Louis Hennepin

Father Louis Hennepin, O.F.M. baptized Antoine, (12 May 1626 – 5 December 1704) was a Belgian Roman Catholic priest and missionary of the Franciscan Recollet order (French: Récollets) and an explorer of the interior of North America.

Louis Hennepin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Antoine Hennepin 12 May 1626 |

| Died | 5 December 1704 (aged 78) |

| Occupation | Priest, Missionary |

| Organization | Franciscan Récollets |

Biography

Antoine Hennepin was born in Ath in the Spanish Netherlands (present-day Hainaut, Belgium). In 1659, while he was living in the town of Béthune, it was captured by the army of Louis XIV of France. Henri Joulet, who accompanied Hennepin and wrote his own journal of their travels, called Hennepin a Fleming (a native of Flanders), although Ath was and still is a Romance-speaking area found in present-day Wallonia. Joulet's use of the term "Fleming" here denotes a lack of understanding or generalization of this demonym, which was common at that time.[1]

Hennepin joined the Franciscans, and preached in Halles (Belgium) and in Artois. He was then put in charge of a hospital in Maestricht. He was also briefly an army chaplain.[2]

At the request of Louis XIV, the Récollets sent four missionaries to New France in May 1675, including Hennepin, accompanied by René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle. In 1676 Hennepin went to the Indian mission at Fort Frontenac, and from there to the Mohawks.[2]

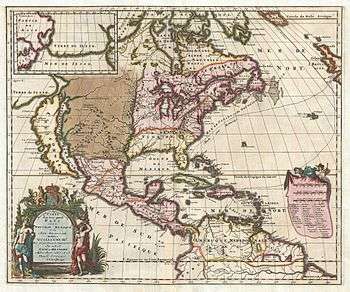

In 1678, Hennepin was ordered by his provincial superior to accompany La Salle on an expedition to explore the western part of New France. Hennepin departed in 1679 with La Salle from Quebec City to construct the 45-ton barque Le Griffon, sail through the Great Lakes, and explore the unknown West.[2]

Hennepin was with La Salle at the construction of Fort Crevecoeur (near present-day Peoria, Illinois) in January 1680. In February, La Salle sent Hennepin and two others as an advance party to search for the Mississippi River. The party followed the Illinois River to its junction with the Mississippi. Shortly thereafter, Hennepin was captured by a Sioux war party and carried off for a time into what is now the state of Minnesota.[3]

In September 1680, thanks to Daniel Greysolon, Sieur Du Lhut, Hennepin and the others were given canoes and allowed to leave, eventually returning to Quebec. Hennepin returned to France and was never allowed by his order to return to North America.[4] Local historians credit the Franciscan Récollet friar as the first European to step ashore at the site of present-day Hannibal, Missouri.[5]

Two great waterfalls were brought to the world's attention by Hennepin: Niagara Falls, with the most voluminous flow of any in North America, and the Saint Anthony Falls in what is now Minneapolis, the only natural waterfall on the Mississippi River. In 1683, he published a book about Niagara Falls called A New Discovery. The Regionalist painter Thomas Hart Benton created a mural, "Father Hennepin at Niagara Falls" for the New York Power Authority at Lewiston, New York.

Books by Hennepin

Hennepin authored:

- Description de la Louisiane (Paris, 1683),

- Nouvelle découverte d'un très grand pays situé dans l'Amérique entre le Nouveau-Mexique et la mer glaciale (Utrecht, 1697), and

- Nouveau voyage d'un pays plus grand que l'Europe (Utrecht, 1698).

- A New Discovery of a Vast Country in Voyage America (2 volumes); reprinted from the second London issue of 1698 with facsimiles of original title-pages, maps, and illustrations, and the addition of Introduction, Notes, and Index By Reuben Gold Thwaites. A.C. McMlurg & Co., Chicago, 1903.

The truth of much of Hennepin's accounts has been called into question — or flatly denied — notably by American historian Francis Parkman, himself also cited for cultural bias, including against both French and Native Americans.

Hennepin has been denounced by many historians and historical critics as an arrant falsifier. Certain writers have sought to repel this charge by claiming that the erroneous statements are in fact interpolations by other persons. The weight of the evidence is however adverse to such a theory.

— Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913

Legacy

Places named after Hennepin are found in the United States and Canada:

Illinois:

- The city of Hennepin, Illinois

- Hennepin Room at Starved Rock Lodge and Conference Centre in Utica, Illinois

- The Hennepin Canal

Michigan:

- Point Hennepin, the northern tip of Grosse Ile, an island on the Detroit River south of Detroit

- Hennepin Street in Garden City, Michigan

- Hennepin Road in Marquette, Michigan

- Hennepin, significant as the first self-unloading bulk carrier.[6] Wreckage is located west of South Haven, Michigan.

Minnesota:

- Hennepin County, Minnesota, whose seat is Minneapolis

- Hennepin Avenue, in Minneapolis

- The Father Louis Hennepin Bridge, across the Mississippi River in Minneapolis

- Father Hennepin State Park, in Isle, Minnesota

- A Great Lakes wood-hulled steamer built in 1888 which sank in 1927[7]

- The city of Champlin, Minnesota, the site historians report where he first crossed the Mississippi in 1680, holds an annual Father Hennepin Festival on the 2nd weekend of June that includes a reenactment of Father Louis Hennepin crossing the Mississippi River.

- Hennepin Island is in the Mississippi River at St. Anthony Falls. Although it is no longer an island, it extends into the river and houses the Saint Anthony Falls Laboratory at the University of Minnesota, a five-unit hydroelectric plant, owned by Xcel Energy, and the Main Street substation – serving downtown Minneapolis.

- Father Hennepin Park lies on the east bank of the Mississippi River adjacent to Hennepin Island. It is administered by the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board and features picnic areas, a bandshell, and Heritage Trail plaques.

- Hennepin Room at the Minneapolis Hilton Hotel

- The Father Hennepin Memorial stands on the grounds of Saint Mary's Basilica in Minneapolis.[8]

New York:

- Hennepin Road in Grand Island, New York

- Hennepin Avenue on Cayuga Island in Niagara Falls, New York

- Hennepin Room at the Niagara Falls Conference Center in Niagara Falls

- Hennepin Park, a park located on the corner of 82nd Street and Bollier Avenue in Niagara Falls

- Hennepin Hall, a residence hall at Siena College, Loudonville, New York

- Hennepin Park, a park located in the East Lovejoy neighborhood of Buffalo, New York

- Hennepin Parkway, also known as Hennepin Street, a street on the north side of Hennepin Park in the East Lovejoy neighborhood of Buffalo

- Hennepin Farmhouse Saison Ale (beer) from Brewery Ommegang in Cooperstown, New York

Niagara Falls, Ontario:

- Father Hennepin Separate School

- Ontario Historical Plaque at Murray Avenue and Niagara River Parkway

- Hennepin Room at Niagara Falls Marriott on the Falls Hotel

- Hennepin Crescent

Pop culture references to Hennepin

The final track on the 2006 album 13 by Brian Setzer is entitled "The Hennepin Avenue Bridge." Its lyrics tell a fictitious story of Fr. Hennepin and his leap from the Hennepin Avenue Bridge over the Mississippi River.

References

- Profile, archive.org; accessed 20 November 2015.

- Corrigan, Michael. "Register of the Clergy Laboring in the Archdiocese of New York", Historical Records and Studies, Vol. 1, United States Catholic Historical Society, 1899 p. 34

- Shea, John Gilmary. DESCRIPTION of LOUISIANA, By FATHER LOUIS HENNEPIN, RECOLLECT MISSIONARY: Translated from the Edition of 1683, and compared with the Novella Decouverte, The La Salle Documents and other Contemporaneous Papers, New York: John G Shea (1880), pp 368–70. (The spelling Recollect is the translator's. See original title page (image at Hathi Trust).)

- Profile, Dictionary of Canadian Biography (online)]; accessed 20 November 2015.

- National Geographic Magazine, July 1956, Vol CX, No. 1, pp 135–36.

- Valerie Olson van Heest, writer and director (2007). She Died a Hard Death: The Sinking of the Hennepin (DVD). Michigan Shipwreck Research Associates. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Jitka, Hanáková. "Hennepin". Shipwreck Explorers. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- http://www.mary.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=101&Itemid=227

External links

- Louis Hennepin in MNopedia, the Minnesota Encyclopedia

- Full text of Nouvelle découverte d'un très grand pays situé dans l'Amérique entre le Nouveau-Mexique et la mer glaciale, from the Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Full text of Nouveau voyage d'un païs plus grand que l'Europe, from the Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Article on Louis Hennepin profile in the Catholic Encyclopedia.