Cherry Valley massacre

The Cherry Valley massacre was an attack by British and Iroquois forces on a fort and the village of Cherry Valley in central New York on November 11, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It has been described as one of the most horrific frontier massacres of the war.[1] A mixed force of Loyalists, British soldiers, Seneca and Mohawks descended on Cherry Valley, whose defenders, despite warnings, were unprepared for the attack. During the raid, the Seneca in particular targeted non-combatants, and reports state that 30 such individuals were slain, in addition to a number of armed defenders.

The raiders were under the overall command of Walter Butler, who exercised little authority over the Indigenous People on the expedition. Historian Barbara Graymont describes Butler's command of the expedition as "criminally incompetent".[2] The Seneca were angered by accusations that they had committed atrocities at the Battle of Wyoming, and the colonists' recent destruction of their forward bases of operation at Unadilla, Onaquaga, and Tioga. Butler's authority with the Indigenous People was undermined by his poor treatment of Joseph Brant, the leader of the Mohawks. Butler repeatedly maintained, against accusations that he permitted the atrocities to take place, that he was powerless to restrain the Seneca.

During the campaigns of 1778, Brant achieved an undeserved reputation for brutality. He was not present at Wyoming — although many thought he was — and he actively sought to minimize the atrocities that took place at Cherry Valley. Given that Butler was the overall commander of the expedition, there is controversy as to who actually ordered or failed to restrain the killings.[3] The massacre contributed to calls for reprisals, leading to the 1779 Sullivan Expedition which drove the Iroquois out of Western New York.

Background

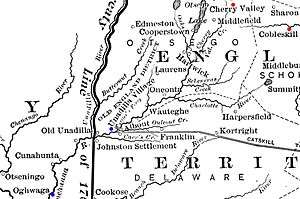

With the failure of British General John Burgoyne's campaign to the Hudson after the Battles of Saratoga in October 1777, the American Revolutionary War in upstate New York became a frontier war.[4] The Mohawk Valley was especially targeted for its fertile soil and large supply of crops farmers were supplying Patriot troops. British leaders in the Province of Quebec supported Loyalist and Native American partisan fighters with supplies and armaments.[5] During the winter of 1777–78, Joseph Brant and other British-allied Indigenous People developed plans to attack frontier settlements in New York and Pennsylvania.[6] In February 1778 Brant established a base of operations at Onaquaga (present-day Windsor, New York). He recruited a mix of Iroquois and Loyalists estimated to number between two and three hundred by the time he began his campaign in May.[7][8][9] One of his objectives was to acquire provisions for his forces and those of John Butler, who was planning operations in the Susquehanna River valley.[10]

Brant began his campaign in late May with a raid on Cobleskill, and raided other frontier communities throughout the summer.[11] The local militia and Continental Army units defending the area were ineffective against the raiders, who typically escaped from the scene of a raid before defenders arrived in force.[12] After Brant and some of Butler's Rangers attacked German Flatts in September, the Americans organized a punitive expedition that destroyed the villages of Unadilla and Onaquaga in early October.[13]

While Brant was active in the Mohawk valley, Butler descended with a large mixed force and raided the Wyoming Valley of northern Pennsylvania in early July.[14] This action complicated affairs, for the Senecas in Butler's force were accused of massacring noncombatants, and a number of Patriot militia violated their parole not long afterward, participating in a reprisal expedition against Tioga. The lurid propaganda associated with the accusations against the Seneca in particular angered them, as did the destruction of Unadilla, Onaquaga, and Tioga.[15] The Wyoming Valley attack, even though Brant was not present, fueled among his opponents the view of him as a particularly brutal opponent.[16]

Brant then joined forces with Captain Walter Butler (the son of John Butler), leading two companies of Butler's Rangers commanded by Captains John McDonell and William Caldwell for an attack on the major Schoharie Creek settlement of Cherry Valley. Butler's forces also included 300 Senecas, probably led by either Cornplanter or Sayenqueraghta, and 50 British Army soldiers from the 8th Regiment of Foot.[17][18] As the force moved toward Cherry Valley, Butler and Brant quarreled over Brant's recruitment of Loyalists. Butler was unhappy at Brant's successes in this sphere, and threatened to withhold provisions from Brant's Loyalist volunteers. Ninety of them ended up leaving the expedition, and Brant himself was on the verge of doing so when his Indigenous supporters convinced him to stay.[19] The dispute did not sit well with the Indigenous forces, and may have undermined Butler's tenuous authority over them.[17]

Massacre

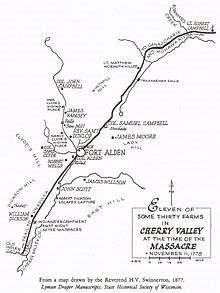

Cherry Valley had a palisaded fort (constructed after Brant's raid on Cobleskill) that surrounded the village meeting house. It was garrisoned by 300 soldiers of the 7th Massachusetts Regiment of the Continental Army commanded by Colonel Ichabod Alden. Alden and his command staff were alerted by November 8 through Oneida spies that the Butler–Brant force was moving against Cherry Valley. However, he failed to take elementary precautions, continuing to occupy a headquarters (the house of a settler named Wells) some 400 yards (370 m) from the fort.[20]

Butler's force arrived near Cherry Valley late on November 10, and established a cold camp to avoid detection. Reconnaissance of the town identified the weaknesses of Alden's arrangements, and the raiders decided to send one force against Alden's headquarters and another against the fort. Butler extracted promises from the Indigenous People in the party that they would not harm noncombatants in a council held that night.[2]

The attack began early on the morning of November 11. Some overeager Indigenous People spoiled the surprise by firing on settlers cutting wood nearby. One of them escaped, raising the alarm. Little Beard led some of the Senecas to surround the Wells house, while the main body surrounded the fort.[20] The attackers killed at least sixteen officers and troops of the quarters guards, including Alden, who was cut down while he was running from the Wells house to the fort.[21] Most accounts say Alden was within reach of the gates, only to stop and try to shoot his pursuer, who may have been Joseph Brant.[22] His wet pistol repeatedly misfired and he was killed by a thrown tomahawk hitting him in the forehead.[23] Lt. Col. William Stacy, second in command, also quartered at the Wells house, was taken prisoner.[21][23] Stacy's son Benjamin and cousin Rufus Stacy ran through a hail of bullets to reach the fort from the house; Stacy's brother-in-law Gideon Day was killed.[24] Those attacking the Wells house eventually gained entry, leading to hand-to-hand combat inside. After killing most of the soldiers stationed there, the Senecas slaughtered the entire Wells household, twelve in all.[15]

The raiders' attack on the fort was unsuccessful—lacking heavy weapons, they were unable to make any significant impressions on its stockade walls. The fort was then guarded by the Loyalists while the Indigenous People rampaged through the rest of the settlement. Not a single house was left standing, and the Senecas, seeking revenge, were reported to have slaughtered anyone they encountered. Butler and Brant attempted to restrain their actions but were unsuccessful.[15] Brant in particular was dismayed to learn that a number of families who were well known to him and whom he had counted as friends had borne the brunt of the Seneca rampage, including the Wells, Campbell, Dunlop, and Clyde families.[25]

Lt. William McKendry, a quartermaster in Colonel Alden's regiment, described the attack in his journal:

Immediately came on 442 Indians from the Five Nations, 200 Tories under the command of one Col. Butler and Capt. Brant; attacked headquarters; killed Col. Alden; took Col. Stacy prisoner; attacked Fort Alden; after three hours retreated without success of taking the fort.[26][27]

McKendry identified the fatalities of the massacre as Colonel Alden, thirteen other soldiers, and thirty civilian inhabitants. Most of the slain soldiers had been at the Wells house.[15]

Accounts surrounding the capture of Lt. Col. Stacy report that he was about to be killed, but Brant intervened. "[Brant] saved the life of Lieut. Col Stacy, who [...] was made prisoner when Col. Alden was killed. It is said Stacy was a freemason, and as such made an appeal to Brant, and was spared."[28]

Aftermath

The next morning Butler sent Brant and some rangers back into the village to complete its destruction. The raiders took 70 captives, many of them women and children. About 40 of these Butler managed to have released, but the rest were distributed among their captors' villages until they were exchanged.[29] Lt. Col. Stacy was taken to Fort Niagara as a prisoner of the British.[30]

A Mohawk chief, in justifying the action at Cherry Valley, wrote to an American officer that "you Burned our Houses, which makes us and our Brothers, the Seneca Indians angrey, so that we destroyed, men, women and Children at Chervalle."[31] The Seneca "declared they would no more be falsely accused, or fight the Enemy twice" (the latter being an indication that they would refuse quarter in the future).[31] Butler reported that "notwithstanding my utmost Precaution and Endeavours to save the Women and Children, I could not prevent some of them falling unhappy Victims to the Fury of the Savages," but also that he spent most of his time guarding the fort during the raid.[32] Quebec's Governor Frederick Haldimand was so upset at Butler's inability to control his forces that he refused to see him, writing "such indiscriminate vengeance taken even upon the treacherous and cruel enemy they are engaged against is useless and disreputable to themselves, as it is contrary to the dispositions and maxims of the King whose cause they are fighting."[33] Butler continued to insist in later writings that he was not at fault for the events of the day.[34]

The violent frontier war of 1778 brought calls for the Continental Army to take action. Cherry Valley, along with the accusations of murder of non-combatants at Wyoming, helped pave the way for the launch of the 1779 Sullivan Expedition, commissioned by commander-in-chief Major General George Washington and led by Major General John Sullivan. The expedition destroyed over 40 Iroquois villages in their homelands of central and western New York and drove the women and children into refugee camps at Fort Niagara. It failed, however, to stop the frontier war, which continued with renewed severity in 1780.[35]

Legacy

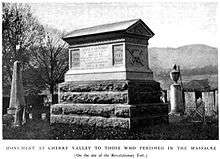

A monument was dedicated at Cherry Valley on August 15, 1878, at the centennial anniversary of the massacre. Former New York Governor Horatio Seymour delivered a dedication address at the monument to an audience of about 10,000 persons, saying:

I am here today not only to show reverence for those dead patriots, but to offer my respects and heartfelt gratitude to the living descendants of those illustrious persons of the early settlements, who have erected this memorial stone. It is to be hoped that their example will be copied; that the report of these commemorative exercises will move others to like acts of pious duty. Let every son of this soil uncover reverently as this monument is unveiled, and do reverence to their sturdy patriotism, made strong by their grand faith, their trials, and their sufferings, and show that the blood of innocent children, of wives, of sisters, of mothers, and of brave men, was not shed in vain. Let us show the world that 100 years have added to the value of that noble sacrifice. Thus we shall leave this sacred spot better men and women, with a higher and nobler purpose of life than that which animated us when we entered this domain of the dead.[36]

Years after the massacre, Benjamin Stacy's home village of New Salem, Massachusetts, celebrated the annual Old Home Day holiday with a Benjamin Stacy footrace, honoring his escape at Cherry Valley.[24]

References

- Murray, p. 64

- Graymont, p. 186

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (25 June 2013). "Atrocities, Massacres, and War Crimes: An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia". ABC-CLIO. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

Though persuaded to remain, Brantd exercised no authority over the raid (nor the regiment).

- Graymont, pp. 155–156

- Kelsay, p. 212

- Graymont, p. 160

- Barr, p. 150

- Kelsay, p. 216

- Graymont, p. 165

- Halsey, p. 207

- Graymont, pp. 165–167

- Halsey, pp. 212–220

- Barr, pp. 151–152

- Graymont, pp. 167–172

- Barr, p. 154

- Kelsay, p. 221

- Graymont, p. 184

- Kelsay, p. 229

- Kelsay, pp. 229–239

- Barr, p. 153

- Goodnough, pp. 6–9

- Sawyer and Little, p. 13

- Campbell, pp. 110–111

- Lemonds, p. 21

- Swinnerton, p. 24

- Young, pp. 449–450

- Ketchum, p. 322

- Beardsley, p. 463

- Graymont, p. 189

- Campbell, pp. 110–111, 181–182

- Graymont, p. 190

- Kelsay, pp. 231–232

- Wrong, p. 119

- Halsey, p. 249

- Barr, pp. 155–161

- "The Cherry Valley Massacre, Unveiling of the Monument to Those Who Fell on Nov. 11, 1778". The New York Times. August 16, 1878.

Bibliography

- Barr, Daniel (2006). Unconquered: the Iroquois League at War in Colonial America. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98466-3. OCLC 260132653.

- Beardsley, Levi (1852). Reminiscences; Personal and Other Incidents; Early Settlement of Otsego County. New York: Charles Vinten. p. 463. OCLC 51980748.

- Campbell, William W (1831). Annals of Tryon County; or, the Border Warfare of New-York During the Revolution. New York: J. & J. Harper. OCLC 7353443.

- Goodnough, David (1968). The Cherry Valley Massacre, November 11, 1778, The Frontier Massacre that Shocked a Young Nation. New York: Franklin Watts. OCLC 443473.

- Graymont, Barbara (1972). The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0083-6.

- Halsey, Francis Whiting (1902). The Old New York Frontier. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. OCLC 7136790.

- Kelsay, Isabel Thompson (1986). Joseph Brant, 1743–1807, Man of Two Worlds. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0208-8. OCLC 13823422.

- Ketchum, William (1864). An Authentic and Comprehensive History of Buffalo, With Some Account of Its Early Inhabitants both Savage and Civilized. Buffalo, NY: Rockwell, Baker, and Hill. p. 322. OCLC 1042383.

- Lemonds, Leo L (1993). Col. William Stacy – Revolutionary War Hero. Hastings, NE: Cornhusker Press. ISBN 9780933909090. OCLC 31208316.

- Murray, Stuart A. P (2006). Smithsonian Q & A: The American Revolution. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 9780060891138. OCLC 67393037.

- Sawyer, John; Little, Mrs. William (2007). Abstracts from History of Cherry Valley and The Story of the Massacre at Cherry Valley. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books. ISBN 1-58549-669-3.

- Swinnerton, Henry (1906). The Story of Cherry Valley. Cherry Valley, NY: New York State Historical Association.

- Wrong, George; Langton, H. H (2009) [1914]. The Chronicles of Canada: Volume IV – The Beginnings of British Canada. Tucson, AZ: Fireship Press. ISBN 978-1-934757-47-5.

- Young, Edward J (1886). Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Vol. II – Second Series, 1855–1886. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (See especially the journal of William McKendry, pp. 436–478.)

External links

- Sullivanclinton.com - historic context

- Town of Cherry Valley, Historian's website

- Photos of the Cherry Valley monument

- Cherry Valley KIA & POW

- Maine Men serving in Col. Alden's Regiment

- Finding aid to Robert Gorham Davis papers, including William McKendry’s journal, at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.