Iroquois

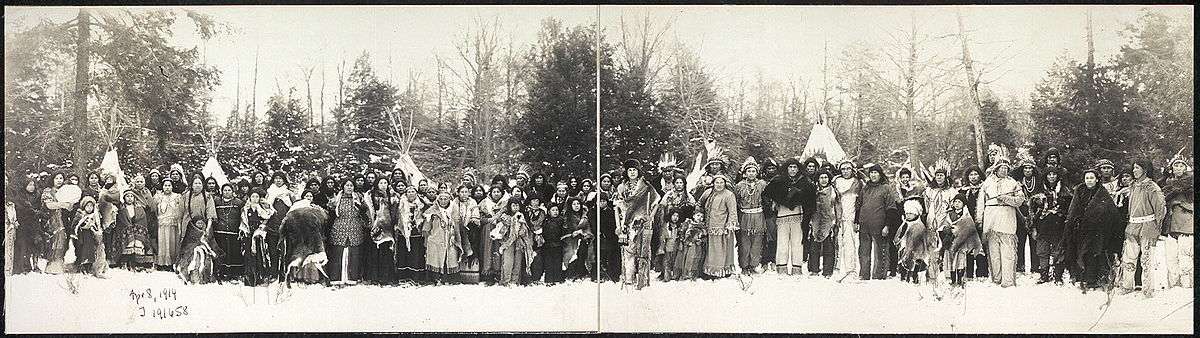

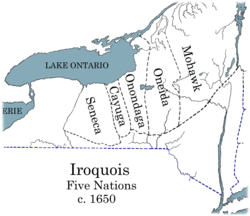

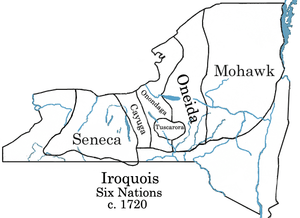

The Iroquois (/ˈɪrəkwɔɪ/ or /ˈɪrəkwɑː/) or Haudenosaunee (/ˈhoʊdənoʊˈʃoʊni/;[1] "People of the Longhouse") are a historically powerful northeast Native American confederacy in North America. They were known during the colonial years to the French as the Iroquois League, and later as the Iroquois Confederacy, and to the English as the Five Nations, comprising the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca. After 1722, they accepted the Tuscarora people from the Southeast into their confederacy, as they were also Iroquoian-speaking, and became known as the Six Nations.

Iroquois Confederacy Haudenosaunee | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Map showing historical (in purple) and currently recognized (in pink) Iroquois territory claims. | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Recognized confederate state, later became an unrecognized state | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Iroquoian languages | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Confederation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Grand Council of the Six Nations | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | Between 1450 and 1660 (estimate) | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1867- (slow removals of sovereignty) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

The Iroquois have absorbed many other individuals from various peoples into their tribes as a result of warfare, adoption of captives, and by offering shelter to displaced peoples. Culturally, all are considered members of the clans and tribes into which they are adopted by families.

The historic St. Lawrence Iroquoians, Wyandot (Huron), Erie, and Susquehannock, all independent peoples, also spoke Iroquoian languages. In the larger sense of linguistic families, they are often considered Iroquoian peoples because of their similar languages and cultures, all descended from the Proto-Iroquoian people and language; politically, however, they were traditional enemies of the Iroquois League.[2] In addition, Cherokee is an Iroquoian language: the Cherokee people are believed to have migrated south from the Great Lakes in ancient times, settling in the backcountry of the Southeast United States, including what is now Tennessee.

In 2010, more than 45,000 enrolled Six Nations people lived in Canada, and about 80,000 in the United States.

Names

The most common name for the confederacy, Iroquois, is of somewhat obscure origin. The first time it appears in writing is in the account of Samuel de Champlain of his journey to Tadoussac in 1603, where it occurs as "Irocois".[3] Other spellings appearing in the earliest sources include "Erocoise", "Hiroquois", "Hyroquoise", "Irecoies", "Iriquois", "Iroquaes", "Irroquois", and "Yroquois", as the French transliterated the term into their own phonetic system.[4] In the French spoken at the time, this would have been pronounced as [irokwe] or [irokwɛ].[5] Over the years, several competing theories have been proposed for this name's ultimate origin. The earliest was by the Jesuit priest Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix, who wrote in 1744:

The name Iroquois is purely French, and is formed from the [Iroquoian-language] term Hiro or Hero, which means I have said—with which these Indians close all their addresses, as the Latins did of old with their dixi—and of Koué, which is a cry sometimes of sadness, when it is prolonged, and sometimes of joy, when it is pronounced shorter.[6]

In 1883, Horatio Hale wrote that Charlevoix's etymology was dubious, and that "no other nation or tribe of which we have any knowledge has ever borne a name composed in this whimsical fashion".[6] Hale suggested instead that the term came from Huron, and was cognate with Mohawk ierokwa- "they who smoke," or Cayuga iakwai- "a bear". In 1888, J.N.B. Hewitt expressed doubts that either of those words exist in the respective languages. He preferred the etymology from Montagnais irin "true, real" and ako "snake", plus the French -ois suffix. Later he revised this to Algonquin Iriⁿakhoiw.[7][8]

A more modern etymology was advocated by Gordon M. Day in 1968, elaborating upon Charles Arnaud from 1880. Arnaud had claimed that the word came from Montagnais irnokué, meaning "terrible man", via the reduced form irokue. Day proposed a hypothetical Montagnais phrase irno kwédač, meaning "a man, an Iroquois", as the origin of this term. For the first element irno, Day cites cognates from other attested Montagnais dialects: irinou, iriniȣ, and ilnu; and for the second element kwédač he suggests a relation to kouetakiou, kȣetat-chiȣin, and goéṭètjg – names used by neighboring Algonquian tribes to refer to the Iroquois, Hurons, and Laurentians.[9]

An entry published in the Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America attests the origin of Iroquois to "Iroqu," Algonquian for "rattlesnake".[10]

However, none of these etymologies gained widespread acceptance. By 1978 Ives Goddard wrote: "No such form is attested in any Indian language as a name for any Iroquoian group, and the ultimate origin and meaning of the name are unknown."[11]

More recently, Peter Bakker has proposed a Basque origin for "Iroquois". Basque fishermen and whalers are known to have frequented the waters of the Northeast in the 1500s, so much so that a Basque-based pidgin developed for communication with the Algonquian tribes of the region. Bakker claims that it is unlikely that "-quois" derives from a root specifically used to refer to the Iroquois, citing as evidence that several other Indian tribes of the region were known to the French by names terminating in the same element, e.g. "Armouchiquois", "Charioquois", "Excomminquois", and "Souriquois". He proposes instead that the word derives from hilokoa (via the intermediate form irokoa), from the Basque roots hil "to kill", ko (the locative genitive suffix), and a (the definite article suffix). In favor of an original form beginning with /h/, Bakker cites alternative spellings such as "hyroquois" sometimes found in documents from the period, and the fact that in the Southern dialect of Basque, the word hil is pronounced il. He also argues that the /l/ was rendered as /r/ since the former is not attested in the phonemic inventory of any language in the region (including Maliseet, which developed an /l/ later). Thus the word according to Bakker is translatable as "the killer people". It is similar to other terms used by Eastern Algonquian tribes to refer to their enemy the Iroquois, which translate as "murderers".[12][13]

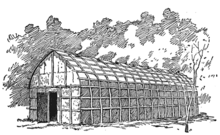

The Five Nations historically referred to themselves by the autonym, Haudenosaunee, meaning "People of the Longhouse".[14] This name is occasionally preferred by scholars of Native American history, who consider the name "Iroquois" derogatory.[15] The name derives from two phonetically similar but etymologically distinct words in the Seneca language: Hodínöhšö:ni:h, meaning "those of the extended house," and Hodínöhsö:ni:h, meaning "house builders".[16][17][11] The name "Haudenosaunee" first appears in English in Lewis Henry Morgan (1851), where it is written as Ho-dé-no-sau-nee. The spelling "Hotinnonsionni" is also attested from later in the nineteenth century.[18][19] An alternative designation, Ganonsyoni, is occasionally encountered as well,[20] from the Mohawk kanǫhsyǫ́·ni ("the extended house"), or from a cognate expression in a related Iroquoian language; in earlier sources it is variously spelled "Kanosoni", "akwanoschioni", "Aquanuschioni", "Cannassoone", "Canossoone", "Ke-nunctioni", or "Konossioni".[19] More transparently, the Iroquois confederacy is also often referred to simply as the Six Nations (or, for the period before the entry of the Tuscarora in 1722, the Five Nations).[21] The word is Rotinonsionni in the Mohawk language.[22]

Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois Confederacy or Haudenosaunee is believed to have been founded by the Peacemaker at an unknown date, estimated to have been sometime between 1450 and 1660, bringing together five distinct nations in the southern Great Lakes area into "The Great League of Peace".[23] Each nation within this Iroquoian confederacy had a distinct language, territory, and function in the League. Iroquois power at its peak extended into present-day Canada, westward along the Great Lakes and down both sides of the Allegheny mountains into present-day Virginia and Kentucky and into the Ohio Valley.

The League is governed by a Grand Council, an assembly of fifty chiefs or sachems, each representing one of the clans of one of the nations.[24]

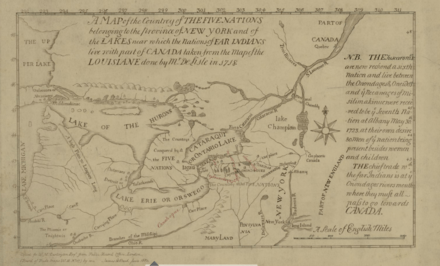

The original Iroquois League (as the French knew them) or Five Nations (as the British knew them), occupied large areas of present-day New York State up to the St. Lawrence River, west of the Hudson River, and south into northwestern Pennsylvania. From east to west, the League was composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations. In or close to 1722, the Tuscarora tribe joined the League,[25] having migrated from the Carolinas after being displaced by Anglo-European settlement. Also an Iroquoian-speaking people, the Tuscarora were accepted into the League, which became the Six Nations.

Other independent Iroquoian-speaking peoples, such as the Erie, Susquehannock, Huron (Wendat) and Wyandot, lived at various times along the St. Lawrence River, and around the Great Lakes. In the American Southeast, the Cherokee were an Iroquoian-language people who had migrated to that area centuries before European contact. None of these was part of the Haudenosaunee League. Those on the borders of Haudenosaunee territory in the Great Lakes region competed and warred with the nations of the League.

When Europeans first arrived in North America, the Haudenosaunee were based in what is now the northeastern United States, primarily in what is referred to today as Central New York and Western New York, west of the Hudson River and through the Finger Lakes region, and upstate New York along the St. Lawrence River area downstream to today's Montreal.[26]

French, Dutch and English colonists, both in New France (Canada) and what became the Thirteen Colonies, recognized a need to gain favor with the Iroquois people, who occupied a significant portion of lands west of the colonial settlements. Their first relations with them were for fur trading, which became highly lucrative for both sides. The colonists also sought to establish friendly relations to secure their settlement borders.

For nearly 200 years, the Iroquois were a powerful factor in North American colonial policy. Alignment with the Iroquois offered political and strategic advantages to the European colonies, but the Iroquois preserved considerable independence. Some of their people settled in mission villages along the St. Lawrence River, becoming more closely tied to the French. While they participated in French raids on Dutch and later English settlements, where some Mohawk and other Iroquois settled, in general the Iroquois resisted attacking their own peoples.

The Iroquois remained a large politically united Native American polity until the American Revolution, when the League kept its treaty promises to the British Crown. After their defeat, the British ceded Iroquois territory without bringing their allies to the negotiating table, and many Iroquois had to abandon their lands in the Mohawk Valley and elsewhere and relocate to the northern lands retained by the British. The Crown gave them land in compensation for the five million acres they had lost in the south, but it was not equivalent to earlier territory.

Modern scholars of the Iroquois distinguish between the League and the Confederacy.[27][28][29] According to this interpretation, the Iroquois League refers to the ceremonial and cultural institution embodied in the Grand Council, which still exists. The Iroquois Confederacy was the decentralized political and diplomatic entity that emerged in response to European colonization, which was dissolved after the British defeat in the American Revolutionary War.[27] Today's Iroquois/Six Nations people do not make any such distinction and use the terms interchangeably, preferring the name Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

Many of the Iroquois migrated to Canada, forced out of New York because of hostility to the British allies in the aftermath of a fierce war. Those remaining in New York were required to live mostly on reservations. In 1784, a total of 6,000 Iroquois faced 240,000 New Yorkers, with land-hungry New Englanders poised to migrate west. "Oneidas alone, who were only 600 strong, owned six million acres, or about 2.4 million hectares. Iroquoia was a land rush waiting to happen."[30] By the War of 1812, the Iroquois had lost control of considerable property.

The organization of the League has been compared to the modern-day systems of anarcho-communism[31] or libertarian socialism.[32]

History

Historiography

Previous research, containing the discovery of Iroquois tools and artifacts, suggests that the origin of the Iroquois was in Montreal, Canada, near the St. Lawrence River, where they were part of another group known as the Algonquin people. Their being driven out of Quebec and migration to New York was due to their unsuccessful war of independence from the Algonquin people. Knowledge of Iroquois history stems from Christian missionaries, Haudenosaunee oral tradition, archaeological evidence, accounts from Jesuit missionaries, and subsequent European historians. Historian Scott Stevens credits the early modern European value for the written word over oral cultural tradition as contributing to a racialized, prejudiced perspective in writings about the Iroquois through the 19th century.[33] The historiography of the Iroquois peoples is a topic of much debate, especially regarding the American colonial period.[34][35]

Jesuit accounts of the Iroquois portrayed them as savages because of comparisons to French culture; the Jesuits perceived them to lack government, law, letters, and religion.[36]:p.153 But the Jesuits made considerable effort to study their languages and cultures, and some came to respect them. A major problem with contemporary European sources from the 17th and 18th centuries, both French and British, was that Europeans, coming from a patriarchal society, did not understand the matrilineal kinship system of Iroquois society and the related power of women.[37] The Canadian historian D. Peter MacLeod, writing about the relationship between the Canadian Iroquois and the French in the time of the Seven Years' War, said:

Most critically, the importance of clan mothers, who possessed considerable economic and political power within Canadian Iroquois communities, was blithely overlooked by patriarchal European scribes. Those references that do exist, show clan mothers meeting in council with their male counterparts to take decisions regarding war and peace and joining in delegations to confront the Onontio [the Iroquois term for the French governor-general] and the French leadership in Montreal, but only hint at the real influence wielded by these women".[37]

Eighteenth-century English historiography focuses on the diplomatic relations with the Iroquois, supplemented by such images as John Verelst's Four Mohawk Kings, and publications such as the Anglo-Iroquoian treaty proceedings printed by Benjamin Franklin.[36]:p.161 One historical narrative persistent in the 19th and 20th centuries casts the Iroquois as "an expansive military and political power ... [who] subjugated their enemies by violent force and for almost two centuries acted as the fulcrum in the balance of power in colonial North America".[36]:p.148 Historian Scott Stevens noted that the Iroquois themselves began to influence the writing of their history in the 19th century, including Joseph Brant (Mohawk), and David Cusick (Tuscarora). John Arthur Gibson (Seneca, 1850–1912) was an important figure of his generation in recounting versions of Iroquois history in epics on the Peacemaker.[38] Notable women historians among the Iroquois emerged in the following decades, including Laura "Minnie" Kellog (Oneida, 1880–1949) and Alice Lee Jemison (Seneca, 1901–1964).[36]:p.162

Formation of the League

The Iroquois League was established prior to European contact, with the banding together of five of the many Iroquoian peoples who had emerged south of the Great Lakes.[39][lower-alpha 1] Many archaeologists and anthropologists believe that the League was formed about 1450,[40][41] though arguments have been made for an earlier date.[note1 1] One theory argues that the League formed shortly after a solar eclipse on August 31, 1142, an event thought to be expressed in oral tradition about the League's origins.[42][43][44] Some sources link an early origin of the Iroquois confederacy to the adoption of corn as a staple crop.[45]

Anthropologist Dean Snow argues that the archaeological evidence does not support a date earlier than 1450. He has said that recent claims for a much earlier date "may be for contemporary political purposes".[46]:p.231 In contrast, other scholars note that at the time when anthropological studies were made, researchers consulted only male informants, although the Iroquois people had distinct oral traditions held by males and females. Thus half of the historical story, that told by women, was lost.[47] For this reason, origin tales tend to emphasize Deganawidah and Hiawatha, while the role of Jigonsaseh largely remains unknown because this part of the oral history was held by women.[47]

According to oral traditions, the League was formed through the efforts of two men and one woman. They were Dekanawida, sometimes known as the Great Peacemaker, Hiawatha, and Jigonhsasee, known as the Mother of Nations, whose home acted as a sort of United Nations. They brought the Peacemaker's message, known as the Great Law of Peace, to the squabbling Iroquoian nations, who were fighting, raiding and feuding with one another and other tribes, both Algonkian and Iroquoian. Five nations originally joined as the League, giving rise to the many historic references to Five Nations of the Iroquois[lower-alpha 2] or as often, just The Five Nations.[39] With the addition of the southern Tuscarora in the 18th century, these original five tribes are the ones that still compose the Haudenosaunee in the early 21st century: the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca.

According to legend, an evil Onondaga chieftain named Tadodaho was the last converted to the ways of peace by The Great Peacemaker and Hiawatha. He was offered the position as the titular chair of the League's Council, representing the unity of all nations of the League.[48] This is said to have occurred at Onondaga Lake near present-day Syracuse, New York. The title Tadodaho is still used for the League's chair, the fiftieth chief who sits with the Onondaga in council.

The Iroquois subsequently created a highly egalitarian society. One British colonial administrator declared in 1749 that the Iroquois had "such absolute Notions of Liberty that they allow no Kind of Superiority of one over another, and banish all Servitude from their Territories".[49] With the formation of the League, internal conflicts were minimized. The council of fifty ruled on disputes, seeking consensus in their decisions. Raids within the member tribes ended, and they directed warfare against competitors. This allowed the Iroquois to increase in numbers while their rivals declined. The political cohesion of the Iroquois rapidly became one of the strongest forces in 17th- and 18th-century northeastern North America. The confederacy did not speak for all five tribes, which continued to act independently. Around 1678, the council began to exert more power in negotiations with the colonial governments of Pennsylvania and New York, and the Iroquois became very adroit at diplomacy, playing off the French against the British as individual tribes had earlier played the Swedes, Dutch, and English.[39]

Iroquoian-language peoples were involved in warfare and trading with nearby members of the Iroquois League.[39] The explorer Robert La Salle in the 17th century identified the Mosopelea as among the Ohio Valley peoples defeated by the Iroquois in the early 1670s.[50] The Erie and peoples of the upper Allegheny valley declined earlier during the Beaver Wars. By 1676 the Susquehannock[lower-alpha 3] were known to be broken as a power from the effects of three years of epidemic disease, war with the Iroquois, and frontier battles, as settlers took advantage of the weakened tribe.[39]

According to one theory of early Iroquois history, after becoming united in the League, the Iroquois invaded the Ohio River Valley in the territories that would become the eastern Ohio Country down as far as present-day Kentucky to seek additional hunting grounds. They displaced about 1200 Siouan-speaking tribepeople of the Ohio River valley, such as the Quapaw (Akansea), Ofo (Mosopelea), and Tutelo and other closely related tribes out of the region. These tribes migrated to regions around the Mississippi River and the piedmont regions of the east coast.[51]

Other Iroquoian-language peoples,[52] including the populous Wyandot (Huron), with related social organization and cultures, became extinct as tribes as a result of disease and war.[lower-alpha 4] They did not join the League when invited[lower-alpha 5] and were much reduced after the Beaver Wars and high mortality from Eurasian infectious diseases. While the First Nations and Native Americans sometimes tried to remain neutral in the various colonial frontier wars, some also allied with one nation or another, through the French and Indian War. The Six Nations were split in their alliances between the French and British in that war, the North American front of the Seven Years' War. In warfare the tribes were decentralized, and often bands acted independently.

Expansion

In Reflections in Bullough's Pond, historian Diana Muir argues that the pre-contact Iroquois were an imperialist, expansionist culture whose cultivation of the corn/beans/squash agricultural complex enabled them to support a large population. They made war primarily against neighboring Algonquian peoples. Muir uses archaeological data to argue that the Iroquois expansion onto Algonquian lands was checked by the Algonquian adoption of agriculture. This enabled them to support their own populations large enough to have sufficient warriors to defend against the threat of Iroquois conquest.[53] The People of the Confederacy dispute whether any of this historical interpretation relates to the League of the Great Peace which they contend is the foundation of their heritage.

The Iroquois may be the Kwedech described in the oral legends of the Mi'kmaq nation of Eastern Canada. These legends relate that the Mi'kmaq in the late pre-contact period had gradually driven their enemies – the Kwedech – westward across New Brunswick, and finally out of the Lower St. Lawrence River region. The Mi'kmaq named the last-conquered land Gespedeg or "last land," from which the French derived Gaspé. The "Kwedech" are generally considered to have been Iroquois, specifically the Mohawk; their expulsion from Gaspé by the Mi'kmaq has been estimated as occurring c. 1535–1600.[54]

Around 1535, Jacques Cartier reported Iroquoian-speaking groups on the Gaspé peninsula and along the St. Lawrence River. Archeologists and anthropologists have defined the St. Lawrence Iroquoians as a distinct and separate group (and possibly several discrete groups), living in the villages of Hochelaga and others nearby (near present-day Montreal), which had been visited by Cartier. By 1608, when Samuel de Champlain visited the area, that part of the St. Lawrence River valley had no settlements, but was controlled by the Mohawk as a hunting ground. The fate of the Iroquoian people that Cartier encountered remains a mystery, and all that can be stated for certain is when Champlain arrived, they were gone.[55] On the Gaspé peninsula, Champlain encountered Algonquian-speaking groups. The precise identity of any of these groups is still debated. On July 29, 1609, Champlain assisted his allies in defeating a Mohawk war party by the shores of what is now called Lake Champlain, and again in June 1610, Champlain fought against the Mohawks.[56]

The Iroquois became well known in the southern colonies in the 17th century by this time. After the first English settlement in Jamestown, Virginia (1607), numerous 17th-century accounts describe a powerful people known to the Powhatan Confederacy as the Massawomeck, and to the French as the Antouhonoron. They were said to come from the north, beyond the Susquehannock territory. Historians have often identified the Massawomeck / Antouhonoron as the Haudenosaunee.

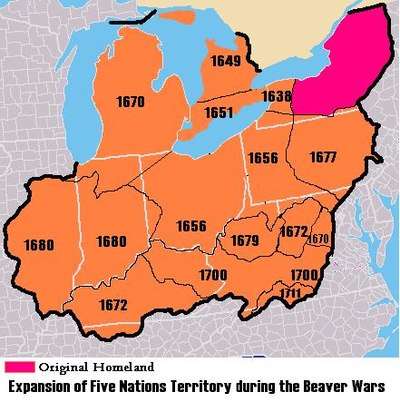

In 1649, an Iroquois war party, consisting mostly of Senecas and Mohawks, destroyed the Huron village of Wendake. In turn, this ultimately resulted in the breakup of the Huron nation. With no northern enemy remaining, the Iroquois turned their forces on the Neutral Nations on the north shore of Lakes Erie and Ontario, the Susquehannocks, their southern neighbor. Then they destroyed other Iroquoian-language tribes, including the Erie, to the west, in 1654, over competition for the fur trade.[57] Then they destroyed the Mohicans. After their victories, they reigned supreme in an area from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean; from the St. Lawrence River to the Chesapeake Bay.[58]

At that time the Iroquois numbered about 10,000, insufficient to offset the European population of 75,000 by 1660, 150,000 by 1680 and 250,000 by 1700. Michael O. Varhola has argued their success in conquering and subduing surrounding nations had paradoxically weakened a Native response to European growth, thereby becoming victims of their own success.[58]

The Five Nations of the League established a trading relationship with the Dutch at Fort Orange (modern Albany, New York), trading furs for European goods, an economic relationship that profoundly changed their way of life and led to much over-hunting of beavers.[59]

Between 1665 and 1670, the Iroquois established seven villages on the northern shores of Lake Ontario in present-day Ontario, collectively known as the "Iroquois du Nord" villages. The villages were all abandoned by 1701.[60]

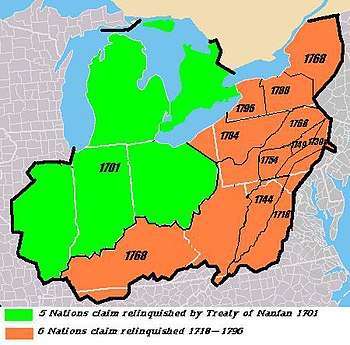

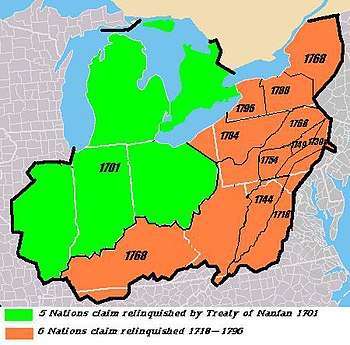

Over the years 1670–1710, the Five Nations achieved political dominance of much of Virginia west of the Fall Line and extending to the Ohio River valley in present-day West Virginia and Kentucky. As a result of the Beaver Wars, they pushed Siouan-speaking tribes out and reserved the territory as a hunting ground by right of conquest. They finally sold the British colonists their remaining claim to the lands south of the Ohio in 1768 at the Treaty of Fort Stanwix.

Beaver Wars

Beginning in 1609, the League engaged in the decades-long Beaver Wars against the French, their Huron allies, and other neighboring tribes, including the Petun, Erie, and Susquehannock.[59] Trying to control access to game for the lucrative fur trade, they invaded the Algonquian peoples of the Atlantic coast (the Lenape or Delaware), the Anishinaabe of the boreal Canadian Shield region, and not infrequently the English colonies as well. During the Beaver Wars, they were said to have defeated and assimilated the Huron (1649), Petun (1650), the Neutral Nation (1651),[61][62] Erie Tribe (1657), and Susquehannock (1680).[63] The traditional view is that these wars were a way to control the lucrative fur trade to purchase European goods on which they had become dependent.[64] [65]

Recent scholarship has elaborated on this view, arguing that the Beaver Wars were an escalation of the Iroquoian tradition of "Mourning Wars".[66] This view suggests that the Iroquois launched large-scale attacks against neighboring tribes to avenge or replace the many dead from battles and smallpox epidemics.

In 1628, the Mohawk defeated the Mahican to gain a monopoly in the fur trade with the Dutch at Fort Orange (present-day Albany), New Netherland. The Mohawk would not allow northern native peoples to trade with the Dutch.[59] By 1640, there were almost no beavers left on their lands, reducing the Iroquois to middlemen in the fur trade between Indian peoples to the west and north, and Europeans eager for the valuable thick beaver pelts.[59] In 1645, a tentative peace was forged between the Iroquois and the Huron, Algonquin, and French.

In 1646, Jesuit missionaries at Sainte-Marie among the Hurons went as envoys to the Mohawk lands to protect the precarious peace. Mohawk attitudes toward the peace soured while the Jesuits were traveling, and their warriors attacked the party en route. The missionaries were taken to the village of Ossernenon (near present-day Auriesville, New York), where the moderate Turtle and Wolf clans recommended setting them free, but angry members of the Bear clan killed Jean de Lalande, and Isaac Jogues on October 18, 1646.[67] The Catholic Church has commemorated the two French priests and Jesuit lay Brother René Goupil (killed September 29, 1642) [68] as among the eight North American Martyrs.

In 1649 during the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois used recently purchased Dutch guns to attack the Huron, allies of the French. These attacks, primarily against the Huron towns of Taenhatentaron (St. Ignace[69]) and St. Louis[70] in what is now Simcoe County, Ontario were the final battles that effectively destroyed the Huron Confederacy.[71] The Jesuit missions in Huronia on the shores of Georgian Bay were abandoned in the face of the Iroquois attacks, with the Jesuits leading the surviving Hurons east towards the French settlements on the St. Lawrence.[67] The Jesuit Relations expressed some amazement that the Five Nations had been able to dominate the area "for five hundred leagues around, although their numbers are very small".[67] From 1651 to 1652, the Iroquois attacked the Susquehannock, to their south in present-day Pennsylvania, without sustained success.

In the early 17th century, the Iroquois Confederacy was at the height of its power, with a total population of about 12,000.[72] In 1653 the Onondaga Nation extended a peace invitation to New France. An expedition of Jesuits, led by Simon Le Moyne, established Sainte Marie de Ganentaa in 1656 in their territory. They were forced to abandon the mission by 1658 as hostilities resumed, possibly because of the sudden death of 500 native people from an epidemic of smallpox, a European infectious disease to which they had no immunity.

From 1658 to 1663, the Iroquois were at war with the Susquehannock and their Lenape and Province of Maryland allies. In 1663, a large Iroquois invasion force was defeated at the Susquehannock main fort. In 1663, the Iroquois were at war with the Sokoki tribe of the upper Connecticut River. Smallpox struck again, and through the effects of disease, famine, and war, the Iroquois were under threat of extinction. In 1664, an Oneida party struck at allies of the Susquehannock on Chesapeake Bay.

In 1665, three of the Five Nations made peace with the French. The following year, the Governor-General of New France, the Marquis de Tracy, sent the Carignan regiment to confront the Mohawk and Oneida.[73] The Mohawk avoided battle, but the French burned their villages, which they referred to as "castles", and their crops.[73] In 1667, the remaining two Iroquois Nations signed a peace treaty with the French and agreed to allow missionaries to visit their villages. The French Jesuit missionaries were known as the "black-robes" to the Iroquois, who began to urge that Catholic converts should relocate to the village of Caughnawga outside of Montreal.[73] This treaty lasted for 17 years.

1670–1701

Around 1670, the Iroquois drove the Siouan-speaking Mannahoac tribe out of the northern Virginia Piedmont region, and began to claim ownership of the territory. In 1672, they were defeated by a war party of Susquehannock, and the Iroquois appealed to the French Governor Frontenac for support:

It would be a shame for him to allow his children to be crushed, as they saw themselves to be ... they not having the means of going to attack their fort, which was very strong, nor even of defending themselves if the others came to attack them in their villages.[74]

Some old histories state that the Iroquois defeated the Susquehannock but this is undocumented and doubtful.[74] In 1677, the Iroquois adopted the majority of the Iroquoian-speaking Susquehannock into their nation.[75]

In January 1676, the Governor of New York colony, Edmund Andros, sent a letter to the chiefs of the Iroquois asking for their help in King Philip's War, as the English colonists in New England were having much difficulty fighting the Wampanoag led by Metacom. In exchange for precious guns from the English, an Iroquois war party devastated the Wampanoag in February 1676, destroying villages and food stores while taking many prisoners.[76]

By 1677, the Iroquois formed an alliance with the English through an agreement known as the Covenant Chain. By 1680, the Iroquois Confederacy was in a strong position, having eliminated the Susquehannock and the Wampanoag, taken vast numbers of captives to augment their population, and secured an alliance with the English supplying guns and ammunition.[77] Together the allies battled to a standstill the French and their allies the Hurons, traditional foes of the Confederacy. The Iroquois colonized the northern shore of Lake Ontario and sent raiding parties westward all the way to Illinois Country. The tribes of Illinois were eventually defeated, not by the Iroquois, but by the Potawatomi.

In 1679, the Susquehannock, with Iroquois help, attacked Maryland's Piscataway and Mattawoman allies. Peace was not reached until 1685. During the same period, French Jesuit missionaries were active in Iroquoia, which led to a voluntary mass relocation of many Haudenosaunee to the St. Lawrence valley at Kahnawake and Kanesatake near Montreal. It was the intention of the French to use the Catholic Haudenosaunee in the St. Lawrence valley as a buffer to keep the English-allied Haudenosaunee tribes, in what is now upstate New York, away from the center of the French fur trade in Montreal. The attempts of both the English and the French to make use of their Haudenosaunee allies were foiled, as the two groups of Haudenosaunee showed a "profound reluctance to kill one another".[78] Following the move of the Catholic Iroquois to the St. Lawrence valley, historians commonly describe the Iroquois living outside of Montreal as the Canadian Iroquois, while those remaining in their historical heartland in modern upstate New York are described as the League Iroquois.[79]

In 1684, the governor of New France, Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre, decided to launch a punitive expedition against the Seneca, who were attacking French and Algonquian fur traders in the Mississippi river valley, and asked for the Catholic Haudenosaunee to contribute fighting men.[80] La Barre's expedition ended in fiasco in September 1684 when influenza broke out among the French troupes de la Marine while the Canadian Iroquois warriors refused to fight, instead only engaging in battles of insults with the Seneca warriors.[81] King Louis XIV of France was not amused when he heard of La Barre's failure, which led to his replacement with Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville, Marquis de Denonville (governor 1685–1689), who arrived in August with orders from the Sun King to crush the Haudenosaunee confederacy and uphold the honor of France even in the wilds of North America.[81]

In 1684, the Iroquois again invaded Virginia and Illinois territory and unsuccessfully attacked French outposts in the latter. Trying to reduce warfare in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, later that year the Virginia Colony agreed in a conference at Albany to recognize the Iroquois' right to use the North-South path, known as the Great Warpath, running east of the Blue Ridge, provided they did not intrude on the English settlements east of the Fall Line.

In 1687, the Marquis de Denonville set out for Fort Frontenac (modern Kingston, Ontario) with a well-organized force. In July 1687 Denonville took with him on his expedition a mixed force of troupes de la Marine, French-Canadian militiamen, and 353 Indian warriors from the Jesuit mission settlements, including 220 Haudenosaunee.[81] They met under a flag of truce with 50 hereditary sachems from the Onondaga council fire, on the north shore of Lake Ontario in what is now southern Ontario.[81] Denonville recaptured the fort for New France and seized, chained, and shipped the 50 Iroquois chiefs to Marseilles, France, to be used as galley slaves.[81] Several of the Catholic Haudenosaunee were outraged at this treachery to a diplomatic party, which led to least 100 of them to desert to the Seneca.[82] Denonville justified enslaving the people he encountered, saying that as a "civilized European" he did not respect the customs of "savages" and would do as he liked with them. On August 13, 1687, an advance party of French soldiers walked into a Seneca ambush and were nearly killed to a man; however the Seneca fled when the main French force came up. The remaining Catholic Haudenosaunee warriors refused to pursue the retreating Seneca.[81]

Denonville ravaged the land of the Seneca, landing a French armada at Irondequoit Bay, striking straight into the seat of Seneca power, and destroying many of its villages. Fleeing before the attack, the Seneca moved farther west, east and south down the Susquehanna River. Although great damage was done to their homeland, the Senecas' military might was not appreciably weakened. The Confederacy and the Seneca developed an alliance with the English who were settling in the east. The destruction of the Seneca land infuriated the members of the Iroquois Confederacy. On August 4, 1689, they retaliated by burning down Lachine, a small town adjacent to Montreal. Fifteen hundred Iroquois warriors had been harassing Montreal defenses for many months prior to that.

They finally exhausted and defeated Denonville and his forces. His tenure was followed by the return of Frontenac for the next nine years (1689–1698). Frontenac had arranged a new strategy to weaken the Iroquois. As an act of conciliation, he located the 13 surviving sachems of the 50 originally taken and returned with them to New France in October 1689. In 1690, Frontenac destroyed the village of Schenectady and in 1693 burned down three Mohawk villages and took 300 prisoners.[83]

In 1696, Frontenac decided to take the field against the Iroquois, despite being seventy-six years of age. He decided to target the Oneida and Onondaga, instead of the Mohawk who had been the favorite enemies of the French.[83] On July 6, he left Lachine at the head of a considerable force and traveled to the village of the Onondaga, where he arrived a month later. With support from the French, the Algonquian nations drove the Iroquois out of the territories north of Lake Erie and west of present-day Cleveland, Ohio, regions which they had conquered during the Beaver Wars.[84] In the meantime, the Iroquois had abandoned their villages. As pursuit was impracticable, the French army commenced its return march on August 10. Under Frontenac's leadership, the Canadian militia became increasingly adept at guerrilla warfare, taking the war into Iroquois territory and attacking a number of English settlements. The Iroquois never threatened the French colony again.[85]

During King William's War (North American part of the War of the Grand Alliance), the Iroquois were allied with the English. In July 1701, they concluded the "Nanfan Treaty", deeding the English a large tract north of the Ohio River. The Iroquois claimed to have conquered this territory 80 years earlier. France did not recognize the treaty, as it had settlements in the territory at that time and the English had virtually none. Meanwhile, the Iroquois were negotiating peace with the French; together they signed the Great Peace of Montreal that same year.

French and Indian Wars

After the 1701 peace treaty with the French, the Iroquois remained mostly neutral. During the course of the 17th century, the Iroquois had acquired a fearsome reputation among the Europeans, and it was the policy of the Six Nations to use this reputation to play off the French against the British in order to extract the maximum amount of material rewards.[86] In 1689, the English Crown provided the Six Nations goods worth £100 in exchange for help against the French, in the year 1693 the Iroquois had received goods worth £600, and in the year 1701 the Six Nations had received goods worth £800.[87]

During Queen Anne's War (North American part of the War of the Spanish Succession), they were involved in planned attacks against the French. Peter Schuyler, mayor of Albany, arranged for three Mohawk chiefs and a Mahican chief (known incorrectly as the Four Mohawk Kings) to travel to London in 1710 to meet with Queen Anne in an effort to seal an alliance with the British. Queen Anne was so impressed by her visitors that she commissioned their portraits by court painter John Verelst. The portraits are believed to be the earliest surviving oil portraits of Aboriginal peoples taken from life.[88]

In the first quarter of the 18th century, the Iroquoian-speaking Tuscarora fled north from the pressure of British colonization of North Carolina and intertribal warfare; they had been subject to having captives sold into Indian slavery. They petitioned to become the sixth nation of the Iroquois Confederacy. This was a non-voting position, but they gained the protection of the Haudenosaunee.

The Iroquois program toward the defeated tribes favored assimilation within the 'Covenant Chain' and Great Law of Peace, over wholesale slaughter. Both the Lenni Lenape, and the Shawnee were briefly tributary to the Six Nations, while subjected Iroquoian populations emerged in the next period as the Mingo, speaking a dialect like that of the Seneca, in the Ohio region. During the War of Spanish Succession, known to Americans as "Queen Anne's War", the Iroquois remained neutral, through leaning towards the British.[83] Anglican missionaries were active with the Iroquois and devised a system of writing for them.[83]

In 1721 and 1722, Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood of Virginia concluded a new Treaty at Albany with the Iroquois, renewing the Covenant Chain and agreeing to recognize the Blue Ridge as the demarcation between the Virginia Colony and the Iroquois. But, as European settlers began to move beyond the Blue Ridge and into the Shenandoah Valley in the 1730s, the Iroquois objected. Virginia officials told them that the demarcation was to prevent the Iroquois from trespassing east of the Blue Ridge, but it did not prevent English from expanding west. Tensions increased over the next decades, and the Iroquois were on the verge of going to war with the Virginia Colony. In 1743, Governor Gooch paid them the sum of 100 pounds sterling for any settled land in the Valley that was claimed by the Iroquois. The following year at the Treaty of Lancaster, the Iroquois sold Virginia all their remaining claims in the Shenandoah Valley for 200 pounds in gold.[89]

During the French and Indian War (the North American theater of the Seven Years' War), the League Iroquois sided with the British against the French and their Algonquian allies, who were traditional enemies. The Iroquois hoped that aiding the British would also bring favors after the war. Few Iroquois warriors joined the campaign. By contrast, the Canadian Iroquois supported the French.

In 1711, refugees from is now southern-western Germany known as the Palatines appealed to the Iroquois clan mothers for permission to settle on their land.[90] By spring of 1713, about 150 Palatine families had leased land from the Iroquois.[91] The Iroquois taught the Palatines how to grow "the Three Sisters" as they called their staple crops of beans, corn and squash and where to find edible nuts, roots and berries.[91] In return, the Palatines taught the Iroquois how to grow wheat and oats, and how to use iron ploughs and hoes to farm.[91] As a result of the money earned from land rented to the Palatines, the Iroquois elite gave up living in longhouses and started living in European style houses, having an income equal to a middle-class English family.[91] By the middle of the 18th century, a multi-cultural world had emerged with the Iroquois living alongside German and Scots-Irish settlers.[92] The settlements of the Palatines were intermixed with the Iroquois villages.[93] In 1738, an Irishman, William Johnson, who was successful as a fur trader, settled with the Iroquois.[94] Johnson who become very rich from the fur trade and land speculation, learned the languages of the Iroquois while bedding as many of their women as possible, and become the main intermediary between the British and the League.[94] In 1745, Johnson was appointed the Northern superintendent of Indian Affairs, formalizing his position.[95]

On July 9, 1755, a force of British Army regulars and the Virginia militia under General Edward Braddock advancing into the Ohio river valley was almost completely destroyed by the French and their Indian allies at the Battle of the Monongahela.[95] Johnson, who had the task of enlisting the League Iroquois on the British side, led a mixed Anglo-Iroquois force to victory at Lac du St Sacrement, known to the British as Lake George.[95] In the Battle of Lake George, a group of Catholic Mohawk (from Kahnawake) and French forces ambushed a Mohawk-led British column; the Mohawk were deeply disturbed as they had created their confederacy for peace among the peoples and had not had warfare against each other. Johnson attempted to ambush a force of 1,000 French troops and 700 Canadian Iroquios under the command of Baron Dieskau, who beat off the attack and killed the old Mohawk war chief, Peter Hendricks.[95] On September 8, 1755, Diskau attacked Johnson's camp, but was repulsed with heavy losses.[95] Though the Battle of Lake George was a British victory, the heavy losses taken by the Mohawk and Oneida at the battle caused the League to declare neutrality in the war.[95] Despite Johnson's best efforts, the League Iroquois remained neutral for next several years, and a series of French victories at Oswego, Louisbourg, Fort William Henry and Fort Carillon ensured the League Iroquois would not fight on what appeared to be the losing side.[96]

In February 1756, the French learned from a spy, Oratory, an Oneida chief, that the British were stockpiling supplies at the Oneida Carrying Place, a crucial portage between Albany and Oswego to support an offensive in the spring into what is now Ontario. As the frozen waters melted south of Lake Ontario on average two weeks before the waters did north of Lake Ontario, the British would be able to move against the French bases at Fort Frontenac and Fort Niagara before the French forces in Montreal could come to their relief, which from the French perspective necessitated a preemptive strike at the Oneida Carrying Place in the winter.[97] To carry out this strike, the Marquis de Vaudreuil, the Governor-General of New France, assigned the task to Gaspard-Joseph Chaussegros de Léry, an officer of the troupes de le Marine, who required and received the assistance of the Canadian Iroquois to guide him to the Oneida Carrying Place.[98] The Canadian Iroquois joined the expedition, which left Montreal on February 29, 1756 on the understanding that they would only fight against the British, not the League Iroquois, and they would not be assaulting a fort.[99]

On March 13, 1756, an Oswegatchie Indian traveler informed the expedition that the British had built two forts at the Oneida Carrying Place, which caused the majority of the Canadian Iroquois to want to turn back, as they argued the risks of assaulting a fort would mean too many casualties, and many did in fact abandon the expedition.[100] On March 26, 1756, Léry's force of troupes de le Marine and French-Canadian militiamen, who had not eaten for two days, received much needed food when the Canadian Iroquois ambushed a British wagon train bringing supplies to Fort William and Fort Bull.[101] As far as the Canadian Iroquois were concerned, the raid was a success as they captured 9 wagons full of supplies and took 10 prisoners without losing a man, and for them, engaging in a frontal attack against the two wooden forts as Léry wanted to do was irrational.[102] The Canadian Iroquois informed Léry "if I absolutely wanted to die, I was the master of the French, but they were not going to follow me".[103] In the end, about 30 Canadian Iroquois reluctantly joined Léry's attack on Fort Bull on the morning of March 27, 1756, when the French and their Indian allies stormed the fort, finally smashing their way in through the main gate with a battering ram at noon.[104] Of the 63 people in Fort Bull, half of whom were civilians, only 3 soldiers, one carpenter and one woman survived the Battle of Fort Bull as Léry reported "I could not restrain the ardor of the soldiers and the Canadians. They killed everyone they encountered".[105] Afterwards, the French destroyed all of the British supplies and Fort Bull itself, which secured the western flank of New France. On the same day, the main force of the Canadian Iroquois ambushed a relief force from Fort William coming to the aid of Fort Bull, and did not slaughter their prisoners as the French did at Fort Bull; for the Iroquois, prisoners were very valuable as they increased the size of the tribe.[106]

The crucial difference between the European and First Nations way of war was that Europe had millions of people, which meant that British and French generals were willing to see thousands of their own men die in battle in order to secure victory as their losses could always be made good; by contrast, the Iroquois had a considerably smaller population, and could not afford heavy losses, which could cripple a community. The Iroquois custom of "Mourning wars" to take captives who would become Iroquois reflected the continual need for more people in the Iroquois communities. Iroquois warriors were brave, but would only fight to the death if necessary, usually to protect their women and children; otherwise, the crucial concern for Iroquois chiefs was always to save manpower.[107] The Canadian historian D. Peter MacLeod wrote that the Iroquois way of war was based on their hunting philosophy, where a successful hunter would bring down an animal efficiently without taking any losses to his hunting party, and in the same way, a successful war leader would inflict losses on the enemy without taking any losses in return.[108]

The Iroquois only entered the war on the British side again in late 1758 after the British took Louisbourg and Fort Frontenac.[96] At the Treaty of Fort Easton in October 1758, the Iroquois forced the Lenape and Shawnee who had been fighting for the French to declare neutrality.[96] In July 1759, the Iroquois helped Johnson take Fort Niagara.[96] In the ensuing campaign, the League Iroquois assisted General Jeffrey Amherst as he took various French forts by the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence valley as he advanced towards Montreal, which he took in September 1760.[96] The British historian Michael Johnson wrote the Iroquois had "played a major supporting role" in the final British victory in the Seven Years' War.[96] In 1763, Johnson left his old home of Fort Johnson for the lavish estate, which he called Johnson Hall, which become a center of social life in the region.[96] Johnson was close to two white families, the Butlers and the Croghans, and three Mohawk families, the Brants, the Hills, and the Peters.[96]

After the war, to protect their alliance, the British government issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding Anglo-European (white) settlements beyond the Appalachian Mountains. Colonists largely ignored the order, and the British had insufficient soldiers to enforce it.

Faced with confrontations, the Iroquois agreed to adjust the line again in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768). Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District, had called the Iroquois nations together in a grand conference in western New York, which a total of 3,102 Indians attended.[30] They had long had good relations with Johnson, who had traded with them and learned their languages and customs. As Alan Taylor noted in his history, The Divided Ground: Indians, Settlers, and the Northern Borderland of the American Revolution (2006), the Iroquois were creative and strategic thinkers. They chose to sell to the British Crown all their remaining claim to the lands between the Ohio and Tennessee rivers, which they did not occupy, hoping by doing so to draw off English pressure on their territories in the Province of New York.[30]

American Revolution

_by_Charles_Bird_King.jpg)

During the American Revolution, the Iroquois first tried to stay neutral. The Reverend Samuel Kirkland, a Congregational minister working as a missionary, pressured the Oneida and the Tuscarora for a pro-American neutrality while Guy Johnson and his cousin John Johnson pressured the Mohawk, the Cayuga and the Seneca to fight for the British.[109] Pressed to join one side or the other, the Tuscarora and the Oneida sided with the colonists, while the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga remained loyal to Great Britain, with whom they had stronger relationships. Joseph Louis Cook offered his services to the United States and received a Congressional commission as a lieutenant colonel—the highest rank held by any Native American during the war.[110] The Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant together with John Butler and John Johnson raised racially mixed forces of irregulars to fight for the Crown.[111] Molly Brant had been the common-law wife of Sir William Johnson, and it was through her patronage that her brother Joseph came to be a war chief.[112]

The Mohawk war chief Joseph Brant, other war chiefs, and British allies conducted numerous operations against frontier settlements in the Mohawk Valley, including the Cherry Valley massacre, destroying many villages and crops, and killing and capturing inhabitants. The destructive raids by Brant and other Loyalists led to appeals to Congress for help.[112] The Continentals retaliated and in 1779, George Washington ordered the Sullivan Campaign, led by Col. Daniel Brodhead and General John Sullivan, against the Iroquois nations to "not merely overrun, but destroy", the British-Indian alliance. They burned many Iroquois villages and stores throughout western New York; refugees moved north to Canada. By the end of the war, few houses and barns in the valley had survived the warfare. In the aftermath of the Sullivan expedition, Brant visited Quebec City to ask General Sir Frederick Haildmand for assurances that the Mohawk and the other Loyalist Iroquois would receive a new homeland in Canada as compensation for their loyalty to the Crown if the British should lose.[112]

The American Revolution was a war that caused a great divide between the colonists between Patriots and Loyalists and a large proportion (30-35% who were neutral); it caused a divide between the colonies and Great Britain, and it also caused a rift that would break the Iroquois Confederacy. At the onset of the Revolution, the Iroquois Confederacy's Six Nations attempted to take a stance of neutrality. However, almost inevitably, the Iroquois nations eventually had to take sides in the conflict. It is easy to see how the American Revolution would have caused conflict and confusion among the Six Nations. For years they had been used to thinking about the English and their colonists as one and the same people. In the American Revolution, the Iroquois Confederacy now had to deal with relationships between two governments.[113]

The Iroquois Confederation's population had changed significantly since the arrival of Europeans. Disease had reduced their population to a fraction of what it had been in the past.[114] Therefore, it was in their best interest to be on the good side of whoever would prove to be the winning side in the war, for the winning side would dictate how future relationships would be with the Iroquois in North America. Dealing with two governments made it hard to maintain a neutral stance, because the governments could get jealous easily if the Confederacy was interacting or trading more with one side over the other, or even if there was simply a perception of favoritism. Because of this challenging situation, the Six Nations had to choose sides. The Oneida and Tuscarora decided to support the American colonists, while the rest of the Iroquois League (the Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, and Seneca) sided with the British and their Loyalists among the colonists.

There were many reasons that the Six Nations could not remain neutral and uninvolved in the Revolutionary War. One of these is simple proximity; the Iroquois Confederacy was too close to the action of the war to not be involved. The Six Nations were very discontented with the encroachment of the English and their colonists upon their land. They were particularly concerned with the border established in the Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768.[115]

During the American Revolution, the authority of the British government over the frontier was hotly contested. The colonists tried to take advantage of this as much as possible by seeking their own profit and claiming new land. In 1775, the Six Nations were still neutral when "a Mohawk person was killed by a Continental soldier".[114]:370 Such a case shows how the Six Nations' proximity to the war drew them into it. They were concerned about being killed, and about their lands being taken from them. They could not show weakness and simply let the colonists and British do whatever they wanted. Many of the English and colonists did not respect the treaties made in the past. "A number of His Majesty's subjects in the American colonies viewed the proclamation as a temporary prohibition which would soon give way to the opening of the area for settlement ... and that it was simply an agreement to quiet the minds of the Indians".[115] The Six Nations had to take a stand to show that they would not accept such treatment, and they looked to build a relationship with a government that would respect their territory.

In addition to being in close proximity to the war, the new lifestyle and economics of the Iroquois Confederacy since the arrival of the Europeans in North America made it nearly impossible for the Iroquois to isolate themselves from the conflict. By this time, the Iroquois had become dependent upon the trade of goods from the English and colonists, and had adopted many European customs, tools, and weapons. For example, they were increasingly dependent on firearms for hunting.[116] After becoming so reliant, it would have been hard to even consider cutting off trade that brought goods that were a central part of everyday life.

As Barbara Graymont stated, "Their task was an impossible one to maintain neutrality. Their economies and lives had become so dependent on each other for trading goods and benefits it was impossible to ignore the conflict. Meanwhile they had to try and balance their interactions with both groups. They did not want to seem as they were favoring one group over the other, because of sparking jealousy and suspicion from either side". Furthermore, the English had made many agreements with the Six Nations over the years, yet most of the Iroquois' day-to-day interaction had been with the colonists. This made it a confusing situation for the Iroquois because they could not tell who the true heirs of the agreement were, and couldn't know if agreements with England would continue to be honored by the colonists if they were to win independence.

Supporting either side in the Revolutionary War was a complicated decision. Each nation individually weighed their options to come up with a final stance that ultimately broke neutrality and ended the collective agreement of the Confederation. The British were clearly the most organized, and seemingly most powerful. In many cases, the British presented the situation to the Iroquois as the colonists just being "naughty children". On the other, the Iroquois considered that "the British government was three thousand miles away. This placed them at a disadvantage in attempting to enforce both the Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaty at Fort Stanwix 1768 against land hungry frontiersmen."[116]:49 In other words, even though the British were the strongest and best organized faction, the Six Nations had concerns about whether they would truly be able to enforce their agreements from so far away.

The Iroquois also had concerns about the colonists. The British asked for Iroquois support in the war. "In 1775, the Continental Congress sent a delegation to the Iroquois in Albany to ask for their neutrality in the war coming against the British".[114]:370 It had been clear in prior years that the colonists had not been respectful of the land agreements made in 1763 and 1768. The Iroquois Confederacy was particularly concerned over the possibility of the colonists winning the war, for if a revolutionary victory were to occur, the Iroquois very much saw it as the precursor to their lands being taken away by the victorious colonists, who would no longer have the British Crown to restrain them.[117] Continental army officers such as George Washington had attempted to destroy the Iroquois.[114]

On a contrasting note, it was the colonists who had formed the most direct relationships with the Iroquois due to their proximity and trade ties. For the most part, the colonists and Iroquois had lived in relative peace since the English arrival on the continent a century and a half before. The Iroquois had to determine whether their relationships with the colonists were reliable, or whether the English would prove to better serve their interests. They also had to determine whether there were really any differences between how the English and the colonists would treat them.

The war ensued, and the Iroquois broke their confederation. Hundreds of years of precedent and collective government was trumped by the immensity of the American Revolutionary War. The Oneida and Tuscarora decided to support the colonists, while the rest of the Iroquois League (the Cayuga, Mohawk, Onondaga, and Seneca) sided with the British and Loyalists. At the conclusion of the war the fear that the colonists would not respect the Iroquois' pleas came true, especially after the majority of the Six Nations decided to side with the British and were no longer considered trustworthy by the newly independent Americans. In 1783 the Treaty of Paris was signed. While the treaty included peace agreements between all of the European nations involved in the war as well as the newborn United States, it made no provisions for the Iroquois, who were left to be treated with by the new United States government as it saw fit.[113]

Post-war

After the Revolutionary War, the ancient central fireplace of the League was re-established at Buffalo Creek. The United States and the Iroquois signed the treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784 under which the Iroquois ceded much of their historical homeland to the Americans, which was followed by another treaty in 1794 at Canandaigua which they ceded even more land to the Americans.[118] The governor of New York state, George Clinton, was constantly pressuring the Iroquois to sell their land to white settlers, and as alcoholism became a major problem in the Iroquois communities, many did sell their land in order to buy more alcohol, usually to unscrupulous agents of land companies.[119] At the same time, American settlers continued to push into the lands beyond the Ohio river, leading to a war between the Western Confederacy and the United States.[118] One of the Iroquois chiefs, Cornplanter, persuaded the remaining Iroquois in New York state to remain neutral and not to join the Western Confederacy.[118] At the same time, American policies to make the Iroquois more settled started to have some effect. Traditionally, for the Iroquois farming was woman's work and hunting was men's work; by the early 19th century, American policies to have the men farm the land and cease hunting were having effect.[120] During this time, the Iroquois living in New York state become demoralized as more of their land was sold to land speculators while alcoholism, violence, and broken families became major problems on their reservations.[120] The Oneida and the Cayuga sold almost all of their land and moved out of their traditional homelands.[120]

By 1811, Methodist and Episcopalian missionaries established missions to assist the Oneida and Onondaga in western New York. However, white settlers continued to move into the area. By 1821, a group of Oneida led by Eleazar Williams, son of a Mohawk woman, went to Wisconsin to buy land from the Menominee and Ho-Chunk and thus move their people further westward.[121] In 1838, the Holland Land Company used forged documents to cheat the Seneca of almost all of their land in western New York, but a Quaker missionary, Asher Wright, launched lawsuits that led to one of the Seneca reservations being returned in 1842 and another in 1857.[120] However, as late as the 1950s both the United States and New York governments confiscated land belonging to the Six Nations for roads, dams and reservoirs with the land being given to Cornplanter for keeping the Iroquois from joining the Western Confederacy in the 1790s being confiscated and flooded by the Kinzua Dam.[120]

Captain Joseph Brant and a group of Iroquois left New York to settle in the Province of Quebec (present-day Ontario). To partially replace the lands they had lost in the Mohawk Valley and elsewhere because of their fateful alliance with the British Crown, they were given a large land grant on the Grand River, at Six Nations of the Grand River First Nation. Brant's crossing of the river gave the original name to the area: Brant's Ford. By 1847, European settlers began to settle nearby and named the village Brantford. The original Mohawk settlement was on the south edge of the present-day Canadian city at a location still favorable for launching and landing canoes. In the 1830s many additional Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca, Cayuga, and Tuscarora relocated into the Indian Territory, the Province of Upper Canada, and Wisconsin.

In the West

Many Iroquois (mostly Mohawk) and Iroquois-descended Métis people living in Lower Canada (primarily at Kahnawake) took employment with the Montreal-based North West Company during its existence from 1779 to 1821 and became voyageurs or free traders working in the North American fur trade as far west as the Rocky Mountains. They are known to have settled in the area around Jasper's House[122] and possibly as far west as the Finlay River[123] and north as far as the Pouce Coupe and Dunvegan areas,[124] where they founded new Aboriginal communities which have persisted to the present day claiming either First Nations or Métis identity and indigenous rights. The Michel Band, Mountain Métis,[125] and Aseniwuche Winewak Nation of Canada[126] in Alberta and the Kelly Lake community in British Columbia all claim Iroquois ancestry.

The Canadian Iroquois

During the 18th century, the Catholic Canadian Iroquois living outside of Montreal reestablished ties with the League Iroquois.[127] During the American Revolution, the Canadian Iroquois declared their neutrality and refused to fight for the Crown despite the offers of Sir Guy Carleton, the governor of Quebec.[127] Many Canadian Iroquois worked for the both Hudson's Bay Company and the Northwest Company as a voyageurs in the fur trade in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[127] In the War of 1812, the Canadian Iroquois again declared their neutrality.[127] The Canadian Iroquois communities at Oka and Kahnaweke were prosperous settlements in the 19th century, supporting themselves via farming and the sale of sleds, snowshoes, boats, and baskets.[127] In 1884, about 100 Canadian Iroquois were hired by the British government to serve as river pilots and boatmen for the relief expedition for the besieged General Charles Gordon in Khartoum in the Sudan, taking the force commanded by Field Marshal Wolsely up the Nile from Cairo to Khartoum.[127] On their way back to Canada, the Canadian Iroquois river pilots and boatmen stopped in London, where they were personally thanked by Queen Victoria for their services to Queen and Country.[127] In 1886, when a bridge was being built at the St. Lawrence, a number of Iroquois men from Kahnawke were hired to help built and the Iroquois workers proved so skilled as steelwork erectors that since that time, a number of bridges and skycrapers in Canada and the United States have been built by the Iroquois steelmen.[127]

20th century

World War I

During World War I, it was Canadian policy to encourage men from the First Nations to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF), where their skills at hunting made them excellent as snipers and scouts.[128] As the Iroquois Six Nations were considered to be the most warlike of all Canada's First Nations, and in turn, the Mohawk were considered to the most warlike of all the Six Nations, the government especially encouraged the Iroquois and above all the Mohawks to join the CEF.[129] About half of the 4,000 or so First Nations men who served in the CEF were Iroquois.[130] Men from the Six Nations reservation at Brantford were encouraged to join the 114th Haldimand Battalion (also known as "Brock's Rangers) of the CEF, where two entire companies including the officers were all Iroquois. The 114th Battalion was formed in December 1915 and broken up in November 1916 to provide reinforcements for other battalions.[128] Iroquois captured by the Germans were often subjected to cruel treatment. A Mohawk from Brantford, William Forster Lickers, who enlisted in the CEF in September 1914 was captured at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, where he was savagely beaten by his captors as one German officer wanted to see if "Indians could feel pain".[131] Lickers was beaten so badly that he was left paralyzed for the rest of his life, though the officer was well pleased to establish that Indians did indeed feel pain.[131]

The Six Nations council at Brantford tended to see themselves as a sovereign nation that was allied to the Crown through the Covenant Chain going back to the 17th century and thus allied to King George V personally instead of being under the authority of Canada.[132] One Iroquois clan mother in a letter sent in August 1916 to a recruiting sergeant who refused to allow her teenage son to join the CEF under the grounds that he was underage, declared the Six Nations were not subject to the laws of Canada and he had no right to refuse her son because Canadian laws did not apply to them.[132] As she explained, the Iroquois regarded the Covenant Chain as still being in effect, meaning the Iroquois were only fighting in the war because they were allied to the Crown and were responding to an appeal for help from their ally, King George V, who had asked them to enlist in the CEF.[132]

League of Nations

The complex political environment which emerged in Canada with the Haudenosaunee grew out of the Anglo-American era of European colonization. At the end of the War of 1812, Britain shifted Indian affairs from the military to civilian control. With the creation of the Canadian Confederation in 1867, civil authority, and thus Indian affairs, passed to Canadian officials with Britain retaining control of military and security matters. At the turn of the century, the Canadian government began passing a series of Acts which were strenuously objected to by the Iroquois Confederacy. During World War I, an act attempted to conscript Six Nations men for military service. Under the Soldiers Resettlement Act, legislation was introduced to redistribute native land. Finally in 1920, an Act was proposed to force citizenship on "Indians" with or without their consent, which would then automatically remove their share of any tribal lands from tribal trust and make the land and the person subject to the laws of Canada.[133]

The Haudenosaunee hired a lawyer to defend their rights in the Supreme Court of Canada. The Supreme Court refused to take the case, declaring that the members of the Six Nations were British citizens. In effect, as Canada was at the time a division of the British government, it was not an international state, as defined by international law. In contrast, the Iroquois Confederacy had been making treaties and functioning as a state since 1643 and all of their treaties had been negotiated with Britain, not Canada.[133] As a result, a decision was made in 1921 to send a delegation to petition the King George V,[134] whereupon Canada's External Affairs division blocked issuing passports. In response, the Iroquois began issuing their own passports and sent Levi General,[133] the Cayuga Chief "Deskaheh,"[134] to England with their attorney. Winston Churchill dismissed their complaint claiming that it was within the realm of Canadian jurisdiction and referred them back to Canadian officials.

On December 4, 1922, Charles Stewart, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and Duncan Campbell Scott, Deputy Superintendent of the Canadian Department of Indian Affairs traveled to Brantford to negotiate a settlement on the issues with the Six Nations. After the meeting, the Native delegation brought the offer to the tribal council, as was customary under Haudenosaunee law. The council agreed to accept the offer, but before they could respond, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police conducted a liquor raid on the Iroquois' Grand River territory. The siege lasted three days[133] and prompted the Haudenosaunee to send Deskaheh to Washington, DC, to meet with the chargé d'affaires of the Netherlands asking the Dutch Queen to sponsor them for membership in the League of Nations.[134] Under pressure from the British, the Netherlands reluctantly refused sponsorship.[135]

Deskaheh and the tribal attorney proceeded to Geneva and attempted to gather support. "On 27 September 1923, delegates representing Estonia, Ireland, Panama and Persia signed a letter asking for communication of the Six Nations' petition to the League's assembly," but the effort was blocked.[133] Six Nations delegates traveled to the Hague and back to Geneva attempting to gain supporters and recognition,[134] while back in Canada, the government was drafting a mandate to replace the traditional Haudenosaunee Confederacy Council with one that would be elected under the auspices of the Canadian Indian Act. In an unpublicized signing on September 17, 1924, Prime Minister Mackenzie King and Governor-General Lord Byng of Vimy signed the Order in Council, which set elections on the Six Nations reserve for October 21. Only 26 ballots were cast.

The long-term effect of the Order was that the Canadian government had wrested control over the Haudenosaunee trust funds from the Iroquois Confederation and decades of litigation would follow.[133] In 1979, over 300 Indian chiefs visited London to oppose Patriation of the Canadian Constitution, fearing that their rights to be recognized in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 would be jeopardized. In 1981, hoping again to clarify that judicial responsibilities of treaties signed with Britain were not transferred to Canada, several Alberta Indian chiefs filed a petition with the British High Court of Justice. They lost the case but gained an invitation from the Canadian government to participate in the constitutional discussions which dealt with protection of treaty rights.[134]

Oka Crisis

In 1990, a long-running dispute over ownership of land at Oka, Quebec caused a violent stand-off. The Mohawk reservation at Oka had become dominated by a group called the Mohawk Warrior Society that emerged in smuggling across the U.S-Canada border and were well armed with assault rifles. On July 11, 1990, the Mohawk Warrior Society tried to stop the building of a golf course on land claimed by the Mohawk people, which led to a shoot-out between the Warrior Society and the Sûreté du Québec left a policeman dead.[136] In the resulting Oka Crisis, the Warrior Society occupied both the land that they claimed belonged to the Mohawk people and the Mercier bridge linking Montreal to the mainland.[136] On August 17, 1990, Quebec Premier Robert Bourassa asked for the Canadian Army to intervene to maintain "public safety", leading to the deployment of the Royal 22e Régiment to Oka and Montreal.[136] The stand-off ended on September 26, 1990 with a melee between the soldiers and the warriors.[136] The dispute over ownership of the land at Oka continues.

US Indian termination policies

See: Indian Termination Policy

In the period between World War II and The Sixties the US government followed a policy of Indian Termination for its Native citizens. In a series of laws, attempting to mainstream tribal people into the greater society, the government strove to end the U.S. government's recognition of tribal sovereignty, eliminate trusteeship over Indian reservations, and implement state law applicability to native persons. In general the laws were expected to create taxpaying citizens, subject to state and federal taxes as well as laws, from which Native people had previously been exempt.[137]

On August 13, 1946 the Indian Claims Commission Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 79-726, ch. 959, was passed. Its purpose was to settle for all time any outstanding grievances or claims the tribes might have against the U.S. for treaty breaches, unauthorized taking of land, dishonorable or unfair dealings, or inadequate compensation. Claims had to be filed within a five-year period, and most of the 370 complaints that were submitted[138] were filed at the approach of the five-year deadline in August 1951.[139]