Liberal Democratic Party (Japan)

The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō), frequently abbreviated to LDP or Jimintō (自民党), is a conservative[35] political party in Japan.

Liberal Democratic Party 自由民主党 or 自民党 Jiyū-Minshutō or Jimintō | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Shinzō Abe |

| Deputy Leader | Masahiko Kōmura |

| Secretary-General | Toshihiro Nikai |

| Councilors Leader | Masakazu Sekiguchi |

| Founded | 15 November 1955 |

| Merger of | Japan Democratic Party Liberal Party |

| Headquarters | 11-23, Nagatachō 1-chome, Chiyoda, Tokyo 100-8910, Japan |

| Newspaper | Jiyū Minshu[1] |

| Membership (2019) | (As of 31 December 2019)[2] |

| Ideology | Factions: • Ultranationalism[13][18][19] • Social conservatism[20][21][22] • Liberalism[23][24] |

| Political position | Right-wing[25][a] |

| Colors | Green and Red[26] |

| Anthem | "We" |

| Councillors | 113 / 245 |

| Representatives | 285 / 465 |

| Prefectural assembly members[28] | 1,301 / 2,668 |

| City, special ward, town and village assembly members[28] | 2,180 / 29,762 |

| Election symbol | |

_Emblem.jpg) | |

| Website | |

| jimin.jp | |

^ a: The Liberal Democratic Party is a big-tent conservative party.[29][30] The LDP is also described as centre-right,[31] but the LDP has both far-right[32], ultra-conservative[33] factions, with many members belonging to Nippon Kaigi, and more centrist factions.[34] | |

The LDP has almost continuously been in power since its foundation in 1955—a period called the 1955 System—with the exception of a period between 1993 and 1994, and again from 2009 to 2012. In the 2012 election it regained control of the government. It holds 285 seats in the lower house and 113 seats in the upper house, and in coalition with the Komeito, the governing coalition has a supermajority in both houses. Prime Minister Shinzō Abe and many present and former LDP ministers are also known members of Nippon Kaigi, an ultranationalist[18] and monarchist organization.[36]

The LDP is not to be confused with the now-defunct Liberal Party (自由党, Jiyūtō), which merged with the Democratic Party of Japan (民主党, Minshutō) to become the Democratic Party (民進党, Minshintō), the main opposition party until 2017.[37] The LDP is also not to be confused with the Liberal Party (自由党, Jiyū-tō), a former minor social liberal party founded in 2016.

History

Beginnings

The LDP was formed in 1955 as a merger between two of Japan's political parties, the Liberal Party (自由党, Jiyutō, 1945–1955, led by Shigeru Yoshida) and the Japan Democratic Party (日本民主党, Nihon Minshutō, 1954–1955, led by Ichirō Hatoyama), both right-wing conservative parties, as a united front against the then popular Japan Socialist Party (日本社会党, Nipponshakaitō), now Social Democratic Party (社会民主党, Shakaiminshutō). The party won the following elections, and Japan's first conservative government with a majority was formed by 1955. It would hold majority government until 1993.

The LDP began with reforming Japan's international relations, ranging from entry into the United Nations, to establishing diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union. Its leaders in the 1950s also made the LDP the main government party, and in all the elections of the 1950s, the LDP won the majority vote, with the only other opposition coming from left-wing politics, made up of the Japan Socialist Party and the Japanese Communist Party.

From the 1950s through the 1970s, the United States Central Intelligence Agency spent millions of dollars attempting to influence elections in Japan to favor the LDP against more leftist parties such as the Socialists and the Communists,[38][39] although this was not revealed until the mid-1990s when it was exposed by The New York Times.[40]

1960s to 1990s

For the majority of the 1960s, the LDP (and Japan) were led by Eisaku Satō, beginning with the hosting of the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, and ending in 1972 with Japanese neutrality in the Vietnam War and with the beginning of the Japanese asset price bubble. By the end of the 1970s, the LDP went into its decline, where even though it held the reins of government many scandals plagued the party, while the opposition (now joined with the Komeito (Former)) gained momentum.

In 1976, in the wake of the Lockheed bribery scandals, a handful of younger LDP Diet members broke away and established their own party, the New Liberal Club (Shin Jiyu Kurabu). A decade later, however, it was reabsorbed by the LDP.

By the late 1970s, the Japan Socialist Party, the Japanese Communist Party, and the Komeito along with the international community used major pressure to have Japan switch diplomatic ties from the Republic of China to the People's Republic of China.

By the early 1990s, the LDP's nearly four decades in power allowed it to establish a highly stable process of policy formation. This process would not have been possible if other parties had secured parliamentary majorities. LDP strength was based on an enduring, although not unchallenged, coalition of big business, small business, agriculture, professional groups, and other interests. Elite bureaucrats collaborated closely with the party and interest groups in drafting and implementing policy. In a sense, the party's success was a result not of its internal strength but of its weakness. It lacked a strong, nationwide organization or consistent ideology with which to attract voters. Its leaders were rarely decisive, charismatic, or popular. But it functioned efficiently as a locus for matching interest group money and votes with bureaucratic power and expertise. This arrangement resulted in corruption, but the party could claim credit for helping to create economic growth and a stable, middle-class Japan.

Out of power

But by 1993, the end of the miracle economy and other reasons (e.g. Recruit scandal) led to the LDP losing its majority in that year's general election.

Seven opposition parties—including several formed by LDP dissidents—formed a government headed by LDP dissident Morihiro Hosokawa of the Japan New Party. However, the LDP was still far and away the largest party in the House of Representatives, with well over 200 seats; no other party crossed the 80-seat mark.

In 1994, the Socialist Party and New Party Sakigake left the ruling coalition, joining the LDP in the opposition. The remaining members of the coalition tried to stay in power as a makeshift minority government, but this failed when the LDP and the Socialists, bitter rivals for 40 years, formed a majority coalition. The new government was dominated by the LDP, but it allowed a Socialist to occupy the Prime Minister's chair until 1996, when the LDP's Ryutaro Hashimoto took over.

1996–2009

In the 1996 election, the LDP made some gains, but was still 12 seats short of a majority. However, no other party could possibly form a government, and Hashimoto formed a solidly LDP minority government. Through a series of floor-crossings, the LDP regained its majority within a year.

The party was practically unopposed until 1998, when the opposition Democratic Party of Japan was formed. This marked the beginning of the opposing parties' gains in momentum, especially in the 2003 and 2004 Parliamentary Elections, that wouldn't slow for another 12 years.

In the dramatically paced 2003 House of Representatives elections, the LDP won 237 seats, while the DPJ won 177 seats. In the 2004 House of Councillors elections, in the seats up for grabs, the LDP won 49 seats and the DPJ 50, though in all seats (including those uncontested) the LDP still had a total of 114. Because of this electoral loss, former Secretary General Shinzō Abe turned in his resignation, but Party President Koizumi merely demoted him in rank, and he was replaced by Tsutomu Takebe.

On 10 November 2003, the New Conservative Party (Hoshu Shintō) was absorbed into the LDP, a move which was largely because of the New Conservative Party's poor showing in the 2003 general election. The LDP formed a coalition with the conservative Buddhist New Komeito.

After a victory in the 2005 Japan general election, the LDP held an absolute majority in the Japanese House of Representatives and formed a coalition government with the New Komeito Party. Abe succeeded then-Prime Minister Junichirō Koizumi as the president of the party on 20 September 2006. The party suffered a major defeat in the election of 2007, however, and lost its majority in the upper house for the first time in its history.

The LDP remained the largest party in both houses of the Diet, until 29 July 2007, when the LDP lost its majority in the upper house.[41]

In a party leadership election held on 23 September 2007, the LDP elected Yasuo Fukuda as its president. Fukuda defeated Tarō Asō for the post, receiving 330 votes against 197 votes for Aso.[42][43] However Fukuda resigned suddenly in September 2008, and Asō became Prime Minister after winning the presidency of the LDP in a 5-way election.

In the 2009 general election, the LDP was roundly defeated, winning only 118 seats—easily the worst defeat of a sitting government in modern Japanese history, and also the first real transfer of political power in the post-war era. Accepting responsibility for this severe defeat, Aso announced his resignation as LDP president on election night. Sadakazu Tanigaki was elected leader of the party on 28 September 2009,[44] after a three-way race, becoming only the second LDP leader who was not simultaneously prime minister.

Recent political history

The party's support continued to decline, with prime ministers changing rapidly, and in the 2009 House of Representatives elections the LDP lost its majority, winning only 118 seats, marking the only time they would be out of the majority other than a brief period in 1993.[45][46] Since that time, numerous party members have left to join other parties or form new ones, including Your Party (みんなの党, Minna no Tō), the Sunrise Party of Japan (たちあがれ日本, Tachiagare Nippon),[47] and the New Renaissance Party (新党改革, Shintō Kaikaku). The party had some success in the 2010 House of Councilors election, netting 13 additional seats and denying the DPJ a majority.[48][49] The LDP returned to power with its ally New Komeito after winning a clear majority in the lower house general election on 16 December 2012 after just over three years in opposition. Shinzō Abe became Prime Minister for the second time.[50]

In July 2015, the party pushed for expanded military powers to fight in foreign conflict through Shinzō Abe and the support of Komeito party.[51]

Ideology

The LDP has not espoused a well-defined, unified ideology or political philosophy, due to its long-term government, and has been described as a "catch-all" party.[30] Its members hold a variety of positions that could be broadly defined as being to the right of the opposition parties. The LDP is usually considered politically inclined based on conservatism and Japanese nationalism. The LDP traditionally identified itself with a number of general goals: rapid, export-based economic growth; close cooperation with the United States in foreign and defense policies; and several newer issues, such as administrative reform. Administrative reform encompassed several themes: simplification and streamlining of government bureaucracy; privatization of state-owned enterprises; and adoption of measures, including tax reform, in preparation for the expected strain on the economy posed by an aging society. Other priorities in the early 1990s included the promotion of a more active and positive role for Japan in the rapidly developing Asia-Pacific region, the internationalization of Japan's economy by the liberalization and promotion of domestic demand (expected to lead to the creation of a high-technology information society) and the promotion of scientific research. A business-inspired commitment to free enterprise was tempered by the insistence of important small business and agricultural constituencies on some form of protectionism and subsidies.[52] In addition, the LDP opposes the legalization of same-sex marriage.[20]

Historical

LDP is conservative party. However, in the case of the LDP administration under the 1955 System in Japan, their degree of economic control was stronger than that of the western conservative government; it was also positioned closer to social democracy.[53] Since the 1970s, the oil crisis has slowed economic growth and increased the resistance of urban citizens to policies that favor farmers.[54] To maintain its dominant position, the LDP sought to expand party supporters by incorporating social security policies and pollution measures advocated by opposition parties.[54]

Structure

| Part of a series on |

| Populism |

|---|

|

National variants |

|

Related topics |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

|

Concepts

|

|

Organizations

|

|

Religious conservatism

|

|

National variants |

|

At the apex of the LDP's formal organization is the president (総裁, sōsai), who can serve three[55] three-year terms (The presidential term was increased from two years to three years in 2002, and from two to three terms in 2017). When the party has a parliamentary majority, the party president is the prime minister. The choice of party president is formally that of a party convention composed of Diet members and local LDP figures, but in most cases, they merely approved the joint decision of the most powerful party leaders. To make the system more democratic, Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda introduced a "primary" system in 1978, which opened the balloting to some 1.5 million LDP members. The process was so costly and acrimonious, however, that it was subsequently abandoned in favor of the old "smoke-filled room" method — so-called in allusion to the notion of closed discussions held in small rooms filled with tobacco smoke.

After the party president, the most important LDP officials are the Secretary-General (kanjicho), and the chairmen of the LDP Executive Council (somukaicho) and of the Policy Affairs Research Council or "PARC" (政務調査会, seimu chōsakai).

The LDP is the most "traditionally Japanese" of the political parties because it relies on a complex network of patron-client (oyabun-kobun) relationships on both national and local levels. Nationally, a system of factions in both the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors ties individual Diet members to powerful party leaders. Locally, Diet members have to maintain koenkai (local support groups) to keep in touch with public opinion and gain votes and financial backing. The importance and pervasiveness of personal ties between Diet members and faction leaders and between citizens and Diet members gives the party a pragmatic "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" character. Its success depends less on generalized mass appeal than on the so-called sanban (three "ban"): jiban (a strong, well-organized constituency), kaban (a briefcase full of money), and kanban (prestigious appointment, particularly on the cabinet level).

Leadership

| Position | Name | Faction |

|---|---|---|

| President | Shinzō Abe | Hosoda (Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyū-kai) |

| Deputy leader | Masahiko Kōmura | Asō (Shikō-kai) |

| Secretary-General | Toshihiro Nikai | Nikai (Shisui-kai) |

| Vice Secretary-General | Kōichi Hagiuda | Hosoda |

| Deputy Secretary-General | Motoo Hayashi | Asō |

| Katsutoshi Kaneda | Takeshita (Heisei Kenkyū-kai) | |

| Naoki Okada | Hosoda | |

| Policy Affairs Research Council chief | Fumio Kishida | Kishida (Kōchi-kai) |

| Financial Affairs Committee chief | Yūji Yamamoto | Ishiba (Suigetsu-kai) |

| Election Campaign Committee chief | Ryū Shionoya | Hosoda |

| Party Organization general manager | Taimei Yamaguchi | Takeshita |

| Public Relations general manager | Takuya Hirai | Kishida |

| Diet Affairs Committee chief | Hiroshi Moriyama | Ishihara (Kinmirai Seiji Kenkyū-kai) |

| Chief Party Whip | Akiko Santō | Asō |

| Representatives General Council chief | Hajime Funada | Takeshita |

| General Affairs Council chief | Wataru Takeshita | Takeshita |

| Joint House General Council chief | Hidehisa Otsuji | Takeshita |

| Councillors General Council chief | Seiko Hashimoto | Hosoda |

| Councillors General Council Secretary-General | Hiromi Yoshida | Takeshita |

| Councillors Policy Affairs Council chief | Keizō Takemi | Asō |

| Councillors Diet Affairs Committee chief | Masakazu Sekiguchi | Takeshita |

| Central Political Graduate School director | Takeshi Iwaya | Asō |

Factions

Membership

The LDP had over five million party members in 1990. By December 2017 membership had dropped to approximately one million members.[2]

Performance in national elections until 1993

Election statistics show that, while the LDP had been able to secure a majority in the twelve House of Representatives elections from May 1958 to February 1990, with only three exceptions (December 1976, October 1979, and December 1983), its share of the popular vote had declined from a high of 57.8 percent in May 1958 to a low of 41.8 percent in December 1976, when voters expressed their disgust with the party's involvement in the Lockheed scandal. The LDP vote rose again between 1979 and 1990. Although the LDP won an unprecedented 300 seats in the July 1986 balloting, its share of the popular vote remained just under 50 percent. The figure was 46.2 percent in February 1990. Following the three occasions when the LDP found itself a handful of seats shy of a majority, it was obliged to form alliances with conservative independents and the breakaway New Liberal Club. In a cabinet appointment after the October 1983 balloting, a non-LDP minister, a member of the New Liberal Club, was appointed for the first time. On 18 July 1993, lower house elections, the LDP fell so far short of a majority that it was unable to form a government.

In the upper house, the July 1989 election represented the first time that the LDP was forced into a minority position. In previous elections, it had either secured a majority on its own or recruited non-LDP conservatives to make up the difference of a few seats.

The political crisis of 1988–89 was testimony to both the party's strength and its weakness. In the wake of a succession of issues—the pushing of a highly unpopular consumer tax through the Diet in late 1988, the Recruit insider trading scandal, which tainted virtually all top LDP leaders and forced the resignation of Prime Minister Takeshita Noboru in April (a successor did not appear until June), the resignation in July of his successor, Uno Sōsuke, because of a sex scandal, and the poor showing in the upper house election—the media provided the Japanese with a detailed and embarrassing dissection of the political system. By March 1989, popular support for the Takeshita cabinet as expressed in public opinion polls had fallen to 9 percent. Uno's scandal, covered in magazine interviews of a "kiss and tell" geisha, aroused the fury of female voters.

Uno's successor, the eloquent if obscure Kaifu Toshiki, was successful in repairing the party's battered image. By January 1990, talk of the waning of conservative power and a possible socialist government had given way to the realization that, like the Lockheed affair of the mid-1970s, the Recruit scandal did not signal a significant change in who ruled Japan. The February 1990 general election gave the LDP, including affiliated independents, a comfortable, if not spectacular, majority: 275 of 512 total representatives.

In October 1991, Prime Minister Kaifu Toshiki failed to attain passage of a political reform bill and was rejected by the LDP, despite his popularity with the electorate. He was replaced as prime minister by Miyazawa Kiichi, a long-time LDP stalwart. Defections from the LDP began in the spring of 1992, when Hosokawa Morihiro left the LDP to form the Japan New Party. Later, in the summer of 1993, when the Miyazawa government also failed to pass political reform legislation, thirty-nine LDP members joined the opposition in a no-confidence vote. In the ensuing lower house election, more than fifty LDP members formed the Shinseitō and the Sakigake parties, denying the LDP the majority needed to form a government.

Presidents of the Liberal Democratic Party

With the exception of Yohei Kono and Sadakazu Tanigaki, every President of the LDP (自由民主党総裁, Jiyū-Minshutō Sōsai)[56] has also served as Prime Minister of Japan.

| No. | Name | Term of office | Election results | Image | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took Office | Left Office | ||||

| Preceding parties: Democratic Party (1954) & Liberal Party (1950) | |||||

| Interim Leadership Committee | |||||

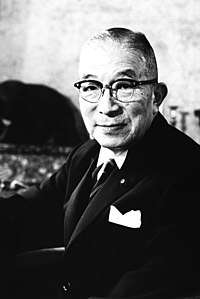

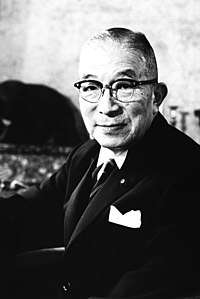

| – | Ichirō Hatoyama | 15 November 1955 | 5 April 1956 | Interim Leadership Committee |  |

| Bukichi Miki |  | ||||

| Banboku Oono | |||||

| Taketora Ogata | 28 January 1956 |  | |||

| Tsuruhei Matsuno | 10 February 1956 | 5 April 1956 | |||

| Leader | |||||

| 1 | Ichirō Hatoyama | 5 April 1956 | 14 December 1956 |

Ichirō Hatoyama – 394 Nobusuke Kishi – 4 Others – 15 |

|

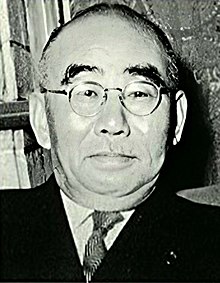

| 2 | Tanzan Ishibashi | 14 December 1956 | 21 March 1957 | 1st Round

Nobusuke Kishi – 223 Tanzan Ishibashi – 151 Mitsujiro Ishii – 137 2nd Round

Tanzan Ishibashi – 258 Nobusuke Kishi – 251 |

|

| 3 | Nobusuke Kishi | 21 March 1957 | 14 July 1960 | 1957

Nobusuke Kishi – 471 Kenzō Matsumura – 2 Tokutaro Kitamura – 1 Mitsujirō Ishii – 1 1959

Nobusuke Kishi – 320 Kenzō Matsumura – 166 Others – 5 |

|

| 4 | Hayato Ikeda | 14 July 1960 | 1 December 1964 | 1960 1st Round

Hayato Ikeda – 246 Mitsujirō Ishii – 194 Aiichirō Fujiyama – 49 Others – 7 1960 2nd Round

Hayato Ikeda – 302 Mitsujirō Ishii – 194 1962

Hayato Ikeda – 391 Eisaku Satō – 17 Others – 20 July 1964

Hayato Ikeda – 242 Eisaku Satō – 160 Aiichirō Fujiyama – 72 Hirokichi Nadao – 1 |

|

| 5 | Eisaku Satō | 1 December 1964 | 5 July 1972 | November 1964

Eisaku Satō – Aiichirō Fujiyama – Ichirō Kōno – 1966

Eisaku Satō – 289 Aiichirō Fujiyama – 89 Shigesaburō Maeo – 47 Hirokichi Nadao – 11 Uichi Noda – 9 Others – 5 1968

Eisaku Satō – 249 Takeo Miki – 107 Shigesaburō Maeo – 95 Others – 25 1970

Eisaku Satō – 353 Takeo Miki – 111 Others – 3 |

|

| 6 | Kakuei Tanaka | 5 July 1972 | 4 December 1974 |

Tanaka Kakuei – 282 Takeo Fukuda – 180 |

|

| 7 | Takeo Miki | 4 December 1974 | 23 December 1976 | 1974

Takeo Miki – Takeo Fukuda – Masayoshi Ōhira – Yasuhiro Nakasone – |

|

| 8 | Takeo Fukuda | 23 December 1976 | 1 December 1978 | 1976

Takeo Fukuda – Masayoshi Ōhira – |

|

| 9 | Masayoshi Ōhira (Died in office) |

1 December 1978 | 12 June 1980 | 1st Round

Masayoshi Ōhira – 748 Fukuda Takeo – 638 Yasuhiro Nakasone – 93 Toshio Kōmoto – 46 2nd Round

Unopposed |

|

| — | Eiichi Nishimura | 12 June 1980 | 15 July 1980 | Acting |  |

| 10 | Zenkō Suzuki | 15 July 1980 | 25 November 1982 | 1st Round

Zenko Suzuki – Kiichi Miyazawa – Yasuhiro Nakasone – Toshio Kōmoto – 2nd Round

Unopposed |

|

| 11 | Yasuhiro Nakasone | 25 November 1982 | 31 October 1987 | 1982 1st Round

Yasuhiro Nakasone – 57.6% (559,673) Toshio Kōmoto – 27.2% (265,078) Shintarō Abe – 8.2% (80,443) Ichirō Nakagawa – 6.8% (66,041) 1982 2nd Round

Unopposed 1984

Unopposed Walkover 1986

1-year Extension |

|

| 12 | Noboru Takeshita | 31 October 1987 | 2 June 1989 | 1987

Noboru Takeshita – Shintarō Abe – Kiichi Miyazawa – |

|

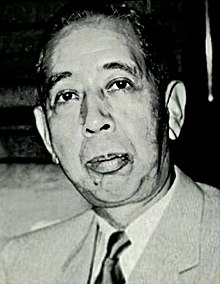

| 13 | Sōsuke Uno | 2 June 1989 | 8 August 1989 | 1989

Sōsuke Uno – Masayoshi Itō – |

|

| 14 | Toshiki Kaifu | 8 August 1989 | 30 October 1991 | 1st Round

Toshiki Kaifu – 279 Yoshirō Hayashi – 120 Shintarō Ishihara – 48 2nd Round

Unopposed |

|

| 15 | Kiichi Miyazawa | 31 October 1991 | 29 July 1993 |

Kiichi Miyazawa – 285 Michio Wantanabe – 120 Hiroshi Mitsuzuka – 87 |

|

| 16 | Yōhei Kōno | 29 July 1993 | 1 October 1995 | 1st Round

Yōhei Kōno – 208 Michio Wantanabe – 159 2nd Round

Unopposed |

|

| 17 | Ryutaro Hashimoto | 1 October 1995 | 24 July 1998 | 1995

Ryutaro Hashimoto – 304 Junichiro Koizumi – 87 1997

Unopposed Walkover |

|

| 18 | Keizō Obuchi | 24 July 1998 | 5 April 2000 | 1998

Keizō Obuchi – 225 Seiroku Kajiyama – 102 Junichiro Koizumi – 84 1999

Keizō Obuchi – 350 Koichi Kato – 113 Taku Yamasaki – 51 |

|

| 19 | Yoshirō Mori | 5 April 2000 | 24 April 2001 | 2000

Yoshirō Mori – Mikio Aoki – Masakuni Murakami – Hiromu Nonaka – Shizuka Kamei – |

|

| 20 | Junichiro Koizumi | 24 April 2001 | 20 September 2006 | 2001 1st Round

Junichiro Koizumi – 298 Ryutaro Hashimoto – 155 Tarō Asō – 31 2001 2nd Round

Unopposed 2003 |

|

| 21 | Shinzō Abe | 20 September 2006 | 26 September 2007 |

Shinzō Abe – 464 Tarō Asō – 136 Sadakazu Tanigaki – 102 |

|

| 22 | Yasuo Fukuda | 26 September 2007 | 22 September 2008 |

Yasuo Fukuda – 330 Tarō Asō – 197 |

|

| 23 | Tarō Asō | 22 September 2008 | 16 September 2009 |  | |

| 24 | Sadakazu Tanigaki | 28 September 2009 | 26 September 2012 |  | |

| (21) | Shinzō Abe | 26 September 2012 | Incumbent | 2012 1st Round

Shinzō Abe – 464 Shigeru Ishiba – 199 Nobuteru Ishihara – 96 Nobutaka Machimura 34 Yoshimasa Hayashi – 27 2012 2nd Round

Shinzō Abe – 108 Shigeru Ishiba – 89 2015

Unopposed Walkover

Shinzō Abe – 553 Shigeru Ishiba – 254 |

|

Election results

General election results

| Election | Leader | Candidates | Seats | Constituency votes | PR Block votes | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |||||

| 1958 | Nobusuke Kishi | 413 | 289 / 467 |

23,840,170 | 59.0% | Government | ||

| 1960 | Hayato Ikeda | 399 | 300 / 467 |

22,950,404 | 58.1% | Government | ||

| 1963 | Hayato Ikeda | 359 | 283 / 467 |

22,972,892 | 56.0% | Government | ||

| 1967 | Eisaku Satō | 342 | 277 / 486 |

22,447,838 | 48.9% | Government | ||

| 1969 | Eisaku Satō | 328 | 288 / 486 |

22,381,570 | 47.6% | Government | ||

| 1972 | Tanaka Kakuei | 339 | 271 / 491 |

24,563,199 | 46.9% | Government | ||

| 1976 | Takeo Miki | 320 | 249 / 511 |

23,653,626 | 41.8% | Government | ||

| 1979 | Masayoshi Ōhira | 322 | 248 / 511 |

24,084,130 | 44.59% | Government | ||

| 1980 | Masayoshi Ōhira | 310 | 284 / 511 |

28,262,442 | 47.88% | Government | ||

| 1983 | Yasuhiro Nakasone | 339 | 250 / 511 |

25,982,785 | 45.76% | LDP-NLC coalition | ||

| 1986 | Yasuhiro Nakasone | 322 | 300 / 512 |

29,875,501 | 49.42% | Government | ||

| 1990 | Toshiki Kaifu | 338 | 275 / 512 |

30,315,417 | 46.14% | Government | ||

| 1993 | Kiichi Miyazawa | 285 | 223 / 511 |

22,999,646 | 36.62% | Opposition (until 1994) | ||

| LDP-JSP-NPS coalition (since 1994) | ||||||||

| 1996 | Ryutaro Hashimoto | 355 | 239 / 500 |

21,836,096 | 38.63% | 18,205,955 | 32.76% | LDP-SDP-NPS coalition |

| 2000 | Yoshirō Mori | 337 | 233 / 480 |

24,945,806 | 40.97% | 16,943,425 | 28.31% | LDP-NKP-NCP coalition |

| 2003 | Junichiro Koizumi | 336 | 237 / 480 |

26,089,326 | 43.85% | 20,660,185 | 34.96% | LDP-NKP coalition |

| 2005 | Junichiro Koizumi | 346 | 296 / 480 |

32,518,389 | 47.80% | 25,887,798 | 38.20% | LDP-NKP coalition |

| 2009 | Tarō Asō | 326 | 119 / 480 |

27,301,982 | 38.68% | 18,810,217 | 26.73% | Opposition |

| 2012 | Shinzō Abe | 337 | 294 / 480 |

25,643,309 | 43.01% | 16,624,457 | 27.79% | LDP-NKP coalition |

| 2014 | Shinzō Abe | 352 | 291 / 475 |

25,461,427 | 48.10% | 17,658,916 | 33.11% | LDP-KM coalition |

| 2017 | Shinzō Abe | 332 | 284 / 465 |

26,719,032 | 48.21% | 18,555,717 | 33.28% | LDP-KM coalition |

Councillors election results

| Election | Leader | Seats | Nationwide[lower-alpha 1] | Prefecture | Status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total[lower-alpha 2] | Contested | Number | % | Number | % | |||

| 1956 | Ichirō Hatoyama | 122 / 250 |

61 / 125 |

11,356,874 | 39.7% | 14,353,960 | 48.4% | Governing minority |

| 1959 | Nobusuke Kishi | 132 / 250 |

71 / 125 |

12,120,598 | 41.2% | 15,667,022 | 52.0% | Governing majority |

| 1962 | Hayato Ikeda | 142 / 250 |

69 / 125 |

16,581,637 | 46.4% | 17,112,986 | 47.1% | Governing majority |

| 1965 | Eisaku Satō | 140 / 251 |

71 / 125 |

17,583,490 | 47.2% | 16,651,284 | 44.2% | Governing majority |

| 1968 | Eisaku Satō | 137 / 250 |

69 / 125 |

20,120,089 | 46.7% | 19,405,546 | 44.9% | Governing majority |

| 1971 | Eisaku Satō | 131 / 249 |

62 / 125 |

17,759,395 | 44.5% | 17,727,263 | 44.0% | Governing majority |

| 1974 | Kakuei Tanaka | 126 / 250 |

62 / 125 |

23,332,773 | 44.3% | 21,132,372 | 39.5% | Governing majority |

| 1977 | Takeo Fukuda | 125 / 249 |

63 / 125 |

18,160,061 | 35.8% | 20,440,157 | 39.5% | Governing minority |

| 1980 | Masayoshi Ōhira | 135 / 250 |

69 / 125 |

23,778,190 | 43.3% | 24,533,083 | 42.5% | Governing majority |

| 1983 | Yasuhiro Nakasone | 137 / 252 |

68 / 126 |

16,441,437 | 35.3% | 19,975,034 | 43.2% | Governing majority |

| 1986 | Yasuhiro Nakasone | 143 / 252 |

72 / 126 |

22,132,573 | 38.58% | 26,111,258 | 45.07% | Governing majority |

| 1989 | Sōsuke Uno | 109 / 252 |

36 / 126 |

15,343,455 | 27.32% | 17,466,406 | 30.70% | Governing minority |

| 1992 | Kiichi Miyazawa | 106 / 252 |

68 / 126 |

14,961,199 | 33.29% | 20,528,293 | 45.23% | Governing minority (until 1993) |

| Minority (1993–1994) | ||||||||

| LDP-JSP-NPS governing majority (since 1994) | ||||||||

| 1995 | Yōhei Kōno | 111 / 252 |

46 / 126 |

10,557,547 | 25.40% | 11,096,972 | 27.29% | LDP-JSP-NPS governing majority |

| 1998 | Ryutaro Hashimoto | 102 / 252 |

44 / 126 |

14,128,719 | 25.17% | 17,033,851 | 30.45% | LDP–(Lib.–Komeitō) governing majority (until 2000) |

| LDP–Komeitō–NCP governing majority (since 2000) | ||||||||

| 2001 | Junichiro Koizumi | 111 / 247 |

64 / 121 |

21,114,727 | 38.57% | 22,299,825 | 41.04% | LDP–Komeitō–NCP governing majority (until 2003) |

| LDP–Komeitō governing majority (since 2003) | ||||||||

| 2004 | Junichiro Koizumi | 115 / 242 |

49 / 121 |

16,797,686 | 30.03% | 19,687,954 | 35.08% | LDP–Komeitō governing majority |

| 2007 | Shinzō Abe | 83 / 242 |

37 / 121 |

16,544,696 | 28.1% | 18,606,193 | 31.35% | LDP–Komeitō governing minority (until 2009) |

| Minority (since 2009) | ||||||||

| 2010 | Sadakazu Tanigaki | 84 / 242 |

51 / 121 |

14,071,671 | 24.07% | 19,496,083 | 33.38% | Minority (until 2012) |

| LDP–Komeitō governing minority (since 2012) | ||||||||

| 2013 | Shinzō Abe | 115 / 242 |

65 / 121 |

18,460,404 | 34.7% | 22,681,192 | 42.7% | LDP–Komeitō governing majority |

| 2016 | Shinzō Abe | 121 / 242 |

56 / 121 |

20,114,833 | 35.9% | 22,590,793 | 39.9% | LDP–Komeitō governing majority |

| 2019 | Shinzō Abe | 113 / 245 |

57 / 124 |

20,330,963 | 39.77% | 17,711,862 | 35.37% | LDP–Komeitō governing majority |

See also

Notes

- From 1947 to 1980, 50 members were elected through a nationwide constituency, known as the "national block" (Plurality-at-large voting). It was replaced in 1983 by a proportional representation block with closed lists. In 2001, the PR block was reduced to 48 members with most open lists.

- The Upper house is split in two classes, one elected every three years.

References

- Japan Country Studies – Library of Congress

- 機関紙誌のご案内. Liberal Democratic Party.

- 自民党員7年ぶり減少 108万人、19年末時点. The Nihon Keizai Shinbun. 2 March 2020.

- "Japan's leaders, less apologetic, stay tough in S. Korea feud". Asahi Shimbun. 8 August 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

Two years later, then-Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama, a socialist who led a coalition with the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, made a "heartfelt apology" for suffering caused by Japan's "colonial rule and aggression."

- "Abe faces major election hurdle in bid to amend Constitution". Mainichi Daily News. Mainichi Shimbun. 8 January 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

... he should venture to dissolve the House of Representatives for a snap general election to coincide with the upper house poll," said a conservative LDP legislator.

- "Japan readies for July 21 upper house election as PM recalls past defeat". Reuters. 26 June 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

He was referring to events that unfolded after his conservative LDP suffered a huge defeat in a 2007 upper house poll. Two months later, Abe quit as premier after just one year.

- McCurry, Justin (6 March 2020). "Japan prefecture to stop hiring female 'tea squad' for meetings". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

But Nobuaki Kojima, who heads the conservative Liberal Democratic party group in the assembly, said the change was also a recognition of changing attitudes towards women in the workplace.

- "Japan ministers Yuko Obuchi and Midori Matsushima quit". BBC News. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

Mr Abe said he took responsibility for having appointed both women, and that they would be replaced within a day. Both are members of his governing conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

- "Poll finds nearly two-thirds oppose passage of casino bill; Cabinet's approval rating falls to 43.4%". The Japan Times. Kyodo. 23 July 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

The telephone poll conducted by Kyodo News over the weekend found that 64.8 percent of respondents opposed the legislation and 27.6 percent supported it. The Diet, dominated by the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, passed the bill on Friday despite stiff resistance from opposition parties.

- Newlands, Peter (16 December 2012). "Conservatives win by a landslide in Japanese general election". The Times. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

Exit polls indicated that the conservative Liberal Democratic party has been returned to office after winning almost 300 seats in the lower house, which has 480 members. The new prime minister will be Shinzo Abe, a hawkish former prime minister, who is expected to revise the country’s pacifist constitution.

[The] conservative Liberal Democratic party in Japan won back power in an election landslide today, returning Shinzo Abe, a former prime minister. - "The Resurgence of Japanese Nationalism (the Globalist)". 22 July 2015. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- "As Hiroshima's legacy fades, Japan's postwar pacifism is fraying". The Conversation UK. 6 August 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

Even though much of the Japanese public does not agree with the LDP’s nationalist platform, the party won big electoral victories by promising to replace the DPJ's weakness with strong leadership – particularly on the economy, but also in foreign affairs.

- "Why Steve Bannon Admires Japan". The Diplomat. 22 June 2018.

In Japan, populist and extreme right-wing nationalism has found a home within the political establishment.

- "Shinzo Abe and the rise of Japanese nationalism". New Statesman. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

As a new emperor takes the throne, prime minister Abe is consolidating his ultranationalist “beautiful Japan” project. But can he overcome a falling population and stagnating economy?

- A Weiss (31 May 2018). Towards a Beautiful Japan: Right-Wing Religious Nationalism in Japan's LDP.

- Lindgren, Petter (2012). "The Era of Koizumi's Right-Wing Populism" (PDF). University of Oslo.

- Ganesan (2015). Bilateral Legacies in East and Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 67.

- Hebert (2011). Wind Bands and Cultural Identity in Japanese Schools. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 44.

- "Beautiful Harmony: Political Project Behind Japan's New Era Name – Analysis". eurasia review. 16 July 2019. Archived from the original on 13 August 2019. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

The shifting dynamics around the new era name (gengō 元号) offers an opportunity to understand how the domestic politics of the LDP’s project of ultranationalism is shaping a new Japan and a new form of nationalism.

- "Abe's cabinet reshuffle". East Asia Forum. 14 September 2019.

Abe also rewarded right-wing politicians who are close to him — so-called ‘ideological friends’ who are being increasingly pushed to the forefront of his administration — such as LDP Executive Acting Secretary-General Koichi Hagiuda who was appointed Education Minister. As a member of the ultranationalist Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), which seeks to promote patriotic education, he can be considered ‘reliable’ as the government’s policy leader on national education.

- Inada, Miho; Dvorak, Phred. "Same-Sex Marriage in Japan: A Long Way Away?" Archived 16 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Wall Street Journal. 20 September 2013. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Shinzo Abe? That's Not His Name, Says Japan's Foreign Minister". The New York Times. 22 May 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "Japan's capricious response to coronavirus could dent its international reputation". The Conversation. 24 April 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "今さら聞けない?! 「保守」「リベラル」ってなんだ?" [Can't you ask about them now ?! What are "conservative" and "liberal"?] (in Japanese). Retrieved 5 June 2020.

ところが、現実の政治はもっと複雑です。自民党にもリベラル派がたくさんいるからです。自民党は考え方の近い人たちが派閥というグループをつくっています。(However, real politics is more complicated. This is because there are many liberals in the LDP. The Liberal Democratic Party is made up of groups of people with similar ideas, called factions.)

- "岸田派の政策、リベラル色前面に 安倍政権との違い強調" [Kishida faction's policy emphasizes the difference from the Abe administration on the liberal front]. Asahi Shimbun.

「トップダウンからボトムアップへ」「多様性を尊重する社会へ」など、リベラル色を前面に掲げ、安倍政権との違いを強調した。(He emphasized the differences from the Abe administration by putting liberal colors in the foreground, such as "from top-down to bottom-up" and "to a society that respects diversity".)

-

- "Unwelcome Change – A Cabinet Reshuffle Poses Risks For Japan's Ties with Neighbors". The Economist. 30 August 2014.

- "In a Major Shift, South Korea Defies Its Alliance With Japan". The Nation. 27 August 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- William E. Carroll (June 2018). "Far Right Parties and Movements in Europe, Japan, and the Tea Party in the U.S." (PDF). American Research Institute for Policy Development.

- Kate Wexler (2020). "The Power of Politics: How Right-Wing Political Parties Shifted Japanese Strategic Culture". International Affairs Program (University of Colorado, Boulder).

- Arthur Alexander (June 2018). "Expert Voices on Japan: Security, Economic, Social, and Foreign Policy Recommendations" (PDF). Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation.

- Tessa Morris-Suzuki, ed. (2013). Showa: An Inside History of Hirohito's Japan. A&C Black. p. 303.

- Yoshiko Nozaki, ed. (2008). War Memory, Nationalism and Education in Postwar Japan: The Japanese History Textbook Controversy and Ienaga Saburo's Court Challenges (Routledge Contemporary Japan). Routledge.

- Michael Lewis, ed. (2016). 'History Wars' and Reconciliation in Japan and Korea: The Roles of Historians, Artists and Activists. Springer.

- Linus Hagström, ed. (2005). Japan's China Policy: A Relational Power Analysis. Routledge.

- 日本に定着するか、政党のカラー. The Nikkei (in Japanese). Nikkei, Inc. 21 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- 党歌・シンボル. jimin.jp. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, party membership statistics for chief executives and assembly members in prefectures and municipalities: Prefectural and local assembly members and governors/mayors by political party as of 31 December 2019

- Lucien Ellington, ed. (2009). Japan. ABC-CLIO. p. 81.

- Glenn D. Hook; Julie Gilson; Christopher W. Hughes; Hugo Dobson (2001). Japan's International Relations: Politics, Economics and Security. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-134-32806-2.

-

- Ludger Helms (18 October 2013). Parliamentary Opposition in Old and New Democracies. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-317-97031-6.

- "Overseas Business Risk - Japan". GOV.UK. 31 January 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Roger Blanpain; Michele Tiraboschi (2008). The Global Labour Market:From Globalization to Flexicurity. Kluwer Law International. p. 268. ISBN 978-90-411-2722-8.

- Jeffrey Henderson; William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of Greek Language and Literature Jeffrey Henderson (11 February 2011). East Asian Transformation:On the Political Economy of Dynamism, Governance and Crisis. Taylor & Francis. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-136-84113-2.

- Peter Davies; Derek Lynch (16 August 2005). The Routledge Companion to Fascism and the Far Right. Routledge. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-134-60952-9.

- "Japan is having an election next month. Here's why it matters". Vox. 28 September 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

Abe’s center-right Liberal Democratic Party (LDP),

-

- "Why Steve Bannon Admires Japan". The Diplomat. 22 June 2018.

In Japan, populist and extreme right-wing nationalism has found a home within the political establishment.

- "The Dangerous Impact of the Far-Right in Japan". Washington Square News. 15 April 2019.

Another sign of the rise of the uyoku dantai’s ideas is the growing power of the Nippon Kaigi. The organization is the largest far-right group in Japan and has heavy lobbying clout with the conservative LDP; 18 of the 20 members of Shinzo Abe’s cabinet were once members of the group.

- Wesley Yee (January 2018). "Making Japan Great Again: Japan's Liberal Democratic Party as a Far Right Movement". The University of San Francisco.

- "Japan's ruling party under fire over links to far-right extremists". The Guardian. 13 October 2014.

- "For Abe, it will always be about the Constitution". The Japan Times. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

Of those three victories, the first election in December 2012 was a rout of the leftist Democratic Party of Japan and it thrust the more powerful Lower House of Parliament firmly into the hands of the long-incumbent Liberal Democratic Party under Abe. The second election in December 2014 further normalized Japan’s lurch to the far right, giving the ruling coalition a supermajority of 2/3 of the seats in the Lower House.

- "Shinzo Abe? That's Not His Name, Says Japan's Foreign Minister". The New York Times. 22 May 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

Mr. Abe is strongly supported by the far right wing of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party, which hews to tradition and tends toward insularity.

- Alisa Gaunder, ed. (2011). Routledge Handbook of Japanese Politics. Taylor & Francis. p. 225.

- New Statesman Society. Statesman & Nation Publishing Company. 1995. p. 11.

- Searchlight, Issues 307-318. Searchlight. 2001. p. 31.

- Asia Pacific Business Travel Guide. Priory Publications (Cornell University). 1994. p. 173.

- Trevor Harrison, ed. (2007). 21st century Japan: a new sun rising l Politics in Postwar Japan. Black Rose Books. p. 82.

... of the war and viewed the 1947 Constitution as illegitimate as it was written not by the Japanese people but forced upon the country by the U.S. Occupation Authority. Abe shares these beliefs, in common with many within the LDP's far right.

- Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Atomic Scientists of Chicago. 1983. p. 14.

... 12 Seirankai: an extreme-right faction formed within the LDP in July 1973; after Kim Dae Jung was abducted from ...

- David M. O'Brien, Yasuo goshi, ed. (1996). To Dream of Dreams: Religious Freedom and Constitutional Politics in Postwar Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63.

- J. A. A. Stockwin, ed. (2003). Dictionary of the Modern Politics of Japan. Routledge. p. 88.

- "Why Steve Bannon Admires Japan". The Diplomat. 22 June 2018.

-

- "Japan is having an election next month. Here's why it matters". The Japan Times. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

When Abe appointed five female ministers in September, two of which were forced to step down over scandals, a number of political commentators viewed the move with some cynicism, suggesting that the prime minister didn’t pay much attention to the qualifications of the candidates. Most of the women he chose were ultra-conservatives such as Eriko Yamatani, minister in charge of the North Korea abductee issue.

- "Japan, led by less apologetic generation, stays tough in South Korea feud". Reuters. 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

Electoral system changes and three years in opposition helped ultra-conservative lawmakers and lobby groups strengthen their clout in the LDP.

- "Japan is having an election next month. Here's why it matters". The Japan Times. 22 November 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

-

- "Portrait of Japan's main political parties". 17 December 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

A union of centrist and rightwing parties created with US support after the second world war

- "Freedom house 2016 Japan". Freedom house.

The LDP is a broad party whose members share a commitment to economic growth and free trade, but whose other political beliefs span from the center to the far right.

- "Portrait of Japan's main political parties". 17 December 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- The Liberal Democratic Party is widely described as conservative:

- Roger Blanpain; Michele Tiraboschi; Pablo Arellano Ortiz (2008). The Global Labour Market: From Globalization to Flexicurity. Kluwer Law International. p. 268. ISBN 978-90-411-2722-8.

- Jeff Kingston (2011). Japan in Transformation, 1945-2010. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-317-86192-8.

- Bradley Richardson (2001). "Japan's "1955 System" and Beyond". In Larry Diamond; Richard Gunther (eds.). Political Parties and Democracy. JHU Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8018-6863-4.

- Paul W. Zagorski (2009). Comparative Politics: Continuity and Breakdown in the Contemporary World. Routledge. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-135-96979-0.

- Ray Christensen (2000). Ending the LDP Hegemony: Party Cooperation in Japan. University of Hawaii Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-8248-2295-8.

- "Tea Party Politics in Japan Archived 17 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine" (New York Times – 2014/09/13)

- "The Democratic Party of Japan". Democratic Party of Japan. 2006. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- Weiner, Tim (9 October 1994). "C.I.A. Spent Millions to Support Japanese Right in 50's and 60's". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- "Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Vol. XXIX, Part 2, Japan". United States Department of State. 18 July 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- Johnson, Chalmers (1995). "The 1955 System and the American Connection: A Bibliographic Introduction". JPRI Working Paper No. 11.

- Norimitsu Onishi; Yasuko Kamiizumi; Makiko Inoue (29 July 2007). "Premier's Party Suffers Big Defeat in Japan". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- Martig, Naomi (23 September 2007). "Japan's Ruling Party Chooses New Leader". VOA News. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- "Fukuda wins LDP race / Will follow in footsteps of father as prime minister", The Daily Yomiuri, 23 September 2007.

- Sadakazu Tanigaki Elected LDP President "China Plus". Archived from the original on 10 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- "'Major win' for Japan opposition". BBC News. 30 August 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- 衆院党派別得票数・率(比例代表) (in Japanese). Jiji. 31 August 2009. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014.

- Martin, Alex (11 April 2010). "LDP defectors launch new political party". The Japan Times. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- "House of Councillors The National Diet of Japan". Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- 参議院インターネット審議中継. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- The Japan Times

- NYT, 2015 Archived 14 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- The Liberal Democratic Party – "Japan - THE LIBERAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY". Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Kume, Ikuo; Kawade, Yoshie; Kojo, Yoshiko; Tanaka, Aiji; Mabuchi, Masaru (2011). Political Science: Scope and Theory, revised ed. New Liberal Arts Selection (in Japanese). Yuhikaku Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-4-641-05377-9.

ただし、日本の55年体制下の自民党政権の場合は欧米の保守政権に比べるとかなり経済的統制の度合いが強く、社会民主主義により近い場所に位置した。

- Iio, Jun (2019). Gendai nihon no seiji. Hōsō daigaku kyōzai (in Japanese). Hōsō daigaku kyōiku shinkōkai. p. 104. ISBN 978-4-595-31946-4.

- seokhwai@st (5 March 2017). "New rules give Japan's Shinzo Abe chance to lead until 2021". The Straits Times.

- "The President | Liberal Democratic Party of Japan". www.jimin.jp.

Bibliography

- Helms, Ludger (2013). Parliamentary Opposition in Old and New Democracies. Routledge Press. ISBN 978-1-31797-031-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Henderson, Jeffrey (2011). East Asian Transformation: On the Political Economy of Dynamism, Governance and Crisis. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-13684-113-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Köllner, Patrick. "The Liberal Democratic Party at 50: Sources of Dominance and Changes in the Koizumi Era," Social Science Japan Journal (Oct 2006) 9#2 pp 243–257.

- Krauss, Ellis S., and Robert J. Pekkanen. "The Rise and Fall of Japan's Liberal Democratic Party," Journal of Asian Studies (2010) 69#1 pp 5–15, focuses on the 2009 election.

- Krauss, Ellis S., and Robert J. Pekkanen, eds. The Rise and Fall of Japan's LDP: Political Party Organizations as Historical Institutions (Cornell University Press; 2010) 344 pages; essays by scholars

- Scheiner, Ethan. Democracy without Competition in Japan: Opposition Failure in a One-Party Dominant State (Cambridge University Press, 2006)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Liberal Democratic Party of Japan. |