History of the Hungarian language

Hungarian is a Uralic language of the Ugric group. It has been spoken in the region of modern-day Hungary since the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in the late 9th century.

Hungarian's ancestral language probably separated from the Ob-Ugric languages during the Bronze Age. There is no attestation for a period of close to two millennia. Records in Old Hungarian begin fragmentarily in epigraphy in the Old Hungarian script beginning in the 10th century; isolated Hungarian words are attested in manuscript tradition from the turn of the 11th century. The oldest surviving coherent text in Old Hungarian is the Funeral Sermon and Prayer, dated to 1192.

The Old Hungarian period is by convention said to cover Medieval Hungary, from the initial invasion of Pannonia in AD 896, to the collapse of the Kingdom of Hungary following the Battle of Mohács of 1526. Printing begins during Middle Hungarian, from 1526 to 1772, i.e. from the first books printed in Hungarian to the Age of Enlightenment, which prompted language reforms that resulted in the modern literary Hungarian language.

The happenings of the 1530s and 1540s brought a new situation to the country: the time of Humanism – which only a few decades earlier, under Matthias Corvinus flourished – was over; the population, both in villages and towns, was terrorized by Ottoman raids; the majority of the country was lost; and the remainder began to feel the problems of the new Habsburg rule. This predicament caused backwardness in the cultural life as well.

However, Hungary, with the previously listed great territorial and human losses, soon entered into a new cultural era, the Reformation. This religious movement heartened many authors to find new ways. Cultural life was primarily based in Transylvania, but Royal Hungary also saw the rebirth of the Hungarian culture.

The first printed book written in Hungarian was printed in Kraków in the Kingdom of Poland in 1533. It is a partial Bible-translation, containing the Pauline epistles. The translation was done by Benedek Komjáti. The New Testament's first printed edition was published by János Sylvester (1541). He also composed the first scientific analysis of the Hungarian language, in 1539 – his work's title is "Grammatica Hungarolatina". Like Komjáti, Sylvester printed his works in Cracow.

The previous publications, however, were not Protestant in their sense; the first directly reformed Hungarian book was Imre Ozorai's Argument, published in Cracow first in 1535 and second in 1546.

Among other works, Aesop's Fables – a collection of moral short stories – were first translated into Hungarian by Gábor Pesti (1536). These are the first denoted Hungarian short stories. The first attempt to standardize Hungarian was done by Mátyás Bíró Dévai. He proposed a logical and feasible orthography to the language. His book, Orthographia, is known from its second edition, printed in 1549.

Prehistory

Separation from Common Uralic

The history of the Hungarian language begins with the Uralic era, in the Neolithic age, when the linguistic ancestors of all Uralic languages were living together, in the area of the Ural Mountains.[1]

| Category | Words in Hungarian | Reconstructed words in Proto-Uralic | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fishing, water | hal 'fish', tat '(a kind of) fish',[2] háló 'mesh', víz 'water', jó 'river',[3] ár 'flood', láp 'fen' | *kala, *totki 'tench', *kalaw, *weti, *juka, (Ugric) *sarV, *loppi | See note 2 & 3. |

| Hunting, animals | ideg 'nerve', ín 'fibre', íj 'bow', nyíl 'arrow', fogoly 'partridge', nyúl 'hare', holló 'raven' | *jänti 'string', *sëxni 'vein', *joŋsi, *ńëxli, *püŋi, *ńomala, *kulaka | |

| Daily life | fő(z) 'cook', fazék 'pan', mony 'bird egg',[4] fon 'spin', öv 'belt', vas 'iron' | *pexi(-ta), *pata, *muna, *puna 'braid', *wüŋä, *waśki | See note 4. |

| Family | apa 'father', fele(ség) 'wife', meny 'daughter-in-law', vő 'son-in-law', napa 'mother-in-law' | *ëppi 'father-in-law', *pälä 'half', *mińä, *wäŋiw, *ana-ëppi |

Many Hungarian words, particularly among the language's most basic vocabulary (cf. Swadesh list) are traced back to common Uralic origin: words of a corresponding shape occur in other Uralic languages as well and linguists have not been able to classify them as loanwords. Those that are not present in the Samoyedic languages are commonly also described as being of Finno-Ugric origin, but the existence of a definite distinction between "Uralic" and "Finno-Ugric" is disputed. (See Uralic languages#Family tree.)

As the Uralic unity disintegrated between the 4th and the 2nd millennium BC, the speakers of Samoyedic languages moved eastwards, while others, such as the Finnic and Hungarian speakers, moved westward. Hungarian and the Ob-Ugric languages show several similarities and are known as the Ugric group, which is commonly (but not universally) considered a proper sub-branch of Uralic: that is, the Hungarian and Ob-Ugric languages would descend from a common Proto-Ugric language. The speakers of Ugric languages were still living close together approximately until 1000 BC, when the ancestors of Hungarians separated for good from the Ob-Ugrians.

Proto-Hungarian

Around 1000 BC, the linguistic ancestors of the Hungarians had moved southwest from their previous territories, the region west of the Ural Mountains, the eastern frontier of Europe; hence the Hungarian language separated from its closest relatives, the Ob-Ugric languages, a small group divided further into the Mansi language and the Khanty language. (This split may have occurred only later, and their speakers were influenced by an Asian, possibly Western-Siberian tribe, as the Mansies and Khanties had moved northeast.) Proto-Hungarian likely had contacts with the Permic languages at this time, as indicated by a nontrivial number of shared vocabulary and sound developments (which are not found in the other Uralic languages).

The Hungarians gradually changed their way of living from settled hunters to nomadic cattle-raising. Their most important animals included sheep and cattle. There are no written resources on the era, thus only a little is known about it.

After a long journey, the Hungarians had settled the coastal region of the northeastern Black Sea, where they were significantly influenced by Turkic peoples. With the fall of Attila's empire, the Huns had receded to this area, and established their new state, which also ruled over the Hungarians. A possible memoir of this is a Hungarian myth: the saga of Hunor and Magor, who are said to be the common ancestors of the Huns and the Hungarians.

However, the Hunnish rule had not lasted long, as the Hungarians soon fell under Göktürk rule. The Göktürk Turk Empire flourished from the 6th century to the 8th century. This is very probably the time when the Hungarians were first exposed to the concept of writing, through the Göktürks' mediation. The latter used the Orkhon script or Turkic runic script, and reputedly the Old Hungarian script (rovásírás) descends from it.

The Hungarians call themselves Magyars (pronounced like madyar). The name Magyar once was the name of a Hungarian tribe, Megyer(i). It likely means "talking man". The first syllable may be cognate to the ethnonym Mansi, which in the Mansi language (манси mańśi) means simply 'man, Mansi'. The (Ob-)Ugric word has been proposed to be an old Indo-Iranian loan (cf. Sanskrit mānuṣa, Avestan manuš "man, male").

The external name Hungarian was recorded in the 13th century by Anonymous in the Gesta Hungarorum, as originating in the 9th century from the castle Ung (Hungu) now in Slovakia.[5]

Et uocatus est arpad dux hungarie et ab hungu omnes sui milites uocatj sunt hunguarie...

‘And Arpad was called duke of Hungarie from Hungu and his warriors were called Hunguarians...’

Later the Italians began using the phrase Hungarorum which first appears in the Song of the Watchmen of Modena in 924 AD.

A sagittis Hungarorum libera nos Domine!

‘From the arrows of the Hungarians, O Lord deliver us!’

This may be a play on words taking the similarity of the word hunguarie to the name of the Huns, as Hungarorum could be divided "hun-garorum": garorum is plural for garum which was an Italian sauce made from fermented fish intestines. It is the phrase Hungarorum and not hunguarie which then became the accepted term to refer to Hungarians as the title of the Hungarian chronicle Gesta Hungarorum attests to. Anonymous also uses the singular form of the fish sauce reference in his prologue as the word Hungarum, "Incipit prologus in gesta hungarum".

The Hungarians also came into contact with the Khazars. After the Khazar empire collapsed, Magyars lived as an independent nation, moving westward. In 895–896, under the rulership of Prince Árpád, they crossed the Carpathian Mountains, and settled the area of present-day Hungary. They also began to establish their own state here, namely the Principality of Hungary.

Early loanwords

There are some really early loanwords in Hungarian, which enriched the language's vocabulary, estimated to 25,000 words at the time. Here are some examples:

| Origin | ||

|---|---|---|

| Iranian | arany 'gold', szarv 'horn', száz 'hundred'[6] | ezer 'thousand', híd 'bridge', réz 'copper', sajt 'cheese', tej 'milk', tíz 'ten', zöld 'green'[7] |

| Turkic | hattyú 'swan', szó 'word', hód 'beaver' | homok 'sand', harang 'bell', ér 'worth sth' |

| Permic | agyar 'fang', daru 'crane', hagyma 'bulb' |

In the era of the Turkic influences, Hungarians developed especially culturally: the borrowed vocabulary consists of terms referring to sophisticated dressing, and the words of a learned upper class society. The phrases of basic literacy are also of Turkic origin. A number of words related to agriculture and viticulture have the same background.

Phonetics

Vowels

| Hungarian | Finnish | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| hal | kala | fish |

| kő; köv- | kivi | stone |

| lúd | lintu | hu: goose, fi:bird |

| kéz | käsi | hand |

The phonetic system of Hungarian went through large changes in the Old Hungarian period. The most important change was the disappearance of the original Uralic word-ending vowels, which eroded in many descendant languages (among others Finnish, however, largely preserves these sounds; see the table on the right). Even so, declined forms of the nouns and inflected verbs of Uralic origin still show traces of the lost sounds: ló (horse)—lovas (rider); kő (stone)—köves (stony). This was the process of phonetic reduction. The earliest written records of Hungarian from the 9th century still show some retained word-final vowels, e.g. in hodu 'army' > modern had.

Possibly there had been also present a velar ï sound as well, later replaced by a palatal i. Today, since Hungarian has vowel harmony, some words containing the palatal sound i pick up the back suffix when conjugated or declined—instead of the front suffix, which is usual for i's of other origin. Some examples: nyíl (arrow) → nyilat (accusative; instead of *nyilet); inni ([v inf], to drink) → ivás (drinking [n], instead of *ivés).

The transition from diphthongs to simple vowels had already begun in the Proto-Hungarian period.

Consonants

Plosives between vowels developed to spirants, and those after nasal stops became voiced:

| Original Uralic | Replaced by | Position | ||

| p | → | f | (voiceless labiodental fricative) | initial |

| → | β | (voiced bilabial fricative) | medial | |

| t | → | z | (voiced alveolar fricative) | medial |

| k | → | x | (voiceless velar fricative) | in initial position in words that contain only velar vowels |

| → | ɣ | (voiced velar fricative) | medial | |

| mp | → | b | (voiced bilabial stop) | everywhere |

| nt | → | d | (voiced alveolar stop) | everywhere |

| ŋk | → | ɡ | (voiced velar stop) | everywhere |

Grammar

The language developed its interesting features, the transitive and intransitive verb conjugations. (See Hungarian grammar (verbs).) Marked possessive relations appeared. The accusative marker -t was developed, as well as many verb tenses.

Old Hungarian (10th to 15th centuries)

| Old Hungarian | |

|---|---|

| Region | Medieval Hungary |

| Extinct | developed into Early Modern Hungarian by the 16th century |

Uralic

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ohu |

ohu | |

| Glottolog | None |

By the 10th century, the Hungarians had established a principality in present-day Hungary and its neighbourhood. In 1000, Vajk — the later Stephen I of Hungary — got his crown from the Papal State, and the history of the Christian Kingdom of Hungary began.

In the 1490s, Hungarian was spoken by about 3.2 million people; this number was fairly high at the time. The first examples of official and legal use are dated back to these years. Some personal letters and wills are known. Nevertheless, the Ottoman Empire put pressure on neighbouring nations, just like on Hungary—the latter was unstable at the time, due to internal lordship debates. This led to the Hungarian (led by Louis II of Hungary) loss of the Battle of Mohács (1526). In 1541, Ottomans finally captured the capital, Buda as well. The country was split up to three parts; the southern regions fell under Ottoman rule; the western parts officially remained "Kingdom of Hungary", with Habsburg kings; and the eastern area, mainly Transylvania and the Partium became independent. Historical linguists set the end of the Old Hungarian period at 1526, as it is a such important date in Hungarian history.

Literary records

The Latin language was made official in the country—especially in the 11th to 15th centuries, the language of literature and religion was Latin. However, Hungarian was used in certain cases; sometimes it was fitted into Latin documents, to avoid later disputes about proprietary rights.

However, the first official document of Hungary is not in Latin, but in Greek—this is the "Charter of the nuns of Veszprémvölgy",[8] dated to 997. The text contains some Hungarian (and also some Slavic) place names: e.g. saɣarbrien (compound formed from saɣar 'shaft' + an obsolete Turkic loanword, brien 'coalition'—today Szárberény); saːmtaɣ 'plough'; meleɡdi (from meleg 'warm' + -di diminutive suffix).

The next most important document is the "Establishing charter of the abbey of Tihany", dated to 1055. In the Latin text, 3 Hungarian sentences, 58 words, and 33 suffixes are present. The longest sentence is, in the original spelling, feheruuaru rea meneh hodu utu rea (reconstructed pronunciation: /fɛhɛːrvaːru reaː mɛnɛɣ hɔdu utu reaː/; modern Hungarian: "Fehérvárra menő hadi útra"—the postposition "rea", meaning "onto", became the suffix "-ra/-re"—English: 'up to the military road going to Fehérvár'). Today, the vellum is kept in the abbey of Pannonhalma.

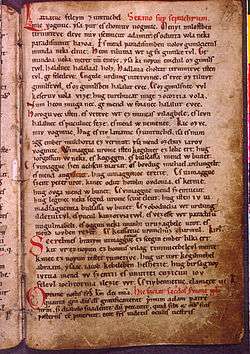

Skipping intermediate Hungarian relics, the next important point is the "Funeral Sermon and Prayer" from 1192. This is the first text completely in Hungarian. The document is found on the 154th page of the Codex Pray (Pray here is not English; it is a name). The sermon begins with the words Latiatuc feleym zumtuchel mic vogmuc. yſa pur eſ chomuv uogmuc (/laːtjaːtuk fɛlɛim symtyxːɛl mik vɔɟmuk iʃaː por eʃ xɔmou vɔɟmuk/ — "Do you see, my friends, what we are: truly, we are only dust and ash.")

Literature in Hungarian is counted since the previous writing. The first known Hungarian poem has the title 'Laments of Mary'—its theme is the story of Jesus' crucifixion, from the viewpoint of Mary. It was denoted around 1300, but possibly it is not the first version. Its text is clear, easy to understand and logical, free of latinisms. The first verse:

|

vɔlɛːk ʃirɔlm tudɔtlɔn |

I was lament-ignorant; |

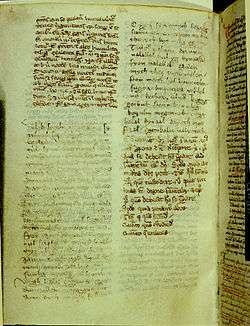

The next important relic—with a cheerless history—is the "Fragment of Königsberg", dated approximately to the 1350s. This is the remains of the first known, explicitly proven Hungarian book. The codex had arrived at Wrocław, Poland, by the end of the century; there, because it was not understandable to the Polish bookbinder, it was chopped and used to bind a Latin book. The other important book from the time is the Codex Jókay; a 15th-century copy of an original from 1372. The codex is about the life of Francis of Assisi.

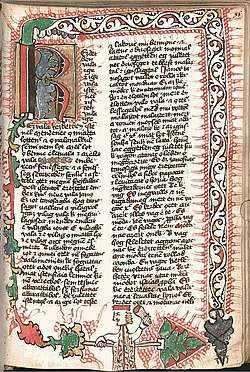

In the early 15th century, some non-comprehensive Latin-Hungarian dictionaries, or rather word lists, were composed. Some shorter texts are also known. The most important work is however the first translation of the Bible: the Hussite Bible, dated to 1430. The Bible was translated by priests Tamás Pécsi and Bálint Ujlaki. They were affected by the concepts of Jan Hus during their university years (1399–1411) in Prague. The Inquisition pursued these concepts, and the translation was confiscated from the translators; regardless it became so popular that several authentic copies of the original survive.

More and more Hungarian books were written, most of them religious. Over and above the "Laments of Mary", the other important item of Old Hungarian poetry is Szabács viadala ("Triumph of Šabac"). Reputedly it was denoted in the year of the battle (1476); in this, Hungarian troops led by King Matthias of Hungary had a glorious victory over the Ottoman army—its issue is secular. It is possibly a fragment of a longer poem. A quotation:

|

dɛ ɑz feʎːøːl mondot paːl keneʒi |

But, Pál Kinizsi said about the thing, |

Some Old Hungarian script inscriptions are also known, such as the "Alphabet of Nikolsburg" (1483) and a number of deciphered and undeciphered inscriptions.

Linguistic changes

Vocabulary

In this period, Hungarian developed several new words. One way this happened was through loanwords coming from languages whose speakers mediated the new concepts. On the other hand, internal word formation also took place, in which the words for new concepts were derived from earlier words.

Compared to Modern Hungarian, Old Hungarian was rich in derivative suffixes. Most of these suffixes are also derived from other suffixes, so they can be aligned in "suffix-bushes". There were numerous diminutive suffixes, non-productive in today's Hungarian, e.g. -d ("holmod", from "holom"—"tiny hill"); -t (it left its trace in some geographic names) -n, -ny, -m (as in kicsiny, from kicsi—very little).

Forming compounds was also a way to coin new terms.

But then again, there are several loanwords dating back to the period 896–1526. Loans were mainly acquired from Slavic languages (for example, kiraːʎ 'king'), German (e. g. hɛrtsɛɡ 'prince'), and Latin (e. g., tɛmplom 'church'). As emerges from the previous examples, these words are primarily associated with Christianity and politics. Other loans are the names of animals living outside Hungary, terms of technology, and so on.

Grammar

- Verbs

Like English, Modern Hungarian has two verb tenses: past and nonpast. Futurity is expressed using the auxiliary verb foɡ. However, Old Hungarian had six verb tenses: Past Narrative (Latin: praeteritum), Past Finite, Past Complex, Present, Future Simple, and Future Complex.

Past Narrative was marked using the suffixes -é, -á in transitive and -e, -a in intransitive. The tense was used to describe an array of past events originally. The verb várni 'to wait' conjugated in this tense:

| Past Narrative - várni | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Person | Type | |

| Transitive | Intransitive | ||

| Singular | 1st (I) | várám | várék |

| 2nd (You) | várád | várál | |

| 3rd (He/She) | várá | vára | |

| Plural | 1st (We) | várók | váránk |

| 2nd (You) | várátok | várátok | |

| 3rd (They) | várák | várának | |

Future simple was expressed using the suffix -nd.[9] Future complex (the present-day future tense of the language) is conjugated in the following way:

- Infinitive + auxiliary verb 'fog'

- menni fog—he/she is going to go

- See also: Hungarian grammar (verbs).

Middle Hungarian

The first printed book written in Hungarian was published in Kraków in 1533, by Benedek Komjáti. The work's title is Az Szent Pál levelei magyar nyelven (In original spelling: Az zenth Paal leueley magyar nyeluen), i.e. The letters of Saint Paul in the Hungarian language. In the 17th century, the language was already very similar to its present-day form, although two of the past tenses were still used. German, Italian and French loans also appeared in the language by these years. Further Turkish words were borrowed during the Ottoman occupation of much of Hungary between 1541 and 1699.

Linguistic changes

The vowel system of Hungarian had developed roughly to its current shape by the 16th century. At its fullest the system included eight phonemes occurring both short and long:[10]

| Front | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Illabial | Labial | ||

| Close | i, iː | y, yː | u, uː |

| Mid | e, eː | ø, øː | o, oː |

| Open / Open-mid |

ɛ, ɛː | ɔ, aː | |

This largely symmetric system was complicated only by the presence of open illabial /aː/ as the long counterpart of short /ɔ/. In modern Hungarian this is mainly found as a front vowel.

The contrasts between mid /e/ and open-mid /ɛ/ (including their long counterparts) have later been mostly lost. The shift /ɛː/ > /eː/ took place widely during the 16th and 17th centuries, across most of the Hungarian-speaking area. In several dialects this however did not lead to a merger; in response, /eː/ may have been either raised to /iː/, or (in northeastern dialects) diphthongized to /ie/. The shift /e/ > /ɛ/ also arose equally early in the central dialects underlying Standard Hungarian. Its spread to the other Hungarian dialects has however been much slower, though the emergence of widespread literacy and mass media in the 20th century has supported its continuing adoption.

Modern Hungarian

In the late 18th century, the language was incapable of clearly expressing scientific concepts, and several writers found the vocabulary a bit scant for literary purposes. Thus, a group of writers, most notably Ferenc Kazinczy, began to compensate for these imperfections. Some words were shortened (győzedelem > győzelem, 'triumph' or 'victory'); a number of dialectal words spread nationally (e. g. cselleng 'dawdle'); extinct words were reintroduced (dísz 'décor'); a wide range of expressions were coined using the various derivative suffixes; and some other, less frequently used methods of expanding the language were utilized. This movement was called the 'language reform' (Hungarian: nyelvújítás, lit. "language renewal"), and produced more than ten thousand words, many of which are used actively today. The reforms led to the installment of Hungarian as the official language over Latin in the multiethnic country in 1844.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw further standardization of the language, and differences between the already mutually comprehensible dialects gradually lessened. In 1920, by signing the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost 71% of its territories, and along with these, 33% of the ethnic Hungarian population. Today, the language is official in Hungary, and regionally also in Romania, Slovakia, and Serbia.

Old Hungarian text sample

Hungarian

Latiatuc feleym zumtuchel mic vogmuc. yſa pur eſ chomuv uogmuc. Menyi miloſtben terumteve eleve miv iſemucut adamut. eſ odutta vola neki paradiſumut hazoa. Eſ mend paradiſumben uolov gimilcictul munda neki elnie. Heon tilutoa wt ig fa gimilce tvl. Ge mundoa neki meret nu eneyc. yſa ki nopun emdul oz gimilſtwl. halalnec halalaal holz. Hadlaua choltat terumteve iſtentul. ge feledeve. Engede urdung intetvinec. eſ evec oz tiluvt gimilſtwl. es oz gimilſben halalut evec. Eſ oz gimilſnek vvl keſeruv uola vize. hug turchucat mige zocoztia vola. Num heon muga nec. ge mend w foianec halalut evec. Horogu vec iſten. eſ veteve wt ez munkaſ vilagbele. eſ levn halalnec eſ poculnec feze. eſ mend w nemenec. Kic ozvc. miv vogmuc.

English

Ye see, my brethren, with your eyes, what we are! Behold, we are dust and ashes. Through His divine grace the Lord God first made our ancestor, Adam, and gave him the Paradise of Eden for his home. And of all the fruits of Paradise, He bade him live, forbidding to him only the fruit of one tree, yet telling him, why he should not eat of it: "Lo, on the day thou eatest of this fruit, thou shalt die the death of deaths." Adam had heard of his death from his Creator-God, yet he forgot. He yielded to the Devil’s allurement, and ate of the forbidden fruit, and in that fruit he partook of death. And so bitter was the juice of that fruit, it (almost?) burst their throats. Not only for himself, but for all his race he ate death. In anger, God cast him into this world of toil, and he became the nest of death and damnation, for all his kind. Who shalt be those? We are them.—Quoted from the Funeral Sermon and Prayer, 1192.

See also

- Hungarian language

- Hungarian dialects

- Hungarian literature

- Funeral Sermon and Prayer

- Old Hungarian 'Lamentations of Mary'

- History of Hungary

- Alternative theories of Hungarian language origins

Notes

- The speakers of the Uralic languages are not related genetically, only linguistically.

- An obsolete word. The word tat in modern Hungarian means 'stern'.

- Jó no longer means river in Hungarian; instead, the term folyó is used, derived from the verb folyni 'flow'. However, certain geographic names in Hungary prove the existence of the word jó: Berettyó (from Berek-jó 'Grove-river'), Sajó (from Só-jó) etc. Also compare Finnish joki 'river'.

- Mony is also unknown in Modern Hungarian.

- https://la.wikisource.org/wiki/Gesta_Hungarorum

- These words have cognates also in the Finno-Permic languages and they may as well have been loaned earlier from Proto-Indo-Iranian.

- Berta & Róna-Tas 2011, pp. 1331–1339

- "Veszprémvölgy" is a place name, around present-day Veszprém.

- Traces of future simple are still found in the language. The future suffix, -nd, is an element of the suffix -andó/-endő, used to derive a kind of participles. Example: elintézendő 'something that has to be administered in future'.

- Kálmán 1972, 67–68

Reference works

- Balázs, Géza: The Story of Hungarian. A Guide to the Language. Transl. by Thomas J. DeKornfeld. Budapest: Corvina Publishing, 1997. ISBN 9631343626

- Berta, Arpád & Róna-Tas, András: West Old Turkic: Turkic Loanwords in Hungarian (Turcologica 84). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2011.

- Kálmán, Béla: Hungarian historical phonology. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1972.

- Molnár, József—Simon, Györgyi: Magyar nyelvemlékek. 3rd edition, Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó, 1980. ISBN 9631747387

- Dr. Inczefi, Géza: A magyar nyelv fejlődéstörténete. Typescript. Budapest: Tankönyvkiadó, 1969.

- Heltai, Gáspár: Száz fabvla. Kolozsvár: Heltai Press, 1566.

- Lakó, György: Proto-Finno-Ugric sources of the Hungarian phonetic stock (Uralic and Altaic series 80). Indiana University Press, 1968.

- A magyar középkor története. Pannonica, 2006.

- Papp, István: Unkarin kielen historia (Tietolipas 54). Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura, 1968. OCLC 23570356 ISBN 978-951-717-012-3

- Ruffy, Péter: Bujdosó nyelvemlékeink. Budapest: Móra Publishing, 1977.