False Face Society

The False Face Society is probably the best known of the medicinal societies among the Iroquois, especially for its dramatic wooden masks. The masks are used in healing rituals which invoke the spirit of an old hunch-backed man. Those cured by the society become members. Also, echoing the significance of dreams to the Iroquois, anyone who dreams that they should be a member of the society may join.

In modern times, the masks have been a contentious subject among the Iroquois. Some Iroquois who are not members of the False Face Society have produced and sold the masks to non-Native tourists and collectors. The Iroquois leadership responded to the commercialization of this tradition and released a statement against the sale of these sacred masks. They also called for the return of the masks from collectors and museums. Iroquois traditionalists object to labeling the masks as simply "artifacts" since they are not conceived as objects but the living representation of a spirit.

Traditional Origin Story from Six Nations

As described in, for example, Fenton (1987),[1] the Creator (Shonkwaia'tison in Cayuga, lit. 'he has completed our bodies'), having just completed forming the earth and what was on it, was walking around admiring his handiwork when he noticed what appeared to be another man in the distance, walking toward him. They soon met, and Shonkwaia'tison asked the stranger where he had come from. The stranger replied, "I believe that I am the creator of this land, and I am walking around now admiring what I have done." Surprised, Shonkwaia'tison said, "No, you are wrong. It was I who created this land." They bickered back and forth like this for a little while, until finally Shonkwaia'tison said, "Fine then, let us have a test to see who actually did create this land." He pointed to a mountain in the distance. "See that mountain?" he said. "We will use our power to move it. The one who moves it the farthest must have the most power, and must therefore also be the creator of this land." The stranger agreed to this challenge, and added his own rule: "We will turn our backs," he said, "and when one's turn is up we will turn back around to see how far the mountain has moved." Shonkwaia'tison agreed to this, and so they turned.

The stranger went first. When he was satisfied that he had moved the mountain, they turned back around. Shonkwaia'tison was surprised to see that the mountain had indeed moved, although only a little bit. "Now it's my turn," Shonkwaia'tison said, and they turned their backs on the mountain once more. There was a commotion and noise behind them, and, out of curiosity, the stranger turned back around before they had agreed to it. Little did he know that Shonkwaia'tison had moved the mountain so close to the stranger's back that when he turned to look he struck his face on it. The force of the impact bent his nose and left one side of his face crooked. At this, the stranger conceded that Shonkwaia'tison was the more powerful of the two, and that he must also be the creator of the land and everything on it.

Shonkwaia'tison then had to decide what to do about the stranger. Because he had moved the mountain (if only a little bit), the stranger indeed was possessed of a certain degree of power, and Shonkwaia'tison thought that it would not do to let such a being remain on the earth; he was about to populate the earth with people, and to let this stranger coexist with them might not be a good thing. He told the stranger so, and proposed that he would have to remove him from the land. The stranger pleaded with Shonkwaia'tison and said that, if he was allowed to stay, he would help the people who Shonkwaia'tison was about to make.

"This is what I will do," the stranger said. "I have the power to control the wind, and I can protect the people in this way. If ever a strong wind or storm threatens them, I will use my cane and block it from destroying their settlements, and I can lift it and send it over their settlements so that it does not blow through. In addition to this, I have the power to heal sickness. If ever the people are struck down with illness they can call on me, and I will help them to get better. This is how they will do it. When they need aid of me in this way, they will create a mask whose face is in my image, and I will hand-pick the men who will create these masks. The very second that they lay the first strike in creating a mask, that fast will it have my power. When they use the mask they will prepare a certain kind of corn mush, and burn tobacco. The tobacco will form their words which I will hear, and I will come. They will refer to me as their grandfather, and I will help them as long as the earth remains." Shonkwaia'tison agreed to this, and allowed the stranger to stay on the earth.

Traditional Origin Story from Onondaga Nation

Iroquois oral history tells the beginning of the False Face tradition. According to the accounts, the Creator Shöñgwaia'dihsum ('our creator' in Onondaga), blessed with healing powers in response to his love of living things, encountered a stranger, referred to in Onondaga as Ethiso:da' ('our grandfather') or Hado'ih (IPA: [haduʔiʔ]), and challenged him in a competition to see who could move a mountain. Ethiso:da' managed to make the mountain quake and move but a small amount. Shöñgwaia'dihsa'ih declared that Ethiso:da' had power but not enough to move the mountain significantly. He proceeded to move the mountain, telling Ethiso:da' not to look behind him. Turning his head quickly out of curiosity, the mountain struck the stranger in the face and left his face disfigured. Shöñgwaia'dihsum then employed Ethiso:da' to protect his children from disease and sickness. But knowing the sight of Ethiso:da' was not suitable for his children's eyes, Shöñgwaia’dihsum banished him to live in caves and great wooded forests, only to leave when called upon to cure or interact through dreams. Hado'ih then became a great healer, also known as "Old Broken Nose".

False Face Tradition Today

To this day, the Iroquois believe that the being protects them in times of need, redirecting fierce winds that threaten them and healing those who are ill.

Various names are used to refer to this being among the Iroquois communities. Etihsó:t Hadú⁷i⁷ (lit. 'our grandfather, he who drives it away') is used in Cayuga. Gagöhsa' (lit. 'a face') or Sagojowéhgowa: (lit. 'he defends or protects them; the Great Defender') in Seneca. Ethiso:da' (lit. 'our grandfather') in Onondaga. In English, he is most often referred to as simply false face.

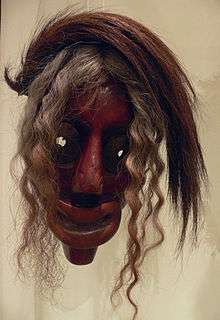

Masks

The design of the masks is somewhat variable, but most share certain features. The eyes are deep-set and accented by metal. The noses are bent and crooked. The other facial features are variable. The masks are painted red and black. Most often they have pouches of tobacco tied onto the hair above their foreheads. Basswood is usually used for the masks although other types of wood are sometimes used. Horse tail hair is used for the hair, which can be black, reddish brown, brown, grey or white. Before the introduction of horses by the Europeans, corn husks and buffalo hair were used.

When making a mask, a man walks through the woods until he is moved by Hadú⁷i⁷ to carve a mask from a tree. Hadú⁷i⁷ inspires the unique elements of the mask's design and the resulting product represents the spirit himself, imbued with his powers. The masks are carved directly on the tree and only removed when completed. Masks are painted red if they were begun in the morning or black if they were begun in the afternoon.

Because the masks are carved into trees that are alive, they are similarly considered to be living and breathing. They are served parched whitecorn mush and given small pouches of tobacco as payment for services.

Ritual

The False Face Society proper performs a ritual twice a year. The ceremony contains a telling of the False Face myth, an invocation to the spirits using tobacco, the main False Face ritual, and a doling out of mush at the end.

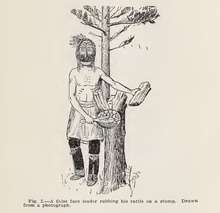

During the main part of the ritual, the False Face members, wearing masks, go through houses in the community, driving away sickness, disease and evil spirits. The False Face members use turtle shell rattles, shaking them and rubbing them along the floors and walls. The arrival of the False Faces is heralded by another medicine society that uses masks made of corn husk. If a sick person is found, a healing ritual may be performed using tobacco and singing. The tobacco is burned, and wood ashes are blown over the sick person.

The community then gathers at the longhouse where the False Faces enter and sit on the floor. The people bring tobacco which is collected as they arrive, and burned when the ceremony begins. The ceremony itself is meant to renew and restrengthen the power of the gathered masks, as well as the spirit of Hadu⁷i⁷ in general. The ritual continues with dancing. At the end of the ritual, corn mush is doled out to the assembled crowd, and everyone goes home.

The ritual is performed during the spring and fall. Other, smaller versions occur during the Midwinter Festival, and at an individual's home as requested.

Modern conflicts

The Iroquois Traditionalist Society has opposed the sale of False Face masks to private collectors and museums. The Society is very sacred and not to be shared, in any form, with those who do not belong to either the society itself or the nation, whose members are sometimes involved in the curing rites without belonging to the society. Traditionalists insist that schools should not imitate the faces for projects. It is seen as a sign of disrespect to the Iroquois people and the False Face spirit. Many Iroquois also campaign to regain possession of masks that remain with private collectors or museums. Several Iroquois governments have pushed for the return of masks to the communities from which they came. The National Museum of the American Indian in Washington D.C. has returned many items of significant importance, including masks, and is still in the process of returning others.

The Onondaga Chief Tadadaho issued a statement online in 1995 about the Haudenosaunee policies regarding masks. These policies prohibit the sale, exhibition or representation in pictures of the masks to the public. They also condemn the general distribution of information regarding the medicine societies, as well as denying non-Indigenous People any right to examine, interpret, or present the beliefs, functions, or duties of these societies.

References

- Fenton, William N. (March 1991). False Faces of the Iroquois. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806122946. Retrieved May 31, 2015.