Shasta people

The Shastan peoples are a group of linguistically related indigenous peoples from the Klamath Mountains. They traditionally inhabited portions of several regional waterways, including the Klamath, Salmon, Sacramento and McCloud rivers. Shastan lands presently form portions of the Siskiyou, Klamath and Jackson counties. Scholars have generally divided the Shastan peoples into four languages, although arguments in favor of more or less existing have been made. Speakers of Shasta proper-Kahosadi, Konomihu, Okwanuchu, and Tlohomtah’hoi "New River" Shasta resided in settlements typically near a water source. Their villages often had only either one or two families. Larger villages had more families and additional buildings utilised by the community.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 653 [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

( |

The California Gold Rush drew in an influx of outsiders into California in the late 1840s eager to gain mineral wealth. For the Shasta, this was a devastating process as their lands soon had thousands of miners operating along various waterways. Conflicts arose as the outsiders didn't respect the Shasta or their homeland. Introduction to new diseases and fighting against invading Americans rapidly reduced the number of Shasta. The Shasta residents of Bear Creek were active in Rogue River Wars and assisted the Takelma until they were forcibly removed to the Grande Ronde and Siletz Reservations in Oregon. In the late 1850s the Shastan peoples of California were forcibly removed from their territories and also sent to the same two distant reservations.[2] By the early years of the 20th century perhaps only 100 Shasta individual existed.[3] Some Shasta descendants still reside at the Grand Ronde and Siletz Reservations, while others are in Siskiyou county at the Quartz Valley Indian Reservation or Yreka. Many former members of the Shasta tribe have also been inducted into the Karuk and Alturas tribes.

Origin of name

Prior to contact with European descendants the term Shasta likely wasn't used by the Shastan peoples themselves. Among the Shasta proper they called themselves "Kahosadi" or "plain speakers".[4] Variations of Shasta used by whites include Chasta, Shasty, Tsashtl, Sasti, and Saste.[3][5] Dixon noted that the Shastan peoples didn't use "Shasta" as a place name and likely wasn't a word at all in their languages. In interviews with Shasta informants Dixon was informed of a prominent man of Scott Valley that lived up until the 1850s with the name of Susti or Sustika. This was the probable origin of the term according to Dixon,[6] an interpretation that Kroeber agreed with.[3] Merriam reviewed information from Albert Samuel Gatschet and fur trader Peter Skene Ogden, concluding that while the Shastan peoples didn't refer to themselves as Shasta traditionally; the nearby Klamath likely did.[7] Scholars have largely accepted Dixon's etymology for Shasta. Renfro questions its validity however as Ogden used a variation of the term before Sustika was likely prominent.[8]

In 1814, near the Willamette Trading Post a meeting occurred between North West Company officer Alexander Henry and an assembled Sahaptin congregation of Cayuse and Walla Walla, in addition to a third group of people that was named Shatasla. Maloney argued that Shatasla was an archaic variant of Shasta.[9] something Garth later conjectured as well.[10] This interpretation has been contested by other scholars based on linguistic and historical evidence. Previous to Maloney's assertion, Frederick Hodge in 1910 noted the word Shatalsa as being related to word Sahaptin.[11] This older etymology was defended by Stern against Maloney's interpretation,[12] in addition to recently being accepted by Clark as well.[13]

Social organization

The Shasta were the numerically largest of the Shastan speakers. Their territories spread from around modern Ashland in the north, Jenny Creek and Mt. Shasta to the east, southward to the Scott Mountains, and westward to modern Seiad Valley and the Salmon and Marble Mountains.[14] This area had four important waterways, each of which had a distinct group of resident Shasta. These were the Klamath River and two of its tributaries, the Shasta River and Scott River, along with the Bear Creek in the Rogue Valley. Four bands of Shasta existed with variations in custom and differing dialects. Each band had names derived from nearby waterways. In this way people from Shasta River or Ahotidae were the "Ahotireitsu", those from the Upper Rogue Valley or Ikiruk were the "Ikirukatsu", and inhabitants of Scott River or Iraui were the "Irauitsu".[4][2] Shasta families located directly along the Klamath River were referred to by the Ikirukatsu as "Wasudigwatsu" after their particular words for the Klamath River and gulch. The Irauistu knew them as "Wiruwhikwatsu" and the Ahotireitsu called them "Wiruwhitsu", terms derived from "down river" and "up river" respectively.[4][2]

Shasta settlements often only contained a single family. In larger villages headmen held sway. The responsibilities of this position were varied. They were expected "to exhort the people to live in peace, do good, have kind hearts, and be industrious."[14] A common requirement to hold the position was that the individual had to be materially wealthy. This came from the expectation for them to use their property in negotiations to settles disputes between members of their village or with other settlements.[15] In raids on enemies the headman did not participate but negotiated with enemy headmen to establish peaceable relations. Each of the four Shasta bands had individual headmen as well.[15] While only the Ikirukatsu were reported to have had hereditary succession to the position it is thought the other three bands had some form hereditarian succession as well. While each of the four band headmen were considered equal, in particularly trying disputes the Ikirukatsu headman would negotiate an end to the issue.[16]

Affiliated peoples

Three related groups of Shastan speakers resided adjacent to the Shasta proper. These were the Okwanuchu of the upper Sacramento and McCloud rivers, and the Salmon River based Konomihu and Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta. There is little recorded information on the Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta, Konomihu and Okwanuchu. Merriam concluded that "any extended discussion of their culture, customs, beliefs, and ceremonies is out of the question..."[17] Each group had particularly small territories. The Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta held 45 square miles (120 km2), the Okwanuchu had 60 square miles (160 km2), and the Konomihu only occupied 20 square miles (52 km2).[17]

The Shasta called the Konomihu "Iwáppi", related to the term used for the Karuk. The Konomihu referred to themselves as "Ḱunummíhiwu".[18] They inhabited portions of the north and south forks of the Salmon River, in addition to part of the combined waterway. Seventeen settlements are recorded to have existed within Konomihu territory.[17] Political authority was more fragmented than the Shasta, reportedly there being no form of appointed or hereditary village headmen.[17] Most knowledge of Konomihu interactions with neighboring peoples has been lost. It is known that despite occasional disputes with the Irauitsu Shasta,[18] intermarriage was common.[19] The Irauitsu appear to have been important trading partners as well. In return for their buckskin garments the Konomihu received abalone beads.[19]

It is not known what the autonym of the Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta was. However it is known that the Shasta likely referred to them as "tax·a·ʔáycu", the Hupa called them "Yɨdahčɨn" or "those from upcountry (away from the stream)", while the Karok called them "Kà·sahʔára·ra" or "person of ka·sah".[18] The Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta largely lived in the Salmon River basin despite the scholarly appellation, though they did reside on the forks of the New River. There were at least five reported settlements inhabited by Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta according to information gained from particular informants.[20] Residents of the New River forks were proposed by Merriam to speak a distinct language from the Salmon River inhabitants.[20] Dixon criticized the idea and presented evidence for the linguistic unity of the cultural group.[21] Merriam's conclusion of there being two differing languages between the Tlohomtah’hoi Shasta group has not been adopted by other scholars.[18]

What information has been preserved about the Okwanuchu amounts to little. The origin of the word Okwanuchu is unknown. They were called "ye·tatwa"[22] and "Ikusadewi"[23] by the Achomawi. Intermarriage between Okwanuchu and Achomawi speakers was apparently common.[22]

Population

Estimates for historic Shasta, Okwanuchu, New River Shasta, and Konomihu population figures have substantially varied, as is true for most native groups in California. In the 1990s some Shasta stated upwards of 10,000 Shastan peoples lived in the 1840s.[24] Alfred L. Kroeber put the 1770 population of the Shasta proper as 2,000 and the New River, Konomihu, and Okwanuchu groups, along with the Chimariko, as 1,000.[23] Using population information on a nearby culture, Sherburne F. Cook largely agreed with Kroeber and concluded there were about 2,210 Shasta proper and another 1,000 related peoples.[25] Subsequently, however Cook raised the figure to 5,900 total Shasta, inclusive of the smaller related cultures.[26] Kroeber estimated the population of the Shasta proper in 1910 as 100.[3]

Historic culture

Diet

.jpg)

The Shastan peoples had a diet based around locally available food sources. Many plant and animal species that existed in Shasta territories were located in adjacent areas. These food sources were commonly gathered and used by the Shasta and other regional cultures. The large populations of game animals in the Shasta territories led to many confrontation from other California Natives keen on gaining animal meat and pelts. Strategies to procure and later store these foodstuffs shared similarities with adjoining cultures.[27] Undergrowth in forests was removed with controlled fires to promote advantageous plant species that were often food sources.[28]

Fishing runs began in the spring and continued throughout the summer and autumn. The White Deerskin dance by the Karuk determined the appropriate time for the Shasta to eat fish. Held sometime in July, the dance was an important event for Shasta to witness and known as "kuwarik".[29] Prior to the event Coho salmon could be caught and dried, but not consumed. Rainbow trout had to be released before the Karuk dance. Not doing so was seen as particularly egregious and made one liable to be killed.[29] Spears were reportedly uncommon for use in fishing among the Shasta. Fires were created and maintained at weirs to enable efficient night fishing. Fishing nets designs were near identical to those created by Karuk and Yurok. Catfish and crawfish were caught with bait tied to lines. Once stuck on the line, the prey would be captured with a thin basket.[29]

California mule deer were hunted according to one of several strategies employed by the Shasta.[30] In the autumn at mineral licks deer were forced by controlled burning of oak leaves into gaps between the flames where hunters would wait.[31] Shasta also chased deer into nooses that were tied to trees. Alternatively dogs were trained to chase deer into creeks. Hidden until their prey was in the water, Shasta hunters would then kill the deer with arrows.[30] There were a number of societal conventions related to the ownership of the deer. For example, whoever killed the prey had right to its pelt and hind legs. Other reported conventions regulated the divisions of meat in a fair manner and when Shasta were allowed to hunt.[30]

.jpg)

Additional nutritional sources included several smaller animal species. Mussels were collected from the Klamath River by women and children that dived for the organisms. During the autumn the river shrunk in size, leaving exposed populations of mussels along the river banks. Once gathered in a sufficient quantity the mussels steamed in earthen ovens. Then the shells were opened and the meat dried through sunlight for future use.[32] Grasshoppers and crickets were consumed by both the Ahotireitsu and Ikirukatsu Shasta. Parcels of grasslands were set ablaze by Shasta men. After the fires had died down the cooked grasshoppers were collected and dried. When grasshoppers were served with particular grass seeds the insects were pounded into a fine powder.[32] Visitors to Shasta Valley would join Ahotireitsu during periods of abundant insect populations to collect their own food stores.[33]

Acorns were a valuable foodstuff in Shasta cuisine. Local sources of the nut included the Canyon Oak, California Black Oak and the Oregon White Oak.[27] After leeching the acorns of tannins the nuts were turned into a dough. Black Oak meal was preferred compared to the slimier and less popular White Oak meal for both consumption and trade. Canyon Oak acorns were often buried and allowed to turn black before being cooked.[27] Often nuts from Sugar pines were steamed, dried and stored for future consumption.[27] Pitch from the Ponderosa pine was pounded into a fine dust and consumed or used as a chewing gum.[34] Many fruits were harvested once ripe and often dried. This included Chokecherries, Whiteleaf manzanita berries, Pacific blackberries, San Diego raspberries, and Blue elderberries.[35]

Flower bulbs were gathered seasonally to supplement other food stores. Camas roots were commonly collected. Members of the calochortus genus were known as "ipos" to the Shasta who relished them.[32] Once the bulb was husked ipos roots were consumed raw or dried in sunlight and later stored. Shastan cuisine had many meals that included dried ipos. Guests were often given small servings of serviceberries and dried ipos while the main meal cooked. One particularly popular dish was powdered ipos root mixed into manzanita cider.[32] Another consumed flowering plant species was Fritillaria recurva. Commonly called "chwau", the bulbs were prepared by either roasting or boiling.[32]

Housing

Shasta architecture appears to have large been derived from the downriver Hupa, Karuk and Yurok peoples.[36] Permanent houses were constructed by the Shasta for the winter. These dwellings were built in the same locations annually, commonly near a creek. Klamath River Shasta winter villages commonly had only 3 families, while Dixon has suggested that both Irauitsu and Ahotireitsu villages usually had more families.[36] The beginning of a winter house started with excavating a pit. Common dimensions rectangular or oval shaped excavation were 16.3 feet (5.0 m) by 19.8 feet (6.0 m), with a depth of 3.3 feet (1.0 m). Once the area was cleared load bearing wooden poles were placed in the excavated corners. Additional wooden supports and posts placed throughout the structure. After the pit walls were covered with cedar-bark, the sugar-pine or cedar wooden roof was finally put into place.[36]

The okwá'ŭmma ("big house")[36] was a structure maintained in populous Shasta villages. A pit up to 26.3 feet (8.0 m) wide, 39 feet (12 m) wide and 6.6 feet (2.0 m) deep was dug, with a building process similar to winter dwellings employed. Their functionality was primarily for assemblies, such as seasonal religious ceremonies and dances. Dixon incorrectly reported that okwá'ŭmma were used as sweat houses.[37] If a villager had too many guests for their house, permission would be secured to use the okwá'ŭmma instead. Okwá'ŭmma were owned by a prominent individual, often the headman, and constructed with communal labor.[36] They were uncommon buildings, as along the Klamath River perhaps only three existed. Male relatives of the owner inherited the structure, if only female relatives remained it was burnt down.[37]

Dwellings utilized by the Konomihu varied according to season like the Shasta. During the salmon runs of spring and summer huts created from plant brush were used. These were abandoned in the autumn in favor of bark houses while deer were hunted.[18] These winter houses were markedly different from the Shasta, Karuk and Yurok.[19] While partially underground their houses were built in 15 to 18 foot wide circles with sloped conical roofs.[17]

Manufactured items

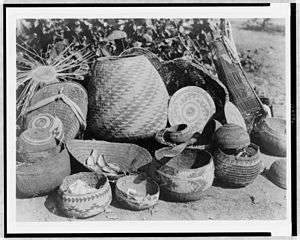

An important item for Shasta households were baskets which principally came from the Karuk. The Konomihu likewise largely imported their baskets from abroad.[19] Baskets made by Shasta were generally a composite of plant materials gathered from the Ponderosa pine, California hazelnut, several species of Willow, Bear grass, and the Five-fingered fern. Their designs took influences from the nearby Hupa, Karuk and Yurok peoples.[38] Pigments were made by the Shasta for the beautification of baskets and other personal possessions. Red and black dyes were the most commonly used and come from acorns and alder bark respectively.

Ropes, cordage and manufactured goods such as mats, nets and clothing were largely derived from Indian hemp.[39] During the winter snow shoes were often necessary to traverse their homeland. These were made primarily from deer hide with the fur left on.[40] Dentalium shells were an important possession for the Shasta. Principally they were used for ornamentation through being sown into clothing, in addition to usage as a bartering medium.[39] Konomihu produced buckskin leggings, robes and skirts that were painted with black, red and white patterns and adorned with dentalia and abalone beads.[19] Okwanuchu crafted tubular wooden pipes similar in design to those made by Wintu.[41] Raccoon and fox pelts were used for protection against the harsh mountain winters. Moccasins were kept waterproof and soft with oils derived from either deer, fish, cougars or bears.[42]

Charles Wilkes described Shasta made weaponry in 1845:

"Their bows and arrows are beautifully made: the former are of yew and about three feet long; they are flat, and an inch and a half to two inches wide: these are backed very neatly with sinew, and painted. The arrows are upwards of thirty inches long; some of them were made of a close-grained wood, a species of spiraea, while others were of reed; they were feathered for a length of from five to eight inches, and the barbed heads were beautifully wrought from obsidian... Their quivers are made of deer, raccoon, or wild-cat skin; these skins are generally whole, being left open at the tail end."[43]

Body modification

Body decoration and modification were common practices among the Shasta. For example, they employed dyes of red, yellow, blue, black and white in their artwork. These dyes were created from plant matter and natural clay deposits. Reportedly body painting was largely used by shamans and those preparing for warfare. The latter group generally used white and black colors during their war preparations. Red was applied by shamans upon their buckskins in geometric patterns.[38]

Permanent tattooing was performed by elder women who used small obsidian flakes. Tattoos for women were generally several vertical marks on the chin that occasionally were prolonged to the edges of the mouth. Women without chin tattoos were seen as unattractive and targets of ridicule.[44] For men tattoos had an important functionality in bartering and exchanges. Applied in lines on their hands or arms, these lines were used to measure dentalia and beads. Septum piercings were made to hold either a long dentalia shell or ornate feathers, while ear piercings held an assembled group of dentalia.[40]

Warfare

Warfare was principally performed in asymmetrical small raids. Leaders of these attacks were determined by raiding party members. An armed group was organized usually to redress aggression and violence against village members.[45] Prisoners gained in raids were not often killed and instead were allowed to live as a slave.[46] Slavery was reportedly not widespread among the Shasta and wasn't seen as a favorable practice. Dixon stated that "persons owning slaves were said to be, in a way, looked down upon."[47]

Shasta warriors wore protective adornments when headed into a conflict. Stick armor was preferred over the alternative elkhide. Materials for stick armor were largely sourced from serviceberry trees and woven together tightly with twine.[46] As a rule head coverings were made from elk hide, sometimes placed in several layers thick. Notably Shasta women could join in both preparations for an upcoming attack and as active participants in the battle itself. Dixon recorded in such instances women would be armed with obsidian knives and attempt to disarm or destroy the weapons of enemy combatants.[46]

Armed warriors came largely from the Klamath River and Ahotireitsu Shasta in conflicts with the Modoc. These clashes have been speculated to have been the most violent for the Shasta by scholars. While disputes and raids occurred with the Wintu, they were apparently not as destructive as warfare with the Modoc.[48] Attacks on Wintu and Modoc villages included torching the settlement. This was not practiced in raids between Shasta villages.[48]

Neighboring societies

.jpg)

The Shasta were located at the crossroads of several major cultural regions.[24] This was reflected in their neighbors, each with distinct material and cultural conditions. To the southwest on the lower Klamath River were the Karuk, Yurok and Hupa. Past the southern borders of Shasta territory resided the Wintu. They were the northernmost extension of a central Californian culture focused on the Russian River Pomo and the Patwin.[49] To the east and southeast were the Achomawi and Atsugewi, with whom the Shasta have some linguistic affiliations. Kroeber placed the Achomawi and Atsugewi with the northeastern Modoc and Klamath into the "Northeast" cultural group.[50] They received cultural influences from the Columbia Plateau and Columbia River Sahaptins, far more than the Shasta did.[3]

Klamath River societies

Coming from the Shasta word for "down the river" the Karuk were known as "Iwampi".[4] Along with the Yurok, both nations inspired many facets of Shasta society and were their principal trading partners.[51] These peoples were particularly similar to the Shasta and these ethnicities formed the southern terminus "of that great and distinctive culture [...] common to all peoples of the Pacific coast from Oregon to Alaska."[52] Additional members of this grouping included the Tolowa further to the west and the Takelma located to the north.[49]

The Karuk culture was held in a favorable regard by most Shasta, particularly for their manufactured items.[4] Shasta merchants would bring stockpiles of trade goods in demand down river, which included a variety of preserved foodstuffs, animal pelts, and obsidian blades. Merchandise found desirable by the Shasta included Tan Oak acorns, Yurok produced redwood canoes, a gamut of baskets of varying designs, seaweed, dentalia and abalone beads.[53][51][3] The Karuk also were the primary source of dentalia for the Konomihu as well.[19] Baskets and hats used by the Shasta were acquired primarily with these Klamath River nations.[54]

Takelma

The delimitation of territory with the Takelma to the north has been a matter of controversy between scholars. Shasta informants told Roland B. Dixon that they previously occupied the Bear Creek Valley southward and eastward of the Table Rocks. He was additionally given Shasta place names of this area. This information was forwarded to Edward Sapir who suggested that the Shasta and Takelma both utilized this disputed region of the Rogue Valley.[55] Alfred Kroeber would in turn claim that Shasta territories extended as far north as modern Trail, Oregon.[3]

Based on a review on accounts by Takelma and Shasta informants and the journal of Ogden, Gray has determined and proposed a revised cultural boundary. During the early 19th century the southern Bear Creek valley was used by both the Shasta and Takelma peoples as Sapir had speculated. The higher portions of the local Neil and Emigrant Creeks, in addition to the northern Siskiyou slopes close to Siskiyou Summit were Shasta areas.[56] Regardless of their conflicts over the Bear Creek Valley, the Takelma were active trading partners with the Shasta and were a major source of dentalia.[51]

Lutuamian peoples

Known as the "Ipaxanai" from the Shasta word for "lake", the Modoc were traditionally held in low regard and were seen as without much material wealth by the Shasta. For example, a Shasta informant reported that "How could you settle anything with them? They didn't have any money."[4] There was an amount of commercial transactions between the Shasta and the Klamath but these were apparently rare occurrences.[51] Spier reported that Shasta manufactured beads were exchanged for animal pelts and blankets.[57] Outside of trading with the Modoc, this was some of the only trading done between the Klamath and the Indigenous peoples of California.[58] Both the Modoc and their Klamath relatives gained horses in the 1820s.[59] This greatly enhanced their military capabilities which began a period of attacks on their southern and western neighbors. Both the Ahotireitsu and Klamath River Shasta bands were targets of Modoc slave raiding.

Achomawi & Atsugewi

The Achomawi and Atsugewi speakers resided to the east in the Pit River basin. Not much has been recorded on interactions the Shasta had with them. It is known that the Shasta were the principal source of dentalia for both peoples.[60] There was some direct contact with the Atsugewi though it was probably minimal.[61] Atsugewi informants agreed that they traditionally had many shared cultural traits with the Shasta especially their similar "religion, mythology, social organization, political organization, puberty customs, and paucity of ceremonial."[62] The Madhesi band of Achomawi were known to have had occasional disputes. Villages in the vicinity of modern Big Bend were liable to be raided by Shasta warriors.[63]

Wintu

Bands of Wintu located around modern McCloud, California and in the Upper Sacramento Valley had the majority of interactions with the Shasta.[64] While clashes did occur with Wintu speakers, it wasn't nearly as common as conflict with the Modoc.[48] These conflicts earned the Shasta the Wintun name of "yuki" or "enemy".[64] Despite the occasional skirmish there was some commercial and cultural exchanges between the peoples. The Wintu were an active source of Tan oak acorns and abalone beads.[51] The Shasta were the primary distributors of dentalia to the Wintu, along with some obsidian and buckskin.[65] A drink made by both the Shasta and the Wintu was a cider created from Manzanita berries.[27] Members of both cultures were inspired by the manufactured goods created by the other nation. Ahotireitsu Shasta considered clothing made by Wintu fashionable and made hats from Indian hemp after their style.[39] Upper Sacramento Valley and McCloud Wintu admired the smooth headgear used by the Shasta. These twine hats were copied by the Wintu, who used material from Woodwardia ferns in their reproductions more often than among their own designs.[66]

Early nineteenth century

Originating from the Chinook Jargon word for an American, "Boston," the Shasta word for whites is "pastin."[67] The Shasta were isolated from the Spanish to the south and their Californian colonies. When the Mexican War of Independence erupted Mexican officials assumed control of the Spanish settlements and missions by forming the Alta California territory. This didn't change matters for the natives north of the Californian Ranchos as they maintained their territorial autonomy and protected position against European descendants. Sometime around the 1820s the Modoc and Klamath adopted horses from the Sahaptin peoples to the north. With their new equestrian rides they began to attack the Shasta, Achomawi and Atsugewi for property, food stores and slaves to be sold at the Dalles.[59] The Shasta actively fought against the invaders although they didn't gain sizable numbers of horses.

The first recorded encounter with European descendants for the Shasta came in 1826. A Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) expedition under Peter Skene Ogden departed from Fort Vancouver to trap beavers in the Klamath Mountains. Arriving from the east, Ogden's party was favorably received by Shasta. Ogden was disappointed by the small number of beaver in the mountainous region and shifted the party north to the Rogue Valley across the Siskiyous. Shasta guides accompanied them until shortly before modern Talent.[56] The HBC continued to send expeditions southward through the Klamath Mountains to harvest beaver populations in Alta California. These groups of fur trappers and their families traveled along the Siskiyou Trail which traversed portions of the Shasta homelands.

The following known interaction with whites wasn't peaceable as Ogden's visit had been. A group of Willamette Valley colonists traversed Shasta territories in the autumn of 1837. With them were several hundred cattle purchased from Alta California Governor Alvarado. Driving their herd north along the Siskiyou Trail,[68] they encountered several Shasta settlements. The Shasta were welcoming to the outsiders despite difficulties in communication. Philip Leget Edwards recorded that the cattle drivers were "at their mercy, but they have offered no injury to ourselves or property."[69] A Shasta boy estimated by Edwards to be the age of ten accompanied the settlers for some time. As the group continued north some of the cattle men began to discuss killing natives of the area. William J. Bailey and George K. Gay had previously had fought against a group of Takelma of the Rogue Valley, getting injured and losing several companions. They considered the Shasta to be acceptable targets to attack for revenge.[70] A Shasta man was found and shot to death by Gay and Bailey. They also attempted to murder the Shasta youth that had joined the cattle herders but he escaped. While officer Ewing Young was furious at the murder, the majority of the party condoned the murder.[70] Bailey and Gay faced no punishment for their actions and the party continued toward the Willamette Valley.

Several years later a portion of the United States Exploring Expedition under the command of Lieutenant George F. Emmons (1838-1842) visited the Klamath Mountains. Emmons had been given instructions by Charles Wilkes to explore the headwaters of the Klamath, Sacramento, and Umpqua rivers.[71] The assembled men had departed from Fort Vancouver to Fort Umpqua during the summer of 1841. During September and October they traveled through Shasta territories by generally following the Siskiyou Trail.[72] On 1 October the party crossed the Klamath River. The explorers visited a Shasta village where inhabitants gave them salmon and sold several yew bows and arrows in exchange for trade goods.[73] Inhabitants of the village demonstrated their archery skills by repeatedly shooting a button from 20 yards (18 m) distant.[72] At this demonstration was an elder Shasta man who was a father-in-law to Michel Laframboise.[74] Shortly after this peaceable dialogue and trade Emmons ordered the party to depart for "Destruction river" (the Upper Sacramento River)[75] exiting Shasta lands for those of the Okwanuchu and later the Wintu.[74]

Discovery of gold

The irregular contact with European descendants became far more frequent by the 1840s. Military forces of the United States conquered Alta California during the Mexican–American War. American control was initially limited to areas that had been administered by the Mexican government. The California Territory was established in 1849 although much of the claimed land still remained in indigenous hands. The California State Legislature organized Shasta County in 1850. Once it was firmly in control by American colonists it was speculated to become an important region for its agricultural and mineral potential.[76] In 1852 Siskiyou County was formed from the northern portions of Shasta County. This new American division contained the Shasta homelands of California.

The lure of achieving material wealth created the California Gold Rush and drew in outsiders by the hundreds of thousands. The newly arriving miners and colonists had little respect for California Natives and frequently spread violence against indigenous peoples. Miners progressively went north from Sutter's Mill in search of more gold. During 1850 discoveries of gold were made on the Trinity and Klamath rivers. In the Shasta heartland along the banks of the Salmon, Scott and upper Klamath gold was found during the following two years. Incoming miners founded the towns of Scott Bar and Yreka near these newer sources.[77] The Shasta weren't seen favorably by incoming miners, being considered to have "inherited a spirit of warfare, and delight in [...] perilous incidents of daring thefts or bold fighting.[78] This image of native aggression was repeatedly mentioned in contemporary newspapers. The Shasta and other natives in the north were apparently found to be "more warlike than those of any other section of the State, and bear the most implacable hatred towards all pale faces."[79]

By August 1850 there were over 2,000 miners prospecting on Klamath and Salmon rivers. Over a hundred miles of the Klamath River had been searched for gold deposits and portions were occupied by mining operations. While the Shasta River hadn't yet been exploited it was considered by miners to contain rich gold deposits.[80] In the winter of 1850 advertisements appeared in the Daily Alta California promoting the mineral potential of the Klamath River basin. These notices appealed for Americans to venture north where opportunities for acquiring wealth abound.[81] In addition to maintaining extensive mining operations, whites began to cut forests down for sale in Sacramento.[82] A thousand acres of Shasta river had been prospected to varying amounts by April 1851.[83] Scott River became touted as having "the richest mines in all California."[84] Contemporaries described an influx of miners into the northern region. "The tide of emigration to Scott's River [...] flows due north, sweeping everything in its way..."[85] Redick McKee visited the Scott River in October 1851. He reported that "squatter' tents and cabins may be seen on almost every little patch or strip where the soil promises a reward to cultivation."[86] Additionally he noted the Scott River was under heavy modification by miners. "Every yard almost for three or four miles is either dam or race work."[87]

As the population of non-natives rose in the north genocide of the indigenous was considered. Miners argued that natives along the Klamath River and its tributaries impeded access to gold deposits. They were deemed "the only obstacle to complete success in those mines."[88] The Sacramento Daily Union argued that "the Indians must soon be removed by the Government Agents, or be exterminated by the sword of the whites."[89] Violence and murder against natives were often promoted as the only way to end their "thieving and other annoying propensities."[90] Violence began to erupt across the Klamath River in the summer of 1850. In August it was reported that miners had killed fifty to sixty Hupa and burnt down three of their villages around the juncture of the Klamath and Trinity rivers.[90] At the junction of the Shasta and Klamath rivers in October a confrontation erupted in which miners killed six Shasta.[91]

Federal peace effort

The Indian Superintendency gave a report to Congress in November 1848. It was an overview on native population figures in the recently gained Pacific Coast and Southwest. Congress was advised to fund and hire new Indian agents in these new territories.[92] A report presented to Congress in 1850 by William Carey Jones surmised information he gathered on land title in California. Jones concluded that Spanish and Mexican law didn't recognize the right of natives to owning their homelands.[92] After the admission of California as an American state the topic of relations with its indigenous peoples was raised in the Senate once more. Charles Fremont presented legislation that promoted the forced seizure of their lands for resale to American colonists. He however felt that the natives had legal right to their own territories and had to be compensated for their territorial losses. This was far from a universal opinion in the Senate as some legislators felt California Indigenous had no legal right to their own homelands.

In September the Senate passed two bills that formulated Federal policy with Californian Natives. Three commissioners were authorized to draft treaties with California Natives.[93] Redick McKee, O. M. Wozencraft, and George W. Barbour were appointed and began negotiations in 1851. However they collectively lacked expertise and familiarity with either California natives or how their societies utilized their territories.[94] The Commissioners eventually divided California into three areas to cover the large amount of travelling necessary to create treaties with every native group. This meant they were operating independent of each other. McKee was assigned the task of creating treaties with natives of Northern California. He and his entourage created agreements with natives in Humboldt Bay and the lower Klamath River. Later in September 1851 he arrived in Shasta territory.

Local conditions

McKee toured the Shasta territories; inspecting the Shasta and Scott vallies in particular. It was concluded that only the Scott could support a reservation and the agricultural work necessary to feed the Shasta.[95] This assessment was due to the scarcity of agriculturally viable land in the Klamath Mountains. More promising areas did exist nearby but they were in Oregon.[96] The Shasta wanted to retain the entirety of Scott Valley for their designated reservation. American colonists from Scott Bar and Shasta Butte City contended for possession of the valley as well. Federal officials consulted with them for what they desired in a treaty with the Shasta.[97] They called for the removal of all Shasta to a reservation placed on the headwaters of the Shasta River.[96]

Gibbs proposal

George Gibbs was a member of McKee's delegation and left a record of its activities. There was a repeating cycle of violence and reprisals then ongoing in northern California. Local American militias were reported to be excessively violent in "revenging outrages" supposedly committed by natives.[98] Gibbs argued for the establishment of US Army post at or near the confluence of the Trinity and Klamath Rivers. He felt it was necessary to maintain peaceable relations between the colonists and various natives peoples in the Klamath Basin. The government was suggested to model its native policies in Northern California after those of employed by the Hudson's Bay Company in the Columbia Department. Select individuals would be given material patronage which would assist them in gaining prominence among their local settlements. This in turn would simplify interactions with various native cultures as power gradually centralized under amendable leadership.[98] There wasn't a fort located in this vicinity until 1858, when Fort Gaston was established in modern Hoopa.

Treaty

The terms drafted by McKee for an agreement were not particularly favored by the Shasta or American settlers. The reservation was placed in Scott Valley although the majority of the valley was to remain in colonist possession. The location of the Shasta reservation was apparently accepted, albeit grudgingly, by most American colonists of the area. Some had purchased expensive land grants from other Americans. A variation of the Donation Land Claim Act was expected to soon be enacted in California.[99] Financial compensation from Congress or the Indian Department was expected by Americans with properties within the reservation boundaries.[99]

The area specified in the treaty for the reservation was estimated by McKee to contain four or five square miles of arable land.[100] The Shasta were promised to receive "free of charge" 20,000 pounds of flour, 200 cattle, a large inventory of garments, and a multitude of household goods from the Federal government throughout 1852 and 1853.[100] Funding was to be appropriated in Congress for employing a carpenter, a group of farmers and several teachers on the reservation. Prospecting along the Scott river was to be allowed for two additional years. Any additional mining operations within the reservation had a single year to continue.[100]

At the end of the discussions a bull was presented to the Shasta. A celebration was held which lasted late into the evening.[101] Gibbs recorded the day assigned for the formal signing of the treaty:

"In the morning, November 4th, the treaty was explained carefully as drawn up and the bounds of the reservation pointed out on a plat. In the afternoon it was signed in the presence of a large concourse of whites and Indians, with great formality."[102]

Alleged poisoning

Some ethnographic informants gave accounts of three thousand Shasta being present at the ceremony. They were reportedly served beef poisoned with strychnine by American officials.[103] Survivors told of spending weeks locating the deceased. Only around 150 Shasta were said to have survived.[103]

Failure

The treaties negotiated by McKee, Barbour, and Wozencraft amounted to 18. McKee pressed for the California legislature to accept the treaties. He argued the reservations were designed to allocate natives to keep portions of their traditional lands while keeping open the many areas bearing gold. The commissioners were stated to have always consulted with local American colonists and miners in establishing the borders of each reservation. Pointedly he went on to argue that unless if someone were to "propose a more humane and available system" the reservations had to be acknowledged by the California Government.[104] The state rejected all treaties and instructed its representatives in Washington, D.C. to lobby against them as well.

The treaties were endorsed by President Millard Fillmore, commissioner of Indian affairs Luke Lea and the recently appointed superintendent of Indian affairs for California Edward Fitzgerald Beale.[105] The treaties were sent the Committee on Indian Affairs in June 1852. After a closed session the treaties were rejected. Ellison suggested that the vast amount of land set aside by the treaties and the expenditures allocated by the commissioners made the agreements unpopular in Congress.[105] In total about 11,700 square miles (30,000 km2) or about 7% of the total land area of California was to contain the 18 reservations.[105] Heizer concluded that the process of drafting treaties made by the Commissioners and their eventual rejection in the U.S. Congress "was a farce from beginning to end..."[94]

Continued conflicts

Violence against the Shasta continued after the agreement with McKee. On 18 January 1852 three American men attacked and killed a Shasta individual without provocation on Humbug Creek.[106] A panic arose among the local Shasta who fled into the nearby mountains. This senseless killing caused a panic among the miners. They feared that this breach of the new treaty would provoke conflict with the Shasta. McKee was requested to return to the area and mediate a solution. Although one of the murderers escaped two of the men were captured by the miners. The slain man's familial relations were given six blankets as compensation pending a ruling of the three murderers.[106]

In July 1852 a party of miners found and killed fourteen Shasta people in Shasta Valley in revenge for the murder of a white man.[107] This escalation of violence continued to deplete the number of Shasta. Their reprisals against white violence were to protect "their communities from assault, abduction, unfree labor, rape, murder, massacre, and, ultimately, obliteration."[108]

Americans in Cottonwood organized the "Squaw Hunters" in January 1854. It was an armed group made to "get squaws, by force, if necessary…"[109] That month they went to a nearby cave where over 50 Shasta were residing. The Squaw Hunters attacked the Shasta there and killed 3 children, 2 women and 3 men.[109] Afterwards they claimed the Shasta were preparing for an attack on Americans. This false rumor created a panic among settlers. 28 men gathered to attack the cave. In the skirmish four Americans and one Shasta died.[109] Federal troops from Fort Jones and local volunteers assembled on the Klamath River five miles away from the cave. In total about fifty armed Americans were present. Additional forces from Fort Lane arrived with a howitzer. It was fired at the cave multiple times. Representatives of the headman known to settlers as "Bill" pressed for peace and of their innocence.[109] Military officials concluded that this was the case. American colonists were held accountable for the outbreak of violence.[109] Smith's decision to cease hostilities with Bill's people was unpopular with local American settlers. He was claimed to have left Americans "wholly unprotected from the ruthless and murderous incursions of these savages..."[110]

In late April 1854 a group of miners found and killed 15 Shasta. These murders were committed in retaliation for some cattle having been stolen.[111]

In May 1854 a Shasta man was accused of attempting to rape an American woman.[112] A directive issued from Fort Jones called for the man to be captured and eventually presented to civil authorities in Yreka. Indian agent Rosborough informed representatives of Bill of the military order. The man accused of the rape attempt wasn't from Bill's band.[113] Despite this Bill pushed for a guarantee that the man wouldn't be hanged. Fort Jones command insisted this wasn't possible. The commanding officer declared that if the man wasn't delivered soon all Shasta would be held responsible for his actions. A large party of "De Chute" natives (likely the Tenino)[114] visiting the area were threatened to be employed in military reprisals against the Shasta.[112] Dignitaries from the Irauitsu expressed support in capturing the man though they also didn't want him to be hung.

The accused Shasta was eventually presented to authorities in Yreka. As Fort Jones' commanding officer was absent from the area he was allowed to temporarily depart the town on the condition he remain in the area.[115] A captain was eventually ordered to visit the nearby Shasta settlement where the man was then residing. Headman Bill and several Shasta accompanied the American officer. Upon reaching the village the man was collected. On 24 May while returning to Yreka the Shasta group was attacked on the Klamath River by a group of American settlers and "De Chutes".[115] The American officer told the Shasta to flee while he attempted to talk the party down. The armed men refused to allow the Shasta to leave peaceably and shot at them. Two Shasta were killed instantly and three seriously injured. Headman Bill was among those wounded and struggled against being scalped by Americans. Eventually they succeeded in removing his scalp and threw him into the Klamath River while he remained alive. Lt. Bonnycastle decried the "cowardly and brutal murder" committed by the American settlers who apparently escaped unpunished for their actions.[115]

On 17 May 1854 some Shasta warriors attacked a mule train in the Siskiyou Mountains. Two Americans were leading the mules. One was killed in the skirmish while the other man escaped to Cottonwood. Five horses and a mule taken by the Shasta.[116]

Rogue River Wars

The Irkirukatsu Shasta joined their Takelma neighbors in militarily resisting American territorial encroachment during the Rogue River Wars. Incoming colonists implemented agricultural operations across the Rogue Valley in 1852 and 1853.[117] Open meadows became plowed and fenced into private farms. Oak forests were timbered for building supplies and additional agricultural land. Livestock such as pigs dug and ate the bulbs and roots to important flowering species.These practices quickly ruined many food sources for the indigenous of the region, including camas, acorns and seeds from a variety of grass species.[117]

A group of 150 to 300 Shasta gathered in the upper Rogue River basin in the winter of 1851 to 1852.[118] Reportedly they had congregated to settle a dispute over a woman and were close to finishing negotiations. The American witness to the proceedings considered it largely a "war expedition".[118] However the peaceable conclusion to the matter through material compensation followed traditional Shasta means of dispute resolution.[16]

In early August 1853 a settler named Edwards residing near modern-day Phoenix was found slain in his cabin.[119] Edwards' death incited a harsh response from American settlers. Militias were organized to begin indiscriminately attacking any natives in the Rogue River basin.[120] About a month prior he had visited an Dakubetede settlement in the Applegate Valley and stole a Shasta slave. The abduction was tolerated by Americans and claims for compensation from the former slave owner were ignored. Contemporaries in Jacksonville considered this dispute to the cause of the murder.[120] The Irkirukatsu Shasta were targeted in particular as they were considered particularly unwelcoming and aggressive against American colonists. They received help from some Klamath River Shasta who were expelled from their home territories by miners.[120]

Eventually the Shasta and Takelma were pressed into accepting deportation from the Rogue Valley. American officials under Joel Palmer met with the leadership of the Irkirukatsu Shasta, "Grave Creek Umpqua" and the unrelated Shasta Costa on 18 November 1854.[121] The "Chasta Treaty" was signed between the groups, although its terms were far from clear to the indigenous leaders.[122] The fifth article stipulated that the Federal government was to fund and staff several facilities on the eventual reservation the Oregon Shasta and their neighbors were to be relocated to. This included a hospital, a schoolhouse, and two blacksmith shops.[121]

Reservation life

Life on the reservations was a challenging adjustment for the Shasta. The Grand Ronde in November 1856 had an estimated population of 1,025 natives, with 909 either Takelma or Shasta although this perhaps including some Shasta Costa or other natives of Southern Oregon.[122] On 21 September 1857 a federal government official visited the Siletz Reservation. He estimated the Shasta and Takelma to number 544 there.[123] The Superintendent Newsmith reported that some of the terms of the 1854 "Chasta Treaty" had yet to be implemented by 1858. Once relocated to the Siletz Reservation the promised blacksmiths, "school teachers and medical officials had to be shared among all natives residing there, rather than just the signatories of the "Chasta Treaty".

See also

Notes

- U.S. Census 2010, p. 10.

- Dixon 1907, p. 387-390.

- Kroeber 1925, pp. 285-291.

- Holt 1946, pp. 301-302.

- Clark 2009, pp. 48, 218, 224.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 384-385.

- Merriam 1926, p. 525.

- Renfro 1992, pp. 8, 15.

- Maloney 1945, p. 232.

- Garth 1964, p. 48.

- Hodge 1905, p. 520.

- Stern 1900, p. 218 cit. 33.

- Clark 2009, p. 224.

- Silver 1978, pp. 211-214.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 251-252.

- Holt 1946, p. 316.

- Merriam 1967, pp. 233-235.

- Silver 1978, pp. 221-223.

- Dixon 1907, p. 496.

- Merriam 1930, pp. 288-289.

- Dixon 1931, p. 264.

- Voegelin 1942, p. 209.

- Kroeber 1925, pp. 883-884.

- Renfro 1992, p. 9.

- Cook 1976a, p. 177.

- Cook 1976b, p. 6.

- Kroeber 1925, pp. 293-294.

- Renfro 1992, p. 34.

- Voegelin 1942, pp. 174-175.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 431-432.

- Voegelin 1942, p. 170.

- Holt 1946, pp. 308-309.

- Voegelin 1942, pp. 177-181.

- Voegelin 1942, p. 179.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 423-424.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 416-422.

- Holt 1946, pp. 305-308.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 447-449.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 396-399.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 412-413.

- Voegelin 1942, p. 202.

- Renfro 1992, pp. 44-45.

- Wilkes 1845, pp. 239-240.

- Renfro 1992, p. 46.

- Silver 1978, p. 218.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 439-441.

- Dixon 1907, p. 452.

- Holt 1946, p. 313.

- Kroeber 1925, pp. 899-904.

- Kroeber 1936, p. 102.

- Dixon 1907, p. 436.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 1.

- Sample 1950, pp. 8-9.

- Dixon 1907, pp. 398-399.

- Sapir 1907, p. 253 cit. 3.

- Gray 1987, p. 18.

- Spier 1930, p. 41.

- Sample 1950, p. 3.

- Spier 1930, p. 31.

- Sample 1950, p. 8.

- Garth 1953, p. 131.

- Garth 1953, p. 198.

- Kniffen 1928, p. 314.

- Du Bois 1935, p. 37.

- Du Bois 1935, p. 25.

- Du Bois 1935, pp. 131-132.

- Silver 1978, p. 212.

- Edwards 1890, p. 29.

- Edwards 1890, pp. 40-41.

- Edwards 1890, pp. 42-43.

- Wilkes 1845, p. 518.

- Wilkes 1845, pp. 237-239.

- Colvocoresses 1852, pp. 292-293.

- Wilkes 1845, p. 240.

- Gudde 2010, p. 325.

- Morse 1851b, p. 2.

- Renfro 1992, p. 91.

- Morse 1851a, p. 2.

- Morse 1852a, p. 2.

- Kemble & Durivage 1850a, p. 2.

- Kemble & Durivage 1850c, p. 3.

- Morse 1852d, p. 2.

- Ewer & Fitch 1851c, p. 2.

- Ewer & Fitch 1851b, p. 2.

- Taylor & Massett 1851a, p. 2.

- U.S. Congress 1853, p. 212.

- Morse 1851c, p. 2.

- Ewer & Fitch 1850b, p. 2.

- Morse 1852c, p. 2.

- Kemble & Durivage 1850b, p. 3.

- Ewer & Fitch 1850a, p. 2.

- Ellison 1922, pp. 44-46.

- Madley 2017, pp. 163-164.

- Heizer 1972, pp. 4-5.

- U.S. Congress 1853, p. 226.

- U.S. Congress 1853, p. 224.

- U.S. Congress 1853, pp. 219-220.

- Gibbs 1853, p. 144.

- Gibbs 1853, pp. 171-172.

- U.S. Congress 1920, p. 50.

- U.S. Congress 1853, p. 211.

- Gibbs 1853, p. 173.

- Renfro 1992, p. 92.

- Morse 1852b, p. 4.

- Ellison 1922, pp. 57-58.

- Schnebly 1852a, p. 2.

- Morse 1852e, p. 2.

- Madley 2017, pp. 198-199.

- U.S. Congress 1855, pp. 18-19.

- Anthony 1854a, p. 2.

- Anthony 1854b, p. 2.

- U.S. Congress 1855, pp. 77-78.

- Whaley 2010, p. 202-203.

- Clark 2009, p. 283.

- U.S. Congress 1855, pp. 80-83.

- Anthony 1854, p. 2.

- Beckham 1996, pp. 81-82, 129.

- Schnebly 1852b, p. 2.

- Beckham 1996, p. 115.

- Beckham 1996, p. 125.

- Kappler 1904, pp. 655-656.

- Browne 1858, p. 22.

- Browne 1858, pp. 37-38.

References

- Anthony, James (14 February 1854a). "Indian Difficulties in the North". 6 (904). Retrieved 5 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anthony, James (24 April 1854b). "From Yreka–Indians". 7 (967). Retrieved 5 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckham, Stephen Dow (1996). Requiem for a people: The Rogue Indians and Frontiersmen. Northwest reprints. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 9780870715211.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Browne, J. Ross (1858), "Report on the condition of the Indian reservations in the Territories of Oregon and Washington", Executive Documents printed by order of the House of Representatives during the first session of the Thirty-Fifth Congress, 1857-1858., Washington, D.C.: James B. Steedman, pp. 2–44, retrieved 18 February 2018

- Clark, Patricia Roberts (2009). Tribal Names of the Americas. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-3833-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Colvocoresses, George M. (1852). Four Years in a Government Exploring Expedition. New York: Cornish, Lamport & Co. Retrieved 5 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cook, Sherburne F. (1976). The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization. Berkeley: University of California press. ISBN 9780520031425. Retrieved 28 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cook, Sherburne F. (1976b). The Population of the California Indians, 1769-1970. Berkeley: University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Roland B. (1907). "The Shasta". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. The Huntington California Expedition. 17 (5): 381–498. Retrieved 28 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Roland B. (1931). "Dr. Merriam's "Tló-hom-tah'-hoi"". American Anthropologist. 33 (2): 264–267. doi:10.1525/aa.1931.33.2.02a00250.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Du Bois, Cora (1935). Wintu Ethnography. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 36. University of California Press. pp. 1–147. Retrieved 2 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edwards, Philip Leget (1890). California in 1837. Diary of Col. Philip L. Edwards Containing An Account of a Trip to the Pacific Coast. A. J. Johnston & Co. Retrieved 16 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ellison, William H. (1922). "The Federal Indian Policy in California, 1846-1860". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 9 (1): 37–67. doi:10.2307/1886099.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ewer, F. C.; Fitch, G. Kenyon, eds. (14 October 1850). "The North-Western Indians". Sacramento Transcript. 1 (141). Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Ewer, F. C.; Fitch, G. Kenyon, eds. (12 December 1850a). "Editors of the Transcript". Sacramento Transcript. 2 (42). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ewer, F. C.; Fitch, G. Kenyon, eds. (20 January 1851a). "Intelligence Respecting the Klamath and Scott's Rivers". Sacramento Transcript. 2 (73). Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Ewer, F. C.; Fitch, G. Kenyon, eds. (14 February 1851b). "Highly Important from Scott's River". Sacramento Transcript. 2 (95). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ewer, F. C.; Fitch, G. Kenyon, eds. (18 April 1851c). "The Discovery in Shasta Valley". Sacramento Transcript. 3 (17). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garth, Thomas R. (1964). "Early Nineteenth Century Tribal Relations in the Columbia Plateau". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 20 (1): 43–57. JSTOR 3629411.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garth, Thomas R. (1953). Atsugewi Ethnography. Anthropological Records. 14. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved 27 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibbs, George (1853). "Journal of the Expedition of Colonel Redick McKee, United States Indian Agent, through North-Western California. Performed in the Summer and Fall of 1851". In Schoolcraft, Henry R. (ed.). Information respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. pp. 99–177. Retrieved 2 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gray, Dennis J. (1987). The Takelmas and Their Athapascan Neighbors: A New Ethnographic Synthesis for the Upper Rogue River Area of Southwestern Oregon (PDF). University of Oregon Anthropological Papers. Eugene, Oregon: University of Oregon Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gudde, Erwin G. (2010). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names (4th ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26619-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heizer, Robert F. (1972). The Eighteen Unratified Treaties of 1851-1852 between the California Indians and the United States Government (PDF). Berkeley: University of California. Retrieved 27 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hodge, Frederick W. (1910). Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- Holt, Catherine (1946). Kroeber, Alfred (ed.). Shasta Ethnography. Anthropological Records. 3. University of California Press. pp. 1–338. Retrieved 28 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemble, Edward C.; Durivage, J. E., eds. (14 August 1850a). "Latest from Humboldt Bay". Daily Alta California. 1 (193). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemble, Edward C.; Durivage, J. E., eds. (20 August 1850b). "New Harbor Improvements". Daily Alta California. 1 (201). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemble, Edward C.; Durivage, J. E., eds. (8 November 1850c). "The town of Klamath". Daily Alta California. 1 (280). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kappler, Charles J., ed. (1904). Indian affairs. Laws and treaties. 2. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kent, Willam Eugene (2000), The Siletz Indian Reservation, 1855-1900 (M.S.), Dissertations and Theses, Portland, OR: Portland State University, doi:10.15760/etd.2114, retrieved 17 February 2018

- Kniffen, Fred B. (1928). Achomawi Geography. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 23. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. pp. 297–332. Retrieved 27 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1925). Handbook of the Indians of California. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Retrieved 28 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1936). "Culture element distributions: III, Area and climax". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 37 (4). University of California Press: 101–115. Retrieved 2 February 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Library, University of Oregon (12 May 1854), Lyons, D. J. (ed.), "Killing of Indians", Umpqua Weekly Gazette (1854/05/12), retrieved 26 February 2018

- Madley, Benjamin (2017). An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18136-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maloney, Alice Bay (1945). "Shasta Was Shatasla in 1814". California Historical Society Quarterly. 24 (3): 229–234. JSTOR 25155920.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merriam, C. Hart (1926). "Source of the name Shasta". Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 16 (19): 522–525. JSTOR 24522525.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merriam, C. Hart (1930). "THE NEW RIVER INDIANS TLÓ-HŌTM-TAH'-HOI". American Anthropologist. 32 (2): 280–293. doi:10.1525/aa.1930.32.2.02a00030.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merriam, C. Hart (1967). "Ethnographic Notes on California Indian Tribes. Part II". University of California Archaeological Survey. 68 (2). University of California Press: 167–256. Retrieved 3 February 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Morse, John F., ed. (24 July 1851a). "The Northern Indians". Sacramento Daily Union. 1 (109). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morse, John F., ed. (29 August 1851c). "Shasta County". Sacramento Daily Union. 1 (139). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morse, John F., ed. (8 November 1851d). "From Scott's River–The Indians". Sacramento Daily Union. 2 (200). Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Morse, John F., ed. (9 February 1852a). "Late from Shasta Plains–Indian Troubles". Sacramento Daily Union. 2 (279). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morse, John F., ed. (25 March 1852b). "The Address of Col. Redick McKee". Sacramento Daily Union. 3 (315). p. 4. Retrieved 27 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morse, John F., ed. (1 April 1852c). "Letter from Shasta". Sacramento Daily Union. 3 (321). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morse, John F., ed. (16 June 1852d). "Novel Arrival". Sacramento Daily Union. 3 (386). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morse, John F., ed. (19 July 1852e). "From the Interior". Sacramento Daily Union. 3 (413). Retrieved 5 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, R. H.; Massett, Stephen, eds. (25 February 1851). "Sacramento City Correspondence". Marysville Daily Herald. 1 (59). Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Renfro, Elizabeth (1992). The Shasta Indians of California and their neighbors. Happy Camp, CA: Naturegraph Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-87961-221-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sample, Laetitia L. (1950). "Trade and Trails in Aboriginal California". Reports of the University of California Archaeological Survey (8). University of California: 1–30. Retrieved 28 January 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Sapir, Edward (1907). "Notes on the Takelma Indians of Southwestern Oregon". American Anthropologist. American Anthropologist New Series. 9 (2): 251–275. doi:10.1525/aa.1907.9.2.02a00010. JSTOR 659586.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silver, Shirley (1978). "Shastan Peoples". In Heizer, Robert F. (ed.). California. Handbook of North American Indian. 8. pp. 211–224.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Library, University of Oregon (24 February 1852a), Schnebly, D. J. (ed.), "Letter from the Mines.–Difficulty with the Indians", Oregon Spectator (1852/02/24), retrieved 26 February 2018

- Library, University of Oregon (2 March 1852b), Schnebly, D. J. (ed.), "From the Shasta mines", Oregon Spectator (1852/03/02), retrieved 26 February 2018

- Spier, Leslie (1930). Kroeber, Alfred L.; Lowie, Robert (eds.). Klamath Ethnography. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 30. University of California Press. Retrieved 28 January 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stern, Theodore (1993). Chiefs and Chief Traders, Indian Relations at Fort Nez Percés. 1. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87071-368-2. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- U.S. Census (2010), American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico (PDF), retrieved 27 February 2018

- U.S. Congress (1853). Documents of the Senate of the United States, printed by order of the Senate during the Special Session called March 4, 1853. United States Congressional serial set. Washington, D.C.: Robert Armstrong. Retrieved 22 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- U.S. Congress (1855). "President of the United States, communicating the instructions and correspondence between the government and Major General Wool, in regard to his operations on his operations on the coast of the Pacific...". Executive Documents printed by order of the Senate of the United States, Second Session, Thirty-Third Congress, 1854-'55. 6. Beverley Tucker. pp. 1–128. Retrieved 4 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- U.S. Congress (1920). Indian tribes of California: hearings before a subcommittee of the Committee on Indian Affairs, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, second session, March 23, 1920. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. Retrieved 18 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Voegelin, Erminie W. (1942). Culture Element Distributions: XX Northeast California. University of California Anthropological Records. 7. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 47–251. Retrieved 11 February 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whaley, Gray (2010), Oregon and the Collapse of Illahee U.S. Empire and the Transformation of an Indigenous World, 1792-1859, Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press

- Wilkes, Charles (1845). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition. During the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. 5. Philadelphia: C. Sherman.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)