Maidu

The Maidu are an American Indian people of northern California. They reside in the central Sierra Nevada, in the watershed area of the Feather and American rivers. They also reside in Humbug Valley. In Maiduan languages, Maidu means "man."

Maidu coiled basket by Mary Kea'a'ala Azbill, circa 1900 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,500[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States of America ( | |

| Languages | |

| English, Maidu | |

| Religion | |

| Animistic (incl. syncretistic forms), other |

Local division

The Maidu people are geographically dispersed into many subgroups or bands who live and identify with separate valleys, foothills, and mountains in Northeastern Central California.[2] There are three subcategories of Maidu:

- The Nisenan or Southern Maidu occupied the whole of the American, Bear, and Yuba River drainages. They live in lands that were previously home to the Martis.[3]

- The Northeastern or Mountain Maidu, also known as Yamani Maidu, lived on the upper North and Middle forks of the Feather River.

- The Konkow (Koyom'kawi/Concow) came out of a valley between Cherokee, and Pulga, along the north fork of the Feather River and its tributaries. The Mechupda live in the area of Chico, California.

Population

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber estimated the 1770 population of the Maidu (including the Konkow and Nisenan) as 9,000.[4] Sherburne F. Cook raised this figure slightly, to 9,500.[5]

Kroeber reported the population of the Maidu in 1910 as 1,100. The 1930 census counted 93, following decimation by infectious diseases and social disruption. As of 1995, the Maidu population had recovered to an estimated 3,500.

Culture

The Maidu were hunters and gatherers.

Baskets and basket making

The Maidu women were exemplary basket weavers, weaving highly detailed and useful baskets in sizes ranging from thimble-sized to huge ones ten or more feet in diameter. The weaving on some of these baskets is so fine that a magnifying glass is needed to see the strands. In addition to making closely woven, watertight baskets for cooking, they made large storage baskets, bowls, shallow trays, traps, cradles, hats, and seed beaters. To make these baskets, they used dozens of different kinds of wild plant stems, barks, roots and leaves. Some of the more common were fern roots, red bark of the redbud, white willow twigs and tule roots, hazel twigs, yucca leaves, brown marsh grassroots, and sedge roots. By combining these different kinds of plants, the women made geometric designs on their baskets in red, black, white, brown or tan.[6]

Maidu elder Marie Potts explains, "The coiled and twining systems were both used, and the products were sometimes handsomely decorated according to the inventiveness and skill of the weaver and the materials available, such as feathers of brightly plumaged birds, shells, quills, seeds or beads- almost anything that could be attached."[6]

Subsistence

Like many other California tribes, the Maidu were primarily hunters and gatherers and did not farm. They practiced grooming of their gathering grounds, with fire as a primary tool for this purpose. They tended local groves of oak trees to maximize production of acorns, which were their principal dietary staple after being processed and prepared.

According to Maidu elder Marie Potts:

Preparing acorns as the food was a long and tedious process that was undertaken by the women and children. The acorns had to be shelled, cleaned and then ground into meal. This was done by pounding them with a pestle on a hard surface, generally a hollowed-out stone. The tannic acid in the acorns was leached out by spreading the meal smoothly on a bed of pine needles laid over-sand. Cedar or fir boughs were placed across the meal and warm water was poured all over, a process which took several hours, with the boughs distributing the water evenly and flavoring the meal.[6]

The Maidu used the abundance of acorns to store large quantities for harder times. Above-ground acorn granaries were created by the weavers.

Besides acorns, which provided dietary starch and fat, the Maidu supplemented their acorn diet with edible roots or tubers (for which they were nicknamed "Digger Indians" by European immigrants), and other plants and tubers. The women and children also collected seeds from the many flowering plants, and corms from wildflowers also were gathered and processed as part of their diet. The men hunted deer, elk, antelope, and smaller game, within a spiritual system that respected the animals. The men captured fish from the many streams and rivers, as they were a prime source of protein. Salmon were collected when they came upstream to spawn; other fish were available year-round.

Housing

Especially higher in the hills and the mountains, the Maidu built their dwellings semi-underground, to gain protection from the cold. These houses were sizable, circular structures twelve to 18 feet in diameter, with floors, dug as much as three feet below ground level. Once the floor of the house was dug, a pole framework was built. It was covered by pine bark slabs. A sturdy layer of earth was placed along the base of the structure. A central fire was prepared in the house at ground level. It had a stone-lined pit and bedrock mortar to hold heat for food preparation.

For summer dwelling, a different structure was built from cut branches tied together and fastened to sapling posts, then covered with brush and dirt. The summer shelters were built with the principal opening facing east to catch the rising sun, and to avoid the heat of afternoon sun.

Social organization

Maidu lived in small villages or bands with no centralized political organization. Leaders were typically selected from the pool of men who headed the local Kuksu cult. They did not exercise day-to-day authority but were primarily responsible for settling internal disputes and negotiating over matters arising between villages.

Religion

The primary religious tradition was known as the Kuksu cult. This central California religious system was based on a male secret society. It was characterized by the Kuksu or "big head" dances. Maidu elder Marie Potts says that the Maidu are traditionally a monotheistic people: "they greeted the sunrise with a prayer of thankfulness; at noon they stopped for meditation, and at sunset, they communed with Kadyapam and gave thanks for blessings throughout the day."[6] A traditional spring celebration for the Maidu was the Bear Dance when the Maidu honored the bear coming out of hibernation. The bear's hibernation and survival through the winter symbolized perseverance to the Maidu, who identified with the animal spiritually.[6]

The Kuksu cult system was also followed by the Pomo and the Patwin among the Wintun. Missionaries later forced the peoples to adopt Christianity, but they often retained elements of their traditional practices.

Languages

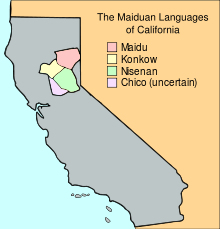

The Maidu spoke a language that some linguists believe was related to the Penutian family. While all Maidu spoke a form of this language, the grammar, syntax, and vocabulary differed sufficiently that Maidu separated by large distances or by geographic features that discouraged travel might speak dialects that were nearly mutually unintelligible.

There were four principal divisions of the language: Northeastern Maidu, Yamonee Maidu (known simply as Maidu); Southern Maidu or Nisenan; Northwestern Maidu or Konkow; and Valley Maidu or Chico.

Rock art

The Maidu inhabited areas in the northeastern Sierra Nevada. Many examples of indigenous rock art and petroglyphs have been found here. Scholars are uncertain about whether these date from previous indigenous populations of peoples or were created by the Maidu people. The Maidu incorporated these works into their cultural system, and believe that such artifacts are real, living energies that are an integral part of their world.

Tribes

Federally recognized

- Berry Creek Rancheria of Maidu Indians

- Enterprise Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Greenville Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Mechoopda Indian Tribe of Chico Rancheria

- Mooretown Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California

- Shingle Springs Band of Miwok Indians, Shingle Springs Rancheria (Verona Tract)

- Susanville Indian Rancheria

- United Auburn Indian Community of the Auburn Rancheria

Non-federally recognized

- Honey Lake Maidu Tribe

- KonKow Valley Band of Maidu Indians[7]

- Nisenan of Nevada City Rancheria

- Strawberry Valley Band of Pakan'yani Maidu (aka Strawberry Valley Rancheria)[8]

- Tsi Akim Maidu Tribe of Taylorsville Rancheria

- United Maidu Nation

- Colfax-Todds Valley Consolidated Tribe of the Colfax Rancheria[9]

Contemporary Maidu artists

- Dalbert Castro – Nisenan

- Wallace Clark – Koyom'kawi yepom (traditional arts)

- Frank Day – Konkow

- Harry Fonseca – Nisenan

- Janice Gould – Konkow Maidu

- Judith Lowry – Mountain Maidu

- Frank Tuttle[10] – KonKow Maidu

Nisenan Indian tribe

- Jacob A. Meders – Mechoopda-Konkow

Traditional narratives

Stories of K'odojapem/World-maker and Wepam/Trickster Coyote are particularly prominent in Maidu traditional narratives.[11][12]

Notes

- "California Indians and their Reservations." Archived 2015-09-25 at the Wayback Machine SDSU Library and Information Access.

- Johnson, Michael G. (2014). Encyclopedia of Native Tribes of North America. Buffalo, New York: Firefly Books. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-77085-461-1.

- Robbins, John (2000-12-14). "ACTION: Native American human remains and associated funerary objects:". thefederalregister.com. Archived from the original on 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2008-08-14.

- Kroeber (1925:883)

- Cook (1976:179)

- Potts, Marie (1977). The Northern Maidu. Happy Camp, California: Naturegraph Publishers Inc. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0879610719.

- Konkow Valley Band of Maidu Indians

- Strawberry Valley Rancheria

- ColfaxRancheria.com

- Frank Tuttle (Konkow Maidu, Yuki, Wailaki)

- "Maidu Indian Legends." Native Languages of the Americas. Retrieved 30 Dec 2011.

- Shipley, William. The Maidu Indian Myths and Stories of Hánc'ibyjim. 1991. (w/ forward by Gary Snyder)

References

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 78. Washington, D.C.

- Heizer, Robert F. 1966. Languages, Territories, and Names of California Indian Tribes. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Pritzker, Barry. 2000. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press, New York.

External links

- Maidu Headmen with Treaty Commissioners, July/August 1851

- Maidu Indians and Treaty Commissioners; Original Image at George Eastman House.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maidu. |