Salzburg

Salzburg (Austrian: [ˈsaltsbʊʁk]; German: [ˈzaltsbʊʁk] (![]()

Salzburg | |

|---|---|

.jpg)   .jpg) From top, left to right: view of Hohensalzburg Fortress, University of Salzburg in front of the Salzach, with Nonnberg Abbey in the background, Salzburg Cathedral, Roittner-Durchhaus, Getreidegasse | |

_COA.svg.png) Coat of arms | |

Salzburg Location within Austria  Salzburg Salzburg (Austria) | |

| Coordinates: 47°48′0″N 13°02′0″E | |

| Country | |

| State | Salzburg |

| District | Statutory city |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Harald Preuner (ÖVP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 65.65 km2 (25.35 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 424 m (1,391 ft) |

| Population (1 June 2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 156,872 |

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 5020 |

| Area code | 0662 |

| Vehicle registration | S |

| Website | www |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv, vi |

| Reference | 784 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th session) |

| Area | 236 ha |

| Buffer zone | 467 ha |

The town is located on the site of the former Roman settlement of Iuvavum. Salzburg was founded as an episcopal see in 696 and became a seat of the archbishop in 798. Its main sources of income were salt extraction and trade and, at times, gold mining. The fortress of Hohensalzburg, one of the largest medieval fortresses in Europe, dates from the 11th century. In the 17th century, Salzburg became a centre of the Counter-Reformation, where monasteries and numerous Baroque churches were built.

Salzburg's historic centre (German: Altstadt) is thus renowned for its Baroque architecture and is one of the best-preserved city centres north of the Alps, with 27 churches. It was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. The city has three universities and a large population of students. Tourists also visit Salzburg to tour the historic centre and the scenic Alpine surroundings. Salzburg was the birthplace of the 18th-century composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Because of its history, culture, and attractions, Salzburg has been labeled Austria's "most inspiring city."[8]

History

Antiquity to the High Middle Ages

Traces of human settlements have been found in the area, dating to the Neolithic Age. The first settlements in Salzburg continuous with the present were apparently by the Celts around the 5th century BC.

Around 15 BC the Roman Empire merged the settlements into one city. At this time, the city was called "Juvavum" and was awarded the status of a Roman municipium in 45 AD. Juvavum developed into an important town of the Roman province of Noricum. After the Norican frontier's collapse, Juvavum declined so sharply that by the late 7th century it nearly became a ruin.[9]

The Life of Saint Rupert credits the 8th-century saint with the city's rebirth. When Theodo of Bavaria asked Rupert to become bishop c. 700, Rupert reconnoitered the river for the site of his basilica. Rupert chose Juvavum, ordained priests, and annexed the manor of Piding. Rupert named the city "Salzburg". He travelled to evangelise among pagans.

The name Salzburg means "Salt Castle" (Latin: Salis Burgium). The name derives from the barges carrying salt on the River Salzach, which were subject to a toll in the 8th century as was customary for many communities and cities on European rivers. Hohensalzburg Fortress, the city's fortress, was built in 1077 by Archbishop Gebhard, who made it his residence.[10] It was greatly expanded during the following centuries.

Independence

Independence from Bavaria was secured in the late 14th century. Salzburg was the seat of the Archbishopric of Salzburg, a prince-bishopric of the Holy Roman Empire. As the Reformation movement gained steam, riots broke out among peasants in the areas in and around Salzburg. The city was occupied during the German Peasants' War, and the Archbishop had to flee to the safety of the fortress.[11] It was besieged for three months in 1525.

Eventually, tensions were quelled, and the city's independence led to an increase in wealth and prosperity, culminating in the late 16th to 18th centuries under the Prince Archbishops Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau, Markus Sittikus, and Paris Lodron. It was in the 17th century that Italian architects (and Austrians who had studied the Baroque style) rebuilt the city centre as it is today along with many palaces.[12]

Modern era

Religious conflict

On 31 October 1731, the 214th anniversary of the 95 Theses, Archbishop Count Leopold Anton von Firmian signed an Edict of Expulsion, the Emigrationspatent, directing all Protestant citizens to recant their non-Catholic beliefs. 21,475 citizens refused to recant their beliefs and were expelled from Salzburg. Most of them accepted an offer by King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia, travelling the length and breadth of Germany to their new homes in East Prussia.[13] The rest settled in other Protestant states in Europe and the British colonies in America.

Illuminism

In 1772–1803, under archbishop Hieronymus Graf von Colloredo, Salzburg was a centre of late Illuminism. Colloredo is known for being one of the main employers of Mozart. He often had several arguments with Mozart he dismissed him by saying, “Soll er doch gehen, ich brauche ihn nicht!” (He should just go then; I don’t need him!) Mozart would leave Salzburg for Vienna in 1781 with his family including his father Leopold staying back as he and Colloredo had a close relationship.

Electorate of Salzburg

In 1803, the archbishopric was secularised by Emperor Napoleon; he transferred the territory to Ferdinando III of Tuscany, former Grand Duke of Tuscany, as the Electorate of Salzburg.

Austrian annexation of Salzburg

In 1805, Salzburg was annexed to the Austrian Empire, along with the Berchtesgaden Provostry.

Salzburg under Bavarian rule

In 1809, the territory of Salzburg was transferred to the Kingdom of Bavaria after Austria's defeat at Wagram.

Division of Salzburg and annexation by Austria and Bavaria

After the Congress of Vienna with the Treaty of Munich (1816), Salzburg was definitively returned to Austria, but without Rupertigau and Berchtesgaden, which remained with Bavaria. Salzburg was integrated into the Province of Salzach and Salzburgerland was ruled from Linz.[14]

In 1850, Salzburg's status was restored as the capital of the Duchy of Salzburg, a crownland of the Austrian Empire. The city became part of Austria-Hungary in 1866 as the capital of a crownland of the Austrian Empire. The nostalgia of the Romantic Era led to increased tourism. In 1892, a funicular was installed to facilitate tourism to Hohensalzburg Fortress[15]

20th century

First Republic

Following World War I and the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Salzburg, as the capital of one of the Austro-Hungarian territories, became part of the new German Austria. In 1918, it represented the residual German-speaking territories of the Austrian heartlands. This was replaced by the First Austrian Republic in 1919, after the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919).

Annexation by the Third Reich

The Anschluss (the occupation and annexation of Austria, including Salzburg, into the Third Reich) took place on 12 March 1938, one day before a scheduled referendum on Austria's independence. German troops moved into the city. Political opponents, Jewish citizens and other minorities were subsequently arrested and deported to concentration camps. The synagogue was destroyed. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union, several POW camps for prisoners from the Soviet Union and other enemy nations were organized in the city.

During the Nazi occupation, a Romani camp was built in Salzburg-Maxglan. It was an Arbeitserziehungslager (work 'education' camp), which provided slave labour to local industry. It also operated as a Zwischenlager (transit camp), holding Roma before their deportation to German camps or ghettos in German-occupied territories in eastern Europe.[16]

World War II

Allied bombing destroyed 7,600 houses and killed 550 inhabitants. Fifteen air strikes destroyed 46 percent of the city's buildings, especially those around Salzburg railway station. Although the town's bridges and the dome of the cathedral were destroyed, much of its Baroque architecture remained intact. As a result, Salzburg is one of the few remaining examples of a town of its style. American troops entered the city on 5 May 1945 and it became the centre of the American-occupied area in Austria. Several displaced persons camps were established in Salzburg—among them Riedenburg, Camp Herzl (Franz-Josefs-Kaserne), Camp Mülln, Bet Bialik, Bet Trumpeldor, and New Palestine.

Present day

After World War II, Salzburg became the capital city of the Federal State of Salzburg (Land Salzburg) and saw the Americans leave the area once Austria had signed a 1955 treaty reestablishing the country as a democratic and independent nation and subsequently declared its perpetual neutrality. On 27 January 2006, the 250th anniversary of the birth of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, all 35 churches of Salzburg rang their bells after 8:00 p.m. (local time) to celebrate the occasion. Major celebrations took place throughout the year.

As of 2017 Salzburg had a GDP per capita of €46,100, which was greater than the average for Austria and for most European countries.[17]

Geography

Salzburg is on the banks of the River Salzach, at the northern boundary of the Alps. The mountains to Salzburg's south contrast with the rolling plains to the north. The closest alpine peak, the 1,972‑metre-high Untersberg, is less than 16 kilometres (10 miles) from the city centre. The Altstadt, or "old town", is dominated by its baroque towers and churches and the massive Hohensalzburg Fortress. This area is flanked by two smaller hills, the Mönchsberg and Kapuzinerberg, which offer green relief within the city. Salzburg is approximately 150 km (93 mi) east of Munich, 281 km (175 mi) northwest of Ljubljana, Slovenia, and 300 km (186 mi) west of Vienna. Salzburg has about the same latitude of Seattle.

Climate

Salzburg is part of the temperate zone. The Köppen climate classification specifies the climate as a humid continental climate (Dfb), however, with the −3 °C (27 °F) isotherm for the coldest month, Salzburg can be classified as having four-season oceanic climate with significant temperature differences between seasons. Due to the location at the northern rim of the Alps, the amount of precipitation is comparatively high, mainly in the summer months. The specific drizzle is called Schnürlregen in the local dialect. In winter and spring, pronounced foehn winds regularly occur.

| Climate data for Salzburg-Flughafen (LOWS) 1981–2010, extremes 1874–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.8 (69.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

30.3 (86.5) |

34.1 (93.4) |

35.7 (96.3) |

37.7 (99.9) |

36.6 (97.9) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.1 (30.0) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.6 (40.3) |

8.9 (48.0) |

14.0 (57.2) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

9.4 (48.9) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

5.1 (41.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −30.4 (−22.7) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−27.7 (−17.9) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59 (2.3) |

53 (2.1) |

87 (3.4) |

78 (3.1) |

115 (4.5) |

151 (5.9) |

158 (6.2) |

164 (6.5) |

112 (4.4) |

73 (2.9) |

72 (2.8) |

72 (2.8) |

1,195 (47.0) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 23 (9.1) |

24 (9.4) |

18 (7.1) |

2 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

10 (3.9) |

24 (9.4) |

101 (40) |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 14:00) | 71.4 | 63.5 | 56.9 | 51.3 | 51.2 | 54.3 | 52.6 | 55.2 | 58.4 | 61.9 | 70.0 | 74.9 | 60.1 |

| Source 1: Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics[18][19][20][21][22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[23] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Salzburg Airport (1971–2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.3 (61.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

32.2 (90.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

37.7 (99.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

32.1 (89.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

37.7 (99.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

0.4 (32.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.4 (−13.7) |

−21.8 (−7.2) |

−21.6 (−6.9) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−8 (18) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−26.8 (−16.2) |

−26.8 (−16.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59.9 (2.36) |

54.7 (2.15) |

78.7 (3.10) |

83.1 (3.27) |

114.5 (4.51) |

154.8 (6.09) |

157.5 (6.20) |

151.3 (5.96) |

101.3 (3.99) |

72.6 (2.86) |

83.0 (3.27) |

72.8 (2.87) |

1,184.2 (46.62) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 24.0 (9.4) |

23.9 (9.4) |

21.7 (8.5) |

2.9 (1.1) |

0.1 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

12.1 (4.8) |

27.8 (10.9) |

112.5 (44.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.1 | 9.5 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 14.4 | 13.2 | 10.8 | 9.3 | 10.8 | 11.8 | 140.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 14:00) | 73.6 | 65.6 | 58.1 | 54.9 | 52.5 | 55.6 | 54.5 | 55.6 | 58.8 | 62.8 | 70.6 | 75.4 | 61.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 67.0 | 91.9 | 130.0 | 152.6 | 196.4 | 193.9 | 221.1 | 202.8 | 167.7 | 129.7 | 81.2 | 62.8 | 1,697.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 26.9 | 34.4 | 37.9 | 39.4 | 44.3 | 43.7 | 48.8 | 48.3 | 47.4 | 42.9 | 30.8 | 26.7 | 39.3 |

| Source: Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics[24] | |||||||||||||

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 27,858 | — |

| 1880 | 33,241 | +19.3% |

| 1890 | 38,081 | +14.6% |

| 1900 | 48,945 | +28.5% |

| 1910 | 56,423 | +15.3% |

| 1923 | 60,026 | +6.4% |

| 1934 | 69,447 | +15.7% |

| 1939 | 77,170 | +11.1% |

| 1951 | 102,927 | +33.4% |

| 1961 | 108,114 | +5.0% |

| 1971 | 129,919 | +20.2% |

| 1981 | 139,426 | +7.3% |

| 1991 | 143,978 | +3.3% |

| 2001 | 142,662 | −0.9% |

| 2011 | 145,367 | +1.9% |

| 2016 | 150,887 | +3.8% |

| Source: Statistik Austria[25] | ||

| Largest groups of foreign residents[26] | |

| Nationality | Population (1.1.2020) |

|---|---|

| 7,500 | |

| 5,240 | |

| 4,807 | |

| 2,756 | |

| 2,476 | |

| 2,422 | |

| 1,810 | |

| 1,581 | |

| 1,571 | |

| 1,128 | |

| 1,030 | |

In 2018, 31% of the total population is foreign born according to Statistik Austria.

Salzburg's official population significantly increased in 1935 when the city absorbed adjacent municipalities. After World War II, numerous refugees found a new home in the city. New residential space was constructed for American soldiers of the postwar occupation, and could be used for refugees when they left. Around 1950, Salzburg passed the mark of 100,000 citizens, and in 2016, it reached the mark of 150,000 citizens.

Architecture

2.jpg)

Romanesque and Gothic

The Romanesque and Gothic churches, the monasteries and the early carcass houses dominated the medieval city for a long time. The Cathedral of Archbishop Conrad of Wittelsbach was the largest basilica north of the Alps. The choir of the Franciscan Church, construction was begun by Hans von Burghausen and completed by Stephan Krumenauer, is one of the most prestigious religious gothic constructions of southern Germany. At the end of the Gothic era the Collegiate church "Nonnberg", Margaret Chapel in St. Peter's Cemetery, the St. George's Chapel and the stately halls of the "Hoher Stock" in Hohensalzburg Fortress were constructed.

Renaissance and baroque

Inspired by Vincenzo Scamozzi, Prince Archbishop Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau began to transform the medieval town to the architectural ideals of the late Renaissance. Plans for a massive cathedral by Scamozzi failed to materialize upon the fall of the archbishop. A second cathedral planned by Santino Solari rose as the first early Baroque church in Salzburg. It served as an example for many other churches in Southern Germany and Austria. Markus Sittikus and Paris von Lodron continued to rebuild the city with major projects such as Hellbrunn Palace, the prince archbishop's residence, the university buildings, fortifications, and many other buildings. Giovanni Antonio Daria managed by order of Prince Archbishop Guido von Thun the construction of the residential well. Giovanni Gaspare Zuccalli, by order of the same archbishop, created the Erhard and the Kajetan church in the south of the town. The city's redesign was completed with buildings designed by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, donated by Prince Archbishop Johann Ernst von Thun.

After the era of Ernst von Thun, the city's expansion came to a halt, which is the reason why there are no churches built in the Rococo style. Sigismund von Schrattenbach continued with the construction of "Sigmundstor" and the statue of holy Maria on the cathedral square. With the fall and division of the former "Fürsterzbistum Salzburg" (Archbishopric) to Upper Austria, Bavaria (Rupertigau) and Tyrol (Zillertal Matrei) began a long period of urban stagnancy. This era didn't end before the period of promoterism (Gründerzeit) brought new life into urban development. The builder dynasty Jakob Ceconi and Carl Freiherr von Schwarz filled major positions in shaping the city in this era.[27]

Classical modernism and post-war modernism

Buildings of classical modernism and in particular the post-war modernism are frequently encountered in Salzburg. Examples are the Zahnwurzen house (a house in the Linzergasse 22 in the right center of the old town), the "Lepi" (a public baths in Leopoldskron) (built 1964) and the original 1957 constructed congress centre of Salzburg, which was replaced by a new building in 2001. An important and famous example of architecture of this era is the 1960 opening of the Großes Festspielhaus by Clemens Holzmeister.

Contemporary architecture

Adding contemporary architecture to Salzburg's old town without risking its UNESCO World Heritage status is problematic. Nevertheless, some new structures have been added: the Mozarteum at the Baroque Mirabell Garden (Architecture Robert Rechenauer),[28] the 2001 Congress House (Architecture: Freemasons), the 2011 Unipark Nonntal (Architecture: Storch Ehlers Partners), the 2001 "Makartsteg" bridge (Architecture: HALLE1), and the "Residential and Studio House" of the architects Christine and Horst Lechner in the middle of Salzburg's old town (winner of the architecture award of Salzburg 2010).[29][30] Other examples of contemporary architecture lie outside the old town: the Faculty of Science building (Universität Salzburg – Architecture Willhelm Holzbauer) built on the edge of free green space, the blob architecture of Red Bull Hangar‑7 (Architecture: Volkmar Burgstaller[31]) at Salzburg Airport, home to Dietrich Mateschitz's Flying Bulls and the Europark Shopping Centre. (Architecture: Massimiliano Fuksas)

Districts

Salzburg has twenty-four urban districts and three extra-urban populations. Urban districts (Stadtteile):

Extra-urban populations (Landschaftsräume):

- Gaisberg

- Hellbrunn

- Heuberg

Main sights

Salzburg is a tourist favourite, with the number of visitors outnumbering locals by a large margin in peak times. In addition to Mozart's birthplace noted above, other notable places include:

Old Town

- Historic centre of the city of Salzburg, a World Heritage Site

- Baroque architecture, including many churches

- Salzburg Cathedral (Salzburger Dom)

- Franciscan Church (Franziskanerkirche)

- Holy Trinity Church (Dreifaltigkeitskirche)

- Kollegienkirche

- Nonnberg Abbey, a Benedictine monastery

- St Peter's Abbey with the Petersfriedhof

- Hohensalzburg Fortress (Festung Hohensalzburg), overlooking the Old Town, is one of the largest castles in Europe

- Mirabell Palace, with its wide gardens

- Salzburg Residenz, the magnificent former residence of the Prince-Archbishops

- Residenzgalerie, an art museum in the Salzburg Residenz

- Residenzplatz

- Großes Festspielhaus

- House for Mozart

- Mozart's birthplace

- Getreidegasse

- St. Sebastian's Church

- Sphaera (Salzburg), a sculpture of a man on a golden sphere (Stephan Balkenhol, 2007)

Outside the Old Town

- Schloss Leopoldskron, a rococo palace and national historic monument in Leopoldskron-Moos, a southern district of Salzburg

- Hellbrunn with its parks and castles

- The Sound of Music tour companies who operate tours of film locations

- Hangar-7, a multifunctional building owned by Red Bull, with a collection of historical airplanes, helicopters and Formula One racing cars

Greater Salzburg area

- Anif Castle, located south of the city in Anif

- Shrine of Our Lady of Maria Plain, a late Baroque church on the northern edge of Salzburg

- Salzburger Freilichtmuseum Großgmain, an open-air museum containing old farmhouses from all over the state assembled in an historic setting

- Schloss Klessheim, a palace and casino, formerly used by Adolf Hitler

- Berghof, Hitler's mountain retreat near Berchtesgaden

- Kehlsteinhaus, the only remnant of Hitler's Berghof

- Salzkammergut, an area of lakes east of the city

- Untersberg mountain, next to the city on the Austria–Germany border, with panoramic views of Salzburg and the surrounding Alps

- Skiing is an attraction during winter. Salzburg itself has no skiing facilities, but it acts as a gateway to skiing areas to the south. During the winter months its airport receives charter flights from around Europe.

- Salzburg Zoo, located south of the city in Anif

Education

Salzburg is a centre of education and home to three universities, as well as several professional colleges and gymnasiums (high schools).

Universities and higher education institutions

- Salzburg University of Applied Sciences[32]

- University of Salzburg, a federal public university

- Paracelsus Medical University

- Mozarteum University Salzburg, a public music and dramatic arts university

- Alma Mater Europaea, a private university

- SEAD – Salzburg Experimental Academy of Dance

Notable citizens

- Saint Liutberga (died c. 870).

- The composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, born and raised in Salzburg when it was part of the Prince-Archbishopric of Salzburg within the Holy Roman Empire, was employed as musician at the archbishopal court from 1773 to 1781. His house of birth and residence are tourist attractions. His family is buried in a small church graveyard in the old town, and there are many monuments to "Wolferl" in the city.

- The composer Johann Michael Haydn, brother of the composer Joseph Haydn. His works were admired by Mozart and Schubert. He was also the teacher of Carl Maria von Weber and Anton Diabelli and is known for his sacred music.

- Christian Doppler, expert on acoustic theory, was born in Salzburg. He is most known for his discovery of the Doppler effect.

- Josef Mohr, born in Salzburg. Together with Franz Gruber, he composed and wrote the text for "Silent Night". As a priest in neighbouring Oberndorf he performed the song for the first time on Christmas Eve 1818.[33]

- King Otto of Greece was born Prince Otto Friedrich Ludwig of Bavaria at the Palace of Mirabell, a few days before the city reverted from Bavarian to Austrian rule.

- Writer Stefan Zweig, lived in Salzburg for about 15 years, until 1934.

- Maria von Trapp (later Maria Trapp) and her family lived in Salzburg until they fled to the United States following the Nazi takeover.

- Salzburg is the birthplace of Hans Makart, a 19th-century Austrian painter-decorator and national celebrity. Makartplatz (Makart Square) is named in his honour.

- Writer Thomas Bernhard, raised in Salzburg and spent part of his life there.

- Herbert von Karajan, notable orchestral conductor. He was born in Salzburg and died in 1989 in neighbouring Anif.

- Roland Ratzenberger, Formula One driver, was born in Salzburg. He died in practice for the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix.

- Joseph Leutgeb, virtuoso on the French horn, was part of the archbishop's court.

- Paracelsus, Swiss physician, alchemist and astrologer of the German Renaissance, died in Salzburg.

- Klaus Ager, distinguished contemporary composer and Mozarteum professor, was born in Salzburg on 10 May 1946.

- Alex Jesaulenko, former Australian rules footballer for Carlton and Australian Football Hall of Fame member with "Legend" status was born in Salzburg on 2 August 1945.

- Georg Trakl, one of the most important voices in German literature was born in Salzburg.

- Theodor Herzl, worked in the courts in Salzburg during the year after he earned his law degree in 1884.[34]

- Skydiver and BASE Jumper Felix Baumgartner, who set three world records during the Red Bull Stratos project on 14 October 2012.

- Hilda Crozzoli, Austria's first female architect and civil engineer.

Events

- The Salzburg Festival is a famous music and theatre festival that attracts visitors during the months of July and August each year. A smaller Salzburg Easter Festival is held around Easter each year.

- The Europrix multimedia award takes place in Salzburg.

- Electric Love Festival takes place in Salzburg

Transport

Salzburg Hauptbahnhof is served by comprehensive rail connections, with frequent east–west trains serving Vienna, Munich, Innsbruck, and Zürich, including daily high-speed ICE services. The city acts as a hub for south-bound trains through the Alps into Italy.

Salzburg Airport has scheduled flights to European cities such as Frankfurt, Vienna, London, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Brussels, Düsseldorf, and Zürich, as well as Hamburg, Edinburgh and Dublin. In addition to these, there are numerous charter flights.

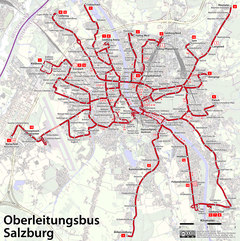

In the main city, there is the Salzburg trolleybus system and bus system with a total of more than 20 lines, and service every 10 minutes. Salzburg has an S-Bahn system with four Lines (S1, S2, S3, S11), trains depart from the main station every 30 minutes, and they are part of the ÖBB network. Suburb line number S1 reaches the world-famous Silent Night chapel in Oberndorf in about 25 minutes.

Popular culture

In the 1960s, the movie The Sound of Music used some locations in and around Salzburg and the state of Salzburg. The movie was based on the true story of Maria von Trapp, who took up with an aristocratic family and fled the German Anschluss. The town draws many visitors who wish to visit the filming locations, alone or on tours.

The city briefly appears on the map when Indiana Jones travels through the city in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Salzburg is the setting for the Austrian crime series Stockinger.

In the 2010 film Knight & Day, Salzburg serves as the backdrop for a large portion of the film.

The 2017 novel 'A Rock 'n' Roll Lovestyle' by Kiltie Jackson is set predominately in Salzburg and surrounding areas.

Language

Austrian German is widely written and differs from Germany's standard variation only in some vocabulary and a few grammar points. Salzburg belongs to the region of Austro-Bavarian dialects, in particular Central Bavarian.[35] It is widely spoken by young and old alike although professors of linguistics from the Universität Salzburg, Irmgard Kaiser and Hannes Scheutz, have seen over the past few years a reduction in the number of dialect speakers in the city.[36][37] Although more and more school children are speaking standard German, Scheutz feels it has less to do with parental influence and more to do with media consumption.[38]

Sports

Football

The former SV Austria Salzburg reached the UEFA Cup final in 1994. On 6 April 2005 Red Bull bought the club and changed its name into FC Red Bull Salzburg. The home stadium of Red Bull Salzburg is the Wals Siezenheim Stadium in a suburb in the agglomeration of Salzburg and was one of the venues for the 2008 European Football Championship. The FC Red Bull Salzburg plays in the Austrian Bundesliga.

After Red Bull had bought the SV Austria Salzburg and changed its name and team colors, some supporters of the club decided to leave and form a new club with the old name and old colors, wanting to preserve the traditions of their club. The reformed SV Austria Salzburg was founded in 2005 and currently plays in the Erste Liga, only one tier below the Bundesliga.

Ice hockey

Red Bull also sponsors the local ice hockey team, the EC Salzburg Red Bulls. The team plays in the Erste Bank Eishockey Liga, an Austria-headquartered crossborder league featuring the best teams from Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia and Italy, as well as one Czech team.

Other sports

Salzburg was a candidate city for the 2010 and 2014 Winter Olympics, but lost to Vancouver and Sochi respectively.

International relations

Twin towns—sister cities

Salzburg is twinned with:[39]

Gallery

- Mozart's birthplace at Getreidegasse 9

_-_Mirabellgarten.jpg) View from Mirabellgarten at night

View from Mirabellgarten at night- The famous fountain in Mirabell Gardens (seen in the "Do-Re-Mi" song from The Sound of Music)

The Sunset at the Staatsbrücke

The Sunset at the Staatsbrücke Sigmund Haffner Gasse – Rathaus

Sigmund Haffner Gasse – Rathaus Residential and studio house Lechner in the old town

Residential and studio house Lechner in the old town- The Salzburg basin

- The fortress (background), Salzburg Cathedral (middle), the Salzach (foreground)

- ÖBB rail connection to Salzburg in Innsbruck

- Mozart monument

Fountain in the Residenzplatz

Fountain in the Residenzplatz- Palace of Mirabell.

- View of the old town and fortress, seen from Kapuzinerberg

_cropped.jpg) Salzburg at ight

Salzburg at ight

Notes

References

- "Dauersiedlungsraum der Gemeinden Politischen Bezirke und Bundesländer - Gebietsstand 1.1.2018". Statistics Austria. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Salzburg in Zahlen". Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- "Salzburg". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Salzburg". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Salzburg". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Salzburg". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- "Österreich - Größte Städte 2019". Statista (in German). Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Why Salzburg is Austria's most inspiring city". www.thelocal.at. 2016-11-21. Retrieved 2019-10-15.

- de Fabianis, Valeria, ed. Castles of the World. Metro Books, 2013, p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4351-4845-1

- de Fabianis, p. 167.

- de Fabianis, p. 167

- Visit Salzburg, Salzburg's History: Coming a Long Way.

- Frank L. Perry Jr., Catholics Cleanse Salzburg of Protestants Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, The Georgia Salzburger Society.

- Times Atlas of European History, 3rd Ed., 2002

- de Fabianis, Valeria, ed. Castles of the World. Metro Books, 2013, p. 168. ISBN 978-1-4351-4845-1

- "AEIOU Österreich-Lexikon – Konzentrationslager, KZ". Austria-Forum.org. Retrieved 2013-06-24.

- E.B. (26 September 2017). "The Salzburg Festival is a boon to the local economy". The Economist.

- "Klimamittel 1981–2010: Lufttemperatur" (in German). Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Klimamittel 1981–2010: Niederschlag" (in German). Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Klimamittel 1981–2010: Schnee" (in German). Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Klimamittel 1981–2010: Luftfeuchtigkeit" (in German). Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Klimamittel 1981–2010: Strahlung" (in German). Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics. Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Station Salzburg" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Klimadaten von Österreich 1971–2000 – Salzburg-Salzburg–Flughafen" (in German). Central Institute for Meteorology and Geodynamics. Archived from the original on 12 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "Bevölkerung zu Jahres-/Quartalsanfang". Statistik.at. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Statistisches Jahrbuch der Landeshauptstadt Salzburg" (PDF). Stadt Salzburg. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- "Architecture : Salzburg Sights by Period". Visit-salzburg.net. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Archived May 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Preisträger Salzburg". Archived from the original on June 30, 2013.

- "flow – der VERBUND Blog". Verbund.com. 2012-10-15. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "Red Bull′s Hangar-7 at Salzburg Airport". Visit Salzburg. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- "fh-salzburg". Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Joseph Mohr (1792–1848) Priest and author of Silent Night". www.stillenacht.com. Retrieved 2018-06-07.

- "Theodor Herzl (1860–1904)". Jewish Agency for Israel. Archived from the original on September 30, 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-08.

He received a doctorate in law in 1884 and worked for a short while in courts in Vienna and Salzburg.

- Klaaß, Daniel (2009). Untersuchungen zu ausgewählten Aspekten des Konsonantismus bei österreichischen Nachrichtensprechern. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. p. 38. ISBN 9783631585399. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Reitmeier, Simone. "Salzburg Mundart: Stirbt der Dialekt in naher Zukunft aus?". weekend.at. Weekend Online GmbH. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Winkler, Jacqueline. "Dialekte in ihrer heutigen Form sterben aus". salzburg24. Salzburg Digital GmbH. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Pumhösel, Alois. "Germanist: "Kinder vor Dialekt bewahren zu wollen ist absurd"". Der Standard. STANDARD Verlagsgesellschaft m.b.H. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- "Salzburger Städtepartnerschaften" (in German). Stadt Salzburg. Retrieved 2015-05-29.

- "Dresden — Partner Cities". © 2008 Landeshauptstadt Dresden. Archived from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-29.

Bibliography

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salzburg (Stadt). |

- Visit-Salzburg.net

- Salzburg Tourist Office – Salzburg city tourist board website