Woolly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and northern Asia during the Pleistocene epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhinoceros was a member of the Pleistocene megafauna.

| Woolly rhinoceros | |

|---|---|

| |

| Woolly rhinoceros skeleton in Muséum de Toulouse | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genus: | †Coelodonta |

| Species: | †C. antiquitatis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Coelodonta antiquitatis (Bronn, 1831) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Rhinoceros lenenesis (Pallas) | |

The woolly rhinoceros was covered with thick and long hair, which allowed it to survive in the extremely cold, harsh mammoth steppe. It also had a massive hump reaching from its shoulder. It fed mainly on herbaceous plants that grew in the steppe.

Mummified carcasses preserved in permafrost and many bone remains of woolly rhinoceroses have been found. Images of woolly rhinoceroses are found among cave paintings in Europe and Asia.

Taxonomy

Woolly rhinoceros remains have been known long before the species was described, and were the basis for some mythical creatures. Native peoples of Siberia believed their horns were the claws of giant birds.[2] A rhinoceros skull was found in Klagenfurt, Austria, in 1335, and was believed to be that of a dragon.[3] In 1590, it was used as the basis for the head on a statue of a lindworm.[4] Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert maintained the belief that the horns were the claws of giant birds, and classified the animal under the name Gryphus antiquitatis, meaning "ancient griffin".[5]

One of the earliest scientific descriptions of an ancient rhinoceros species was made in 1769, when the naturalist Peter Simon Pallas wrote a report on his expeditions to Siberia where he found a skull and two horns in the permafrost.[6] In 1772, Pallas acquired a head and two legs of a rhinoceros from the locals in Irkutsk,[7] and named the species Rhinoceros lenenesis (after the Lena River).[8] In 1799, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach studied rhinoceros bones from the collection of the University of Göttingen, and proposed the scientific name Rhinoceros antiquitatis.[9] The geologist Heinrich Georg Bronn moved the species to Coelodonta in 1831 because of its differences in dental formation with members of the Rhinoceros genus.[10] This name comes from the Greek words κοιλία (koilía, "cavity") and ὀδούς (odoús "tooth"), from the depression in the rhino's molar structure,[11][12] giving the scientific name Coelodonta antiquitatis, "ancient hollow tooth".[13]

Evolution

The woolly rhinoceros was the most derived of the genus Coelodonta. The closest extinct relative to the woolly rhinoceros is Elasmotherium. These two lines were divided in the first half of the Miocene. A 1.77 million year old Stephanorhinus rhino mummy may also represent a sister group to Coelodonta.[14][15]

The woolly rhinoceros may have descended from the Eurasian C. tologoijensis or the Tibetan C. thibetana.[14] In 2011, a 3.6-million-year-old woolly rhinoceros fossil, the oldest known, was discovered on the cold Tibetan Plateau.[16]

A study of 40,000- to 70,000-year-old DNA samples showed its closest living relative is the Sumatran rhinoceros.[17]

Description

Structure and appearance

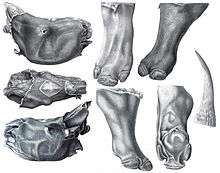

An adult woolly rhinoceros typically measured 3 to 3.8 metres (9.8 to 12.5 ft) from head to tail, with an estimated weight of around 1,800–2,700 kg (4,000–6,000 lb)[18] or 2,000 kg (4,400 lb).[19] It grew up to 2 m (6.6 ft) tall at the shoulder, about the same size as the white rhinoceros.[20] A one-month-old calf was about 120 centimetres (3.9 ft) in length and 72 centimetres (2.36 ft) tall at the shoulder.[21] The two horns were made of keratin, with one long horn reaching forward, and a smaller horn between the eyes.[22] Compared to other rhinoceroses, the woolly rhinoceros had a longer head and body, and shorter legs. Its shoulder was raised with a powerful hump, used to support the animal's massive front horn. The hump also contained a fat reserve to aid survival through the desolate winters of the mammoth steppe.[23]

Frozen specimens indicate that the rhino's long fur coat was reddish-brown, with a thick undercoat that lay under a layer of long, coarse guard hair thickest on the withers and neck. Shorter hair covered the limbs, keeping snow from attaching.[23] The body's length ended with a 45 to 50 centimetres (1.48 to 1.64 ft) tail with a brush of coarse hair at the end.[24] Females had two nipples on the udders.[19]

The woolly rhinoceros had several features reducing the body's surface area and minimized heat loss. Its ears were no longer than 24 centimetres (9.4 in), while those of rhinos in hot climates are about 30 centimetres (12 in).[25] Their tails were also relatively shorter. It also had thick skin, ranging from 5 to 15 millimetres (0.20 to 0.59 in), heaviest on the chest and shoulders.[14][25]

Skull and dentition

The skull had a length between 70 to 90 centimetres (28 to 35 in). It was longer than those of other rhinoceros, giving the head a deep, downward-facing slanting position, similar to its fossil relatives Stephanorhinus hemiotoechus and Elasmotherium as well as the white rhinoceros.[26] Strong muscles on its long occipital bone formed its neck hock and held the massive skull. Its massive lower jaw measured up to 60 centimetres (24 in) long and 10 centimetres (3.9 in) high.[25]

The nasal septum of the woolly rhinoceros was ossified, unlike modern rhinos. This was most common in adult males.[27] This adaptation probably evolved as a result of the heavy pressure on the horn and face when the rhinoceros grazed underneath the thick snow.[28] Unique to this rhino, the nasal bones were fused to the premaxillae, which is not the case in older Coelodonta types or today's rhinoceroses.[29]

The teeth of the woolly rhinoceros had thickened enamel and an open internal cavity.[25] Like other rhinos, adults did not have incisors.[30] It had 3 premolars and 3 molars in both jaws. The molars were high-crowned and had a thick coat of cementum.[11]

Paleobiology

The woolly rhinoceros had a similar life history to modern rhinos. Studies on milk teeth show that individuals developed similarly to both the white and black rhinoceros.[30] The two teats in the female suggest that she raised one calf, or more rarely two, every two to three years.[32][19] If similar to modern rhinos, calves lived with their mother for around 3 years before searching for their own individual territory, reaching sexual maturity within five years.[33][34] Woolly rhinoceroses could reach around 40 years of age, like their modern relatives.[35]

With their massive horns and size, adults had few predators, but young individuals could be attacked by animals such as hyenas and cave lions. A skull was found with trauma indicating an attack from a feline, but the animal survived to adulthood.[35]

Woolly rhinos may have used their horns for combat, probably including intraspecific combat as recorded in cave paintings, as well as for moving snow to uncover vegetation during winter.[14] They may have also been used to attract mates.[27] Bull woolly rhinos were probably territorial like their modern counterparts, defending themselves from competitors, particularly during the rutting season. Fossil skulls indicate damage from the front horns of other rhinos,[35] and lower jaws and back ribs show signs of being broken and re-formed, which may have also come from fighting.[36] The apparent frequency of intraspecific combat, compared to recent rhinos, was likely a result of rapid climatic change during the last glacial period, when the animal faced increased stress from competition with other large herbivores.[28]

Diet

Woolly rhinoceroses mostly fed on grasses and sedges that grew in the mammoth steppe. Its long, slanted head with a downward-facing posture, and tooth structure all helped it graze on vegetation.[25][26] It had a wide upper lip like that of the white rhinoceros, which allowed it to easily pluck vegetation directly from the ground.[19] Pollen analysis shows it also ate woody plants (including conifers, willows and alders),[25] along flowers,[37] forbs and mosses.[38] Isotope studies on horns show that the woolly rhinoceros had a seasonal diet; different areas of horn growth suggest that it mainly grazed in summer, while it browsed for shrubs and branches in the winter.[39]

A strain vector biomechanical investigation of the skull, mandible and teeth of a well-preserved last cold stage individual recovered from Whitemoor Haye, Staffordshire, revealed musculature and dental characteristics that support a grazing feeding preference. In particular, the enlargement of the temporalis and neck muscles is consistent with that required to resist the large tugging forces generated when taking large mouthfuls of fodder from the ground. The presence of a large diastema supports this theory.[40]

Comparisons with living perissodactyls confirm that the woolly rhinoceros was a hindgut fermentor with a single stomach, consuming cellulose-rich, protein-poor fodder. It had to consume a heavy amount of food to account for the low nutritive content of its diet. Woolly rhinos living in the Arctic during the Last Glacial Maximum consumed approximately equal volumes of forbs, such as Artemisia, and graminoids.[41]

Habitat and distribution

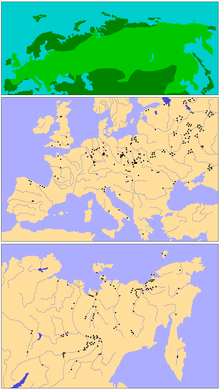

The woolly rhinoceros lived mainly in lowlands, plateaus and river valleys, with dry to arid climates,[42] and migrated to higher elevations in favourable climate phases. It avoided mountain ranges, due to heavy snow and steep terrain that the animal could not easily cross.[42] The rhino's main habitat was the mammoth steppe, a large, open landscape covered with wide ranges of grass and bushes. The woolly rhinoceros lived alongside other large herbivores, such as the woolly mammoth, giant deer, reindeer, saiga antelope and bison – an assortment of animals known as the Mammuthus-Coelodonta Faunal Complex.[43] With its wide distribution, the woolly rhinoceros lived in some areas alongside the other rhinoceroses Stephanorhinus[23] and Elasmotherium.[44]

By the end of the Riss glaciation about 130 thousand years ago, the woolly rhinoceros lived throughout northern Eurasia, spanning most of Europe, the Russian Plain, Siberia, and the Mongolian Plateau, ranging to extremes of 72° to 33°N. Fossils have been found as far north as the New Siberian Islands.[14][45] It had the widest range of any rhinoceros species.[46]

It seemingly did not cross the Bering land bridge during the last ice age (which connected Asia to North America), with its easterly-most occurrence at the Chukotka Peninsula,[14] probably due to the low grass density and lackof suitable habitat in the Yukon, competition with other large herbivores on the frigid land bridge, and vast glaciers creating physical barriers.[42] Even if some arrived in North America, this was probably uncommon.[45]

Relationship with humans

Hunting

Woolly rhinoceroses shared their habitat with humans, but direct evidence that they interacted is relatively rare. Only 11% of the known sites of prehistoric Siberian tribes have remains or images of the animal.[14] Many rhinoceros remains are found in caves (such as the Kůlna Cave in Central Europe), which were not the natural habitat of either rhinos or humans, and large predators such as hyenas may have carried rhinoceros parts there.[47] Sometimes, only individual teeth or bone fragments are uncovered, which usually came from only one animal.[48] Most rhinoceros remains in Western Europe are found in the same places where human remains or artifacts were found, but this may have occurred naturally.[49][50]

Signs that early humans hunted or scavenged the rhinoceros come from markings on the animal's bones. One specimen had injuries caused by human weaponry, with traces of a wound from a sharp object markings from a the shoulder and thigh, and a preserved spear was found near the carcass.[25] A few sites from the early phase of the Last Glacial Period in the late Middle Paleolithic, such as the Gudenus Cave (Austria)[51] and the open air site of Königsaue (Saxony-Anhalt, Germany),[52] have heavily beaten rhinoceros bones lined with slash marks. This action was done partly to extract the nutritious bone marrow.[53]

Both horns and bones of the rhinoceros were used as raw materials for tools and weapons, as were remains from other animals.[54] In what is now Zwoleń, Poland, a device was made from a battered woolly rhinoceros pelvis.[55] Half-meter spear throwers, made from a woolly rhinoceros horn about 27 thousand years ago, came from the banks of the Yana River.[56] A 13,300 year-old spear found on Bolshoy Lyakhovsky Island has a tip made of rhinoceros horn, the furthest north a human artifact has ever been found.[57]

The Pinhole Cave Man is a late Paleolithic figure of a man engraved on a rib bone of a woolly rhinoceros, found at Creswell Crags in England.[58]

Ancient art

Rhinoc%C3%A9rosEnFuite.jpg)

Many cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic depict woolly rhinoceroses. The animal's defining features are prominently drawn, complete with the raised back and hump, contrasting with its low-lying head. Two curved lines represent the ears. The animal's horns are drawn with their long curvature, and in some cases the coat is also indicated. Many paintings show a black band dividing the body.[59]

About 20 Paleolithic drawings of woolly rhinos were known before the discovery of the Chauvet Cave in France.[59] They are dated at over 31,000 years old, probably from the Aurignacian,[14] engraved on cave walls or drawn in red or black. One scene depicts two rhinos fighting each other with their horns.[60] Other illustrations are found in the Rouffignac and Lascaux caves. One drawing from Font-de-Gaume shows a noticeably higher head posture, and others were drawn in red pigments in the Kapova Cave in the Ural Mountains.[61] Some images show rhinoceroses struck with spears or arrows, signifying human hunting.[62]

The site of Dolní Věstonice in Moravia, Czech Republic, was found with more than seven hundred statuettes of animals, many of woolly rhinoceroses.[62]

Extinction

Many species of Pleistocene megafauna, like the woolly rhinoceros, became extinct around the same time period. Human hunting is often cited as one cause. Other theories for the cause of the extinctions are climate change associated with the receding Ice age and the hyperdisease hypothesis (q.v. Quaternary extinction event).[63] One of the more widely accepted theories states that, although the woolly rhinoceros was specialized for cold weather, it was capable of surviving in warmer climates. This suggests that climate change was not the only factor contributing to the rhinoceros's extinction. Other cold-adapted species, such as reindeer, muskox and wisent, survived this period of climatic change and many others like it, supporting the 'overkill' hypothesis for the woolly rhino.

Radiocarbon dating indicates that populations survived as recently as 8,000 BC in western Siberia.[64] However, the accuracy of this date is uncertain, as several radiocarbon plateaus exist around this time. The extinction does not coincide with the end of the last ice age, but does coincide with a minor yet severe climatic reversal that lasted for about 1,000–1,250 years, the Younger Dryas (GS1—Greenland Stadial 1), characterized by glacial readvances and severe cooling globally, a brief interlude in the continuing warming subsequent to the termination of the last major ice age (GS2), thought to have been due to a shutdown of the thermohaline circulation in the ocean due to huge influxes of cold fresh water from the preceding sustained glacial melting during the warmer Interstadial (GI1—Greenland Interstadial 1: ca. 16,000–11,450 14C years B.P.).

Fossil specimens

Frozen specimens

Many rhinoceros remains have been found preserved in the permafrost region. In 1771, a head, two legs and hide were found in the Vilyuy River in eastern Siberia and sent to the Kunstkamera in Saint Petersburg.[65] Later in 1877, a Siberian trader recovered a head and one leg from a tributary of the Yana River.[25]

In October 1907, miners in Starunia, Ukraine, found a mammoth carcass buried in an ozokerite pit. A month later, a rhinoceros was found 5 metres (16 ft) underneath.[66] Both were sent to the Dzieduszycki Museum, where a detailed description was published in the museum's monograph.[67] Photographs were published in paleontological journals and textbooks, and the first modern paintings of the species were based on the mounted specimen.[68] The rhino is now located in the Lviv National Museum along with the mammoth.[68] Later, in 1929, the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences sent an expedition to Starunia, finding the mummified remains of three rhinos.[69] One specimen, missing only its horns and fur, was taken to the Aquarium and Natural History Museum in Kraków. A plaster cast was made soon afterwards, which is now held in the Natural History Museum in London.[70]

Skull and rib fragments of a rhinoceros were found in 1972 in Churapcha, between the Lena and Amga rivers. A whole skeleton was found soon afterwards, with preserved skin, fur, and stomach contents.[25][71] In 1976, schoolchildren on a class trip found a 20,000 year old rhinoceros skeleton on the Aldan River's left bank, uncovering a skull with both horns, a spine, ribs and limb bones.[72]

In 2007, a partial rhinoceros carcass was found in the lower reaches of the Kolyma. Its upward-facing position indicates that the animal probably fell into mud and sank.[73][25] Next year in 2008, a nearly complete skeleton came from the Chukochya River.[74] That same year, locals near the Amga discovered mummified rhinoceros remains, and over the next two years, pelvic bones, tail vertebrae and ribs were excavated along with forelimbs and hind limbs with toes intact.[8]

In September 2014, a mummified young rhinoceros was discovered by two hunters, Alexander “Sasha” Banderov and Simeon Ivanov, at a tributary of the Semyulyakh River in the Abyysky District in Yakutia, Russia. Its head and horns, fur, and soft tissues were recovered. Some parts had been thawed and eaten, since they were not covered by permafrost. The body was handed over to the Yakutia Academy of Sciences, where it was named “Sasha” after one of its discoverers.[75] Dental analysis shows that the calf was about seven months old at the time of its death.[76] With its well-intact preservation, scientists proceeded to undergo DNA analysis.[77][78]

See also

- Elasmotherium, another Pleistocene Eurasian rhinoceros

References

- Pei Wen-Chung (1956). "Quaternary mammalian fossils from Hsintsai, South-Eastern part of Honan". Acta Palaeontologica Sinica. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018.

- Howorth, H.H. (1887). The Mammoth and the Flood: An Attempt to Confront the Theory of Uniformity with the Facts of Recent Geology. S. Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington. p. 7.

- Price, Samantha (2007-06-01). "Horns, Tusks, and Flippers: the Evolution of Hoofed Mammals" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals. Aquatic Mammals Journal. 33 (2): 254. doi:10.1578/am.33.2.2007.254. ISSN 0167-5427.

- "RRC: The Klagenfurt Lindwurm". RRC. | access-date=2019-12-08}}

- Schubert, von, G.H., 1823. Die Urwelt und die Fixsterne: eine Zugabe zu den Ansichten von der Nachtseite der Naturwissenschaft [The Primeval World and the Fixed Stars]. Arnoldischen Buchhandlung, Dresden.

- Pallas, P.S.; Blagdon, F.W. (1812). Travels Through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire: In the Years 1793 and 1794. Travels Through the Southern Provinces of the Russian Empire, in the Years 1793 and 1794. John Stockdale, Piccadilly.

- Owen, Richard. (1846). A History of British Fossil Mammals, and Birds. J. Van Voorst.

- Lazarev, P.A., Grigoriev, S.E., Plotnikov, V.V., 2010. Woolly rhinoceroses from Yakutia//evolution of life on the Earth. In: Proceedings of the IV International Symposium. TML-Press, Tomsk, pp. 555e558.

- Gehler, Alexander & Reich, Mike & Mol, Dick & Plicht, Hans. (2007). The type material of Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach) (Mammalia: Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae) / Типовой материал Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach) (Mammalia: Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae) / Tipovoj material Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach) (Mammalia: Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotidae).

- Bronn, H.G. (1838). Lethaea geognostica oder Abbildungen und Beschreibungen der für die Gebirgs-Formationen bezeichnendsten Versteinerungen [Lethaea Geognostica, or pictures and descriptions of the most characteristic fossils of the mountain formations] (in German). Stuttgart. p. 451.

- van der Made, Jan. "The rhinos from the Middle Pleistocene of Neumark-Nord (Saxony-Anhalt)" (PDF). Veröffentlichungen des Landesamtes für Archeologie [State Office of Archeology Saxony-Anhalt] (in German and English). 62: 432–527.

- von Koenigswald, W. (2002). Lebendige Eiszeit: Klima und Tierwelt im Wandel [Living Ice Age: Climate and wildlife in transition] (in German). Theiss. ISBN 978-3-8062-1734-6.

- RFE/RL (2012-12-06). "Siberia Surrenders Woolly Rhino Mysteries". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- Stuart, Anthony J.; Lister, Adrian M. (2012). "Extinction chronology of the woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis in the context of late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions in northern Eurasia" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 51: 1–17. Bibcode:2012QSRv...51....1S. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.06.007. ISSN 0277-3791.

- Cappellini, Enrico & Welker, Frido & Pandolfi, Luca & Ramos Madrigal, Jazmín & Fotakis, Anna & Lyon, David & Mayar, Victor & Bukhsianidze, Maia & Jersie-Christensen, Rosa & Mackie, Meaghan & Ginolhac, Aurélien & Ferring, Reid & Tappen, Martha & Palkopoulou, Eleftheria & Samodova, Diana & Ruther, Patrick & Dickinson, Marc & Stafford, Tom & Chan, Yvonne & Willerslev, Eske. (2018). Early Pleistocene enamel proteome sequences from Dmanisi resolve Stephanorhinus phylogeny. 10.1101/407692.

- "Ice Age giants may have evolved in Tibet". CNN. 1 September 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- Orlando, L.; Leonard, J. A.; Thenot, A. L.; Laudet, V.; Guerin, C.; Hänni, C. (2003). "Ancient DNA analysis reveals woolly rhino evolutionary relationships". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 28 (3): 485–499. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00023-X. PMID 12927133.

- "Extinct Woolly Rhino". International Rhino Foundation. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- Boeskorov, G. G. (2012). "Some specific morphological and ecological features of the fossil woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach 1799)". Biology Bulletin. 39 (8): 692–707. doi:10.1134/S106235901208002X.

- Krause, Hans (2011). "HKHPE 07 02". hanskrause.de. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- Shpansky, A.V. (2014). "Juvenile remains of the "woolly rhinoceros" Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach 1799) (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from the Tomsk Priob'e area (southeast Western Siberia)" (PDF). Quaternary International. Elsevier BV. 333: 86–99. Bibcode:2014QuInt.333...86S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2014.01.047. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Fortelius, Mikael (1983). "The morphology and paleobiological significance of the horns of Coelodonta antiquitatis (Mammalia: Rhinocerotidae)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 3 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1080/02724634.1983.10011964. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Kahlke, Ralf-Dietrich; Lacombat, Frédéric (2008-11-01). "The earliest immigration of woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta tologoijensis, Rhinocerotidae, Mammalia) into Europe and its adaptive evolution in Palaearctic cold stage mammal faunas" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 27 (21–22): 1951–1961. Bibcode:2008QSRv...27.1951K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2008.07.013. ISSN 0277-3791. | last1=Kahlke | first1=Ralf-Dietrich | last2=Lacombat | first2=Frédéric }}

- Kalandadze N.N., Shapovalov A.V. & Tesakova E.M.— On nomenclatural problems concerning woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach, 1799) // Researches on paleontology and biostratigraphy of ancient continental deposits (Memories of Professor Vitalii G. Ochev). Eds. M.A. Shishkin & V.P. Tverdokhlebov.— Saratov: «Nauchnaya Kniga» Publishers, 2009. P. 98–111.

- Boeskorov, Gennady G.; Lazarev, Peter A.; Sher, Andrei V.; Davydov, Sergei P.; Bakulina, Nadezhda T.; Shchelchkova, Marina V.; Binladen, Jonas; Willerslev, Eske; Buigues, Bernard; Tikhonov, Alexey N. (2011-08-01). "Woolly rhino discovery in the lower Kolyma River" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17–18): 2262–2272. Bibcode:2011QSRv...30.2262B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.02.010. ISSN 0277-3791.

- van der Made, Jan; Grube, René (2010). Meller, Harald (ed.). The rhinoceroses from Neumark-Nord and their nutrition (PDF) (in German and English). Halle/Saale. pp. 382–394.

- Shidlovskiy, Fedor K.; Kirillova, Irina V.; Wood, John (2012). "Horns of the woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach, 1799) in the Ice Age Museum collection (Moscow, Russia)" (PDF). Quaternary International. Elsevier BV. 255: 125–129. Bibcode:2012QuInt.255..125S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.06.051. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Garutt, N.V. (1998). Woolly Rhinoceros: Morphology, Systematics and Geological Significance (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation abstract). Russian Mining Institute.

- Mazza, Paul; Azzaroli, A. (1993). "Ethological inferences on Pleistocene rhinoceroses of Europe". Rendiconti Lincei. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 4 (2): 127–137. doi:10.1007/bf03001424. ISSN 1120-6349.

- Garutt, N.V. "Dental ontogeny of the woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach, 1799)" (PDF). Cranium. 11 (1).

- "Woolly rhinoceros". World Museum of Man. Archived from the original on 2015-09-20.

- "Почему вымер шерстистый носоро" [Why the woolly rhino died out]. All-Russian Festival of Science (in Russian). 2012-04-22. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Bradford, Alina (2018-03-20). "Facts About Rhinos". livescience.com. Retrieved 2019-12-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ballenger, Liz; Myers, Phil (2002-09-04). "Rhinocerotidae (rhinoceroses)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2019-12-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garutt, N.V. (1997). "Traumatic skull damages in the woolly rhinoceros, Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach, 1799" (PDF). Cranium. 14 (1): 37–46.

- Diedrich, Cajus (2008). "A skeleton of an injured Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach, 1807) from the Upper Pleistocene of north-western Germany" (PDF). Cranium. 25 (1): 1–16.

- "Woolly Mammoths and Rhinos Ate Flowers". livescience.com. 2014-02-05. Retrieved 2019-11-07.

- Dale Guthrie, R. (1990). Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe. ISBN 9780226311234.

- Tiunov, Alexei & Kirillova, Irina. (2010). Stable isotope (C-13/C-12 and N-15/N-14) composition of the woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis horn suggests seasonal changes in the diet. Rapid communications in mass spectrometry : RCM. 24. 3146-50. 10.1002/rcm.4755.

- Schreve, Danielle; Howard, Andy; Currant, Andrew; Brooks, Stephen; Buteux, Simon; Coope, Russell; Crocker, Barnaby; Field, Michael; Greenwood, Malcolm; Greig, James; Toms, Phillip (2012-12-18). "A Middle Devensian woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis) from Whitemoor Haye Quarry, Staffordshire (UK): palaeoenvironmental context and significance" (PDF). Journal of Quaternary Science. Wiley. 28 (2): 118–130. doi:10.1002/jqs.2594. ISSN 0267-8179.

- Willerslev E, Davison J, Moora M, Zobel M, Coissac E, Edwards ME, Lorenzen ED, Vestergård M, Gussarova G, Haile J, Craine J, Gielly L, Boessenkool S, Epp LS, Pearman PB, Cheddadi R, Murray D, Bråthen KA, Yoccoz N, Binney H, Cruaud C, Wincker P, Goslar T, Alsos IG, Bellemain E, Brysting AK, Elven R, Sønstebø JH, Murton J, Sher A, Rasmussen M, Rønn R, Mourier T, Cooper A, Austin J, Möller P, Froese D, Zazula G, Pompanon F, Rioux D, Niderkorn V, Tikhonov A, Savvinov G, Roberts RG, MacPhee RD, Gilbert MT, Kjær KH, Orlando L, Brochmann C, Taberlet P (2014). "Fifty thousand years of Arctic vegetation and megafaunal diet" (PDF). Nature. 506 (7486): 47–51. Bibcode:2014Natur.506...47W. doi:10.1038/nature12921. PMID 24499916.

- Boeskorov, G. "Woolly rhino (Coelodonta antiquitatis) distribution in Northeast Asia" (PDF). Deinsea. 8 (1).

- Kahlke, Ralf-Dietrich (2014-07-15). "The origin of Eurasian Mammoth Faunas (Mammuthus–Coelodonta Faunal Complex)" (PDF). Quaternary Science Reviews. 96: 32–49. Bibcode:2014QSRv...96...32K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.01.012. ISSN 0277-3791.

- Pushkina, Diana (2007). "The Pleistocene easternmost distribution in Eurasia of the species associated with the Eemian Palaeoloxodon antiquus assemblage". Mammal Review. Wiley. 37 (3): 224–245. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2007.00109.x. ISSN 0305-1838.

- Garutt, N. V., & Boeskorov, G. G. (2001). Woolly rhinoceroses: On the history of the genus. Mamont i ego okruzhenie, 200, 157-167.

- Prothero, D.R., Guérin, C. & Manning, E. 1989. The History of Rhinocerotoidea. In: The Evolution of Perissodactyls (eds. Prothero, D. R. & Schoch, R.M.). Oxford University Press, New York, 321-340.

- Diedrich, Cajus (2008). "Eingeschleppte und benagte Knochenreste von Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach 1807) aus dem oberpleistozänen Fleckenhyänenhorst Perick-Höhlen im Nordsauerland (NW Deutschland) und Beitrag zur Taphonomie von Wollnashornknochen in Westfalen" (PDF). Mitteilungen der Höhlen und Karstforscher (in German): 100–117.

- Bratlund, B. (2005). Comments on a cut-marked woolly rhino mandible from Zwolen. In: R. Schild (ed.), The killing fields of Zwolén. A Middle Paleolithic kill-butchery-site in Central Poland. Warsaw, Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences: 217-221.

- Baumann, Willfried; Mania, Dietrich (1983). "Ein mittelpaläolithisches Rentierlager bei Salzgitter-Lebenstedt" [A Middle Paleolithic reindeer site near Salzgitter-Lebenstedt.]. Die paläolithischen Neufunde von Markkleeberg bei Leipzig (Mit Beiträgen von L. Eißmann und V. Toepfer). Veröffentlichungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Dresden. (in German). Berlin. Band 16.

- Guérin, Claude (2010). "Coelodonta antiquitatis praecursor (Rhinocerotidae) du Pléistocène moyen final de l'aven de Romain-la-Roche (Doubs, France)" [The Late Middle Pleistocene Coelodonta antiquitatis praecursor (Rhinocerotidae) from the sinkhole of Romain-la-Roche (Doubs, France)] (in French). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Döppes, Doris (1997). "Die jungpleistozäne Säugetierfauna der Gudenushöhle (Niederösterreich)" [The Late Pleistocene mammal fauna of the Gudenus Cave (Lower Austria)]. Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen des Niederösterreichischen Landesmuseums [Scientific communications of the Lower Austria Museum] (in German). 10: 17–32.

- Mania, Dietrich; Toepfer, V. (1973). "Königsaue. Gliederung, Ökologie und mittelpaläolithische Funde der letzten Eiszeit. Veröffentlichungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle/Saale" (in German). 26. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ashton, N.; Lewis, S.; Stringer, C. (2010). The Ancient Human Occupation of Britain. ISSN. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-444-53598-6.

- Gaudzinski, S. 1999a. The faunal record of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic of Europe: remarks on human interference. In The Middle Palaeolithic Occupation of Europe. (ed. W. Roebroeks and C. Gamble) Leiden: University of Leiden, pp. 215 - 233.

- Schild, R. (2005). The Killing Fields of Zwolén: A Middle Paleolithic Kill-butchery-site in Central Poland. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, Polish Academy of Sciences. pp. 2017–216. ISBN 978-83-89499-23-3.

- Nikolskiy, Pavel; Pitulko, Vladimir (2013). "Evidence from the Yana Palaeolithic site, Arctic Siberia, yields clues to the riddle of mammoth hunting". Journal of Archaeological Science. Elsevier BV. 40 (12): 4189–4197. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.05.020. ISSN 0305-4403.

- "13,300 year old spear made of woolly rhinoceros horn found on Arctic island". Siberian Times.

- "engraved bone/antler". British Museum.

- Bahn, P.G.; Vertut, J. (1997). Journey Through the Ice Age. University of California Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-520-22900-6.

- Foundation, Bradshaw. "Fighting Rhino & Four Horses - The Cave Art Paintings of the Chauvet Cave". Bradshaw Foundation. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- "Kapova Cave". Don's Maps. Retrieved 24 Aug 2019.

- Guthrie, R.D. (2005). The Nature of Paleolithic Art. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-31126-5.

- Grayson, D. K.; Meltzer, D. J. (2003). "A requiem for North American overkill" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 30 (5): 585–593. doi:10.1016/S0305-4403(02)00205-4.

- Orlova, L. A.; Vasil’ev, S. K.; Kuz’min, Ya. V.; Kosintsev, P. A. (2008). "New data on the time and place of extinction of the woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis Blumenbach, 1799" (PDF). Doklady Biological Sciences. Pleiades Publishing Ltd. 423 (1): 403–405. doi:10.1134/s0012496608060100. ISSN 0012-4966. PMID 19213420.

- "Three Centuries of Hunting for Ice Age Mummies and the Prospect of De-Extinction". Capeia. 2018-05-18. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- Kotarba, Maciej J.; Dzieniewicz, Marek; Móscicki, Wlodzimierz J.; Sechman, Henryk (2008-07-01). "Unique Quaternary environment for discoveries of woolly rhinoceroses in Starunia, fore-Carpathian region, Ukraine: Geochemical and geoelectric studies". Geology. 36 (7): 567–570. Bibcode:2008Geo....36..567K. doi:10.1130/G24654A.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- Bayger, J.A., Hoyer, H., Kiernik, E., Kulczyński, W., Łomnicki, M., Łomnicki J., Mierzejewski, W., Niezabitowski, E., Raciborski, W., Szafer, W. & Schille, F., 1914. Wykopaliska staruńskie. Słoń mamut (Elephas primigenius Blum.) i nosorożec włochaty (Rhinoceros antiquitatis Blum. s. tichorhinus Fisch.) wraz z współczesną florą i fauną. Muzeum im. Dzieduszyckich we Lwowie, 15, 386 pp + atlas (67 tab.). (In Polish).

- Chornobay, Yuriy M.; Drygant, Daniel M. (2009). "The Starunia collections in the Natural History Museum of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Lviv" (PDF). Geotourism/Geoturystyka. 3 (18): 45–50. doi:10.7494/geotour.2009.18.3.45. ISSN 1731-0830.

- Kucha, Henryk (2009). "The Starunia collections in the Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals, Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków" (PDF). Geotourism/Geoturystyka. AGHU University of Science and Technology Press. 18 (1): 71. doi:10.7494/geotour.2009.18.71. ISSN 1731-0830.

- Nowak, J., Panow, E., Tokarski, J., Szafer, W. & Stach, J. 1930. The second woolly rhinoceros (Coelodonta antiquitatis Blum.) from Starunia, Poland (Geology, Mineralogy, Flora and Fauna). Classe des Sciences Mathématiques et Naturelles, Série B: Sciences Naturelles, Supplément 1-47.

- Lazarev, P.A., Boeskorov, G.G., Tomskaya, A.I., Garutt, N.V., Vasil’ev, E.M., and Kasparov, A.K., Mlekopitayushchie antropogena Yakutii (Mammals of the Anthropogene in Yakutia), Yakutsk: Yakut. Nauch. Tsentr Akad. Nauk SSSR, 1998.

- "Woolly Rhino Fossils Found". The New York Times. 1976-10-10.

- Boeskorov, G. G.; Lazarev, P. A.; Bakulina, N. T.; Shchelchkova, M. V.; Davydov, S. P.; Solomonov, N. G. (2009). "Preliminary study of a mummified woolly rhinoceros from the lower reaches of the Kolyma River" (PDF). Doklady Biological Sciences. 424 (1): 53–56. doi:10.1134/s0012496609010165. ISSN 0012-4966. PMID 19341085.

- Kirillova, Irina V.; Shidlovskiy, Fedor K. (2010-11-01). "Estimation of individual age and season of death in woolly rhinoceros, Coelodonta antiquitatis (Blumenbach, 1799), from Sakha-Yakutia, Russia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 29 (23–24): 3106–3114. Bibcode:2010QSRv...29.3106K. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.06.036. ISSN 0277-3791.

- Liesowska, Anna. "Meet Sasha - the world's only baby woolly rhino". The Siberian Times.

- Liesowska, Anna. "Lifelike again after 34,000 years, the world's only baby woolly rhino". Siberian Times.

- Liesowska, Anna (2019-12-23). "Sasha, the world's only baby woolly rhino, is 34,000 years old, say scientists". Siberian Times.

- Chernova, O. F.; Protopopov, A. V.; Perfilova, T. V.; Kirillova, I. V.; Boeskorov, G. G. (2016). "Hair microstructure of the first time found calf of woolly rhinoceros Coelodonta antiquitatis" (PDF). Doklady Biological Sciences. 471 (1): 291–295. doi:10.1134/s0012496616060090. ISSN 0012-4966. PMID 28058607.

- Parker, Steve. Dinosaurus: The Complete Guide to Dinosaurs. Firefly Books Inc, 2003. Pg. 422.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coelodonta antiquitatis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Coelodonta antiquitatis |