Munnar

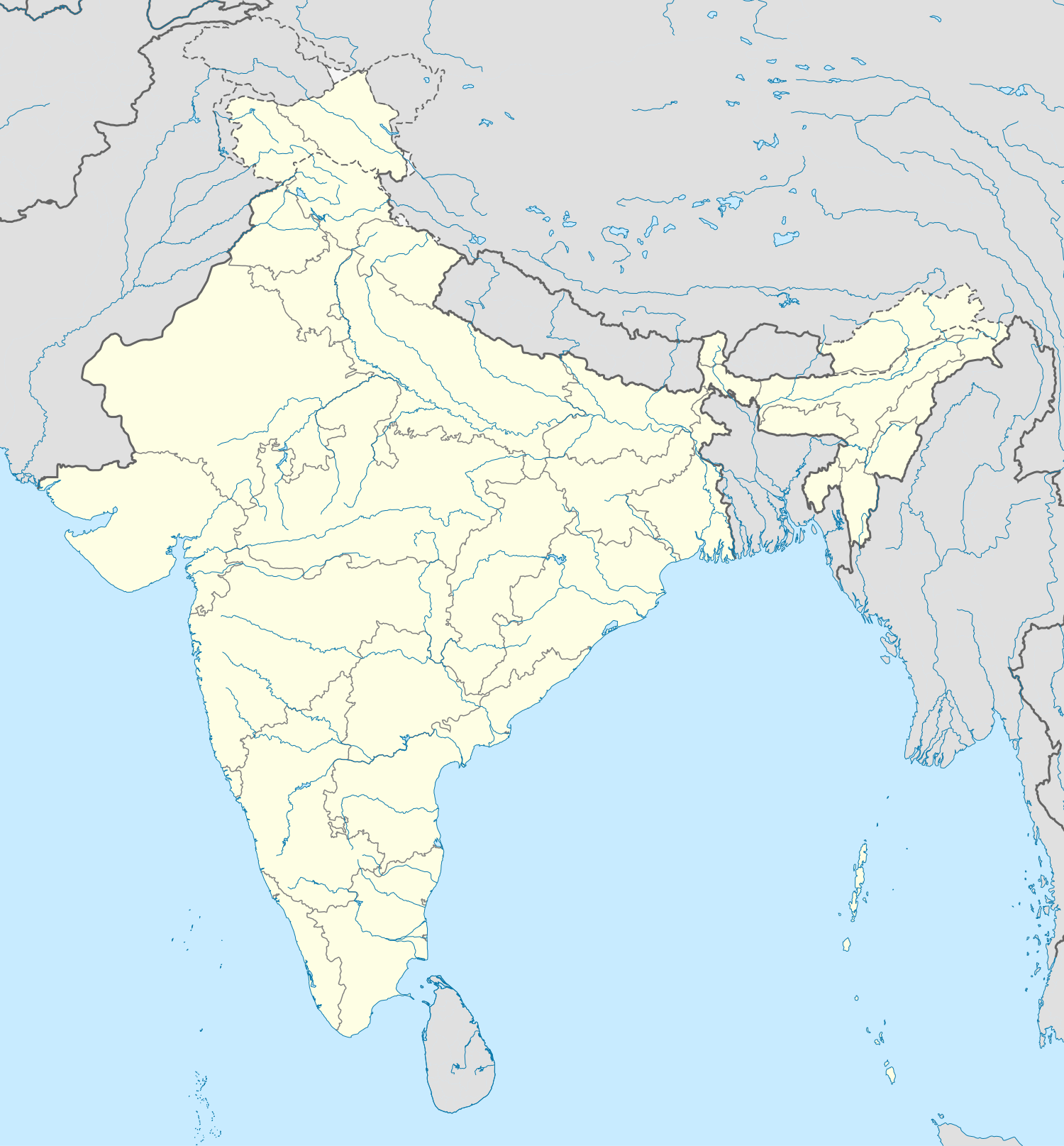

Munnar is a town and hill station located in the Idukki district of the southwestern Indian state of Kerala. Munnar is situated at around 1,600 metres (5,200 ft) above mean sea level,[2] in the Western Ghats mountain range. Munnar is also called the "Kashmir of South India" and is a popular honeymoon destination.

Munnar | |

|---|---|

.jpg) A view of Munnar | |

| Nickname(s): The Kashmir of South India | |

Munnar  Munnar | |

| Coordinates: 10°05′21″N 77°03′35″E | |

| Country | India |

| State | Kerala |

| District | Idukki |

| Named for | Tea plantations, cool climate |

| Government | |

| • Type | Panchayath |

| • Body | Munnar grama panchayath |

| Area | |

| • Total | 187 km2 (72 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,532 m (5,026 ft) |

| Population (2001) | |

| • Total | 38,471 |

| • Density | 210/km2 (530/sq mi) |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Malayalam, English |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 685612 |

| Telephone code | 04865 |

| Vehicle registration | KL-68, KL-06 |

| Literacy | 76% |

| Website | keralatourism |

|

History[3]

The tradition that Col Arthur Wellesley, later to be the Duke of Wellington, leading a British detachment from Vandiperiyar to Bodinayakanur, then over the High Range and into the Coimbatore plains to cut off Tippu Sultan's retreat from Travancore, was the first Englishman in the High Range appears to be belied by the dates involved. If the story is a dozen years too early for Wellesley, it is quite possible that some other officer in General Meadow's Army may have had that distinction. Unfortunately, no record of that pioneering mountain crossing has been traced. What is available is a record of the surveying of this terrain in 1816-17 by Lt Benjamin Swayne Ward, son of Col Francis Swayne Ward to whom we owe many of the early views of Madras and South India Now available in lithprints.

Ward and his assistant Lt Eyre Connor were on orders to map the unexplored country between Cochin and Madurai and so they followed the Periyar into the mountains and then headed north into what at that time was described as "the dark impenetrable forests of the High Range". They lost men to at least one elephant charge, suffered agony from leech bites and once ran so short of food that a deer run down and being feasted on by wild dogs was manna for the party and their jungle guides. The subsequent report by Ward and Connor was to lead to the Periyar Dam project, completed only in the 1890s,but for the present they were more pre occupied getting into the mountains that they could see towering in the distance from Bodi. Then, on 14 October 1817, "the weather having improved the ascent into the High Range began".

Their first major camp was at a flat promontory at 6000 feet. And this was ever afterwards to be known as Top Station. Moving north, they saw to their south the Cardamom Hills, a slope 45 miles long and 30 wide from the heights above Bodi stretching into Travancore. To their north there appeared to be grasslands on high rock peaks. And in front of them, "an outstanding mountain, shaped like an elephant’s head". On 8 November, they established camp at the confluence of three rivers, which they judged to be the centre of the district, and from Munnar ("Moonar – three rivers), as it came to be known, they surveyed the area, discovered the ancient village of Neramangalam in ruins but surmised that it might well have been from here that ivory and peacock feathers, pepper and cardamom, sandalwood and other timber went to the lands to the West across the Arabian Sea".

It was to be nearly 50 years later that Sir Charles Trevelyan, Governor of Madras, instructed Col Douglas Hamilton to explore the hill country in the western part of the Madras Presidency, requesting special advice on the feasibility of establishing sanatoria for the British in the South and of developing revenue- earning projects without endangering the environment, as had happened in Ceylon where coffee had destroyed not only the rain forest but also paddy cultivation in the north – central rice bowl of ancient Ceylon.

Marching south along the Anamallai, Hamilton saw "the grandest and most extensive (view) I have ever beheld; some of the precipices are of stupendous magnitude and the charming variety of scenery comprising undulating grassy hills, wooded valleys, rocky crags, overhanging precipices, the green rice fields far below in the valley of the Anchanad, the grand mass of the Pulunies (beyond) and the blue ranges in the far distance, present a view far beyond my power to describe…"

On 7 May 1862, Hamilton set out to climb Anaimudi, following a "well worn elephant path, ascending the opposite slope by a series of short zigzags that were so perfect and regular that we could scarcely Eravikulam plateau (later Hamilton’s Plateau), watered by two streams, one of which bordered the Eravikulam swamp before cascading down 1000 feet in a beautiful waterfall. Separating the plateau from Anaimudi was a deep, thickly forested ravine – later called Inaccessible Valley and, detouring it, they began the climb from the east to the peak. On our return, we followed an elephant path for several miles, the gradient of this path was truly wonderful, these sagacious animals avoiding every steep or difficult ascent, except at one hill which was cleverly zigzagged, owing to masses of sheer rock preventing a regular incline being taken."

It was to be 15 years later before another report came in. But this was more significant from the viewpoint of this history, for though it came as a result of the shikar expeditions of the ever-exploring John Daniel Munro, he was an opener – up of land and a pioneering planter first and a shikari second. Reporting on the High Range in 1877, he wrote, "Exclusive of the low Unjenaad valley which is not above 3100 feet, the area within these boundaries may be roughly estimated at 200 square miles with an elevation over 5000 ft … Much of this is worthless land, but there is a good deal fit for cultivation … Coffee … would succeed well at a somewhat lower elevation, and Tea and Cinchona would grow miles available for these purposes, and there being the great inducement of a good climate, it will doubtless not be many years before these fine hills get occupied".

And Munro, who always had a long – range view of things, indeed proved right again. Mention has already been made of the journey into these hills by Henry Turner and his half – brother ‘Thambi’ A W Turner, the concessions that Munro, then Superintendent of the Cardamom Hills for the Raja of Travancore, got them from the Raja, and the Society the three of them formed in 1879 with Rs 450,000 capital. The agreement they entered into with the Rajah read in part: "The annual sum of one half British rupee on every acre of land other than grassland comprised in such deed which has already been or shall hereafter from time to time be opened up for the purpose of cultivation or otherwise".

While Thambi Turner began in 1879 clearing the forest round the Devikulam camp, later to become the taluk headquarters, Henry returned to Madras and began looking for others willing to take up land here. The first to do so was Baron George Otto Von Rosenberg of Dresden and his sister who were kin of the Turners by marriage. The Baron opened up Manalle, later a part of the family's Lockhart Estate, and it was developed by his son Baron John Michael in the 1890s, the first tennis court in the hills being added. It was property that was to remain for years in the family. Then came A H Sharp, who opened up Parvathi in the wilds and planted the first tea, to be followed by C Donovan. In1881 came E J Fowler to open up Aneimudi Estate and in 1882, C O Master and G W Claridge, C W W Martin, a fellow of Henry Turner's in the Madras Civil Service, sent his 18 – year – old nephew Aylmer Ffoulke Martin (Toby) to open Sothuparai near Chittavurrai in 1883 and Toby Martin ever seemed to be clearing new land for others after that. Other estates of this era were H M Knight's Surianalle, Panniar belonging to J A Hunter and K E Nicoll and the Turners’ Talliar where the last coffee in the High Range flourished on 700 acres. Every one of them benefited from the experience of Ceylon planter John Payne, whom Henry Turner ‘imported’ in 1881. Payne not only opened up Talliar with coffee for the Turners, but he taught his fellow planters in the High Range road tracing, draining and general thottam work. He also cut a riding road, Payne's Ghat, from Devikulam to Periakanal and opened the district up to ‘civilisation’.

In the Eighties, it was only their indomitable will that kept the planters going in this wilderness. They lived in grass – thatched huts with mud and wattle walls and surrounded their homes with elephant trenches. The only medical aid each planter had was "his own medicine chest and he had to doctor himself and his coolies with only Doctor Short’s old book on Medicine in India to help him". It was 1889 before the pioneers saw the first European woman in the hills. That was when Baron Otto brought up his wife, the daughter of Henry Gribble of the Madras Civil Service; another Gribble girl married one of the Turner brothers. And in 1890 Toby Martin brought his bride – and they were to live decades in these hills.

An event which helped considerably to improve the lives of the early planters was when Claridge and Toby Martin descended from Top Station to Bottom Station (Koranganie at the head of the Bodi Pass) and went on to Bodinayakanur. There they met Suppan Chetty, who appeared to be the village leader, and negotiated him to send up rice and other provisions by headload and bring down cinchona bark and other products for onward transport. Soon bullocks, donkeys and ponies were brought in to help. This link with Suppan Chetty and his adopted son Alaganan Chetty, later an M L A, was to continue into recent times with their successors, M/s A S Alaganan Chetty & Sons.

Another event of significance was the arrival of John Ajoo, A Chinese, at Talliar Estate. One of six Chinese brought out by the East India Company to advice on tea planting and manufacture in the Nilgiris, he was recruited by Henry Turner and sent to the High Range. A small field of tea around the Munnar Estate Manager's bungalow was once 13 acres in extent and used to be called ‘Chinaman’s Field’. John Ajoo's son Antony later owned a small estate called Vialkadavu next to Talliar in which the Turner family long retained an interest.

By 1894, 26 estates, all of them small – holdings, were functioning on the Society's lands but none was doing well as the cinchona boom began to go bust. The Society, by now, was in financial difficulties and it advertised its land widely in British and Indian newspapers. One of the first to respond was the North and South Sylhet Company, a subsidiary of Finlay Muir, arrived in India in December 1894 to finalise the transaction, then decided to visit the High Range with his son James and P R Buchanan and W Milne (from Ceylon). Accompanying them was H M Knight, a pioneer in the Anamallais and at the time a prominent proprietary planter. James Muir's record of that journey from 17 December 1894 till 5 January 1895 is not without interest, revealing as it does the conditions of the times. It reads in excerpts:

…arrived at Madras on the morning of the 12th December … next few days were occupied in negotiations regarding the purchase of the shares of the … Society …and Rs 69/- per share was the price arranged to be paid after deductions for losses and money spent during the year ended 30 November 1894…

… We arrived at Ammayanayakanur at 11:30 am the train being 23 minutes late, and … had dinner at 6 pm and about 7’o clock started in the bullock transit – there being four of these carts altogether – to do some 40 miles, to a village called Tayne(Theni). The bullock transits, and the carriage of all stores to Bodynaikanur , are managed by the United Carrying Company and one has to write the agent of this company at Ammayanayakanur for all that may be required.

After a not very comfortable night in these wagons we arrived at Tayne … We started for Bodynaikanur – Sir John being carried in a chairpart of the way … In the bullock transits mattresses are necessary and indeed one wants as much as possible under one, so as to break the jolting of the carts. We got away from Tayne shortly after 7, and reached Bodynaikanur about half past ten. The distance is supposed to be only some nine miles, but the bullock carts which carried our things went slowly, and Sir John, being carried part of the way in a chair, also caused delay. A large chair had been specially prepared in Madras, but when we arrived at Tayne we could not find what had become of it, and there was a small one there, which Mr Brown had sent back from Bodynaikanur. On arrival at Body we were advised not to stop long there, but to push on to Mettor the same day as there as severe cholera at Bodi and in the surrounding country … We found the chair which had been sent from Madras at Bodi and it was sent off with 10 carrying coolies, about one O’ clock, to go three miles along the road to Mettor and to wait there. The weight of the chair was 140 pounds , and the coolies had to be promised extra money when they got to Devikulam to induce them to go. Thirty – two coolies went with us from Bodi in addition to the 10 chair coolies, but the larger number of these were required for stores and parts of the tents which had not been already sent on. The bungalow at Bodi … (had a) very obliging (man who was) a fair cook. (We were very sorry to learn that he has since died of cholera, so that it was most fortunate we hurried on to Mettor, as Mrs Knight and Mr Graham who were only a short time at the bungalow also caught cholera and the former died.) … As the road was bad and steep the bearers made but little progress, (so Sir John) left the chair …riding the rest of the way to Mettor … The distance from Bodi to the foot of the ghaut is about 3 miles, the rest of the way being all an ascent and the road a very poor one, even for pack ponies, and would require a great deal of money to be spent on it would be passable for carts ….

The chair coolies were started off … to go 5 miles along the road to Devikulam … The road … would require a great deal to be done to it before it could be fit for bullock cart traffic … We walked and rode in turn till we got to Devikulam… the distance between Mettor and Devikulam is about 14 ½ miles… At Devikulam … went over the map of the Society’s land with the Baron…

…(at) Mr Grigg’s Camp … Sir John and Mr Milne had numerous conversations with Mr Grigg as to roads, the prompt opening out of the property and other matters connected herewith. Mr Grigg strongly advised that a main road should immediately be made through the centre of the property, that it should be constructed economically, and a careful statement kept of the outlay in connection with it, and he undertook to recover the amount from the Travancore Sircar to continue the road to the West from the Society’s boundary to Cochin which he thought would be the best Shipping Port for the Society’s produce … He also thought the alignment of the proposed railway might be so altered as to enable the traffic between Cochin and the Society’s estate to be carried on this line to advantage part of the way … Sir John inquired if Mr Grigg would like to have a piece of land specially made over to him so that he might arrange for an additional house being erected, thereon, for the accommodation of the resident as a health resort. Mr Grigg replied he would very much like to have a suitable site for this purpose not far from where his camp was erected, and a cross was made on the map then, before Sir John, and Mr Grigg indicating the spot, and Sir John undertook to request the directors of the North and the South Sylhet Tea Companies to make a gift of whatever land Mr Grigg, after further consideration, might select for this purpose…

The soil in the forest is deep and rich, and the river can be utilized to drive a large quantity of machinery. A beginning should be made here with both Tea and Coffee as soon as the requisite labour can be obtained. The forest is much infested with leeches and precautions had to be taken against them…

It is proposed not to decide where to put coffee until the jungle is all burned off, so as the area that will be put into tea and the area that will be put into coffee is not yet fixed.

1 January 1895

It was arranged that Mr Payne should give part of his time to the society to be spent first of all in selecting suitable coffee land inside or outside of the society’s boundaries, and that afterwards he should superintend and be entirely responsible for all the work thereon. For this it was arranged that he should receive a salary of Rs 3000/- per annum, for the present, to be paid monthly. Mr A Ff Martin, presently managing Sothuparai was, with Mr Payne’s approval, selected to be his first assistant with this work, and it was arranged that Mr Martin should receive a salary of Rs 100/- per month for his partial services as from 1 January 1895, and until the date when he should come over entirely to the service of the society, from which date his salary was to be Rs 300/- per month, for two years and after that Rs 350/- per month, for one year, always provided he gave entire satisfaction to Mr Payne, under whose orders he was to be. This arrangement however was not to come into force until Mr. Martin had cleared himself to Mr Payne’s satisfaction of the charges brought against him by Mr James Turner.

The road … from Marioor to Chinnar, is just about as bad as could be imagined, and, in many places, is not unlike the rocky bed of a mountain stream … it being impossible to ride – the horses having to be guided with great care by the syces, but at the end of 3 miles we came to a level road and here we found 3 bullock gharries … waiting for us … Sir John lay down in one of them and the other two were loaded with the baggage… The first 4 miles or so of the road that we had to do to Oodamullapet, our destination, were very bad and heavy with sand, and we made very slow progress, but after that we got on to an excellent road …"

H M Knight was appointed the first General Manager, but with his new bride having just died, he was making plans to leave the country. Nevertheless, opening up of the jungle continued under Payne and with other experienced planters brought in from Ceylon. And A Suppan Chetty’s Pankajam Company at the foot of the ghats. In 1897, the Kannan Devan Hills produce company was registered as a separate company with a capital of 1.5 million and together with, a few years later, the American Direct Tea Trading Company Ltd., another member of the Finlay Group, became holders of almost the entire concession, except for a few estates first planted in the lower reaches by the pioneers. They owned 26 Estates, a few with coffee, most with cinchona.

With a growing work force and increasing hills produce, Willie Milne, who had been brought back from Ceylon to become the second General Manager, raised with Toby Martin’s help a herd of 500 bullocks to ensure transport up and down the ghat. ‘ Bullocky Bill’ Lee was put in charge of the cattle farm on the Kundale flats which was tended by vets brought out from England. Communication between estates was by runner and the planters kept horses on the estate for their use – and their wives’. Mrs Toby Martin remembered years later, " The rivers were mostly unbridged; so it was quite the thing to dash into them with water up to the girths, hoping to get over fairly dry. The monsoon put great tests on everybody, but then everybody was able to ride well"

When Milne left for Ceylon in 1899, H Leybourne Davidson became General Manager and transport and communications continued to be a priority, even as more acres were opened and it became certain that tea was to be the main crop. He established telephone communication between all estates. Once it was determined that the Kundale Valley, from Munnar to Chittavurrai Estate and Top Station, was the proper dividing line of the property on which the main road should be laid to feed the estates on either side, he got work going on the road, contracting it to out to the Gordon brothers , and began planning a ropeway from top station to the start of Kotagudi Ghat, Bottom Station. The rope way was an ingenious construction, 2 ¼ miles in length and dropping 5000 feet, built by Gideon and William Kemle from Periyar Dam scrap. The ropeway was opened in 1900 with great fanfare and provided splendid service for many years. Mrs Martin described it " as a great and wonderful undertaking. The difficulty of combating the very rocky and steep country together with that of preventing wild elephants from pulling down standards and interfering in general with the work, was great for both engineers and workmen. Besides this, the fever … caused suffering to many … Gideon Kemle… died a few years afterwards of (it) …

Once the ropeway was completed, Davidson decided to speed up traffic from Munnar. A monorail trameline was laid from Munnar to Top Station along the road. Large platforms, fitted with one large wheel to run on the road and a smaller wheel to run on a single rail, were drawn by bullocks. Later, ponies, posted at intervals, were used and speeded traffic from about 4 mph to 6 mph. The tea chests were loaded on the platforms and if passengers wanted to use the ‘tram’ two easy chairs were placed on the platform and luggage piled all around them; from Top Station the passengers would have to tolerate the discomfort of bandies to reach Bottom Station and onwards.

A tea chest moved from Kannan Devan to England the Davidson way went through various adventures, which is perhaps why Davidson became Sir Leybourne. The tea chest moved from the estates to munnar by bullock cart, be loaded on to the monorail platform to be moved to Top Station, be transported from there in Suppan Chetty’s bullock carts to Ammayanayakanur railway station, then by train to Tuticorin, and, finally, by lighter to the steamer in the road! P R Buchanan took over as General Manager in 1901 and there began the fastest, most extensive opening up of the High Ranges, virgin jungles being felled, often with armed watchmen providing the workmen protection from the elephants and other wild life. When, in 1908, he started building a 2’ gauge light steam railway to replace the monorail, another link was added in this ingenious transport chain; the train would bring chests up to the point the tracks had been completed, then the goods were headloaded and taken to what was left of the monorail and its platform! The railway was eventually opened for traffic in 1909 and even had 1st and 2nd class accommodation

When Buchunan left in 1911, Kanan Devan had grown to over 11,500 acres, while Anglo – American had over 1500 acres under tea; there were only about 3000 acres held by others, much of which was eventually to be taken over by Malayalam Plantations. Herbert Lloyd Pinches now took over and, taking a cue from the way the ropeway and the pioneering Munnar Factory were powered, he started the Munnar Valley Electric Works, which supplied power to nine factories within a radius of six miles. This was the first electric power supplied for tea manufacture in India. In time, much of the High Range would get its power from the MVEW grid.

By 1924, Pinches had ensured that most of the kanan Devan property had been cleared and developed, though development continued till 1932.That was when disaster struck. ‘The Flood’, already referred to, burst upon the High Range in July, parts of it receiving 195’’ in that month. When a big landslide blocking a road burst, the water gushed into Munnar, flooded the town, damaged the road and destroyed the railtrack. When recovery began, Pinches decided there would be no railway again and decided on a new ropeway, from Munnar to Bodi via Top Station.

The first path of this ropeway, work on which was started in 1925, was in three sections, Top Station to Chittavurrai Estate, from there to Sothuparai and Pattupatty, then the third stretch to Munnar. The 14 ½ mile ropeway, with hangers carrying 400 lb loads, could, at full capacity, carry 25 tons a day. The ropeway, which cost a little over Rs 760,000 was opened on 3 December 1926. In 1930, the old Top Station – Kotagudi ropeway was replaced by a modern roads thrust their way through the hills and motor transport made the slow ropeways outmoded.

As the era of motor transport began to get into its stride, there came World War II followed by the winds of change. How the High Range had grown by then, from about 6000 acres cultivated in 1894 to over 28000 acres in 1952! The changing scene saw the recruitment of Indian planters, Rengaswamy Chetty of the Suppan Chetty family the first Kanan Devan management recruit. But he resigned before long and N S Dhar was recruited. He was to stay with the company over 30 years. In 1964, Finlay’s teamed with Tata’s jointly start to the first instant tea factory in the country and by 1967, with devaluation, Finlay’s began taking a closer look at the new Indian scene. Several European planters, many of them third generation High Rangers, left and, soon, Indian managers outnumbered the expatriates. Then, in 1971, the Kerala Government wanted to ‘resume’ all land in the Kanan Devan Hills that had not been used for plantations. This would have deprived the company of over 18,000 acres of Eucalyptus used for estate fuel, along with hundreds of acres within estate boundaries. Negotiations that went on till 1974 – the successful culmination of which marked the Tata Group’s subsequent involvement with Kerala – led to Government agreeing to leave most of the eucalyptus and all the land within the estates to the company, leaving it with a compact 57,000 acres. And with that the old Kanan Devan concession came to an end.

The former Kunda Valley Railway in Munnar was destroyed by a flood in 1924, but tourism officials are considering reconstructing the railway line to attract tourists.[4]

Etymology

The name Munnar is believed to mean "three rivers",[5] referring to its location at the confluence of the Mudhirapuzha, Nallathanni and Kundaly rivers.[6]

Location

Geographic coordinates of Munnar is 10°05′21″N 77°03′35″E. Munnar town is situated on the Kannan Devan Hills village in Devikulam taluk and is the largest panchayat in the Idukki district covering an area of nearly 557 square kilometres (215 sq mi).

Road

Munnar is well connected by both National highways, state highways and rural roads. The town lies in the Kochi - Dhanushkodi National highway (N.H 49), about 130 km (81 mi) from Cochin, 31 km (19 mi) from Adimali, 85 km (53 mi) from Udumalpettu in Tamil Nadu and 60 km (37 mi) from Neriyamangalam.

Distance from major cities

- from Kochi - Ernakulam - 150 km

Railway

The nearest major railway stations are at Ernakulam and Aluva (approximately 140 kilometres (87 mi) by road). The Nearest Functioning Railway station is at Udumalaipettai.

Airport

The nearest airport is Cochin International Airport, which is 110 kilometres (68 mi) away. The Coimbatore and Madurai airports is 165 kilometres (103 mi) from Munnar.

Administration

The panchayath of Munnar formed in 1961 January 24 is divided into 21 wards for administrative convenience. Coimbatore district lies in the north, Pallivasal in south, Devikulam and Marayoor in east and Mankulam, Kuttampuzha panchayaths in the west.

- Vaguvarai

- Chokkanad

- Iravikulam

- Kannimalai

- Periyavarai

- Munnar colony

- Ikkanagar

- Old Munnar

- Chatta Munnar

- Nallathanni

- Sivanmalai

- Munnar town

- Cholamalai

- Kadalar

- Rajamalai

- Kallar

- Lakkam

- Thalayar

- Lakshmi

- Nadayar

- Moolakkada

Flora and fauna

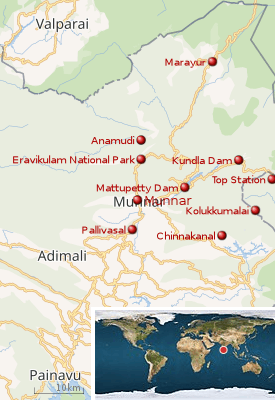

Most of the native flora and fauna of Munnar have disappeared due to severe habitat fragmentation resultant from the creation of the plantations. However, some species continue to survive and thrive in several protected areas nearby, including the new Kurinjimala Sanctuary to the east, the Chinnar Wildlife Sanctuary, Manjampatti Valley and the Amaravati reserve forest of Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary to the north east, the Eravikulam National Park and Anamudi Shola National Park to the north, the Pampadum Shola National Park to the south and the proposed Palani Hills National Park to the east.

Endemic species

These protected areas are especially known for several threatened and endemic species including Nilgiri Thar, the grizzled giant squirrel, the Nilgiri wood-pigeon, elephant, the gaur, the Nilgiri langur, the sambar, and the neelakurinji (that blossoms only once in twelve years). [7][8]

Land ownership

There has been action to address the problems of property takeovers by the land mafia that have, according to successive governments, plagued the area. In 2011, the government estimated that 20,000 hectares of land had been illegally appropriated and launched a campaign of evictions that had first been mooted in 2007.[9]

Things to do in Munnar

There are four major directions in Munnar; Mattupatty Direction, Thekkedy Direction, Adimaly Direction and Coimbatore Direction. The climate and tea plantations are the main reason for tourism in Munnar. Tourists come here to see the plush green carpet that is strewn all around. The tourist count increases every year with a major number during the months of April–May when summer vacations begin across the country. In 2018, a huge number of tourists is expected during the months of August–September when the kurinji blooms once in 12 years.

Mattupatty Direction

- Subramanya Temple, Munnar

- Rose Garden

- Carmelagiri Elephant Park

- Mattupetty Dam

- Cowboy Park

- Kundala Dam

- Top Station

Thekkedy Direction

- Signal Point View Point

- Idly Hill View Point

- Only Organic

- Devikulam Sri Ayyappan Temple

- Lockhart Tea Museum

- Lockhart Tea Park

- Thankaiah Cave

- Lockhart Gap View Point

- Periyakanal Water Falls

- Anayirangal Dam / Boating

Adimaly Direction

- Pothamedu View Point

- Spices Plantation Visit

- Cheeyapara Water Falls

- Chengulam Dam

Coimbatore Direction

- Eravikulam National Park

- Anamudi Peak

- Marayur Sandle Forest

- Lakkan Water Falls

- Muniyara

Other Direction

- Munnar Tea Museum

Geography and climate

The region in and around Munnar varies in height from 1,450 meters (4,760 ft) to 2,695 meters (8,842 ft) above mean sea level. The temperature ranges between 5 °C (41 °F) and 25 °C (77 °F) in winter and 15 °C (59 °F) and 25 °C (77 °F) in summer.[10] Temperatures as low as −4 °C (25 °F) have been recorded in the Sevenmallay region of Munnar.[11]

Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies it as subtropical highland (Cwb).[12]

| Climate data for Munnar | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 22.4 (72.3) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.8 (73.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.4 (74.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.6 (63.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21 (70) |

21.4 (70.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.3 (63.1) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16.3 (61.3) |

16 (61) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.4 (59.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 18 (0.7) |

29 (1.1) |

47 (1.9) |

129 (5.1) |

189 (7.4) |

420 (16.5) |

583 (23.0) |

364 (14.3) |

210 (8.3) |

253 (10.0) |

164 (6.5) |

64 (2.5) |

2,470 (97.3) |

| Average rainy days | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 84 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 248 | 232 | 248 | 240 | 217 | 120 | 124 | 124 | 150 | 155 | 180 | 217 | 2,255 |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org, altitude: 1461m[12] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather2Travel for sunshine and rainy days[13] | |||||||||||||

Gallery

A beautiful sunrise scene at Munnar.

A beautiful sunrise scene at Munnar.- Tea plantations at Munnar

_(13694719014).jpg) Munnar Tea Museum

Munnar Tea Museum Beautiful view of Munnar tea plantation

Beautiful view of Munnar tea plantation- Mountain ranges covered by clouds at Munnar

Tea plantations at Munnar

Tea plantations at Munnar Munnar Heritage Tour, Lockhart Tea Factory

Munnar Heritage Tour, Lockhart Tea Factory Nilgiri Thar

Nilgiri Thar Chokarmudy View Point

Chokarmudy View Point- Kundala Dam and Lake

Attukad Water Falls

Attukad Water Falls View of Tea plantations

View of Tea plantations Lockhart Tea Museum

Lockhart Tea Museum

See also

- Bisonvalley

- Kolukkumalai

- Kunchithanny

- Marayur

- Mattupetty Dam

- Munnar Tea Museum

- Pallivasal

- Rajakkad

- Wayanad

References

- Munnar - Fallingrain

- "Munnar - the Hill Station of Kerala in Idukki | Kerala Tourism". Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- S, Muthiah (1993). A Planting Century 1893-1993. Madras: -West Pvt Ltd., 62-A Ormes Road, Kilpauk, Madras-600010. ISBN 81-85938-04-0.

- "Munnar May Soon Get Train Service, Nearly A Century After The 'Great Flood Of 99' Destroyed It". indiatimes.com. 24 June 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Munnar History Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "Munnar". Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Government of Kerala, Forest and Wildlife Department, Notification No. 36/2006 F&WLD". Kerala Gazette. 6 October 2006. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- Roy, Mathew (25 September 2006). "Proposal for Kurinjimala sanctuary awaits Cabinet nod". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- Jacob, Jeemon (12 July 2011). "Kerala government launches eviction drive in Munnar". Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- "Eravikulam National Park, Munnar, Kerala, India, the home of Nilgiri Tahr". Eravikulam National Park. Archived from Eravikulam the original Check

|url=value (help) on 12 May 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2013. - Frost hits plantations in Munnar

- "Climate: Munnar — Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- "Munnar Climate and Weather Averages, Kerala". Weather2Travel. Retrieved 28 August 2013.