metal wire can also be used as jewelry.

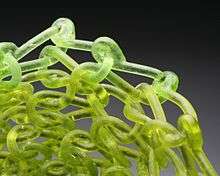

Glass/Wax

Knitted glass combines knitting, lost-wax casting, mold-making, and kiln-casting. The process involves

- knitting with wax strands,[16]

- surrounding the knitted wax piece with a heat-tolerant refractory material,

- removing the wax by melting it out, thus creating a mold;

- placing the mold in a kiln where lead crystal glass melts into the mold;

- after the mold cools, the mold material is removed to reveal the knitted glass piece.[17]

Tools

The process of knitting has three basic tasks:

- the active (unsecured) stitches must be held so they don't drop

- these stitches must be released sometime after they are secured

- new bights of yarn must be passed through the fabric, usually through active stitches, thus securing them.

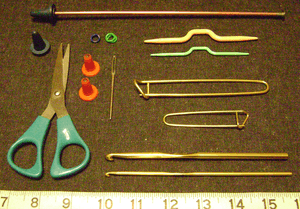

In very simple cases, knitting can be done without tools, using only the fingers to do these tasks; however, knitting is usually carried out using tools such as knitting needles, knitting machines or rigid frames. Depending on their size and shape, the rigid frames are called stocking frames, knitting boards, knitting rings (also called knitting looms) or knitting spools (also known as knitting knobbies, knitting nancies, or corkers). There is also a technique called knooking[18] of knitting with a crochet hook that has a cord attached to the end, to hold the stitches while they're being worked. Other tools are used to prepare yarn for knitting, to measure and design knitted garments, or to make knitting easier or more comfortable.

Needles

There are three basic types of knitting needles (also called "knitting pins"). The first and most common type consists of two slender, straight sticks tapered to a point at one end, and with a knob at the other end to prevent stitches from slipping off. Such needles are usually 10–16 inches (250–410 mm) long but, due to the compressibility of knitted fabrics, may be used to knit pieces significantly wider. The most important property of needles is their diameter, which ranges from below 2 to 25 mm (roughly 1 inch). The diameter affects the size of stitches, which affects the gauge/tension of the knitting and the elasticity of the fabric. Thus, a simple way to change gauge/tension is to use different needles, which is the basis of uneven knitting. Although the diameter of the knitting needle is often measured in millimeters, there are several measurement systems, particularly those specific to the United States, the United Kingdom and Japan; a conversion table is given at knitting needle. Such knitting needles may be made out of any materials, but the most common materials are metals, wood, bamboo, and plastic. Different materials have different frictions and grip the yarn differently; slick needles such as metallic needles are useful for swift knitting, whereas rougher needles such as bamboo offer more friction and are therefore less prone to dropping stitches. The knitting of new stitches occurs only at the tapered ends. Needles with lighted tips have been sold to allow knitters to knit in the dark.

The second type of knitting needles are straight, double-pointed knitting needles (also called "DPNs"). Double-pointed needles are tapered at both ends, which allows them to be knit from either end. DPNs are typically used for circular knitting, especially smaller tube-shaped pieces such as sleeves, collars, and socks; usually one needle is active while the others hold the remaining active stitches. DPNs are somewhat shorter (typically 7 inches) and are usually sold in sets of four or five.

The third needle type consists of circular needles, which are long, flexible double-pointed needles. The two tapered ends (typically 5 inches (130 mm) long) are rigid and straight, allowing for easy knitting; however, the two ends are connected by a flexible strand (usually nylon) that allows the two ends to be brought together. Circular needles are typically 24-60 inches long, and are usually used singly or in pairs; again, the width of the knitted piece may be significantly longer than the length of the circular needle. Interchangeable needles are a subset of circular needles. They are kits consist of pairs of needles with usually nylon cables or cords. The cables/cords are screwed into the needles, allowing the knitter to have both flexible straight needles or circular needles. This also allows the knitter to change the diameter and length of the needles as needed. The needles must be screwed on tightly, otherwise yarn can snag and become damaged.

The ability to work from either end of one needle is convenient in several types of knitting, such as slip-stitch versions of double knitting. Circular needles may be used for flat or circular knitting.

Cable needles are a special case of DPNs, although they are usually not straight, but dimpled in the middle. Often, they have the form of a hook. When cabling a knitted piece, a hook is easier to grab and hold the yarn. Cable needles are typically very short (a few inches), and are used to hold stitches temporarily while others are being knitted. When in use, the cable needle is used at the same time as two regular needles. At specific points indicated by the knitting pattern, the cable needle is moved, the stitches on it are worked by the other needles, then the cable needle is turned around to a different position to create the cable twist.

Cable needles are a specific design, and are used to create the twisting motif of a knitted cable. They are made in different sizes, which produces cables of different widths.

Largest circular knitting needles

The largest aluminum circular knitting needles on record are size US 150 and are nearly 7 feet tall. They are owned by Paradise Fibers and are currently on display in the Paradise Fibers retail showroom.

Record

The current holder of the Guinness World Record for Knitting with the Largest Knitting Needles is Julia Hopson[19] of Penzance in Cornwall.

Julia knitted a square of ten stitches and ten rows in stockinette stitch using knitting needles that were 6.5 centimeters in diameter and 3.5 meters long.

Ancillary tools

Various tools have been developed to make hand-knitting easier. Tools for measuring needle diameter and yarn properties have been discussed above, as well as the yarn swift, ballwinder and "yarntainers". Crochet hooks and a darning needle are often useful in binding/casting off or in joining two knitted pieces edge-to-edge. The darning needle is used in duplicate stitch (also known as Swiss darning). The crochet hook is also essential for repairing dropped stitches and some specialty stitches such as tufting. Other tools such as knitting spools or pom-pom makers are used to prepare specific ornaments. For large or complex knitting patterns, it is sometimes difficult to keep track of which stitch should be knit in a particular way; therefore, several tools have been developed to identify the number of a particular row or stitch, including circular stitch markers, hanging markers, extra yarn and row counters. A second potential difficulty is that the knitted piece will slide off the tapered end of the needles when unattended; this is prevented by "point protectors" that cap the tapered ends. Another problem is that too much knitting may lead to hand and wrist troubles; for this, special stress-relieving gloves are available. In traditional Shetland knitting a special belt is often used to support the end of one needle allowing the knitting greater speed. Finally, there are sundry bags and containers for holding knitting, yarns and needles.

Knitting Styles

Techniques for Holding Yarn

Continental Style

Continental knitting is achieved by holding the yarn in your left hand for both knitting and purling. Patterns are created on the outside (public-facing) side of the piece.

English Style

English-style knitting is achieved by holding the yarn in your right hand. Patterns are created on the outside (public-facing) side of the piece.

Portuguese/ Incan/ Turkish Style

This style is achieved by carrying the yarn around the neck or from a necklace-style hook, allowing the knitter to knit on the reverse (purl) side, e.g. "inside out" compared to Western knitting techniques. Patterns are typically created by stranding the yarn on the outside of the piece. This is an ancient style of knitting, which spread from Arabic culture to the Iberian peninsula, during its occupation by Muslims. Thence this style was taught to Indigenous South Americans, during conquest by Spanish/Portuguese colonists.

Mega Knitting

Mega knitting is a term recently coined and relates to the use of knitting needles greater than or equal to half an inch in diameter.

Mega knitting uses the same stitches and techniques as conventional knitting, except that hooks are carved into the ends of the needles. The hooked needles greatly enhance control of the work, catching the stitches and preventing them from slipping off.

It was the development of the knitting machine that introduced hooked needles and enabled faultless, automated knitting. The hook catches the loop of yarn as each stitch is knitted, meaning that wrists and fingers do not have to work so hard and there is less chance of stitches slipping off the needle. The position of the hook is most important. Turn the left (non-working) hook to face away at all times; turn the right (working) hook toward you up whilst knitting (plain stitch) and away whilst purling.

Mega knitting produces a chunky, bulky fabric or an open lacy weave, depending on the weight and type of yarn used.[20]

Micro knitting

Micro knitting or miniature knitting uses extremely fine threads and needles. Anthea Crome created 14 tiny sweaters used in the stop motion animated film Coraline and has made objects at 60 or 80 stitches per inch, making her own needles from fine surgical steel wire.[21][22][23] She has published Bugknits: Extreme knitting for hobbyists, artists and knitters (2009, Blurb: ISBN 978-1320025546). Annelies de Kort has knitted on an even smaller scale and has used needles of 0.4mm.[24][25]

Commercial applications

Industrially, metal wire is also knitted into a metal fabric for a wide range of uses including the filter material in cafetieres, catalytic converters for cars and many other uses. These fabrics are usually manufactured on circular knitting machines that would be recognized by conventional knitters as sock machines.

Many fashion designers make heavy use of knitted fabric in their fashion collections. Gordana Gelhausen, who appeared in season six of the television show Project Runway, is primarily a knit designer. Other designers and labels that make heavy use of knitting include Michael Kors, Fendi, and Marc Jacobs.

For individual hobbyists, websites such as Etsy, Big Cartel and Ravelry have made it easy to sell knitting patterns on a small scale, in a way similar to eBay.

Graffiti

In the last decade, a practice called knitting graffiti, guerilla knitting, or yarn bombing—the use of knitted or crocheted cloth to modify and beautify one's (usually outdoor) surroundings—emerged in the U.S. and spread worldwide.[26] Magda Sayeg is credited with starting the movement in the US and Knit the City are a prominent group of graffiti knitters in the United Kingdom.[27] Yarn bombers sometimes target existing pieces of graffiti for beautification. For instance, Dave Cole is a contemporary sculpture artist who practiced knitting as graffiti for a large-scale public art installation in Melbourne, Australia for the Big West Arts Festival in 2009. The work was vandalized the night of its completion.[28] A new movie, shot by a Tasmanian filmmaker on a set made almost entirely out of yarn, was partially inspired by "knitted graffiti".[29]

Yarn Crawl

Many major metropolitan cities across the US and Europe host annual Yarn Crawls. The event is typically a multi-day event that caters to all knitters, crochet and yarn enthusiasts that supports the local crafting community. Over the multi-day period, multiple local yarn and knit shops participate in the yarn crawl and offer up store discounts, give away free exclusive patterns, provide classes, trunk shows and conduct raffles for prizes. Participants of the crawl receive a passport and get their passport stamped at each store they visit along the crawl. Traditionally those that get their passports fully stamped are eligible to win a larger gift basket filled with yarn, knitting and crochet goodies. Some local crawls also provide a Knit-Along (KAL) or Crochet-Along (CAL) where attendees follow a specific pattern prior to the crawl and then proudly wear it during the crawl for others to see.[30][31][32][33]

Charity

Hand knitting garments for free distribution to others has become common practice among hand knitting groups. Girls and women hand knitted socks, sweaters, scarves, mittens, gloves, and hats for soldiers in Crimea, the American Civil War, and the Boer Wars; this practice continued in World War I, World War II and the Korean War, and continues for soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Australian charity Wrap with Love continues to provide blankets hand knitted by volunteers to people most in need around the world who have been affected by war.

In the historical projects, yarn companies provided knitting patterns approved by the various branches of the armed services; often they were distributed by local chapters of the American Red Cross. Modern projects usually entail the hand knitting of hats or helmet liners; the liners provided for soldiers must be of 100% worsted weight wool and be crafted using specific colors.

.jpg)

Clothing and afghans are frequently made for children, the elderly, and the economically disadvantaged in various countries. Pine Ridge Indian Reservation accepts donations for the Lakota people in the United States. Prayer shawls, or shawls in which the crafter meditates or says prayers of their faith while hand knitting with the intent on comforting the recipient, are donated to those experiencing loss or stress. Many knitters today hand knit and donate "chemo caps," soft caps for cancer patients who lose their hair during chemotherapy. Yarn companies offer free knitting patterns for these caps.

Penguin sweaters were hand knitted by volunteers for the rehabilitation of penguins contaminated by exposure to oil slicks. The project is now complete.[34]

Chicken sweaters were also hand knitted to aid battery hens that had lost their feathers. The organization is not currently accepting donations, but maintains a list of volunteers.[35]

Originally started after the 2004 Indonesian tsunami, Knitters Without Borders[36] is a charity challenge issued by knitting personality Stephanie Pearl-McPhee that encourages hand knitters to donate to Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders). Instead of[hand knitting for charity, knitters are encouraged to donate a week's worth of disposable income, including money that otherwise might have been spent on yarn. Knitted items are occasional offered as prizes to donors. As of September 2011, Knitters Without Borders donors have contributed CAD$1,062,217.[37]

Security blankets can also be made through the Project Linus organization which helps needy children.[38]

There are organizations that help reach other countries in need such as afghans for Afghans. This outreach is described as, "afghans for Afghans is a humanitarian and educational people-to-people project that sends hand-knit and crocheted blankets and sweaters, vests, hats, mittens, and socks to the beleaguered people of Afghanistan."[39]

The knitters of the Little Yellow Duck Project craft small yellow ducks which are left for others to find, as a random act of kindness and to raise awareness of blood donation and organ donation. The project was started in memory of a young woman who had collected plastic toy ducks and who died from cystic fibrosis while waiting for a lung transplant. Finders of the ducks are encouraged to log them on a website, which as of May 2020 shows that 12,265 ducks have been found in 106 countries.[40]

Health benefits

Studies have shown that hand knitting, along with other forms of needlework, provide several significant health benefits. These studies have found the rhythmic and repetitive action of hand knitting can help prevent and manage stress, pain and depression, which in turn strengthens the body's immune system,[41] as well as create a relaxation response in the body which can decrease blood pressure, heart rate, help prevent illness, and have a calming effect. Pain specialists have also found that hand knitting changes brain chemistry, resulting in an increase in "feel good" hormones (i.e. serotonin and dopamine) and a decrease in stress hormones.[41]

Hand knitting, along with other leisure activities, has been linked to reducing the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease and dementia. Much like physical activity strengthens the body, mental exercise makes the human brain more resilient.[42]

A repository of research into the effect on health of hand knitting can be found at Stitch links,[43] an organization founded in Bath, England.

Knitting also helps in the area of social interaction; knitting provides people with opportunities to socialize with others. Some ways to increase social interaction with knitting is inviting friends over to knit and chat with each other. Even if they've never knitted before this can be a fun way to interact with friends.[2] Many public libraries and yarn stores host knitting groups where knitters can meet locally to engage with others interested in hand crafts.

Another interesting way that knitting can positively impact one's life is improving the dexterity in your hands and fingers. This keeps the fingers limber and can be especially helpful for those with arthritis. Knitting can reduce the pain of arthritis if people make it a daily habit.[2]

See also

References

- "Techniques with Theresa, Frog pond edition".

- A wale, according to Knitting Technology: a Comprehensive Handbook and Practical Guide, is "a predominantly vertical column of needle loops generally produced by the same needles at successive (not necessarily all) knitting cycles. A wale starts as soon as an empty needle starts to knit" (Spencer 1989:17).

- "Knitting Basics". Alamac American Knits LLC. 2004. Archived from the original on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- (Spencer 1989:11–12)

- Høxbro, Vivian (2004). Shadow Knitting. Loveland, CO: Interweave Press. ISBN 978-1-931499-41-5.

- Bartlett, Roxana (1998). Slip-Stitch Knitting: Color Pattern the Easy Way. Loveland, CO: Interweave Press. ISBN 978-1-883010-32-4.

- Starmore, Alice (1988). Alice Starmore's Book of Fair Isle Knitting. Taunton. ISBN 978-0-918804-97-6.

- Leapman, Melissa (2006). Cables Untangled: An Exploration of Cable Knitting. Potter Craft. ISBN 978-1-4000-9745-6.

- Hollingworth, Shelagh (1983). The Complete Book of Traditional Aran Knitting. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-15635-0.

- Sowerby, Jane (2006). Victorian Lace Today. XRX Books. ISBN 978-1-933064-07-9.

Swansen, Meg (2005). A Gathering of Lace (2nd ed.). Schoolhouse Press. ISBN 978-1-893762-24-4. - Games, Alex (2007). Balderdash & piffle : one sandwich short of a dog's dinner. London: BBC. ISBN 978-1-84607-235-2.

- Tissus d'Égypte: témoins du monde arabe, VIIIe. - XVe. siècles. Collection Bouvier, Exposition 1993-1994, Musée d'art et d'histoire à Genève. 1994, Institut du monde arabe à Paris. ISBN 9782908528527.

- Brewer, John; Porter, Roy, eds. (1994). Consumption and the World of Goods. London: Routledge. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-415-11478-3. LCCN 93180136.

- Finlay, Amy. "How to do the knit stitch". Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 28 December 2006.

- Masson, James (1995). Acrylic Fiber Technology and Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc. p. 172. ISBN 0-8247-8977-6.

- "Knitting With Glass – Impossible!?". 5 October 2011.

- "Knitting glass (Fiberarts Magazine Summer Issue 2011)" (PDF). carolmilne.com.

- "I'd Rather Be Knooking". Retrieved 9 July 2011.

- "It's official: Julia gains Guinness World Record for knitting with the largest knitting needles in the world". knitwitspenzance.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- "House of Fiber". 13 December 2015.

- McNichol, Tom (24 July 2012). "Hollywood Knights". Portland Monthly. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Nargi, Lela (2011). "Anthea Crome: World's smallest knitwear". Astounding Knits!: 101 Spectacular Knitted Creations and Daring Feats. Voyageur Press. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-0-7603-3845-2. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Partlow, Mia. "Seventy Stitches To The Inch: Althea Crome's Tiny Knits". Arts & Culture - Indiana Public Media. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Nargi, Lela (2011). "Annelies de Kort". Astounding Knits!: 101 Spectacular Knitted Creations and Daring Feats. Voyageur Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-7603-3845-2. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- "Site Annelies de Kort". www.anneliesdekort.nl. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Anonymous (21 January 2009). "Knitters turn to graffiti artists with 'yarnbombing'". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 25 May 2009.

- Costa, Maddy (10 October 2010). "The graffiti knitting epidemic". The Guardian. London.

- Russell, Mark (29 November 2009). "Artists in pink fit as Big Knit vandal unravels artwork". The Age. Melbourne.

- Breen, Fiona (4 November 2012). "A new movie, shot by a Tasmanian filmmaker on a set made almost entirely out of yarn, was partially inspired by "knitted graffiti"". ABC. Tasmania.

- "Basics |". www.rosecityyarncrawl.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "NYC Yarn Crawl - About". NYC Yarn Crawl 2016. Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Great London Yarn Crawl 2016". Yarn in the City. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- "Triangle Yarn Crawl". Triangle Yarn Crawl. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Tasmanian Conservation Trust. "Penguin Conservation in Tasmania". Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Eglen, Jo (2008). "Hens and their jumpers". Little Hen Rescue. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- "Yarn Harlot: TSF FAQ".

- Stephanie Pearl-McPhee. "Knitters Without Borders". Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- "Project Linus-Home".

- "afghans for Afghans --".

- "World Map". The Little Yellow Duck Project. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- Publishing, Prime. "Knitting And Crochet Offer Long-term Health Benefits".

- Scarmeas, N.; Manly, Stern; Tang, Levy (26 December 2001). "Influence of leisure activity on the incidence of Alzheimer's Disease". Neurology. 57 (12): 2236–2242. doi:10.1212/wnl.57.12.2236. PMC 3025284. PMID 11756603.

- "Stitchlinks.com".

Further reading

- Hiatt, June Hemmons. (2012). The principles of knitting: Methods and techniques of hand knitting. Simon & Schuster, New York.

- "Knitting". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Columbia University Press. 2003.

- Rutt, Richard (2003). A History of Hand Knitting. Interweave Press, Loveland, CO. (Reprint Edition ISBN)

- Spencer, David J. (1989). Knitting Technology: a Comprehensive Handbook and Practical Guide. Lancaster: Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 1-85573-333-1.

- Stoller, Debbie. (2004) Stitch 'n Bitch: The Knitter's Handbook. Workman Publishing Company

- Thomas, Mary (1972) [1938]. Mary Thomas's Knitting Book. Dover Publications. New York.

- Zimmermann, Elizabeth. (1972). Knitting Without Tears. Simon & Schuster, New York. (Reprint Edition ISBN)

- Gschwandtner, Sabrina. (2007). KnitKnit: Profiles and Projects from Knitting's New Wave. Stewart, Tabori and Chang, New York.

- Patel, Aneeta. (2008) Knitty Gritty - Knitting for the Absolute Beginner. A&C Black

- Zimmermann, Elizabeth. (1981) Elizabeth Zimmermann's Knitter's Almanac. Dover Publications

- Isaacson, Steve. (2013). Carol Milne Knitted Glass - How Does She Do that? ISBN 978-1482748048

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Knitting. |

| Look up knitting in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Knitting. |

- craftyarncouncil.com, Relationship between yarn weight and knitting gauge.

- "Knitting". Fashion, Jewellery & Accessories. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- Knitting Together Business & Heritage. Living Heritage Economy Case Study 002, December 2018. Dale Gilbert Jarvis, ed.

- The Physics of "Knitting" (NYT; 17 May 2019)

- US and UK Conversion Chart Shows US and UK conversion charts, relationship to needle size and typical usage.