Roadster (bicycle)

A roadster bicycle[1] is a type of utility bicycle once common worldwide, and still common in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and some parts of Europe. During the past few decades, traditionally styled roadster bicycles have regained popularity in the Western world, particularly as a lifestyle or fashion statement in an urban environment.[2]

Design and variants

There were three basic variants of the roadster.

Roadster

Gents' roadster

The classic gents' roadster, AKA the English roadster, has a lugged brazed steel diamond frame, rod-actuated brakes and of late, cable operated drum brake systems have been widely produced for the European market, upright North Road handlebars, a single gear ratio or 3 or 5 speed hub gears, a chaincase, steel mudguards, steel cranks, 28 x 1½ inch (ISO 635) wheels, Westwood rims, and often a Sturmey-Archer hub dynamo. Roadsters are built for durability above all else and no serious attempt is made to save weight in their design or construction, roadsters weigh upwards of 40-45 pounds (18–20 kg). They were often the mounts of policemen and rural letter carriers.[3] A derivative of the roadster, the ladies' model, is seldom called a roadster.

The roadster is very similar in design and intended use as the European city bike, a model still used in Germany, Denmark and, most notably, the Netherlands (see below). The primary differences are that the continental bicycles tend to have a higher handlebar position for a more upright riding posture, and are more likely to have rod-actuated drum brakes.

Ladies' roadster

The ladies' version of the roadster's design was very much in place by the 1890s. It had a step-through frame rather than the diamond frame of the gentlemen's model so that ladies, with their dresses and skirts, could easily mount and ride their bicycles, and commonly came with a skirt guard to prevent skirts and dresses becoming entangled in the rear wheel and spokes. As with the gents' roadster, the frame was of steel construction and the positioning of the frame and handlebars gave the rider a very upright riding position. Though they originally came with front spoon-brakes, technological advancements meant that later models were equipped with the much-improved coaster brakes or rod-actuated rim or drum-brakes.

Though the ladies' version of the roadster largely fell out of fashion in England and many other Western nations as the 20th century progressed, it continuously remained popular in the Netherlands right to the present day. The Omafiets as it is known, is a national icon, and is even used by men in the Netherlands;[4] this is why some people refer to bicycles of this design as Dutch bikes. In the Dutch language the name of these bicycles is Omafiets ("grandma bike") a term which has been in use since the 1970s.[5] However, in Frisia they often call them Widdofyts (West Frisian for "widow's bike"). The classic Omafiets is still in production in the Netherlands and has changed little since 1911:[6] it comes with a single-speed gear, 28 x 1½ (ISO 635) wheels, black painted frame and mudguards (with white-blazoning at the back of the rear one), and a rear skirt guard. Modern variants, be they painted in other colours, with aluminium frames, drum-brakes or multiple gear ratios in a hub gearing system, will all conform to the same basic look and dimensions as the classic Omafiets. The Dutch gentlemen's equivalent is called the Opafiets (Dutch for "grandpa bike") or Stadsfiets ("city bike") and generally has the same characteristics but with a "diamond" or "gents'" frame, thereby much the same as the gentleman's roadster in England and elsewhere.

Sports Roadster

A variation on this type of bicycle is the sports roadster (also known as the "light roadster"), which typically has a lighter frame, and a slightly steeper seat-tube and head-tube angle of about 70° to 72° degrees, fitted with cable brakes, comfortable "flat" North Road handlebars, mudguards and, as often as not, three, four or five-speed internal hub gears. Sports or light roadsters were fitted with 26 x 1⅜ inch (ISO 590) traditional English size wheels with Endrick rims, hence a lower bottom bracket and correspondingly lower stand-over height and weighing around 35-40 pounds (16 – 18 kg).[7] It was these bikes that were wrongly called "English racer" in the United States.[3][8]

Club Sports

Club sports, or semi-racer, bicycles were the high-performance machines of their time and place, named so as they were the style of bicycle popular with members of the many active cycling clubs. A club bicycle would typically have Reynolds 531 frame tubing, a narrow, unsprung leather saddle, inverted North Road handlebars (or drop bars), steel "rat trap" pedals with toe clips, 5-15 speed derailleur gearing, alloy rims and light high-pressure 26 x 1¼ (ISO 597) or 27 x 1¼ (ISO 630) tires. Some club bicycles would be likely to have a more exotic Sturmey-Archer hub, perhaps, a medium- or close-ratio model, 3 or 4 speed, with a very few even being equipped with the rare ASC 3-speed fixed-gear hub. Many club bicycles were single-speed machines, usually with a reversible hub: single-speed freewheel on one side, fixed-gear on the other. Derailers began to be used on this type of bicycle starting in the early '40s. Although primarily intended for fast group rides, club bicycles were also commonly used for touring as well as for time-trialing.[3][8]

History

From the early 20th century until after World War II, the roadster constituted most adult bicycles sold in the United Kingdom and in many parts of the British Empire. For many years after the advent of the motorcycle and automobile, they remained a primary means of adult transport. Major manufacturers in England were Raleigh and BSA, though Carlton, Phillips, Triumph, Rudge-Whitworth, Hercules, and Elswick Hopper also made them.

In the United States, the sports roadster was imported after World War II, and was known as the "English racer". It quickly became popular with adult cyclists seeking an alternative to the traditional youth-oriented cruiser bicycle.[7][9] While the English racer was no racing bike, it was faster and better for climbing hills than the cruiser, thanks to its lighter weight, tall wheels, narrow tires, and internally geared rear hubs.[7] In the late 1950s, U.S. manufacturers such as Schwinn began producing their own "lightweight" version of the English racer.[7]

In Britain, the utility roadster declined noticeably in popularity during the early 1970s, as a boom in recreational cycling caused manufacturers to concentrate on lightweight (10–14 kg (23–30 lb)), affordable derailleur sport bikes, actually slightly-modified versions of the racing bicycle of the era.[10]

In the 1980s, U.K. cyclists began to shift from road-only bicycles to all-terrain models such as the mountain bike.[10] The mountain bike's sturdy frame and load-carrying ability gave it additional versatility as a utility bike, usurping the role previously filled by the roadster. By 1990, the roadster was almost dead; while annual U.K. bicycle sales reached an all-time record of 2.8 million, almost all of them were mountain and road/sport models.[10]

A different situation, however, occurred and still occurs in most Asian countries as of 2014. Roadsters are still widely made and used in countries such as China, India, Pakistan, Thailand, Vietnam and others. Some of the most significant roadster manufacturers are: Flying Pigeon, Hero Cycles, Eastman Industries and Sohrab Cycles.

Roadsters in contemporary society

In much of the world, the roadster is still the standard bicycle used for daily transportation. Mass-produced in Asia, they are exported in huge numbers (mainly from India, China, and Taiwan) to developing nations as far afield as Africa and Latin America. India's Hero Cycles and Eastman Industries are still two of the world's leading roadster manufacturers, while China's Flying Pigeon was the single most popular vehicle in worldwide use.[11] Due to their relative affordability, the strength and durability of steel frames and forks and their ability to be repaired by welding, and the ability of these bicycles to carry heavy payloads, the roadster is generally by far the most common bicycle in use in developing nations, with a particular importance for those in rural areas. In parts of East Africa, the roadster is called the Black Mamba, where it is used as a taxi by enterprising cyclist/drivers, called boda-boda. Black Mambas are often repaired, customized, and manufactured locally for low costs. To further reduce costs of the Black Mamba, engineers have begun to test 3D printed bike parts that meet CEN standards.[12]

Traditional roadster models became largely obsolete in the English-speaking world and other parts of the Western world after the 1950s with the noticeable exceptions of the Netherlands and to a much lesser extent Belgium along with other parts of north-western Europe. However, they are now becoming popular once more in many of those countries that they had largely disappeared from, due to the resurgence in the bicycle as local city transport where the roadster is ideally suited due to its upright riding position, ability to carry shopping loads, simplicity and low maintenance.

In the United Kingdom, there are a number of bicycle manufacturers (such as Pashley Cycles) which make updated versions of the classic roadster and many more are imported from the continent, such as those from Dutch manufacturers such as Royal Dutch Gazelle. They are popular as student transport at universities, especially at Cambridge and Oxford, and are increasingly seen in other British cities, including London. In Australia, there has also been an increase in roadster use, particularly in Melbourne, alongside the growth of local bicycle companies such as Papillionaire[13] or Lekker, and many second-hand ones from the 1950s and 60s are being discovered and restored.[14]

Gallery

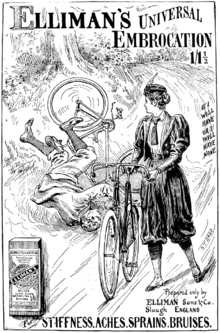

A British ad from 1897 showing a ladies' bicycle/roadster

A British ad from 1897 showing a ladies' bicycle/roadster Gentleman on a 1920s roadster, Germany

Gentleman on a 1920s roadster, Germany The roadster is known in East Africa as the "Black Mamba"

The roadster is known in East Africa as the "Black Mamba" Farmer on roadster bicycle used for freight in Indonesia

Farmer on roadster bicycle used for freight in Indonesia An opafiets or stadsfiets, is a traditional Dutch gent's roadster

An opafiets or stadsfiets, is a traditional Dutch gent's roadster A 2012 Sohrab roadster manufactured in Pakistan

A 2012 Sohrab roadster manufactured in Pakistan Modern Batavus roadster with Nexus hub and roller brake

Modern Batavus roadster with Nexus hub and roller brake

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roadster (bicycle). |

References

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 03 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Raleigh Roadsters". Sheldon Brown sheldonbrown.com. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- "Servicing English Three Speeds". Sheldon Brown sheldonbrown.com. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- De stang van de herenfiets blijkt een gevoelige kwestie

- "Damesframes". rijwiel.net (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Carlton Reid (19 August 2013). "The Dutch bike isn't Dutch it's English (and proudly not updated since 1911)". Roads Were Not Built For Cars. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- Susan Weaver (1998). A Woman's Guide to Cycling (rev. ed.). Berkeley: Ten Speed Press. p. 58. ISBN 0-89815-982-2.

- Roger St. Pierre (2009). The Book of the Bicycle. London: Triune Books. pp. 16–19. ISBN 0-85674-016-0.

- Richard Ballantine (2000). The 21st Century Bicycle Book. New York: Overlook Press. p. 22.

- Richard Ballantine (2000). The 21st Century Bicycle Book. New York: Overlook Press. p. 23.

Sales of sport and road racing bikes constituted the major part of new bike sales from 1972, when annual U.K. sales went from just 700,000 per year to 1.6 million per year in 1980.

- Dan Koeppel. "Flight of the Pigeon". Bicycling.com. Bicycling. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- Tanikella, Nagendra G.; Savonen, Benjamin; Gershenson, John; Pearce, Joshua M. (30 May 2017). "Viability of Distributed Manufacturing of Bicycle Components with 3-D Printing: CEN Standardized Polylactic Acid Pedal Testing". Journal of Humanitarian Engineering. 5 (1). ISSN 2200-4904.

- "Vintage Dutch Style City Bikes - Custom Bicycles". Papillionaire Bikes. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- "Towards Sustainable Transport: Bicycle Policy". STCWA website. Sustainable Transport Coalition of Western Australia. Archived from the original (MS-Word) on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

External links

| Look up roadster in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Sharp, Archibald (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 913–917.