Kayak

A kayak is a small, narrow watercraft which is typically propelled by means of a double-bladed paddle. The word kayak originates from the Greenlandic word qajaq (IPA: [qajɑq]).

The traditional kayak has a covered deck and one or more cockpits, each seating one paddler. The cockpit is sometimes covered by a spray deck that prevents the entry of water from waves or spray, differentiating the craft from a canoe. The spray deck makes it possible for suitably skilled kayakers to roll the kayak: that is, to capsize and right it without it filling with water or ejecting the paddler.

Some modern boats vary considerably from a traditional design but still claim the title "kayak", for instance in eliminating the cockpit by seating the paddler on top of the boat ("sit-on-top" kayaks); having inflated air chambers surrounding the boat; replacing the single hull by twin hulls, and replacing paddles with other human-powered propulsion methods, such as foot-powered rotational propellers and "flippers". Kayaks are also being sailed, as well as propelled by means of small electric motors, and even by outboard gas engines.

The kayak was first used by the indigenous Aleut, Inuit, Yupik and possibly Ainu[1] hunters in subarctic regions of the world.

History

Kayaks (Inuktitut: qajaq (ᖃᔭᖅ Inuktitut pronunciation: [qaˈjaq]), Yup'ik: qayaq (from qai- "surface; top"),[2] Aleut: Iqyax) were originally developed by the Inuit, Yup'ik, and Aleut. They used the boats to hunt on inland lakes, rivers and coastal waters of the Arctic Ocean, North Atlantic, Bering Sea and North Pacific oceans. These first kayaks were constructed from stitched seal or other animal skins stretched over a wood or whalebone-skeleton frame. (Western Alaskan Natives used wood whereas the eastern Inuit used whalebone due to the treeless landscape). Kayaks are believed to be at least 4,000 years old. The oldest existing kayaks are exhibited in the North America department of the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich, with the oldest dating from 1577.[3]

Native people made many types of boats for different purposes. The Aleut baidarka was made in double or triple cockpit designs, for hunting and transporting passengers or goods. An umiak is a large open sea canoe, ranging from 17 to 30 feet (5.2 to 9.1 m), made with seal skins and wood. It is considered a kayak although it was originally paddled with single-bladed paddles, and typically had more than one paddler.

Native builders designed and built their boats based on their own experience and that of the generations before them, passed on through oral tradition. The word "kayak" means "man's boat" or "hunter's boat", and native kayaks were a personal craft, each built by the man who used it—with assistance from his wife, who sewed the skins—and closely fitting his size for maximum maneuverability. The paddler wore a tuilik, a garment that was stretched over the rim of the kayak coaming, and sealed with drawstrings at the coaming, wrists, and hood edges. This enabled the "eskimo roll" and rescue to become the preferred methods of recovery after capsizing, especially as few Inuit could swim; their waters are too cold for a swimmer to survive for long.[4]

Instead of a tuilik, most traditional kayakers today use a spray deck made of waterproof synthetic material stretchy enough to fit tightly around the cockpit rim and body of the kayaker, and which can be released rapidly from the cockpit to permit easy exit.

Inuit kayak builders had specific measurements for their boats. The length was typically three times the span of his outstretched arms. The width at the cockpit was the width of the builder's hips plus two fists (and sometimes less). The typical depth was his fist plus the outstretched thumb (hitch hiker). Thus typical dimensions were about 17 feet (5.2 m) long by 20–22 inches (51–56 cm) wide by 7 inches (18 cm) deep. This measurement system confounded early European explorers who tried to duplicate the kayak, because each kayak was a little different.

Traditional kayaks encompass three types: Baidarkas, from the Bering sea & Aleutian islands, the oldest design, whose rounded shape and numerous chines give them an almost Blimp-like appearance; West Greenland kayaks, with fewer chines and a more angular shape, with gunwales rising to a point at the bow and stern; and East Greenland kayaks that appear similar to the West Greenland style, but often fit more snugly to the paddler and possess a steeper angle between gunwale and stem, which lends maneuverability.

Most of the Aleut people in the Aleutian Islands eastward to Greenland Inuit relied on the kayak for hunting a variety of prey—primarily seals, though whales and caribou were important in some areas. Skin-on-frame kayaks are still being used for hunting by Inuit people in Greenland, because the smooth and flexible skin glides silently through the waves. In other parts of the world home builders are continuing the tradition of skin on frame kayaks, usually with modern skins of canvas or synthetic fabric, such as sc. ballistic nylon.

Contemporary traditional-style kayaks trace their origins primarily to the native boats of Alaska, northern Canada, and Southwest Greenland. The use of fabric kayaks on wooden frames, called a foldboat or folding kayak (German faltboot or Hardernkahn) became widely popular in Europe beginning in 1907 when they were mass produced by Johannes Klepper and others. This type of kayak was introduced to England and Europe by John MacGregor (sportsman) in 1860, but Klepper was the first person to mass produce these boats made of collapsible wooden frames covered by waterproof rubberized canvas. By 1929, Klepper and Company were making 90 foldboats a day. Joined by other European manufacturers, by the mid 1930s there were an estimated half million foldboat kayaks in use throughout Europe. First Nation masters of the roll taught this technique to Europeans during this time period.[6][7]

These boats were tough and intrepid individuals were soon doing amazing things in them. In June of 1928 a German named Franz Romer Sea kayak rigged his 20-foot-long foldboat with a sail and departed from Las Palmas in the Canary Islands carrying 590 pounds of tinned food and 55 gallons of water. Fifty-eight days and 2,730 miles later he reached Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. Another German, Oskar Speck, paddled his foldboat down the Danube and four years later reached the Australian coast after having traveled roughly 14,000 miles across the Pacific.[8]

These watercraft were brought to the United States and used competitively in 1940 at the first National Whitewater Championship held in America near Middledam, Maine, on the Rapid River (Maine). One “winner,” Royal Little, crossed the finish line clinging to his overturned foldboat. Upstream, the river was “strewn with many badly buffeted and some wrecked boats.” Two women were in the competition, Amy Lang and Marjory Hurd. With her partner Ken Hutchinson, Hurd won the double canoe race. Lang won the doubles foldboat event with her partner, Alexander "Zee" Grant.[9]

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Alexander “Zee” Grant was most likely America’s best foldboat pilot. Grant kayaked the Gates of Lodore on the Green River (Colorado River tributary) in Dinosaur National Monument in 1939 and the Middle Fork Salmon River in 1940. In 1941, Grant paddled a foldboat through Grand Canyon National Park. He outfitted his foldboat, named Escalante, with a sponson on each side of his boat and filled the boat with beach balls. As with nearly all American foldboat enthusiasts of the day, he did not know how to roll his boat.[10][11]

Fiberglass mixed with resin composites, invented in the 1930s and 40s, were soon used to make kayaks and this type of watercraft saw increased use during the 1950s, including in the US. Kayak Slalom World Champion Walter Kirschbaum built a fiberglass kayak and paddled it through Grand Canyon in June of 1960. He knew how to roll and only swam once, in Hance Rapid (see List of Colorado River rapids and features). Like Grant's foldboat, Kirschbaum's fiberglass kayak had no seat and no thigh braces.[12]

Inflatable rubberized fabric boats were first introduced in Europe and Rotomolded plastic kayaks first appeared in 1973. Most kayaks today are made from roto-molded polyethylene resins. The development of plastic and rubberized inflatable kayaks arguably initiated the development of freestyle kayaking as we see it today, since these boats could be made smaller, stronger and more resilient than fiberglass boats.

Design principles

Typically, kayak design is largely a matter of trade-offs: directional stability ("tracking") vs maneuverability; stability vs speed; and primary vs secondary stability. Multihull kayaks face a different set of trade-offs. The paddler's body shape and size is an integral part of the structure, and will also affect the trade-offs made.

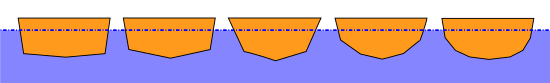

Displacement

If the displacement of a kayak is not enough to support the passenger(s) and gear, it will sink. If the displacement is excessive, the kayak will float too high, catch the wind and waves uncomfortably, and handle poorly;[13] it will probably also be bigger and heavier and than it needs to be. Being excessively big will create more drag, and the kayak will move more slowly and take more effort.[14] Rolling is easier in lower-displacement kayaks. On the other hand, a higher deck will keep the paddler(s) dryer and make self-rescue and coming through surf easier.[13] Many paddlers who use a sit-in kayak feel more secure in a kayak with a weight capacity substantially more than their own weight. Maximum volume in a sit-in kayak is helped by a wide hull with high sides. But paddling ease is helped by lower sides where the paddler sits and a narrower width.

Most manufacturers make kayaks for paddlers weighing 65–85 kg (143–187 lb), with some kayaks for paddlers down to 50 kg (110 lb).[13][15][16] Kayaks made for paddlers under 100 pounds are almost all very beamy and intended for beginners.

There seem to be no anthropometry stats of kayakers, who may not be representative of the general population. In the American civilian population of the early 1960s, about 0.7% of men and 9% of women weighed under 50 kg (110 lb); 20% of men and 7% of women weighed over 190 pounds (86 kg).[17] In the same population in the late sixties, the average weight of both male and female children crossed 50 kg (110 lb) at age thirteen. In the early 2000s, it was a year or two earlier, and the mean weight of adults was over 10 kg (22 lb) heavier. Also in the early 2000s, the mean weight of men was 190 pounds (86 kg), and the mean weight of women was 163 pounds (74 kg).[18]

Length

As a general rule, a longer kayak is faster: it has a higher hull speed. It can also be narrower for a given displacement, reducing the drag, and it will generally track (follow a straight line) better than a shorter kayak. On the other hand, it is less maneuverable. Very long kayaks are less robust, and may be harder to store and transport.[14] Some recreational kayak makers try to maximize hull volume (weight capacity) for a given length as shorter kayaks are easier to transport and store.[19][20]

Kayaks that are built to cover longer distances such as touring and sea kayaks are longer, generally 16 to 19 feet (4.88 to 5.79 m). With touring kayaks the keel is generally more defined (helping the kayaker track in a straight line). Whitewater kayaks, which generally depend upon river current for their forward motion, are short, to maximize maneuverability. These kayaks rarely exceed 8 feet (2.44 m) in length, and play boats may be only 5–6 feet (1.52–1.83 m) long. Recreational kayak designers try to provide more stability at the price of reduced speed, and compromise between tracking and maneuverability, ranging from 9–14 feet (2.74–4.27 m).

Rocker

Length alone does not fully predict a kayak's maneuverability: a second design element is rocker, i.e. its lengthwise curvature. A heavily rockered boat curves more, shortening its effective waterline. For example, an 18-foot (5.5 m) kayak with no rocker is in the water from end to end. In contrast, the bow and stern of a rockered boat are out of the water, shortening its lengthwise waterline to only 16 ft (4.9 m). Rocker is generally most evident at the ends, and in moderation improves handling. Similarly, although a rockered whitewater boat may only be a few feet shorter than a typical recreational kayak, its waterline is far shorter and its maneuverability far greater. When surfing, a heavily rockered boat is less likely to lock into the wave as the bow and stern are still above water. A boat with less rocker cuts into the wave and makes it harder to turn while surfing.

Beam profile

The overall width of a kayak's cross section is its beam. A wide hull is more stable, and packs more displacement into a shorter length. A narrow hull has less drag and is generally easier to paddle; in waves it will ride more easily and stay dryer.[14]

A narrower kayak makes a somewhat shorter paddle appropriate and a shorter paddle puts less strain on the shoulder joints. Some paddlers are comfortable with a sit-in kayak so narrow that their legs extend fairly straight out. Others want sufficient width to permit crossing their legs inside the kayak.

Types of stability

Primary (sometimes called initial) stability describes how much a boat tips, or rocks back and forth, when displaced from level by paddler weight shifts. Secondary stability describes how stable a kayak feels when put on edge or when waves are passing under the hull perpendicular to the length of the boat. For kayak rolling, tertiary stability, or the stability of an upside-down kayak, is also important (lower tertiary stability makes rolling up easier).

Primary stability is often a big concern to a beginner, while secondary stability matters both to beginners and experienced travelers. By example, a wide, flat-bottomed kayak will have high primary stability and feel very stable on flat water. However, when a steep wave breaks on such a boat, it can be easily overturned because the flat bottom is no longer level. By contrast, a kayak with a narrower, more rounded hull with more hull flare can be edged or leaned into waves and (in the hands of a skilled kayaker) provides a safer, more comfortable response on stormy seas. Kayaks with only moderate primary, but excellent secondary stability are, in general, considered more seaworthy, especially in challenging conditions.

The shape of the cross section affects stability, maneuverability, and drag. Hull shapes are categorized by roundness/flatness, and by the presence and angle of chines. This cross–section may vary along the length of the boat.

A chine typically increases secondary stability by effectively widening the beam of the boat when it heels (tips). A V-shaped hull tends to travel straight (track) well, but makes turning harder. V-shaped hulls also have the greatest secondary stability. Conversely, flat-bottomed hulls are easy to turn, but harder to direct in a constant direction. A round-bottomed boat has minimal wetter area, and thus minimizes drag; however, it may be so unstable that it will not remain upright when floating empty, and needs continual effort to keep it upright. In a skin-on-frame kayak, chine placement may be constrained by the need to avoid the bones of the pelvis.[21]

Sea kayaks, designed for open water and rough conditions, are generally narrower at 22–25 inches (56–64 cm) and have more secondary stability than recreational kayaks, which are wider 26–30 inches (66–76 cm), have a flatter hull shape, and more primary stability.

Stability from body shape and skill level

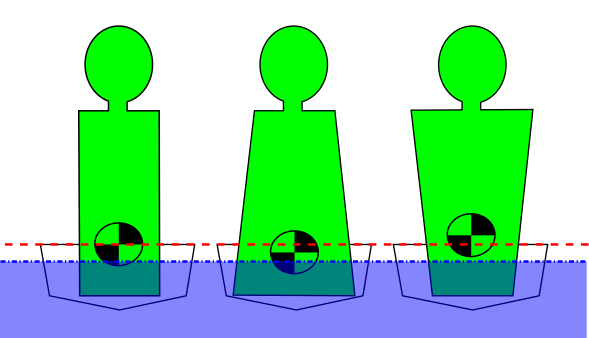

The position of the center of gravity is affected by body shape. The lower the CoG, the higher the primary stability.

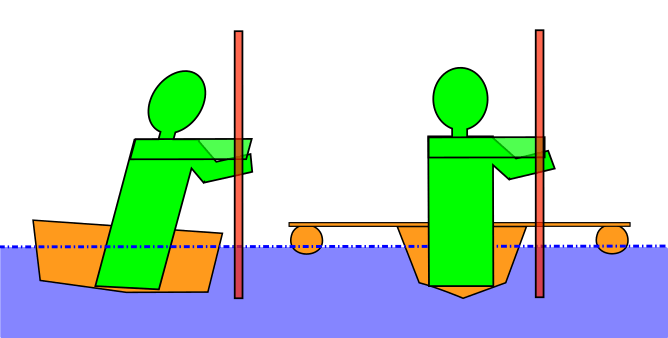

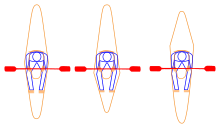

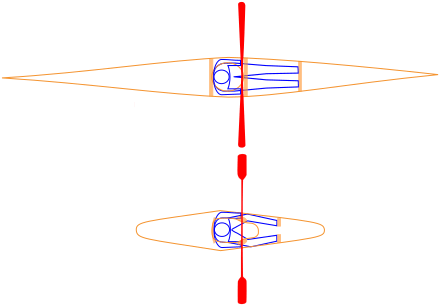

The position of the center of gravity is affected by body shape. The lower the CoG, the higher the primary stability. Two different approaches to giving beginners more stability; left, a wider kayak, right, outriggers lashed across the stern deck.

Two different approaches to giving beginners more stability; left, a wider kayak, right, outriggers lashed across the stern deck.

The body of the paddler must also be taken into account. A paddler with a low center of gravity will find all boats more stable; for a paddler with a high center of gravity, all boats will feel tippier. On average, women and children have a lower COG than men.[13][15][16] Unisex kayaks are built for men.[14] A paddler with narrow shoulders will also want a narrower kayak.

Newcomers will often want a craft with high primary stability (see above). The southern method is a wider kayak. The northern method is a removable pair of outriggers, lashed across the stern deck.[16][22] Such an outrigger pair is often homemade of a small plank and found floats such as empty bottles or plastic ducks.[23] Outriggers are also made commercially, especially for fishing kayaks and sailing. If the floats are set so that they are both in the water, they give primary stability, but produce more drag. If they are set so that they are both out of the water when the kayak is balanced, they give secondary stability.[24][25]

Hull surface profile

Some kayak hulls are categorized according to the shape from bow to stern

Common shapes include:

- Symmetrical: the widest part of the boat is halfway between bow and stern.

- Fish form: the widest part is forward (in front) of the midpoint.

- Swede form: the widest part is aft (behind) midpoint.

Seating position and contact points

Traditional-style and some modern types of kayaks (e.g. sit-on-top) require that paddler be seated with their legs stretched in front of them, in a right angle, in a position called the "L" kayaking position. Other kayaks offer a different sitting position, in which the paddler's legs are not stretched out in front of them, and the thigh brace bears more on the inside than the top of the thighs (see diagram).

A kayaker must be able to move the hull of their kayak by moving their lower body, and brace themselves against the hull (mostly with the feet) on each stroke. Most kayaks therefore have footrests and a backrest. Some kayaks fit snugly on the hips; others rely more on thigh braces. Mass-produced kayaks generally have adjustable bracing points. Many paddlers also customize their kayaks by putting in shims of closed-cell foam, or more elaborate structure, to make it fit more tightly.[26]

Paddling puts substantial force through the legs, alternately with each stroke. The knees should therefore not be hyperextended. Separately, if the kneecap is in contact with the boat, this will cause pain and may injure the knee. Insufficient foot space will cause painful cramping and inefficient paddling. The paddler should generally be in a comfortable position.

Attempting to lift and carry a kayak by oneself or improperly is a significant cause of kayaking injuries.[27] Good lifting technique, sharing loads, and not using needlessly large and heavy kayaks prevents injuries.[28]

Materials and construction

Today almost all kayaks are commercial products intended for sale rather than for the builder's personal use.

Fiberglass hulls are stiffer than polyethylene hulls, but they are more prone to damage from impact, including cracking. Most modern kayaks have steep V sections at the bow and stern, and a shallow V amidships. Fiberglass kayaks need to be "laid-up" in a mold by hand, so are usually more expensive than polyethylene kayaks, which are rotationally molded in a machine.

Plastic kayaks are rotationally molded ('rotomolded') from a various grades and types of polyethylene resins ranging from soft to hard. Such kayaks are particularly resistant to impact.

Wooden hulls don't necessarily require significant skill and handiwork, depending on how they are made. Kayaks made from thin strips of wood sheathed in fiberglass have proven successful, especially as the price of epoxy resin has decreased in recent years. A plywood, stitch and glue (S&G) doesn't need fiberglass sheathing though some builders do. Three main types are popular, especially for the home builder: Stitch & Glue, Strip-Built, and hybrids which have a stitch & glue hull and a strip-built deck.

Stitch & Glue designs typically use modern, marine-grade plywood — eighth-inch, 3 millimetres (0.12 in) or up to quarter-inch, 5 millimetres (0.20 in) thick. After cutting out the required pieces of hull and deck (kits often have these pre-cut), a series of small holes are drilled along the edges. Copper wire is then used to "stitch" the pieces together through the holes. After the pieces are temporarily stitched together, they are glued with epoxy and the seams reinforced with fiberglass. When the epoxy dries, the copper stitches are removed. Sometimes the entire boat is then covered in fiberglass for additional strength and waterproofing though this adds greatly to the weight and is unnecessary. Construction is fairly straightforward, but because plywood does not bend to form compound curves, design choices are limited. This is a good choice for the first-time kayak builder as the labor and skills required (especially for kit versions) is considerably less than for strip-built boats which can take 3 times as long to build.

Strip-built designs are similar in shape to rigid fiberglass kayaks but are generally both lighter and tougher. Like their fiberglass counterparts the shape and size of the boat determines performance and optimal uses. The hull and deck are built with thin strips of lightweight wood, often cedar, pine or Redwood. The strips are edge-glued together around a form, stapled or clamped in place, and allowed to dry. Structural strength comes from a layer of fiberglass cloth and epoxy resin, layered inside and outside the hull. Strip–built kayaks are sold commercially by a few companies, priced US$4,000 and up. An experienced woodworker can build one for about US$400 in 200 hours, though the exact cost and time depend on the builder's skill, the materials and the size and design. As a second kayak project, or for the serious builder with some woodworking expertise, a strip–built boat can be an impressive piece of work. Kits with pre-cut and milled wood strips are commercially available.

Skin on frame boats are more traditional in design, materials, and construction. They were traditionally made of driftwood, pegged or lashed together, and stretched seal skin, as those were the most readily available materials in the Arctic regions. Today, seal skin is usually replaced with canvas or nylon cloth covered with paint, polyurethane, or a hypalon rubber coating and a wooden or aluminum frame. Modern skin-on-frame kayaks often possess greater impact resistance than their fiberglass counterparts, but are less durable against abrasion or sharp objects. They are often the lightest kayaks.

A special type of skin-on-frame kayak is the folding kayak. It has a collapsible frame, of wood, aluminum or plastic, or a combination thereof, and a skin of water-resistant and durable fabric. Many types have air sponsons built into the hull, making the kayak float even if flooded.

Modern design

Modern kayaks differ greatly from native kayaks in every aspect—from initial form through conception, design, manufacturing and usage. Modern kayaks are designed with computer-aided design (CAD) software, often in combination with CAD customized for naval design.

Modern kayaks serve diverse purposes, ranging from slow and easy touring on placid water, to racing and complex maneuvering in fast-moving whitewater, to fishing and long-distance ocean excursions. Modern forms, materials and construction techniques make it possible to effectively serve these needs while continuing to leverage the insights of the original Arctic inventors.

Kayaks are long—19 feet (5.8 m), short—6 feet (1.8 m), wide—42 inches (110 cm), or as narrow as the paddler's hips. They may attach one or two stabilizing hulls (outriggers), have twin hulls like catamarans, inflate or fold. They move via paddles, pedals that turn propellers or underwater flippers, under sail, or motor. They're made of wood/canvas, wood, carbon fiber, fiberglass, Kevlar, polyethylene, polyester, rubberized fabric, neoprene, nitrylon, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane, and aluminum. They may sport rudders, fins, bulkheads, seats, eyelets, foot braces and cargo hatches. They accommodate 1-3 or more paddlers/riders.

Types

| Major Kayak Types |

|---|

| Sea Kayak |

| Whitewater kayak |

| Recreational kayak |

| Racing kayak |

Modern kayaks have evolved into specialized types that may be broadly categorized according to their application as sea or touring kayaks, whitewater (or river) kayaks, surf kayaks, racing kayaks, fishing kayaks, and recreational kayaks. The broader kayak categories today are 'Sit-In', which is inspired mainly by traditional kayak forms, 'Sit-On-Top' (SOT), which evolved from paddle boards that were outfitted with footrests and a backrest, 'Hybrid', which are essentially canoes featuring a narrower beam and a reduced free board enabling the paddler to propel them from the middle of the boat, using a double blade paddle (i.e. 'kayak paddle'), and twin hull kayaks offering each of the paddler's legs a narrow hull of its own. In recent decades, kayaks design have proliferated to a point where the only broadly accepted denominator for them is their being designed mainly for paddling using a kayak paddle featuring two blades i.e. 'kayak paddle'. However, even this inclusive definition is being challenged by other means of human powered propulsion, such as foot activated pedal drives combined with rotating or sideways moving propellers, electric motors, and even outboard motors.

Recreational

Recreational kayaks are designed for the casual paddler interested in fishing, photography, or a peaceful paddle on a lake, flatwater stream or protected salt water away from strong ocean waves. These boats presently make up the largest segment of kayak sales. Compared to other kayaks, recreational kayaks have a larger cockpit for easier entry and exit and a wider beam (27–36 inches (69–91 cm)) for more stability. They are generally less than 12 feet (3.7 m) in length and have limited cargo capacity. Less expensive materials like polyethylene and fewer options keep these boats relatively inexpensive. Most canoe/kayak clubs offer introductory instruction in recreational boats. They do not perform as well in the sea. The recreational kayak is usually a type of touring kayak.

Sea

Sea kayaks are typically designed for travel by one, two or even three paddlers on open water and in many cases trade maneuverability for seaworthiness, stability, and cargo capacity. Sea-kayak sub-types include "skin-on-frame" kayaks with traditionally constructed frames, open-deck "sit-on-top" kayaks, and recreational kayaks.

The sea kayak, though descended directly from traditional types, is implemented in a variety of materials. Sea kayaks typically have a longer waterline, and provisions for below-deck storage of cargo. Sea kayaks may also have rudders or skegs (fixed rudder) and upturned bow or stern profiles for wave shedding. Modern sea kayaks usually have two or more internal bulkheads. Some models can accommodate two or sometimes three paddlers.

Sit-on-top

Sealed-hull (unsinkable) craft were developed for leisure use, as derivatives of surfboards (e.g. paddle or wave skis), or for surf conditions. Variants include planing surf craft, touring kayaks, and sea marathon kayaks. Increasingly, manufacturers build leisure 'sit-on-top' variants of extreme sports craft, typically using polyethylene to ensure strength and affordability, often with a skeg for directional stability. Water that enters the cockpit drains out through scupper holes—tubes that run from the cockpit to the bottom of the hull.

Sit-on-top kayaks come in 1-4 paddler configurations. Sit-on-top kayaks are particularly popular for fishing and SCUBA diving, since participants need to easily enter and exit the water, change seating positions, and access hatches and storage wells. Ordinarily the seat of a sit-on-top is slightly above water level, so the center of gravity for the paddler is higher than in a traditional kayak. To compensate for the higher center of gravity, sit-on-tops are often wider and slower than a traditional kayak of the same length.

Contrary to popular belief, the sit-on-top kayak hull is not self bailing, since water penetrating it does not drain out automatically, as it does in bigger boats equipped with self bailing systems. Furthermore, the sit-on-top hull cannot be molded in a way that would assure water tightness, and water may get in through various holes in its hull, usually around hatches and deck accessories. If the sit-on-top kayak is loaded to a point where such perforations are covered with water, or if the water paddled is rough enough that such perforations often go under water, the sit-on-top hull may fill with water without the paddler noticing it in time.

Surf

Specialty surf boats typically have flat bottoms, and hard edges, similar to surf boards. The design of a surf kayak promotes the use of an ocean surf wave (moving wave) as opposed to a river or feature wave (moving water). They are typically made from rotomolded plastic, or fiberglass.

Surf kayaking comes in two main varieties, High Performance (HP) and International Class (IC). HP boats tend to have a lot of nose rocker, little to no tail rocker, flat hulls, sharp rails and up to four fins set up as either a three fin thruster or a quad fin. This enables them to move at high speed and maneuver dynamically. IC boats have to be at least 3 metres (9.8 ft) long and until a recent rule change had to have a convex hull; now flat and slightly concave hulls are also allowed, although fins are not. Surfing on international boats tends to be smoother and more flowing, and they are thought of as kayaking's long boarding. Surf boats come in a variety of materials ranging from tough but heavy plastics to super light, super stiff but fragile foam–cored carbon fiber. Surf kayaking has become popular in traditional surfing locations, as well as new locations such as the Great Lakes.

Waveskis

A variation on the closed cockpit surf kayak is called a waveski. Although the waveski offers dynamics similar to a sit–on–top, its paddling technique and surfing performance and construction can be similar to surfboard designs.

Whitewater

Whitewater kayaks are rotomolded in a semi-rigid, high impact plastic, usually polyethylene. Careful construction ensures that the boat remains structurally sound when subjected to fast-moving water. The plastic hull allows these kayaks to bounce off rocks without leaking, although they scratch and eventually puncture with enough use. Whitewater kayaks range from 4 to 10 feet (1.2 to 3.0 m) long. There are two main types of whitewater kayak:

Playboat

One type, the playboat, is short, with a scooped bow and blunt stern. These trade speed and stability for high maneuverability. Their primary use is performing tricks in individual water features or short stretches of river. In playboating or freestyle competition (also known as rodeo boating), kayakers exploit the complex currents of rapids to execute a series of tricks, which are scored for skill and style.

Creekboat

The other primary type is the creek boat, which gets its name from its purpose: running narrow, low-volume waterways. Creekboats are longer and have far more volume than playboats, which makes them more stable, faster and higher-floating. Many paddlers use creekboats in "short boat" downriver races, and they are often seen on large rivers where their extra stability and speed may be necessary to get through rapids.

Between the creekboat and playboat extremes is a category called river–running kayaks. These medium–sized boats are designed for rivers of moderate to high volume, and some, known as river running playboats, are capable of basic playboating moves. They are typically owned by paddlers who do not have enough whitewater involvement to warrant the purchase of more–specialized boats.

Squirt Boating involves paddling both on the surface of the river and underwater. Squirt boats must be custom-fitted to the paddler to ensure comfort while maintaining the low interior volume necessary to allow the paddler to submerge completely in the river.

Racing

Whitewater

White water racers combine a fast, unstable lower hull portion with a flared upper hull portion to combine flat water racing speed with extra stability in open water: they are not fitted with rudders and have similar maneuverability to flat water racers. They usually require substantial skill to achieve stability, due to extremely narrow hulls. Whitewater racing kayaks, like all racing kayaks, are made to regulation lengths, usually of fiber reinforced resin (usually epoxy or polyester reinforced with Kevlar, glass fiber, carbon fiber, or some combination). This form of construction is stiffer and has a harder skin than non-reinforced plastic construction such as rotomolded polyethylene: stiffer means faster, and harder means fewer scratches and therefore also faster.

Flatwater sprint

Sprint kayak is a sport held on calm water. Crews or individuals race over 200 m, 500 m, 1000 m or 5000 m with the winning boat being the first to cross the finish line. The paddler is seated, facing forward, and uses a double-bladed paddle pulling the blade through the water on alternate sides to propel the boat forward. In competition the number of paddlers within a boat is indicated by a figure besides the type of boat; K1 signifies an individual kayak race, K2 pairs, and K4 four-person crews. Kayak sprint has been in every summer olympics since it debuted at the 1936 summer olympics.[29] Racing is governed by the International Canoe Federation.

Slalom

Slalom kayaks are flat–hulled, and—since the early 1970s—feature low profile decks. They are highly maneuverable, and stable but not fast in a straight line.

Surf ski

A specialized variant of racing craft called a surf ski has an open cockpit and can be up to 21 feet (6.4 m) long but only 18 inches (46 cm) wide, requiring expert balance and paddling skill. Surf skis were originally created for surf and are still used in races in New Zealand, Australia, and South Africa. They have become popular in the United States for ocean races, lake races and even downriver races.

Marathon

Marathon races vary in distances from ten kilometres to over 1000 kilometres for multi-day stage races.

Specialty and hybrids

The term "kayak" is increasingly applied to craft that look little like traditional kayaks.

Inflatable

Inflatables, also known as the duckies or IKs, can usually be transported by hand using a carry bag. They are generally made of hypalon (a kind of neoprene), Nytrylon (a rubberized fabric), PVC, or polyurethane coated cloth. They can be inflated with foot, hand or electric pumps. Multiple compartments in all but the least expensive increase safety. They generally use low pressure air, almost always below 3 psi.

While many inflatables are non-rigid, essentially pointed rafts, best suited for use on rivers and calm water, the higher end inflatables are designed to be hardy, seaworthy vessels. Recently some manufacturers have added an internal frame (folding-style) to a multi-section inflatable sit-on-top kayak to produce a seaworthy boat.

The appeal of inflatable kayaks is their portability, their durability (they don't dent), ruggedness in white water (they bounce off rocks rather than break) and their easy storage. In addition, inflatable kayaks generally are stable, have a small turning radius and are easy to master, although some models take more effort to paddle and are slower than traditional kayaks.

Because inflatable kayaks aren't as sturdy as traditional, hard-shelled kayaks, a lot of people tend to steer away from them. However, there have been considerable advancements in inflatable kayak technology over recent years.

Folding

Folding kayaks are direct descendants of the skin-on-frame boats used by the Inuit and Greenlandic peoples. Modern folding kayaks are constructed from a wooden or aluminum frame over which is placed a synthetic skin made of polyester, cotton canvas, polyurethane, or Hypalon. They are more expensive than inflatable kayaks, but have the advantage of greater stiffness and consequently better seaworthiness.

Walter Höhn (English Hoehn) had built, developed and then tested his design for a folding kayak in the white-water rivers of Switzerland from 1924 to 1927. In 1928, on emigrating to Australia, he brought 2 of them with him, lodged a patent for the design and proceeded to manufacture them. In 1942 the Australian Director of Military operations approached him to develop them for Military use. Orders were placed and eventually a total of 1024, notably the MKII & MKIII models, were produced by him and another enterprise, based on his 1942 patent (No. 117779)[30]

Pedal

A kayak with pedals allows the kayaker to propel the vessel with a rotating propeller or underwater "flippers" rather than with a paddle. In contrast to paddling, kayakers who pedal kayaks use their legs rather than their arms.

Twin hull and outrigger

Traditional multi-hull vessels such as catamarans and outrigger canoes benefit from increased lateral stability without sacrificing speed, and these advantages have been successfully applied in twin hull kayaks. Outrigger kayaks attach one or two smaller hulls to the main hull to enhance stability, especially for fishing, touring, kayak sailing and motorized kayaking. Twin hull kayaks feature two long and narrow hulls, and since all their buoyancy is distributed as far as possible from their center line, they are stabler than mono hull kayaks outfitted with outriggers.

Fishing

While native people of the Arctic regions hunted rather than fished from kayaks, in recent years kayak sport fishing has become popular in both fresh and salt water, especially in warmer regions. Traditional fishing kayaks are characterized by wide beams of up to 42 inches (110 cm) that increase their lateral stability. Some are equipped with outriggers that increase their stability, and others feature twin hulls enabling stand up paddling and fishing. Compared with motorboats, fishing kayaks are inexpensive and have few maintenance costs. Many kayak anglers like to customize their kayaks for fishing, a process known as 'rigging'.

Military

Kayaks were adapted for military use in the Second World War. Used mainly by British Commando and special forces, principally the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties (COPPs), the Special Boat Service and the Royal Marines Boom Patrol Detachment. The latter made perhaps the best known use of them in the Operation Frankton raid on Bordeaux harbor.[31] Both the Special Air Service (SAS) and the Special Boat Service (SBS) used kayaks for reconnaissance in the 1982 Falklands War.[32] US Navy SEALs reportedly used them at the start of Unified Task Force operations in Somalia in 1992.[33] The SBS currently use Klepper two-man folding kayaks that can be launched from surfaced submarines or carried to the surface by divers from submerged ones. They can be parachuted from transport aircraft into the ocean or dropped from the back of Chinook helicopters.[34] US Special Forces have used Kleppers but now primarily use Long Haul folding kayaks, which are made in the US.[35]

The Australian Military MKII and MKIII folding kayaks were extensively used during the 1941-1945 Pacific War for some 33 raids and missions on and around the South-East Asian islands. Documentation for this will be found in the National Archives of Australia official records, reference No. NAA K1214-123/1/06. They were deployed from disguised watercraft, submarines, Catalina aircraft, P.T. boats, motor launches and by parachute.[36]

See also

- Aleutian kayak

- Boat

- Canoe

- Canoe & Kayak UK

- Canoe polo

- Canyoning

- Creeking

- Flyak

- Freeboating

- Kayak angst

- Kayak fishing

- Kayaking

- Playboating

- Recreational kayak

- Sea kayaking

- Squirt boating

- Surf kayaking

- Umiak

- Waveski

- Whitewater slalom

References

- There is scant evidence of Ainu peoples using the classic kayak design in prehistoric times. The following indicates that they did use skin-covered vessels, however: "Like the yara chisei, bark houses, … yara chip, bark boats, were probably substitutes for the skin-covered boat, elsewhere surviving in the coracle and kayak. Skin-covered boats … are referred to in old [Ainu] traditions. -Ainu material culture from the notes of N. G. Munro: in the archive of the Royal Anthropological Institute, British Museum, Department of Ethnography, 1994, p. 33

- Jacobson, Steven A. (2012). Yup'ik Eskimo Dictionary, 2nd edition. Alaska Native Language Center.

- (in English) Voelkerkundemuseum-muenchen.de Archived 2008-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- D.C. Hutchinson, "The Complete Book of Sea Kayaking", 5th ed., Falcon Guides, Connecticut.

- http://www.qajaqusa.org/QK/makegreen2.pdf

- Altenhofer, Der Hadernkahn, Pollner Verlag, 1997, pg 143, ISBN 3925660097

- Dyson, Baidarka, Alaska Northwest Publishing Company, 1986, p 80-81, ISBN 978-0882403151

- “Renew Attempt To Row Boat Across Atlantic,” Messenger Inquirer, April 23, 1928; “In A Rubber Boat Over The Sea,” Baltimore Sun, September 30, 1928; “Rowing Around World In A Canvas Boat,” Bradford Evening Star, November 13, 1935

- “Only Three Shoot Rapids,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 7, 1940

- Cockleshell on the Colorado, American Whitewater Vol 4, No 2, p 6-13, P2P p 426

- “How It Feels To Run Treacherous Rapids Of Colorado River Related By Altadenan,” Pasadena Post, July 28, 1941><ref Marston, From Powell to Power, Vishnutemple Press, 2014, p 424, ISBN 9780990527022

- Martin, Big Water Little Boats, Vishnu Temple Press, 2012, pg. 190, ISBN 9780979505560

- "Kayarchy - the kayak". kayarchy.com.

- "Kayarchy - sea kayak design". kayarchy.com.

- "Kayarchy - retail outlets (3) sea kayaks & paddles". kayarchy.com.

- "Kayarchy - sea kayaking for kids". kayarchy.com.

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_11/sr11_014acc.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ad/ad347.pdf

- "Car-Topping and Strapping Down a Kayak". Kayak Roof Racks. 2016-05-14. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- "How to Store a Kayak". wikiHow. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- "kayakways.net - Kayak Fitting". www.kayakways.net.

- "Championships". www.traditionalkayaks.com.

- "Greenland National Championships in Sisimiut 2006".

- "Hobie Gear SideKick AMA Kit Hobie Kayak Outrigger".

- "Outriggers – Wavewalk® Stable Fishing Kayaks, Portable Boats and Skiffs".

- Crowhurst, Christopher (25 September 2012). "Masik designs for modern kayaks". Qajaq Rolls.

- "Kayarchy - contents of chapter on sea kayaking safety". kayarchy.com.

- "Kayarchy - paddling your sea kayak (1) starting out". kayarchy.com.

- "ICF - Canoe Sprint". International Canoe Federation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- Commando Kayak 2011, ISBN 978-3-033-01717-7

- Tweedie, Neil (2010-10-28). "Cockleshell Heroes: the truth at last". Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- James D. Ladd, SBS, The Invisible Raiders: the History of the Special Boat Squadron from World War Two to the Present, Arms & Armour Press 1983, ISBN 978-0-85368-593-7 (p.231)

- "Canada's special forces to get ancient war-fighting machines: canoes - The Star". thestar.com.

- "specialboatservice.co.uk". www.specialboatservice.co.uk.

- "Kayaks | Canoes | Special Operations Forces". www.americanspecialops.com. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- Commando Kayak, Hoehn, 2011.

- Hoehn, John (2011). Commando Kayak: The Role of the Folboat in the Pacific War. Zurich, Switzerland: Hirsch Publishing. ISBN 978-3-033-01717-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Look up kayak in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kayak. |

- International Canoe Federation The International federation of kayak and canoe bodies

- The Canadian Museum of Civilization – Native Watercraft in Canada

- British Canoe Union The National Governing Body of Kayaking in the UK

- USA Canoe and Kayak The National Governing Body of Kayaking in the U.S.

- Greenlandinc terms for the parts of a kayak