District (Austria)

In Austrian politics, a district (German: Bezirk) is a second-level division of the executive arm of the country's government. District offices are the primary point of contact between resident and state for most acts of government that exceed municipal purview: marriage licenses, driver licenses, passports, assembly permits, hunting permits, or dealings with public health officers for example all involve interaction with the district administrative authority (Bezirksverwaltungsbehörde).

Austrian constitutional law distinguishes two types of district administrative authority:

- district commissions (Bezirkshauptmannschaften), district administrative authorities that exist as stand-alone bureaus;

- statutory cities (Städte mit eigenem Statut or Statutarstädte), cities that have been vested with district administration functions in addition to their municipal responsibilities, i.e. district administrative authorities that only exist as a secondary role filled by something that primarily is a city (marked in the table with an asterisk (*).

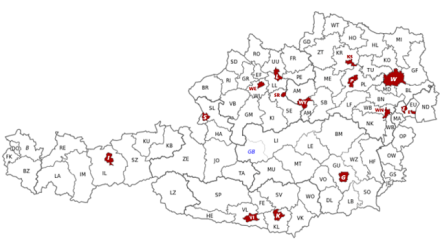

As of 2017, there are 94 districts, of which 79 are districts headed by district commissions and 15 are statutory cities. Many districts are geographically congruent with one of the country's 114 judicial venues.

Statutory cities are not usually referred to as "districts" outside government publications and the legal literature. For brevity, government agencies will sometimes use the term "rural districts" (Landbezirke) for districts headed by district commissions, although the expression does not appear in any law and many "rural districts" are not very rural.

District commissions

A district headed by a district commission typically covers somewhere between ten and thirty municipalities. As a purely administrative unit, a district does not hold elections and therefore does not choose its own officials. The district governor (Bezirkshauptmann) is appointed by the provincial governor; the district civil servants are province employees.

In the provincial laws of Lower Austria and Vorarlberg, districts headed by district commissions are called administrative districts (Verwaltungsbezirke). In Burgenland, Carinthia, Salzburg, Styria, Upper Austria, and Tyrol, the term used is political district (politischer Bezirk). National law, including national constitutional law, uses all three variants interchangeably. [note 1]

Statutory cities

A statutory city is a city vested with both municipal and district administrative responsibility.[4] Town hall personnel also serves as district personnel; the mayor also discharges the powers and duties of a head of district commission. City management thus functions both as a regional government and a branch of the national government at the same time.

Most of the 15 statutory cities are major regional population centers with residents numbering in the tens of thousands. The smallest statutory city is barely more than a village, but owes its status to a quirk of history: Rust, Burgenland, current population 1900 (2017), has enjoyed special autonomy since it was made a royal free city by the Kingdom of Hungary in 1681; its privilege was grandfathered into the district system when Hungary ceded the region (later called Burgenland) to Austria in 1921.

The constitution stipulates that a community with at least 20,000 residents can demand to be elevated to statutory city status by its respective province, unless the province can demonstrate this would jeopardize regional interests, or unless the national government objects. The last community to have invoked this right is Wels, a statutory city since 1964. As of 2014, ten other communities are eligible but not interested.

The statutory city of Vienna, a community with well over 1.8 million residents, is divided into 23 municipal districts (Gemeindebezirke). Despite the similar name and the comparable role they fill, municipal districts have a different legal basis than districts. The statutory cities of Graz and Klagenfurt also have subdivisions referred to as "municipal districts," but these are merely neighborhood-size divisions of the city administration.[5][6]

Naming quirks

Austria strictly speaking does not name districts but district administrative authorities. The German term for "district commission" and "city," Bezirkshauptmannschaft and Stadt, respectively, is part of the official proper name of each such entity. This means that there can be pairs of districts whose two proper names contain the same toponym. Several such pairs do in fact exist. There are, for example, two district administrative authorities sharing the toponym Innsbruck: the (statutory) city of Innsbruck and the Innsbruck district commission.

To avoid confusion, the names of the rural districts in these pairs are commonly rendered with the suffix -Land, in this context roughly meaning "region." The customary name for the city of Innsbruck is Innsbruck, the customary name for the district headed by the Innsbruck district commission is Innsbruck-Land. While this usage is nearly universal both in the media and in everyday spoken German and even appears in the occasional government publication, the suffix -Land is not part of any official, legal designation.

History

Austrian Empire

From the middle ages until the mid-eighteenth century, the Austrian Empire was an absolute monarchy with no written constitution and no modern concept of the rule of law. [7] [8] Provinces were ruled by the monarch, usually the emperor himself or a vassal of the emperor, supported by their personal advisors and the estates of the realm. The precise nature of the relationship between ruler and estates was different from region to region. Regional administrators were appointed by the monarch and answerable to the monarch. The first step towards modern bureaucracy was taken by Empress Maria Theresa, who in 1753 imposed an empire-wide system of district offices (Kreisämter). A major break with tradition, the system was unpopular at first; "in some provinces considerable resistance had to be overcome." The district offices never became fully operational in the Kingdom of Hungary.[9]

Following the first wave of the revolutions of 1848, Emperor Ferdinand I and his minister of the interior, Franz Xaver von Pillersdorf, enacted Austria's first formal constitution. The constitution completely abolished the estates and called for a separation of executive and judicial authority, immediately crippling most existing regional institutions and leaving district offices as the backbone of the empire's administration. Ferdinand having been forced to abdicate by a second wave of revolutions, his successor Franz Joseph I swiftly went to work transforming Austria from a constitutional monarchy back into an absolute one but kept relying on district offices at first. In fact, he strengthened the system. His March Constitution retained the separation of judiciary and executive. It prescribed a partition of the empire into judicial venues, with courts to be headed by professional judges, and a separate partition into administrative districts, to be headed by professional civil servants. An 1849 Imperial Resolution fleshed out the details.[1] The districts started functioning in 1850, many of them already in their present-day borders.

The March Constitution was never fully implemented and formally scrapped in 1851.[10] Officially returning to full autocracy, the Emperor abolished the separation of powers. Administrative districts were merged with judicial venues; district administrative authorities with district courts. [11] Intellectuals aside, few objections were raised. The bulk of the population was still living and working on manorial lands and was still used to the lord of the manor being head of some form of manorial court.

Cisleithania

Following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, Franz Joseph was forced to assent to the December Constitution, a set of five of Basic Laws that restored constitutional monarchy in Cisleithania. One of these Basic Laws, in particular, restored the separation of judiciary and executive.[12] Pursuant to this stipulation, the merger of administrative and judicial districts was reversed the following year;[2] the law in question established the districts in essentially their modern form. No attempt was made this time to impose the scheme on Hungary. The Kingdom of Hungary was now a separate country, fully independent in every respect save defense and international relations, and neither needed nor wanted to copy civil administration policies enacted in Vienna.

No significant changes were made between the 1868 restoration and the 1918 collapse of the Habsburg monarchy. Vienna was growing significantly during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, absorbing dozens of suburbs. Three districts disappeared between 1891 and 1918 due to their domains being incorporated into the imperial capital wholesale. Two other districts lost parts of their territories to Vienna. Eleven new districts were carved out of existing districts between 1891 and 1918 due to general population growth.

First Republic

Following the collapse of the monarchy, the 1920 constitution of the First Austrian Republic retained the district system.[13] At least one of the principal framers, Karl Renner, had suggested to endow districts with county-like elected councils and some degree of legislative authority, but could not gain consensus for this idea.

The 1920 constitution characterizes Austria as a federal republic and its provinces as quasi-sovereign federated states. A 1925 constitutional reform, a broad revision of general devolutionary tendency, transformed districts from divisions of the national executive into divisions of the new "state" executives.[14][15] The replanting had virtually no practical consequences; enforcing national law and handling applications to the national government remain every district's main activities. Province governments have the authority to redraw district boundaries but can neither create nor dissolve districts, nor change how they work, without the assent of the cabinet.[16]

In 1921, Hungary ceded Burgenland to Austria. While part of the Kingdom of Hungary, the rural border region had been partitioned into seven wards (Oberstuhlrichterämter), clusters of small towns and villages headed by a magistrate who served as both the district judge and the supervisor of the local administrators. Austria simply transformed the seven wards into seven new districts. The region also included two royal free cities, Eisenstadt and Rust; these were made into statutory cities, thus also becoming districts.

Land Österreich

With the March 1938 annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany, Austria initially became a state (Land) of the German Reich. In May, Vienna was expanded to create Greater Vienna (Groß-Wien), absorbing another four districts. Two weakly populated rural districts were discontinued as well. In October, Burgenland was dissolved, its northern half being attached to Lower Austria and its southern half to Styria. [17]

Between May 1939 and March 1940, Austria was dissolved. Its eight remaining provinces became seven Reichsgaue, answerable not to Vienna but directly to Berlin. Several statutory cities lost their special status and were incorporated into the respectively adjacent rural districts; the city of Krems on the other hand was promoted to district status. The districts otherwise remained intact, but they were now German Kreise instead of Austrian Bezirke.

Second Republic

Reborn with the downfall of Nazi Germany in 1945, the Republic of Austria immediately restored the administrative structure torn down between 1938 and 1940, putting the districts back in place. The only exception were the districts that had been absorbed into Vienna.

Austria had been divided into four occupation zones and jointly occupied by the United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, and France. Lower Austria, the region surrounding Vienna, was part of the Soviet zone. The capital itself was considered too valuable to be left to any one power and was, just like Berlin, separately divided into four sectors. In drafting their plans, the allies worked from the city's pre-1938 borders. The Nazi expansion of Vienna, however, had made some sense. A number of rural areas incorporated into Greater Vienna were inimical. Most of Lower Austria had been leaning conservative to nationalist for a century; Vienna had been a bastion of Social Democracy for decades. The bureaucracy steering Vienna, a city of industry and finance, was sociologically distant from the agricultural countryside. Some of the suburbs affected, however, had long had much closer ties to the capital than to the rest of their former province, both socially and in terms of infrastructure. Permanently ejecting these suburbs from Vienna would have been inadvisable. Reaffirming the Nazi border changes either entirely or in part, on the other hand, would have led to demarcation discrepancies between Austrian and allied administrative divisions. Disputes regarding communal debt added to the problem.

Hotly contested between the Social Democrats dominating Vienna and the People's Party ruling Lower Austria, the question was not resolved until 1954. One of the traditional districts annexed by the city in 1938 was restored. Parts of several other traditional districts annexed were united to form a second new district.

In 1964, the city of Wels was elevated to statutory city status.

Two other new districts were established in 1969 and 1982, respectively.

Effective January 1, 2012, Styria merged the districts of Judenburg and Knittelfeld to form the Murtal district. The merger was part of program aimed at streamlining the regional bureaucracy. On January 1, 2013, three more mergers followed: Bruck was merged with Mürzzuschlag, Hartberg with Fürstenfeld, and Feldbach with Radkersburg.[18] Effective January 1, 2017, Lower Austria split the districts of Wien-Umgebung into parts which were merged with the districts of Bruck an der Leitha, Korneuburg, Sankt Pölten and Tulln.

List of current districts

The suffixes -Land and Umgebung is not part of the official name of any of the districts using it. In cases where a statutory city and a rural district share the same toponym, the rural district has -Land or Umgebung attached to its name as a matter of customary usage to avoid ambiguity (officially not in Lower Austria). All 13 of these rural districts have their administrative centers located in the respective statutory cities, thus outside of the districts themselves.

| Code | District | Established | License plate | Administrative seat | Population 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | Eisenstadt * | 1921 | E | – | 13,485 |

| 102 | Rust * | 1921 | E[note 2] | – | 1,942 |

| 103 | Eisenstadt-Umgebung | 1921 | EU | Eisenstadt (not part of the district) | 41,474 |

| 104 | Güssing | 1921 | GS | Güssing | 26,394 |

| 105 | Jennersdorf | 1921 | JE | Jennersdorf | 17,376 |

| 106 | Mattersburg | 1921 | MA | Mattersburg | 39,134 |

| 107 | Neusiedl am See | 1921 | ND | Neusiedl am See | 56,504 |

| 108 | Oberpullendorf | 1921 | OP | Oberpullendorf | 37,534 |

| 109 | Oberwart | 1921 | OW | Oberwart | 53,573 |

| 201 | Klagenfurt * | 1850 | K | – | 96,640 |

| 202 | Villach * | 1932 | VI | – | 60,004 |

| 203 | Hermagor | 1868 | HE | Hermagor-Pressegger See | 18,547 |

| 204 | Klagenfurt-Land | 1868 | KL | Klagenfurt (not part of the district) | 58,435 |

| 205 | Sankt Veit an der Glan | 1868 | SV | Sankt Veit an der Glan | 55,394 |

| 206 | Spittal an der Drau | 1868 | SP | Spittal an der Drau | 76,971 |

| 207 | Villach-Land | 1868 | VL | Villach (not part of the district) | 64,268 |

| 208 | Völkermarkt | 1868 | VK | Völkermarkt | 42,068 |

| 209 | Wolfsberg | 1868 | WO | Wolfsberg | 53,472 |

| 210 | Feldkirchen | 1982 | FE | Feldkirchen in Kärnten | 30,082 |

| 301 | Krems an der Donau * | 1938 | KS | – | 24,085 |

| 302 | Sankt Pölten * | 1922 | P | – | 52,145 |

| 303 | Waidhofen an der Ybbs * | 1868 | WY | – | 11,341 |

| 304 | Wiener Neustadt * | 1866 | WN | – | 42,273 |

| 305 | Amstetten | 1868 | AM | Amstetten | 112,944 |

| 306 | Baden | 1868 | BN | Baden | 140,078 |

| 307 | Bruck an der Leitha | 1868 | BL, SW[note 3] | Bruck an der Leitha | 43,615 |

| 308 | Gänserndorf | 1901 | GF | Gänserndorf | 97,460 |

| 309 | Gmünd | 1899 | GD | Gmünd | 37,420 |

| 310 | Hollabrunn | 1868 | HL | Hollabrunn | 50,065 |

| 311 | Horn | 1868 | HO | Horn | 31,273 |

| 312 | Korneuburg | 1868 | KO | Korneuburg | 73,370 |

| 313 | Krems | 1868 | KR | Krems an der Donau (not part of the district) | 55,945 |

| 314 | Lilienfeld[note 4] | 1868 | LF | Lilienfeld | 26,040 |

| 315 | Melk | 1896 | ME | Melk | 76,369 |

| 316 | Mistelbach | 1868 | MI | Mistelbach | 74,150 |

| 317 | Mödling | 1897 | MD | Mödling | 115,677 |

| 318 | Neunkirchen | 1868 | NK | Neunkirchen | 85,539 |

| 319 | Sankt Pölten | 1868 | PL | Sankt Pölten (not part of the district) | 97,365 |

| 320 | Scheibbs | 1868 | SB | Scheibbs | 41,073 |

| 321 | Tulln | 1892 | TU | Tulln | 72,104 |

| 322 | Waidhofen an der Thaya | 1868 | WT | Waidhofen an der Thaya | 26,424 |

| 323 | Wiener Neustadt | 1868 | WB | Wiener Neustadt (not part of the district) | 75,285 |

| 325 | Zwettl | 1868 | ZT | Zwettl | 43,102 |

| 401 | Linz * | 1866 | L | – | 183,814 |

| 402 | Steyr * | 1867 | SR | – | 38,120 |

| 403 | Wels * | 1964 | WE | – | 59,339 |

| 404 | Braunau am Inn | 1868 | BR | Braunau am Inn | 98,842 |

| 405 | Eferding | 1907 | EF | Eferding | 31,961 |

| 406 | Freistadt | 1868 | FR | Freistadt | 65,208 |

| 407 | Gmunden | 1868 | GM | Gmunden | 99,540 |

| 408 | Grieskirchen | 1911 | GR | Grieskirchen | 62,938 |

| 409 | Kirchdorf an der Krems | 1868 | KI | Kirchdorf an der Krems | 55,571 |

| 410 | Linz-Land | 1868 | LL | Linz (not part of the district) | 141,540 |

| 411 | Perg | 1868 | PE | Perg | 66,269 |

| 412 | Ried im Innkreis | 1868 | RI | Ried im Innkreis | 58,714 |

| 413 | Rohrbach | 1868 | RO | Rohrbach-Berg | 56,455 |

| 414 | Schärding | 1868 | SD | Schärding | 56,287 |

| 415 | Steyr-Land | 1868 | SE | Steyr (not part of the district) | 58,618 |

| 416 | Urfahr-Umgebung | 1919 | UU | Linz (not part of the district) | 82,109 |

| 417 | Vöcklabruck | 1868 | VB | Vöcklabruck | 131,497 |

| 418 | Wels-Land | 1868 | WL | Wels (not part of the district) | 68,600 |

| 501 | Salzburg * | 1869 | S | – | 146,631 |

| 502 | Hallein | 1896 | HA | Hallein | 58,336 |

| 503 | Salzburg-Umgebung | 1868 | SL | Salzburg (not part of the district) | 145,275 |

| 504 | Sankt Johann im Pongau | 1868 | JO | Sankt Johann im Pongau | 78,614 |

| 505 | Tamsweg | 1868 | TA | Tamsweg | 20,450 |

| 506 | Zell am See | 1868 | ZE | Zell am See | 84,964 |

| 601 | Graz * | 1850 | G | – | 269,997 |

| 603 | Deutschlandsberg | 1868 | DL | Deutschlandsberg | 60,466 |

| 606 | Graz-Umgebung | 1868 | GU | Graz (not part of the district) | 145,660 |

| 610 | Leibnitz | 1868 | LB | Leibnitz | 77,774 |

| 611 | Leoben | 1868 | LE, LN[note 5] | Leoben | 61,771 |

| 612 | Liezen | 1868 | GB, LI[note 6] | Liezen | 78,893 |

| 614 | Murau | 1868 | MU | Murau | 28,740 |

| 616 | Voitsberg | 1891 | VO | Voitsberg | 51,559 |

| 617 | Weiz | 1868 | WZ | Weiz | 88,355 |

| 620 | Murtal | 2012 | MT | Judenburg | 73,041 |

| 621 | Bruck-Mürzzuschlag | 2013 | BM | Bruck an der Mur | 100,855 |

| 622 | Hartberg-Fürstenfeld | 2013 | HF | Hartberg | 89,252 |

| 623 | Südoststeiermark | 2013 | SO | Feldbach | 88,843 |

| 701 | Innsbruck * | 1850 | I | – | 124,579 |

| 702 | Imst | 1868 | IM | Imst | 57,271 |

| 703 | Innsbruck-Land | 1868 | IL | Innsbruck (not part of the district) | 169,680 |

| 704 | Kitzbühel | 1868 | KB | Kitzbühel | 62,318 |

| 705 | Kufstein | 1868 | KU | Kufstein | 103,317 |

| 706 | Landeck | 1868 | LA | Landeck | 43,906 |

| 707 | Lienz | 1868 | LZ | Lienz | 48,990 |

| 708 | Reutte | 1868 | RE | Reutte | 31,672 |

| 709 | Schwaz | 1868 | SZ | Schwaz | 80,305 |

| 801 | Bludenz | 1868 | BZ | Bludenz | 61,100 |

| 802 | Bregenz | 1868 | B | Bregenz | 128,568 |

| 803 | Dornbirn | 1969 | DO | Dornbirn | 84,117 |

| 804 | Feldkirch | 1868 | FK | Feldkirch | 101,497 |

| – | Wien * | 1850 | W | – | 1,766,746 |

Historical districts

This section only lists districts covering regions that are still part of present-day Austria. Districts lost following the dissolution of Cisleithania in 1918 are omitted.

| Code | District | Years | License plate | Administrative seat | Population 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | Floridsdorf | 1897–1905 | – | Floridsdorf | |

| – | Floridsdorf Umgebung | 1906–1938 | – | Floridsdorf | |

| – | Gröbming | 1868–1938 | – | Gröbming | |

| – | Groß-Enzersdorf | 1868–1896 | – | Groß-Enzersdorf | |

| – | Hernals | 1868–1891 | – | Hernals | |

| – | Hietzing | 1868–1891 | – | Hietzing | |

| – | Hietzing Umgebung | 1892–1938 | – | Hietzing | |

| – | Pöggstall | 1899–1938 | – | Pöggstall | |

| – | Sechshaus | 1868–1891 | – | Sechshaus | |

| – | Urfahr | 1903–1919 | – | Urfahr | |

| – | Währing | 1868–1892 | – | Währing | |

| 324 | Wien-Umgebung | 1954–2016 | WU, SW[note 7] | Klosterneuburg | 117,343 |

| 602 | Bruck an der Mur | 1868–2012 | BM | Bruck an der Mur | 62,000 |

| 604 | Feldbach | 1868–2012 | FB | Feldbach, Styria | 67,046 |

| 605 | Fürstenfeld | 1938–2012 | FF | Fürstenfeld | 23,000 |

| 607 | Hartberg | 1868–2012 | HB | Hartberg | 66,000 |

| 608 | Judenburg | 1868–2011 | JU | Judenburg | 44,983 |

| 609 | Knittelfeld | 1946–2011 | KF | Knittelfeld | 29,095 |

| 613 | Mürzzuschlag | 1903–2012 | MZ | Mürzzuschlag | 40,207 |

| 615 | Radkersburg | 1868–2012 | RA | Radkersburg | 22,911 |

Notes

- The 1849 Imperial Resolution creating the district system calls districts just that, "districts."[1] The 1868 Act establishing districts in their modern form adds the terms "administrative district" (Amtsbezirk) and "political administrative district" (politischer Amtsbezirk).[2] The 1920 Federal Constitutional Law prefers "district" but occasionally uses "political district" to emphasize is it not referring to jucidial districts. Over the course of the dozens of revisions the Law has undergone since 1920, all occurrences of either were excised; the version currently in force still mentions district administrative authorities but no longer mentions districts. The 1955 Austrian State Treaty contains a reference to the "administrative districts" of Carinthia, Burgenland, and Styria, even though local legal documents would have called them "political districts."[3]

- Rust shares Eisenstadt's E code.

- SW for the city of Schwechat, BL for the rest of the district.

- Lilienfeld was established in 1868, dissolved in 1890, and restored in 1897. From 1933 to 1938 Lilienfeld was a branch office of St. Pölten, from 1938 to 1945 a German Kreis, and from 1945 to 1952 a branch office of St. Pölten again. In 1953 it was restored to full district status once more.

- LE for the city of Leoben, LN for the rest of the district.

- GB for subdistrict (Expositur) Gröbming; LI elsewhere.

- SW for the city of Schwechat, WU for the rest of the district.

References

- Kaiserliche Entschließung vom 26. Juni 1849, wodurch die Grundzüge für die Organisation der politischen Verwaltungs-Behörden genehmiget werden; RGBl. 295/1849

- Gesetz von 19. Mai 1868, über die Einrichtung der politischen Verwaltungsbehörden; RGBl. 44/1868

- Staatsvertrag, betreffend die Wiederherstellung eines unabhängigen und demokratischen Österreich; BGBl. 152/1955

- Federal Constitutional Law article 116; BGBl. 1/1930; last amended in BGBl. 100/2003

- "Die 17 Bezirke". Stadt Graz. 2014. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- "Registerzählung vom 31 October 2011, Bevölkerung nach Ortschaften" (PDF). Statistik Austria. 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- Hoke, Rudolf (1996) [1992]. Österreichische und deutsche Rechtsgeschichte (in German) (2nd ed.). ISBN 3-205-98179-0.

- Brauneder, Wilhelm (2009) [1979]. Österreichische Verfassungsgeschichte (in German) (11th ed.). ISBN 978-3-214-14876-8.

- Lechleitner, Thomas (1997). "Die Bezirkshauptmannschaft". Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- Kaiserliches Patent vom 31. Dezember 1851; RGBl. 3/1851

- Gesetz vom 19. Jänner 1853, RGBl. 10/1853

- Staatsgrundgesetz vom 21. Dezember 1867, über die richterliche Gewalt; RGBl. 144/1867

- Gesetz vom 1. Oktober 1920, womit die Republik Österreich als Bundesstaat eingerichtet wird (Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz); SGBl. 450/1920

- Verordnung des Bundeskanzlers vom 26. September 1925, betreffende die Wiederverlautbarung des Übergangsgesetzes; BGBl. 368/1925

- "Bezirkshauptmannschaft (english)". Austria-Forum. March 27, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- Federal Constitutional Law article 15; BGBl. 1/1930; last amended in BGBl. 100/2003.

- Gesetz über Gebietsveränderungen im Lande Österreich vom 1. Oktober 1938; GBLÖ 443/1938

- "Maßnahmen der Verwaltungsreform". Land Steiermark. 2010. Retrieved November 28, 2014.