Pink tide

The pink tide (Spanish: marea rosa, Portuguese: onda rosa, French: mareé rose), or turn to the left (Spanish: giro a la izquierda, Portuguese: guinada à esquerda, French: tourne à gauche), is the revolutionary wave and perception of a turn towards left-wing governments in Latin American democracies straying away from the neoliberal economic model. As a term, both phrases are used in contemporary 21st-century political analysis in the media and elsewhere to refer to the shift representing a move toward more progressive economic policies and coinciding with a parallel trend of democratization of Latin America following decades of inequality.[1][2][3]

The Latin American countries viewed as part of this ideological trend have been referred to as pink tide nations,[4] with the term post-neoliberalism being used to describe the movement as well.[5] Some pink tide governments such as those of Brazil and Venezuela[6] have been varyingly characterized as being anti-American,[7][8] populist[9][10][11][12][13] and authoritarian-leaning.[10][14]

The pink tide was followed by the conservative wave, a political phenomenon that emerged in the mid-2010s in South America as a direct reaction to the pink tide. However, the pink tide saw a resurgence in 2018–19 after successive electoral victories of left-wing and centre-left candidates in Mexico, Panama, and Argentina.[15][16]

Background

During the Cold War, a series of left-leaning governments were elected in Latin America. These governments faced coups sponsored by the United States government as part of its geostrategic interest in the region.[17][18][19][20] Among these were the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, 1964 Brazilian coup d'état, 1973 Chilean coup d'état and 1976 Argentine coup d'état. All of these coups were followed by United States-backed and sponsored right-wing military dictatorships as part of the United States government's Operation Condor.[18][19][20]

These authoritarian regimes committed several human rights violations including illegal detentions of political opponents, suspects of be one and/or their families, tortures, disappearances and child trafficking.[21][22] As these regimes started to decline due to international pressure, internal outcry in the United States from the population due to the involvement in the atrocities forced Washington to relinquish its support for them. New democratic processes began during the late 1970s and up to the early 1990s.[23]

With the exception of Costa Rica, essentially all Latin American countries had at least one experience with a United States-supported dictator:[24] Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, the Somoza family in Nicaragua, Tiburcio Carias Andino in Honduras, Carlos Castillo Armas in Guatemala, Hugo Banzer in Bolivia, Juan María Bordaberry in Uruguay, Jorge Rafael Videla in Argentina, Augusto Pinochet in Chile, Alfredo Stroessner in Paraguay, François Duvalier in Haiti, Artur da Costa e Silva and his successor Emílio Garrastazu Médici in Brazil and Marcos Pérez Jiménez in Venezuela, which caused a strong anti-American sentiment in wide sectors of the population.[25][26][27][28]

History

Rise of the left: 1990s and 2000s

Following the third wave of democratization in the 1980s, the institutionalization of electoral competition in Latin America opened up the possibility for the left to ascend to power. For much of the region's history, formal electoral contestation excluded leftist movements, first through limited suffrage and later through military intervention and repression during the second half of the 20th century.[29] The collapse of the Soviet Union changed the geopolitical environment as many revolutionary movements vanished and the left embraced the core tenets of capitalism. As a result, the United States no longer perceived leftist governments as a security threat, creating a political opening for the left.[30]

In the 1990s, the left exploited this opportunity to solidify their base, run for local offices and gain experience governing on the local level. At the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, the region's initial unsuccessful attempts with the neoliberal policies of privatization, cuts in social spending and foreign investment left countries with high levels of unemployment, inflation and rising inequality.[31] The left's social platforms, which were centered on economic change and redistributive policies, offered an attractive alternative that mobilized large sectors of the population across the region who voted leftist leaders into office.[32]

.jpg)

The pink tide was led by Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, who was elected into the presidency in 1998.[33] According to Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a pink tide president herself, Chávez of Venezuela (inaugurated 1999), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva of Brazil (inaugurated 2003) and Evo Morales of Bolivia (inaugurated 2006) were "the three musketeers" of the left in South America.[34] National policies among the left in Latin America are divided between the styles of Chávez and Lula as the latter not only focused on those affected by inequality, but also catered to private enterprises and global capital.[35]

Commodities boom and growth

With the difficulties facing emerging markets across the world at the time, Latin Americans turned away from liberal economics and elected leftist leaders who had recently turned toward more democratic processes.[36] The popularity of such leftist governments relied upon by their ability to use the 2000s commodities boom to initiate populist policies,[37][38] such as those used by the Bolivarian government in Venezuela.[39] According to Daniel Lansberg, this resulted in "high public expectations in regard to continuing economic growth, subsidies, and social services".[38] With China becoming a more industrialized nation at the same time and requiring resources for its growing economy, it took advantage of the strained relations with the United States and partnered with the leftist governments in Latin America.[37][40] South America in particular initially saw a drop in inequality and a growth in its economy as a result of Chinese commodity trade.[40]

As the prices of commodities lowered into the 2010s, coupled with overspending with little savings by pink tide governments, policies became unsustainable and supporters became disenchanted, eventually leading to the rejection of leftist governments.[38][41] Analysts state that such unsustainable policies were more apparent in Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela,[40][41] who received Chinese funds without any oversight.[40][42] As a result, some scholars have stated that the pink tide's rise and fall was "a byproduct of the commodity cycle's acceleration and decadence".[37]

End of commodity boom and decline: 2010s

_(cropped_2).jpg)

Chávez, who was seen as having "dreams of continental domination", was determined to be a threat to his own people according to Michael Reid in American magazine, Foreign Affairs, with his influence reaching a peak in 2007.[43] The interest in Chávez waned after his dependence on oil revenue led Venezuela into an economic crisis and as he grew increasingly authoritarian.[43] The death of Chávez in 2013 left the most radical wing without a clear leader as Nicolás Maduro did not have the international influence of his predecessor. By the mid-2010s, Chinese investment in Latin America had also begun to decline,[40] especially following the 2015–2016 Chinese stock market crash.

In 2015, the shift away from the left became more pronounced in Latin America, with The Economist saying the pink tide had ebbed[44] and Vice News stating that 2015 was "The Year the 'Pink Tide' Turned".[34] By 2016, the decline of the pink tide saw an emergence of a "new right" in Latin America,[45] with The New York Times stating "Latin America's leftist ramparts appear to be crumbling because of widespread corruption, a slowdown in China's economy and poor economic choices", with the newspaper elaborating that leftist leaders did not diversify economies, had unsustainable welfare policies and disregarded democratic behaviors.[46] In mid-2016, the Harvard International Review stated that "South America, a historical bastion of populism, has always had a penchant for the left, but the continent's predilection for unsustainable welfarism might be approaching a dramatic end".[6]

International policies

Some pink tide governments, such as Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela, allegedly ignored international sanctions against Iran, allowing the Iranian government access to funds bypassing sanctions as well as resources such as uranium for the Iranian nuclear program.[47]

Corruption

On 12 July 2017, former Brazilian President Lula was convicted of money laundering and passive corruption, defined in Brazilian criminal law as the receipt of a bribe by a civil servant or government official. He was sentenced to nine years and six months in prison by judge Sérgio Moro.[48][49] Investigations later revealed that Lula pressured Odebrecht to pay millions of dollars toward the presidential campaign of the leftist Peruvian President Ollanta Humala.[50] On 7 April 2018, Lula turned himself in and began serving his jail sentence. On 9 June 2019, The Intercept released a trove of documents that showed Judge Sergio Moro acted politically in his ruling. Jair Bolsonaro later appointed him The Minister of Justice and Public Security.

In December 2017, Ecuadorian Vice President Jorge Glas was removed from office and sentenced to six years in prison after being involved with receiving over $13.5 million in bribes during the Odebrecht scandal.[51]

Economy and social development

Morales's government was praised internationally for its reduction of poverty, economic growth[52] and the improvement of indigenous, women[53] and LGBTI rights[54] in the very traditionally-minded Bolivian society.

Before Lula's election, Brazil suffered from one of the highest rates of poverty in the Americas, with the infamous favelas known internationally for its levels of extreme poverty, malnutrition and health problems. Extreme poverty was also a problem in rural areas. During Lula's presidency several social programs like Zero Hunger (Fome Zero) were praised internationally for reducing hunger in Brazil,[55] poverty and inequality while also improving the health and education of the population.[55][56] Around 29 million people became middle class during Lula's eight years tenure.[56] During Lula's government, Brazil became an economic power and member of BRICS.[55][56] Lula ended his tenure with 80% approval ratings.[57]

Economist from the University of Illinois[58] Rafael Correa was elected as President of Ecuador in the 2006 presidential election following the harsh economic crisis and social turmoil that caused right-wing Lucio Gutiérrez resignation as President. Correa, a practicing Catholic influenced by liberation theology,[58] was pragmatic in his economical approach in a similar manner to Morales in Bolivia[33] and Ecuador soon experienced a non-precedent economic growth that bolstered Correa's popularity to the point that he was the most popular president of the Americas' for several years in a row,[58] with an approval rate between 60 and 85%.[59]

Lugo's government was praised for its social reforms, including investments in low-income housing,[60] the introduction of free treatment in public hospitals,[61][62] the introduction of cash transfers for Paraguay's most impoverished citizens[63] and indigenous rights.[64]

Some of the initial results after the first pink tide governments were elected in Latin America included a reduction in the income gap,[5] unemployment, extreme poverty,[5] malnutrition and hunger[2][65] and rapid increase in literacy.[2] The decrease in these indicators during the same period of time happened faster than in non-Pink Tide governments.[66]

Countries like Ecuador,[67][68] El Salvador, Nicaragua[69] and Costa Rica[70] experienced notable economic growth during this period whilst Bolivia and El Salvador both saw a notable reduction in poverty according to the World Bank.[71][72]

Economic hardships occurred in countries such as Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela as oil and commodity prices declined and according to analysts because of their unsustainable policies.[40][41][73] In regard to the economic situation, President of Inter-American Dialogue Michael Shifter stated: "The United States–Cuban Thaw occurred with Cuba reapproaching the United States when Cuba's main international partner, Venezuela, began experiencing economic hardships".[74][75]

Political outcome

Following the initiation of the pink tide's policies, the relationship between both left-leaning and right-leaning governments and the public changed.[76] As leftist governments took power in the region, rising commodity prices funded their welfare policies, which lowered inequality and assisted indigenous rights.[76] The overspending of leftist governments in the 2000s resulted in the election of more liberal governments in the 2010s by citizens in the region seeking a sustainable economy, which required potential progressive politicians to reevaluate their policies.[76] However, such advancements changed the location of Latin America's center of the political spectrum,[77] forcing right-wing candidates and succeeding governments to adopt more socially-conscious administrations.[76]

Under the Obama administration, which held a less interventionist approach to the region after recognizing that interference would only boost the popularity of populist pink tide leaders like Chávez, Latin American approval of the United States began to improve as well.[78] By the mid-2010s, "negative views of China were widespread" due to the substandard conditions of Chinese goods, unjust professional actions, cultural differences, damage to the Latin American environment and perceptions of Chinese interventionism.[79]

Resurgence

During 2018 and 2019, two new countries entered the Pink Tide, Mexico with the electoral victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in the 2018 Mexican general election and Laurentino Cortizo in the 2019 Panamanian general election, whilst incumbent right-wing president Mauricio Macri of Argentina lost against left-wing Peronist Alberto Fernández alongside Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as running mate in the 2019 Argentine general election and in Colombia the ruling right-wing party of President Iván Duque and Alvaro Uribe faced a notorious defeat at the 2019 regional elections.[80]

A series of very violent protests against austerity measures and income inequality scattered throughout Latin America including the 2019 Chilean protests, 2018–19 Haitian protests and the 2019 Ecuadorian protests, whilst in Honduras, anti-government protest requesting the resignation of Juan Orlando Hernández for the accusations of narcotics connections against him also spread.

Term

As a term, the pink tide had become prominent in contemporary discussion of Latin American politics in the early 21st century. Origins of the term may be linked to a statement by Larry Rohter, a New York Times reporter in Montevideo who characterized the 2004 presidential election of Tabaré Vázquez as leader of Uruguay as "not so much a red tide [...] as a pink one".[13] The term seems to be a play on words based on red tide (a biological phenomenon rather than a political one) with red – a color long associated with communism – being replaced with the lighter tone of pink to indicate the more moderate socialist ideas that gained strength.[81]

Despite the presence of a number of Latin American governments which professed to embracing a leftist ideology, it is difficult to categorize Latin American states "according to dominant political tendencies, like a red-blue post-electoral map of the United States".[81] According to the Institute for Policy Studies, a leftist think-tank based in Washington, D.C.:

- While this political shift was difficult to quantify, its effects were widely noticed. According to the Institute for Policy Studies, 2006 meetings of the South American Summit of Nations and the Social Forum for the Integration of Peoples demonstrated that certain discussions that used to take place on the margins of the dominant discourse of neoliberalism, now moved to the center of public debate.[81]

In the 2011 book The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience, Isbester states:

Ultimately, the term "the Pink Tide" is not a useful analytical tool as it encompasses too wide a range of governments and policies. It includes those actively overturning neoliberalism (Chávez and Morales), those reforming neoliberalism (Lula), those attempting a confusing mixture of both (the Kirchners and Correa), those having rhetoric but lacking the ability to accomplish much (Toledo), and those using anti-neoliberal rhetoric to consolidate power through non-democratic mechanisms (Ortega).[77]

Reception

In 2006, The Arizona Republic recognized the growing pink tide, stating: "A couple of decades ago, the region, long considered part of the United States' backyard, was basking in a resurgence of democracy, sending military despots back to their barracks", further recognizing the "disfavor" with the United States and the concerns of "a wave of nationalist, leftist leaders washing across Latin America in a 'pink tide'" among United States officials.[82]

A 2007 report from the Inter Press Service news agency said how "elections results in Latin America appear to have confirmed a left-wing populist and anti-U.S. trend – the so-called "pink tide" – which [...] poses serious threats to Washington's multibillion-dollar anti-drug effort in the Andes".[83]

In 2014, Albrecht Koschützke and Hajo Lanz, directors of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation for Central America, discussed the "hope for greater social justice and a more participatory democracy" following the election of leftist leaders, though the foundation recognized that such elections "still do not mean a shift to the left", but that they are "the result of an ostensible loss of prestige from the right-wing parties that have traditionally ruled".[84]

Head of the states and governments

Presidents

Below are left-wing and centre-left presidents elected in Latin America since 1995:

- Néstor Kirchner* (2003–2007)

- Cristina Fernández de Kirchner* (2007–2015)

- Alberto Fernández* (2019–present)

- Evo Morales (2006–2019)

- Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva* (2003–2011)

- Dilma Rousseff* (2011–2016)

- Ricardo Lagos* (2000–2006)

- Michelle Bachelet* (2006–2010; 2014–2018)

- Leonel Fernández* (1996–2000; 2004–2012)

- Danilo Medina* (2012–2020)[85]

- Luis Abinader* (2020–present)

- Rafael Correa (2007–2017)

- Mauricio Funes* (2009–2014)

- Salvador Sánchez Cerén* (2014–2019)

.svg.png)

- Manuel Zelaya (2006–2009)[86]

- Andrés Manuel López Obrador* (2018–present)

- Daniel Ortega (1985–1990; 2007–present)

- Martín Torrijos Espino* (2004–2009)

- Laurentino Cortizo* (2019–present)

- Fernando Lugo* (2008–2012)

- Ollanta Humala* (2011–2016)

- Tabaré Vázquez* (2005–2010; 2015–2020)

- José Mujica* (2010–2015)

- Hugo Chávez (1999–2013)

- Nicolás Maduro‡ (2013–present)

Note that centre-left presidents are marked with * while Venezuela is under a presidential crisis taking place with ‡.

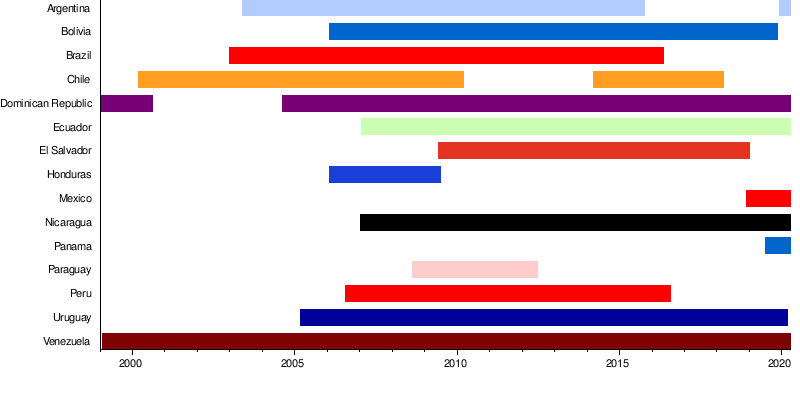

Timeline

The timeline shows periods where a left-wing leader governed over a particular country, beginning with Hugo Chávez in 1999:

See also

References

- Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (January–April 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. 38 (1): 11–53. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100001.

No matter the shades of pink in the Latin American 'pink tide', and recalling that political change was not the norm for the whole region during that period, there seems to be greater agreement when it comes to explaining its emergence. In terms of this canonical interpretation, the left turn should be understood as a feature of general redemocratisation in the region, which is widely regarded as an inevitable result of the high levels of inequality in the region.

- Abbott, Jared. "Will the Pink Tide Lift All Boats? Latin American Socialisms and Their Discontents". Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Oikonomakis, Leonidas (16 March 2015). "Europe's pink tide? Heeding the Latin American experience". Retrieved 5 April 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "COHA Statement on the Ongoing Stress in Venezuela" Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- Fernandes Pimenta, Gabriel; Casas V M Arantes, Pedro (2014). "Rethinking Integration in Latin America: The "Pink Tide" and the Post-Neoliberal Regionalism" (PDF). FLACSO. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

In general, one must say that these governments have as defining common feature ample and generous social inclusion policies that link effectively for social investments that certainly had an impact on regional social indicators (LIMA apud SILVA, 2010a). In this sense, so far, all of these countries had positive improvements. As a result, it was observed the reduction in social inequality, as well as the reduction of poverty and other social problems (SILVA, 2010a)

- Lopes, Arthur (Spring 2016). "¿Viva la Contrarrevolución? South America's Left Begins to Wave Goodbye". Harvard International Review. 37 (3): 12–14.

South America, a historical bastion of populism, has always had a penchant for the left, but the continent's predilection for unsustainable welfarism might be approaching a dramatic end. ... This "pink tide" also included the rise of populist ideologies in some of these countries, such as Kirchnerismo in Argentina, Chavismo in Venezuela, and Lulopetismo in Brazil.

- da Cruz, Jose de Arimateia (2015). "Strategic Insights: From Ideology to Geopolitics: Russian Interests in Latin America". Current Politics and Economics of Russia, Eastern and Central Europe. Nova Science Publishers. 30 (1/2): 175–185.

- Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (Jan–Apr 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. 38 (1): 11–53. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100001.

... one finds as many local left-leaning governments as there are countries making up the so-called left turn, because they emerged from distinct institutional settings ... espoused distinct degrees of anti-Americanism ...

CS1 maint: date format (link) - Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (Jan–Apr 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. 38 (1): 11–53. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100001.

The wrong left, by contrast, was said to be populist, old-fashioned, and irresponsible ...

CS1 maint: date format (link) - Isbester, Katherine (2011). The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1442601802.

... the populous of Latin America are voting in the Pink Tide governments that struggle with reform while being prone to populism and authoritarianism.

- "The many stripes of anti-Americanism". Boston Globe. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "South America's leftward sweep". BBC News. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- "Latin America's 'pragmatic' pink tide" Archived 16 May 2016 at the Portuguese Web Archive Pittsburgh Tribune-Herald.

- Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (Jan–Apr 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. 38 (1): 11–53. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100001.

However, these analytical and taxonomic efforts often led to new dichotomies ... democrats and authoritarians ...

- Bello (5 September 2019). "Will South America's "pink tide" return?". The Economist. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- García Linera, Álvaro (20 October 2019). "Latin America's Pink Tide Isn't Over". Jacobin. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- "Los secretos de la guerra sucia continental de la dictadura" (The secrets of the continental dirty war of the dictators), Clarin, 24 March 2006 (in Spanish).

- McSherry, J. Patrice (2011). "Chapter 5: "Industrial repression" and Operation Condor in Latin America". In Esparza, Marcia; Henry R. Huttenbach; Daniel Feierstein (eds.). State Violence and Genocide in Latin America: The Cold War Years (Critical Terrorism Studies). Routledge. p. 107. ISBN 978-0415664578.

- Greg Grandin (2011). The Last Colonial Massacre: Latin America in the Cold War. University of Chicago Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0226306902.

- Walter L. Hixson (2009). The Myth of American Diplomacy: National Identity and U.S. Foreign Policy. Yale University Press. p. 223. ISBN 0300151314.

- Ben Norton (28 May 2015). "Victims of Operation Condor, by Country". Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Society, National Geographic (17 December 2013). "Archives of Terror Discovered". National Geographic. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Klein, Naomi (2007). The Shock Doctrine. New York: Picador. p. 126. ISBN 978-0312427993.

- Stanley, Ruth (2006). "Predatory States. Operation Condor and Covert War in Latin America/When States Kill. Latin America, the U.S., and Technologies of Terror". Journal of Third World Studies. Retrieved 24 October 2007.

- "CIA acknowledges involvement in Allende's overthrow, Pinochet's rise". BBC News. 19 September 2000. Archived from the original (– search) on 8 November 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "World Publics Reject US Role as the World Leader" (PDF). The Chicago Council on Public Affairs. April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 April 2013.

- "Argentina: Opinion of the United States". Pew Research Center. 2012.

- "Argentina: Opinion of Americans (Unfavorable) – Indicators Database". Pewglobal.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Levitsky, Steven; Roberts, Kenneth. "The Resurgence of the Latin American Left" (PDF). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Levitsky, Ibid.

- Rodriguez, Robert G. (2014). "Re-Assessing the Rise of the Latin American Left" (PDF). The Midsouth Political Science Review. Arkansas Political Science Association. 15 (1): 59. ISSN 2330-6882.

- Levitsky, Ibid.

- McMaken, Ryan (2016). Latin America's Pink Tide Crashes On The Rocks. Mises Institute.

- Noel, Andrea (29 December 2015). "The Year the 'Pink Tide' Turned: Latin America in 2015". Vice News. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Miroff, Nick (28 January 2014). "Latin America's political right in decline as leftist governments move to middle". The Guardian.

- Reid, Michael (September–October 2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94 (5): 45–53.

... half a dozen countries, led by Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, formed a hard-left anti-American bloc with authoritarian tendencies...

- Lopes, Dawisson Belém; de Faria, Carlos Aurélio Pimenta (Jan–Apr 2016). "When Foreign Policy Meets Social Demands in Latin America". Contexto Internacional (Literature review). Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro. 38 (1): 11–53. doi:10.1590/S0102-8529.2016380100001.

The fate of Latin America's left turn has been closely associated with the commodities boom (or supercycle) of the 2000s, largely due to rising demand from emerging markets, notably China.

- Lansberg-Rodríguez, Daniel (Fall 2016). "Life after Populism? Reforms in the Wake of the Receding Pink Tide". Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. Georgetown University Press. 17 (2): 56–65. doi:10.1353/gia.2016.0025.

- Fisher, Max; Taub, Amanda (1 April 2017). "How Does Populism Turn Authoritarian? Venezuela Is a Case in Point". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94 (5): 45–53.

As China industrialized in the first decade of the century, its demand for raw materials rose, pushing up the prices of South American minerals, fuels, and oilseeds. From 2000 to 2013, Chinese trade with Latin America rocketed from $12 billion to over $275 billion. ... Its loans have helped sustain leftist governments pursuing otherwise unsustainable policies in Argentina, Ecuador, and Venezuela, whose leaders welcomed Chinese aid as an alternative to the strict conditions imposed by the International Monetary Fund or the financial markets. ... The Chinese-fueled commodity boom, which ended only recently, lifted Latin America to new heights. The region – and especially South America – enjoyed faster economic growth, a steep fall in poverty, a decline in extreme income inequality, and a swelling of the middle class.

- "Americas Economy: Is the "Pink Tide" Turning?". The Economist Intelligence Unit Ltd. 8 December 2015.

In 2004-13 many pink tide countries benefited from strong economic growth, with exceptionally high commodities prices driving exports, owing to robust demand from China. These conditions brought regional growth ... However, the negative impact of expansionary policy on inflation, fiscal deficits and non-commodity exports in many countries soon began to prove that this boom period was unsustainable, even before international oil prices plummeted alongside prices of other key commodities at the end of 2014. ... These challenging economic conditions have exposed the negative consequences of years of policy mismanagement in various countries, most notably in Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela.

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues. Brookings Institution: 5–6.

[China] promised to impose no political conditions on its economic and technical assistance, in contrast to the usual strings-attached approach from Washington, Europe, and the international financial institutions, and committed to debt cancellation 'as China's ability permits.' ... As one South American diplomat put it, given the choice between the onerous conditions of the neoliberal Washington consensus and the no-strings-attached largesse of the Chinese, elevating relations with Beijing was a no-brainer.

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94 (5): 45–53.

Washington's trade strategy was to contain Chávez and his dreams of continental domination ... the accurate assessment that Chávez was a threat to his own people. ... Chávez's regional influence peaked around 2007. His regime lost appeal because of its mounting authoritarianism and economic difficulties.

- "The ebbing of the pink tide". The Economist.

- de Oliveira Neto, Claire; Howat Berger, Joshua (1 September 2016). "Latin America's 'pink tide' ebbs to new low in Brazil". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- "The Left on the Run in Latin America". The New York Times. 23 May 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues. Brookings Institution: 11–12.

Countries that are part of the so-called "pink tide" in Latin America, most notably Venezuela, have tended to defy international sanctions and partner with Iran. Venezuela's economic ties to Iran reportedly have helped Tehran to skirt international sanctions through the establishment of joint companies and nancial entities. Other ALBA countries such as Ecuador and Bolivia have also been important strategic partners to Iran, allowing the regime to extract uranium needed for its nuclear program.

- "Lula é condenado a nove anos de prisão". Veja (in Portuguese). Grupo Abril. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- Brooks, Brad (12 July 2017). "Brazil's Former President Found Guilty Of Corruption". Huffington Post. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- EC, Redacción (2017-12-14). "Las claves de la prisión preventiva contra Ollanta Humala y Nadine Heredia". El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- "Ecuador's VP Jorge Glas jailed for six years over Odebrecht kickbacks". Deutsche Welle. 14 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- "Evo Morales". Britannica. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Schipani, Andres (11 February 2010). "Bolivian women spearhead Morales revolution". BBC. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Tegel, Simeon (17 July 2016). "A surprising move on LGBT rights from a 'macho' South American president". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "Introduction: Lula's Legacy in Brazil". Nacla. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Kingstone, Steve (2010). "How President Lula changed Brazil". BBC. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Phillips, Don (17 October 2017). "Accused of corruption, popularity near zero – why is Temer still Brazil's president?". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- North, James (4 June 2015). "Why Ecuador's Rafael Correa Is One of Latin America's Most Popular Leaders". The Nation. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- Miroff, Nick (15 March 2014). "Ecuador's popular, powerful president Rafael Correa is a study in contradictions". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "Paraguay" (PDF).

- "Paraguay: Mixed Results for Lugo's First 100 Days". Inter Press Service. 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "Chap 10".

- "The boy and the bishop". The Economist. 30 April 2009.

- "The Bishop of the Poor: Paraguay's New President Fernando Lugo Ends 62 Years of Conservative Rule". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- "Tres tenues luces de esperanza Las fuerzas de izquierda cobran impulso en tres países centroamericanos" (PDF). Nueva Sociedad. 2014. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Ystanes, Margit; Åsedotter Strønen, Iselin (25 October 2017). The Social Life of Economic Inequalities in Contemporary Latin America. ISBN 978-3319615363.

[reduction of inequality gap] On average, the decrease was much slower for countries not under the Pink Tide governments (Cornia 2012). In light of this, it is clear that the Pink Tide governments positively impacted the living standards of the working classes.

- "Boom económico en Ecuador". El Telégrafo. Archived from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- World Bank (2014). "Ecuador". Retrieved 5 April 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - World Bank. "Nicaragua". Retrieved 5 April 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - OECD. "Costa Rica – Economic forecast summary (November 2016)". Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- World Bank (2015). "Reducing poverty in Bolivia comes down to two words: rural development". Retrieved 5 April 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - World Bank. "El Salvador". Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- Partlow, Joshua; Caselli, Irene (23 November 2015). "Does Argentina's pro-business vote mean the Latin American left is dead?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- "Why the United States and Cuba are cosying up". The Economist. 29 May 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Usborne, David (4 December 2015). "Venezuela's ruling socialists face defeat at polls". The Independent. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Eulich, Whitney (4 April 2017). "Even as South America tilts right, a leftist legacy stands strong". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Isbester, Katherine (2011). The Paradox of Democracy in Latin America: Ten Country Studies of Division and Resilience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1442601802.

- Reid, Michael (2015). "Obama and Latin America: A Promising Day in the Neighborhood". Foreign Affairs. 94: 45–53.

Officials in the Obama administration argued that it was counterproductive to publicly criticize Chávez, since doing so failed to change his behavior and merely allowed him to pose as a popular campaigner against American imperialism ... According to Latinobarómetro, a polling organization, an average of 69 percent of respondents in the region held a favorable view of the United States in 2013, up from 58 percent in 2008. ... In today's Latin America, it is hard to imagine that more confrontational policies would have achieved better results, ... the United States is no longer the only game in town in much of Latin America, bullying is often ineffective. ... circumstances in the region are becoming increasingly favorable for the United States.

- Piccone, Ted (November 2016). "The Geopolitics of China's Rise in Latin America". Geoeconomics and Global Issues. Brookings Institution: 7–8.

Meanwhile, recent public opinion polls of Latin Americans reveal wavering attitudes toward China's influence in the region ... opinions of China as a model and as a rising power declined between 2012 and 2014. ... the authors concluded that negative views of China were widespread, mainly regarding the poor quality of Chinese goods, unfair business practices, incompatible language and culture, unsustainable development policies harmful to the environment, and fears of Chinese economic and demographic domination in international relations.

- "Uribe reconoce derrota del Centro Democrático en las regionales". El Tiempo. 27 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 September 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Institute for Policy Studies: Latin America's Pink Tide?

- "The Issue: A Changing Latin America: Fears of 'Pink Tide'". The Arizona Republic. 12 June 2006.

- "Challenges 2006–2007: A Bad Year for Empire". Archived 14 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Inter Press Service.

- "Tres tenues luces de esperanza Las fuerzas de izquierda cobran impulso en tres países centroamericanos" (PDF). Nueva Sociedad. 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2014.

- The Dominican Liberation Party in which both Dominican Presidents belong to has a centrist position.

- During his presidency, Zelaya was a member of the Liberal Party of Honduras.