Kumeyaay

The Kumeyaay, also known as Tipai-Ipai, are a tribe of Indigenous peoples of the Americas who live at the northern border of Baja California in Mexico and the southern border of California in the United States. Their Kumeyaay language belongs to the Yuman–Cochimí language family.

Anthony Pico, chairman of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| As of 1990, 1,200 on reservations; 2,000 off-reservation[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Ipai, Kumeyaay, Tipai, English, and Spanish | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Luiseño, Cocopa, Quechan, Paipai, and Kiliwa |

The Kumeyaay consist of two related groups, the Ipai and Tipai. The San Diego River loosely divided the two coastal groups' historical homelands. The Ipai lived to the north, from Escondido to Lake Henshaw, while the Tipai lived to the south, in lands including the Laguna Mountains, Ensenada, and Tecate.

Name

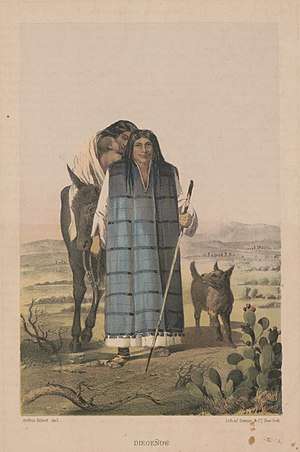

The Kumeyaay or Tipai-Ipai were formerly known as the Kamia or Diegueño. In Spanish, the name is commonly spelled Kumiai.

The term Kumeyaay translates "those who face the water from a cliff".[2] It may also come from the Kiliwa word kumeey meaning "man (human being)" or "people." Both Ipai/Iipay and Tipai mean "man (human being)" or "people."[3]

Language

Nomenclature and tribal distinctions are not widely agreed upon. The general scholarly consensus (e.g., Langdon 1990) recognizes three separate languages: Ipai (Iipay) (Northern Kumeyaay), Kumeyaay proper (including the Kamia/Kwaaymii), and Tipai (Southern Kumeyaay) in northern Baja California. Other authorities (e.g., Luomala 1978 and Pritzker 2000) see only two: Ipai and Tipai.

However, this notion is not supported by speakers of the language (actual Kumeyaay people) who contend that within their territory, all Kumeyaay (Ipai/Tipai) can understand and speak to each other, at least after a brief acclimatization period.[4] All three languages belong to the Delta–California branch of the Yuman language family, to which several other linguistically distinct but related groups also belong, including the Cocopa, Quechan, Paipai, and Kiliwa.

Linguist Margaret Langdon is credited with doing much of the early work on documenting the language.[5]

History

Evidence of settlement in what is today considered Kumeyaay territory may go back 12,000 years.[6] 7000 BCE marked the emergence of two cultural traditions: the California Coast and Valley tradition and the Desert tradition.[7] The Kumeyaay had land along the Pacific Ocean from present Oceanside, California in the north to south of Ensenada, Mexico and extending east to the Colorado River.[8] The Cuyamaca complex, a late Holocene complex in San Diego County is related to the Kumeyaay peoples.[9] The Kumeyaay tribe also used to inhabit what is now a popular state park, known as Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve.[10]

One view holds that historic Tipai-Ipai emerged around 1000 years ago, though a "proto-Tipai-Ipai culture" had been established by about 5000 BCE.[1] Katherine Luomola suggests that the "nucleus of later Tipai-Ipai groups" came together around AD 1000.[7] The Kumeyaay themselves believe that they have lived in San Diego for 12,000 years.[11] At the time of European contact, Kumeyaay comprised several autonomous bands with 30 patrilineal clans.[3]

Spaniards entered Tipai-Ipai territory in the late 18th century, bringing with them non-native, invasive flora, and domestic animals, which brought about degradation to local ecology. Under the Spanish Mission system, bands living near Mission San Diego de Alcalá, established in 1769, were called Diegueños.[3] After Mexico took over the lands from Spain, they secularized the missions in 1834, and Ipai and Tipais lost their lands; band members had to choose between becoming serfs, trespassers, rebels, or fugitives.[12]

From 1870 to 1910, American settlers seized lands, including arable and native gathering lands. In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant created reservations in the area, and additional lands were placed under trust patent status after the passage of the 1891 Act for the Relief of Mission Indians. The reservations tended to be small and lacked adequate water supplies.[13]

Kumeyaay people supported themselves by farming and agricultural wage labor; however, a 20-year drought in the mid-20th century crippled the region's dry farming economy.[14] For their common welfare, several reservations formed the non-profit Kumeyaay, Inc.[15]

Education

The Kumeyaay Community College was created by the Sycuan Band to serve the Kumeyaay-Diegueño Nation, and describes its mission as "to support cultural identity, sovereignty, and self-determination while meeting the needs of native and non-Native students." The college's focus is on "Kumeyaay History, Kumeyaay Ethnobotany and traditional Indigenous arts." It "serves and relies on resources from the thirteen reservations of the Kumeyaay Nation situated in San Diego county."[16] In the fall of 2016, Cuyamaca College began offering an associate degree in Kumeyaay Studies with courses at its Rancho San Diego campus, as well as at Kumeyaay Community College on the Sycuan reservation.[17]

Population

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. In 1925, Alfred L. Kroeber proposed that the population of the Kumeyaay in the San Diego region in 1770 had been about 3,000.[18] More recently, Katharine Luomala points out that this estimate depended on calculations of rates of baptisms at the Mission, and as such "ignores the unbaptized." She suggests that the region could have supported 6,000-9,000 people.[19] Florence C. Shipek goes further, estimating 16,000-19,000 inhabitants.[20]

In the late eighteenth century, it is estimated that the Kumeyaay population was between 3,000 and 9,000.[1] In 1828, 1,711 Kumeyaay were recorded by the missions. The 1860 federal census recorded 1,571 Kumeyaay living in 24 villages.[19] The Bureau of Indian Affairs recorded 1,322 Kumeyaay in 1968, with 435 living on reservations.[19] By 1990, an estimated 1,200 lived on reservation lands, while 2,000 lived elsewhere.[1]

Tribes and reservations

The Kumeyaay live on 13 reservations in San Diego County, California in the United States and are enrolled in the following federally recognized tribes:[21]

- Campo Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Campo Indian Reservation

- Capitan Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of California:

- Barona Group of Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of the Barona Reservation

- Viejas (Baron Long) Group of Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians of the Viejas Reservation

- Ewiiaapaayp Band of Kumeyaay Indians

- (formerly the Cuyapaipe Community of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Cuyapaipe Reservation)

- Inaja Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Inaja and Cosmit Reservation

- Jamul Indian Village of California

- La Posta Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the La Posta Indian Reservation

- Manzanita Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Manzanita Reservation

- Mesa Grande Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Mesa Grande Reservation

- San Pasqual Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of California

- Iipay Nation of Santa Ysabel (formerly Santa Ysabel Band of Diegueno Mission Indians of the Santa Ysabel Reservation)

- Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation

They live on five communities in Baja California, including:

- Juntas de Neji

- La Huerta

- San Antonio Necua

- Santa Catarina

- San José de la Zorra[11]

See also

- Kumeyaay traditional narratives

- Kumeyaay astronomy

- O. M. Wozencraft negotiated the Treaty of Santa Ysabel on January 7, 1852.[22]

- Sycuan Institute on Tribal Gaming at San Diego State University

- Viejas Arena at San Diego State University

- Viejas casino

Notes

- Pritzker 2000, p. 145

- Hoffman & Gamble 2006, p. 71

- Luomala 1978, p. 592

- Smith 2005

- "Margaret Langdon; linguist helped write first local Indian dictionary | The San Diego Union-Tribune". legacy.sandiegouniontribune.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- Erlandson et al. 2010, p. 62

- Luomala 1978, p. 594

- Kumeyaay.info: Kumeyaay Lands 1769-2000

- "A Glossary of Proper Names in California Prehistory." Society for California Archaeology. (retrieved 12 Aug 2011)

- "Native Americans", Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve, retrieved 10 October 2016

- "The Kumeyaay of Southern California", The Kumeyaay Information Village, retrieved 10 October 2016

- Luomala 1978, p. 595

- Shipek 1978, p. 610

- Shipek 1978, p. 611

- Shipek 1978, p. 616

- "Kumeyaay Community College", Kumeyaay Community College, retrieved October 10, 2016

- Huard, Christine (15 August 2016). "College expands Kumeyaay studies program". The San Diego-Union Tribune. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 88

- Luomala 1978, p. 596

- Shipek 1986, p. 19

- "Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs Notice 145A2100DD/A0T500000.000000/AAK3000000: Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible to Receive Services from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register, January 2015 (PDF). Federal Register. 80. Government Publishing Office. January 14, 2015. pp. 1942–1948. OCLC 1768512. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- Carrico, Richard L. (Summer 1980). "San Diego Indians and the Federal Government Years of Neglect, 1850-1865". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego Historical Society. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

Bibliography

- Erlandson, Jon M.; Rick, Torben C.; Jones, Terry L.; Porcasi, Judith F. (2010), "One If by Land, Two If by Sea: Who Were the First Californians?", in Jones, Terry L.; Klar, Kathryn A. (eds.), California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity, Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, pp. 53–62, ISBN 978-0-7591-1960-4.

- Hoffman, Geralyn Marie; Gamble, Lynn H. (2006), A Teacher’s Guide to Historical and Contemporary Kumeyaay Culture, Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias, San Diego State University.

- Kroeber, A. L. (1925), "Handbook of the Indians of California", Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, Washington, DC (78).

- Langdon, Margaret (1990), Redden, James E. (ed.), "Diegueño: how many languages?", Proceedings of the 1990 Hokan-Penutian Languages Workshop, University of Southern Illinois, Carbondale: 184–190.

- Luomala, Katharine (1978), "Tipai-Ipai", in Heizer, Robert F. (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, 8 (California), Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 592–609, ISBN 0-16004-574-6.

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2000), "Tipai-Ipai", A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 145–147, ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Shipek, Florence C. (1978), "History of Southern California Mission Indians", in Heizer, Robert F. (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 610–618, ISBN 0-87474-187-4.

- Shipek, Florence C. (1986), "The Impact of Europeans upon Kumeyaay Culture", in Starr, Raymond (ed.), The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Local Native Americans, San Diego: Cabrillo Historical Association, pp. 13–25, OCLC 17346424.

- Smith, Kalim H (2005), Language Ideology and Hegemony in the Kumeyaay Nation: Returning the Linguistic Gaze, University of California, San Diego. Master's Thesis.

Further reading

- Du Bois, Constance Goddard. 1904-1906. "Mythology of the Mission Indians: The Mythology of the Luiseño and Diegueño Indians of Southern California." The Journal of the American Folk-Lore Society, Vol. XVII, No. LXVI. p. 185-8 [1904]; Vol. XIX. No. LXXII pp. 52–60 and LXXIII. pp. 145–64. [1906].

- Miskwish, Michael C. Kumeyaay: A History Book. El Cajon, CA: Sycuan Press, 2007.

- Miskwish, Michael C, and Joel Zwink. Sycuan: Our People, Our Culture, Our History: Honoring the Past, Building the Future. El Cajon, Calif.: Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kumeyaay people. |

- Kumeyaay.info: The Kumeyaay Tribes Guide — Tribal Bands of the Kumeyaay Nation (Diegueño) — in San Diego County, California + Baja California state, México

- Kumeyaay Information Village, with educational materials for teachers

- Kumeyaay.com, information website of Larry Banegas, Barona Reservation

- Kumeyaay Indian Language

- Kumeyaay Community College and its *Kumeyaay Studies Program in conjunction with Cuyamaca College

- Kumeyaay Department at Cuyamaca College

- Mythology of the Mission Indians, by Du Bois, 1904-1906.

- Religious Practices of the Diegueño Indians, by T.T. Waterman, 1910.

- Kumeyaay (Diegueño) language overview at the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages

- A.R. Royo, "The Kumeyaay: San Diego County and Baja

- Corpus of Kumiai and Ko’alh spoken in Baja California, Mexico by Margaret Field from the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America, containing digital audio and hi-definition video from four Baja Kumiai communities: San Jose de la Zorra, La Huerta, Alamo-Neji, Necua and San Jose Tecate

- Kumeyaay Indians of Baja California on YouTube

- Samuel Brown recounts Viejas Reservation - Lesson 1 How to say Kumeyaay on YouTube (2010)