Invalid carriage

Invalid carriages were usually single seater road vehicles, buggies, or self-propelled vehicles for disabled people. They pre-dated the electric mobility scooters and from the 1920s were generally powered by a small gasoline/petrol engine, although some were battery powered. They were usually designed without foot-operated controls.

History

Origins

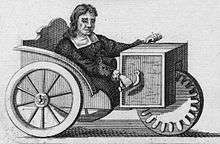

Stephan Farffler was a Nuremberg watchmaker of the seventeenth century whose invention of a manumotive carriage in 1655 is widely considered to have been the first self-propelled wheelchair. He is believed to have been either a paraplegic[1][2] or an amputee. [3] As such, the chair was consistent with the later designs for self-propelled invalid carriages. The three-wheeled device is also believed to have been a precursor to the modern-day tricycle and bicycle.[4]

In England the fore-runner of the invalid carriage was the bath chair. It was invented by James Heath, of Bath in the early 18th century.[5] Animal drawn versions of the bath chair became known as invalid carriages. An 1880 Monk and Co invalids carriage is on display at the M Shed Bristol.[6]

Between the wars

1920s Rotary invalids tricycle

1920s Rotary invalids tricycle 1930s Harding's electric powered

1930s Harding's electric powered Harding's Pultney

Harding's Pultney

Stanley Engineering Co Ltd of Egham, Surrey, began making self-propelled invalid carriages under the 'Argson' name in the 1920s. The Argson Runnymede was designed in South Africa manufactured in England from 1936 to 1954. They were either battery-powered or had a Villiers petrol engine. A petrol powered Runnymede drove across the Alps in 1947. Stanley Engineering was bought by C B Harper Ltd in 1954.[7]

R A Harding Company of Bath was founded in 1921. They initially produced hand-propelled tricycles. In 1926 Harding's introduced a variety of powered invalid carriages. The De Luxe models A and B were powered by a 122cc Villier-and the Pultney was powered by either a 200cc or 300cc JAP. There were also 24-volt or 36-volt electric machines. In 1945, the company was renamed R A Harding (Bath) Ltd, and the Pultney was discontinued. In December 1948 the De Luxe models were upgraded with larger rear wheels, a new petrol tank, and a fan-cooled Villiers 147cc unit. Hardings introduced a full bodied model in 1956 called the Consort. Only 12 of these were made. The company closed down in 1988 having made hand powered models until 1973 and motor drive ones until 1966.[8]

From the 1930s to late 1940s, Nelco Industries made a three-wheeled battery powered vehicle. Steering was by means of a tiller connected to the front wheel. The tiller also provided speed control. Forward or reverse by a separate control. The 24 volt electric motor could act as a generator to recharge the battery when going downhill. The motor was 24 volt.[9]

United Kingdom Ministry of Health contracts (1948-1978)

.jpg) AC model 57

AC model 57- 1956 Vernon Industries Gordon

- 1973 Invacar

Thundersley

Thundersley- Tippen Delta

In 1948, Bert Greeves adapted a motorcycle with the help of his paralysed cousin Derry Preston-Cobb as transport for Preston-Cobb. Noticing the number of former servicemen injured in the Second World War they spotted a commercial opportunity and approached the UK government for support, leading to the creation of Invacar Ltd.[10] Invacar was not the only company to be contracted by the Ministry of Health to produce three-wheeled vehicles for disabled drivers. Others included Harding, Dingwall & Son, AC Cars, Barrett, Tippen & Son, Thundersley, Vernon Industries, and Coventry Climax.[10][11]

These early vehicles were powered by an air-cooled Villiers 147 cc engine, but when production of that engine ceased in the early 1970s it was replaced by a much more powerful 4-stroke 500 cc or 600 cc Steyr-Puch engine, giving a reported top speed of 82 mph (132 km/h).[10] They were low-cost low-maintenance vehicles, designed specifically for people with physical disabilities. Production of them stopped in 1976, and the last were withdrawn from the road in 2003, though some still exist and approximately 25 Invacars survive that could become roadworthy once again. There are at least 5 Invacars in private ownership which are road legal and several other un-roadworthy examples which are awaiting their demise, one in the Coventry Transport Museum collection, two in the Lakeland museum in Cumbria, one road-going example "TWC" features on the HubNut YouTube channel. Another 1976 example, one of the last made, can be found on display at the National Motor Museum, Beaulieu in Hampshire, England.[12]

In Britain in the 1960s and 1970s, invalid carriages were provided as a subsidised low-cost vehicle to aid mobility of people with disabilities. Vehicles supplied by the National Health Service had 3 wheels, were very lightweight, and therefore their suitability on roads among other traffic was often considered dubious on safety grounds. Invalid-carriages are banned from motorways.[13]

Other countries

- Fend Flitzer 101

- 1956 Meyra Model E37

_2007-02-12.jpg) Simson DUO

Simson DUO_1X7A8078.jpg) SMZ S3A-M

SMZ S3A-M Velorex Oskar 54

Velorex Oskar 54

Fritz Fend, a former technical officer with the Luftwaffe, also designed a three-wheel invalid carriage in 1948. The first version was unpowered with the single wheel at the front. His powered version had a 38cc Victoria (motorcycle) two-stroke engine chain driving a single rear wheel with the pair of wheels at the front for steering. It was called the Fend Fritzer. Some 250 were made between 1948 and 1951 when it ceased production.[14]

Invalid carriages were also made in other countries: Simson DUO in East Germany,[15] SMZ in the Soviet Union and Velorex in Czechoslovakia.[16][17]

The Duo was made initially by VEB Fahrzeugbau und Ausrüstungen Brandis (VEB FAB) from 1973 until 1978, whereupon manufacture was transferred to VEB Robur, more famous for making trucks in Zittau. Because many of the components are common with the Simson, the Duo is often classified as a Simson. Production ceased in 1989.

See also

Literature

- An Introduction to the British Invalid Carriage 1850 - 1978, Stuart Cyphus, Museum of Disability History, ISBN 9780984598380

References

- Jane Bidder, Inventions We Use to Go Places (London: Franklin Watts, 2006, 18)

- Rory A. Cooper, Hisaichi Ohnabe, and Douglas A. Hobson, An Introduction to Rehabilitation Engineering (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2007, 131

- Clive Richardson, Driving, the development and use of horse-drawn vehicles (B. T. Batsford, 1985, 136)

- "Medical Innovations - Wheelchair," Science Reporter, Volume 44, 2007, 397.

- Bath chair Archived May 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. City of Bath England.

- http://www.thecarriagefoundation.org.uk/item/invalid-carriage-bristol Carriages of Britain Carriage Foundation

- Lot 500 1946 Argson Runnymede Invalid Carriage Registration no. KPK 117

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/26237061@N07/6261815278 retrieved 14 July 2018

- Nelco Solocar; Nelco Industries England; 1930s; 2008-20

- Payne, Elvis, "Invacar", 3-wheelers.com, retrieved 29 June 2013

- Britain’s 3-Wheel Solution to Mobility for the Disabled, Tudor Van Hampton,3 December 2009

- National Motor Museum (UK): List of Vehicles in the Collection

- http://classiccars.brightwells.com/viewdetails.php?id=5456, retrieved 12 July 2018

- Wagner, Carl (Second Quarter 1973). ""Ist das nicht ein Kabinenroller?" "Ja! das ist ein Kabinenroller!" Carl Wagner takes off on Messerschmitt". Automobile Quarterly. New York, NY: Automobile Quarterly Inc. 11 (2): 162–171. LCCN 62004005

- Duo 4-5 Schwalbennest Simson und mehr - accessed 06 Feb 2011.

- "TECHNICKÁ DATA - OSKAR 54". Archived from the original on 2013-01-05. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- "VELOREX TEAM ZLATÁ RŮŽE BOSKOVICE". Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2017-10-03.