Zygmunt Krasiński

Zygmunt Krasiński (Polish pronunciation: [ˈzɨɡmunt kraˈɕiɲskʲi]; 19 February 1812 – 23 February 1859) was a Polish poet traditionally ranked with Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki as one of Poland's Three Bards – the trio of Romantic poets who influenced national consciousness in the period of Poland's political bondage. He was the most famous member of the aristocratic Krasiński family.

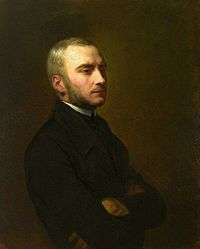

Count Napoleon Stanisław Adam Feliks Zygmunt Krasiński | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Ary Scheffer | |

| Born | 19 February 1812 Paris, France |

| Died | 23 February 1859 (aged 47) Paris |

| Resting place | Opinogóra Górna |

| Occupation | Poet, writer |

| Language | Polish |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Citizenship | Russian |

| Period | 1820s – 1859 |

| Genre | dramas, lyrical poems, letters |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Notable works | The Undivine Comedy Irydion Psalms of the Future |

| Spouse | Eliza Branicka |

| Children | with Eliza Branicka: Władysław Krasiński Zygmunt Jerzy Krasiński Maria Beatrix Krasińska Eliza Krasińska |

| Relatives | Wincenty Krasiński (father) Maria Urszula Radziwiłł (mother) the Krasiński family |

| Signature |  |

Early on, his main works were considered to be the poems Przedświt (Predawn) and Psalms of the Future, but in time he became more known for his prose works, dramas, and letters. He authored two major dramas, The Undivine Comedy (his most famous and enduring work) and Irydion.[1][2][3][4]

Life

Childhood

Napoleon Stanisław Adam Feliks Zygmunt Krasiński was born in Paris on 19 February 1812 to Count Wincenty Krasiński, a Polish aristocrat and military commander, and Countess Maria Urszula Radziwiłł.[1] He spent his first years in Chantilly, where Napoleon Bonaparte's Imperial Guard Regiment was stationed, and the Emperor himself attended his baptism.[1] In 1814 the two-year-old moved with his parents to Warsaw, then part of the Duchy of Warsaw, ruled by Frederick Augustus I of Saxony as a client state of the First French Empire.[1] Krasiński's cultivated and doting father employed prominent teachers and tutors, including Baroness Helena de la Haye, Józef Korzeniowski, and Piotr Chlebowski, to educate Zygmunt.[1]

Following the stabilization brought by the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which saw the end of the Duchy of Warsaw and the creation of Congress Poland, the Krasiński family spent most summer vacations and holidays on their estates in Podole and Opinogóra. On 12 April 1822 Zygmunt's mother suddenly died of tuberculosis, and the ten-year-old boy became a precocious close companion to the family head, who instilled in Zygmunt a reverence for chivalry and honor.[1] Zygmunt's fascination with his father's personality, and their mutual hopes for a free Poland, led to an excessive, onerous mutual idealization.[1] [1]

In September 1826 Zygmunt entered the Warsaw Lyceum (a secondary school which Chopin had attended in 1823–26), graduating in the autumn of 1827.[1] He began studies in law and administration at the Imperial University of Warsaw. In March 1829, however, an incident occurred that would result in Krasiński's expulsion from the university.[5] The incident resulted from Krasiński's attendance at classes instead of at a patriotic demonstration during the funeral of Marshal Piotr Beliński. Krasiński had boycotted the funeral at the urging of his father, who the previous year had clashed politically with Beliński. Beliński was widely seen as a national hero, and on 14 March 1829 Krasiński was publicly criticized by a student, Leon Łubieński, leading to an altercation. This was serious enough to involve the university administration and resulted in Krasiński's expulsion.[1][5][6]

From late May to mid-June Zygmunt took his first journey abroad, to Vienna, with his father, who had previously traveled to Austria.[1] In October 1829 Zygmunt left Poland to study abroad.[1] Via Prague, Plzen, Regensburg, Zurich, and Bern, 17-year-old Krasiński arrived on 3 November 1829 in Geneva.[1]

Literary travels

Much of Krasiński's time in Geneva was divided among social life, attendance at university lectures, and being tutored in subjects such as music.[1] He soon mastered the French language, in which he became as fluent as in his native Polish.[7] His Geneva stay was important to the shaping of the young writer's personality.[1] Soon after arrival in Geneva, at the beginning of November 1829, he met Henry Reeve, a physician's son who was in Switzerland to study philosophy and literature. The talented young Englishman, who composed overwrought romantic poetry, greatly inspired young Krasiński. They became fast friends and exchanged letters discussing their love of classical and romantic literature.[1]

At the beginning of 1830, Krasiński developed romantic feelings for Henrietta Willan, the daughter of a wealthy English merchant and tradesman. This relationship provided new experiences and inspired future works by Krasiński.[1]

On 11 August 1830 Krasiński met Adam Mickiewicz, a principal figure in Polish Romanticism, widely regarded as Poland's greatest poet.[1] Krasiński's wide-ranging conversations with Mickiewicz, who dazzled Krasiński with the breadth of his knowledge, were vital in shaping Krasiński's literary techniques.[1] From 14 August to 1 September 1830 they traveled together to the High Alps; Krasiński described this in his diary and wrote of the trip in a 5 September 1830 letter to his father.[1]

Around early November 1830 Krasiński left Geneva and traveled to Italy, visiting Milan, Florence, and Rome.[1] In Rome, receiving news about the outbreak of the November Uprising in Poland, he broke off his trip and returned to Geneva. He had been finishing a historical novel, Agaj-Han, considered his most significant work of that period.[1] On the advice of his father, who opposed rebellion against the Russian Empire (he had become a Russian general), he did not go to Poland to participate in the Uprising – to his later everlasting regret. In May 1832 he set out for Poland, on the way again visiting Italy (Milan, Verona, Vicenza, Padua, Venice), then Innsbruck and Vienna, finally by mid-August 1832 arriving in Warsaw.[1]

Having reunited with his father shortly afterward, they traveled together to Saint Petersburg, where he received an audience with the Russian Tsar. The elder Krasiński tried to arrange a diplomatic career for his son with the Russian Empire, but Zygmunt was not interested and was content to travel abroad again. In March 1833 he left Saint Petersburg and, visiting Warsaw and Kraków, traveled once more to Italy, where he would stay until 19 April 1834.[1] This period saw the creation of what is likely his most famous work, the drama The Undivine Comedy (Nie-Boska komedia), written probably between summer and fall 1834.[1] Like many of his works, it was published anonymously, to protect his family from possible repercussions in the Russian Empire, as his works were often outspoken and contained thinly veiled references to current politics.[1][7]

In Rome Krasiński fell in love with Joanna Bobrowa. Though the relationship lasted for a few years, it did not result in marriage (in any case, Bobrowa was already married).[1] With her and her husband Teodor, in the spring of 1834, Krasiński took another trip to Italy. That summer he met his father in Kissingen, then traveled to Wiesbaden and Ems. Autumn saw him visit Frankfurt and Milan, and by November he returned to Rome. In spring the following year he visited Naples, Pompeii, Sorrento, then Florence. In this period he finished another major work, the drama Irydion, which he had begun earlier, around 1832 or 1833.[1]

Departing Florence in June 1835, he met Bobrowa in Kissingen, then traveled with her to Ischl and Trieste, and then on alone to Vienna, which he reached in January 1836. Then he went to Milan and Florence, and again to Rome. In Rome, in May that year, he would meet and befriend another major Polish literary figure, Juliusz Słowacki. In summer 1836 he returned to Kissingen and visited Grafenberg, where he once more met his father. In November he returned to Vienna, where he stayed until June 1837. That summer he visited Kissingen and Frankfurt am Main, then returned by September to Vienna.[1]

Worsening health prevented him from resuming his travels until May 1838, when he traveled to Olomouc and Salzbrunn, then returned to Poland, in June visiting family estates in Opinogóra Górna. Shortly after, he traveled to Warsaw and then Gdańsk. September marked the end of his romance (which his father had opposed) with Joanna Bobrowa.[1] On 1 September 1838, together with his father, he again departed for Italy (Venice, Florence, Rome, and Naples). In Rome he once again met Juliusz Słowacki.[1]

Later life

Krasiński's muse for many years was Countess Delfina Potocka (likewise a friend of composer Frédéric Chopin), with whom he conducted a romance from 1838 to 1848.[1][7] In the first half of 1839 he traveled to Sicily, meeting Potocka in Switzerland, and his father in Dresden. He spent much of that time traveling with Potocka and writing poems and other works dedicated to her.[1] In July 1840 his father informed the 28-year-old of plans that he had made for Zygmunt to marry Countess Eliza Branicka (1820–1876). The marriage eventuated on 26 July 1843 in Dresden.[1] The couple would have four children: sons Władysław and Zygmunt, and daughters Maria Beatrix and Elżbieta.[1]

As usual, much of Krasiński's time was divided between traveling and writing.[1] The year 1843 also saw the publication of his poem Przedświt (Predawn).[1]

In 1845 he published another major work, Psalmy przyszłości (Psalms of the Future).[1] Tirelessly continuing his travels through Central Europe, in January 1848, in Rome he met another Polish literary figure, the struggling poet Cyprian Norwid (sometimes considered a fourth Polish bard), whom he would aid financially. He also met Mickiewicz again, and endorsed the political faction of Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski. Krasiński was critical of the revolutionary Spring of Nations.[1]

In 1850 his health worsened, but that did not stop his constant travels, including to France. Through letters and audiences with European figures, including Napoleon III, whom he met in 1857 and 1858, he sought to gain support for the Polish cause. In 1856, in Paris, he took part in the funeral of Adam Mickiewicz. On 24 November 1857, in a major blow to Krasiński, his father died.[1]

Krasiński himself shortly died, in Paris, on 23 February 1859.[1] His body, like his father's, was transported to Poland and laid to rest in the family crypt at Opinogóra.[1] Today the former family estate of the Krasiński family is the site of the Museum of Romantism.[8]

Works

Krasiński is best known for his Messianist philosophical ideas and tragic dramas.[9] Key themes in his writings include the necessity of sacrifice and suffering to moral progress, and providentialism.[1] His relation to his father, who strongly influenced – indeed, controlled – many aspects of his life, is also seen as a major influence in his writings.[10][11]

Krasiński's early works, particularly his historical novels such as Agaj-Han recounting the story of Marina Mniszech, were influenced by Walter Scott and Lord Byron[11] and extolled medieval chivalry.[7]

Krasiński's best-known work is the drama Nie-boska komedia (The Undivine Comedy).[1][7][12] In the 19th century, a still greater Polish Romantic poet, Adam Mickiewicz, discussed The Undivine Comedy in his lectures at the Collège de France, calling it "the highest achievement of the Slavic theater".[13] A century later, another Polish poet and lecturer on the history of Polish literature, Nobel literature laureate Czesław Miłosz, called The Undivine Comedy "truly pioneering" and "undoubtedly a masterpiece not only of Polish but... of world literature", and noted how surprising it is that such a brilliant drama could have been created by an author barely out of his teens.[7][14]

Krasiński's Undivine Comedy effectively discussed the concept of class struggle before Karl Marx had coined the phrase.[7][14] The Divine Comedy appears to have been inspired by the author's reflections on the disastrous Polish November 1830 Uprising and on the French July 1830 Revolution.[1][7] It contemplates social revolution, predicts the destruction of the nobility, and comments on societal changes wrought by western Europe's burgeoning capitalism. The play is critical both of the cowardly aristocracy and of the revolutionaries, whom it portrays as a destructive force. Also addressed are such themes as a poet's identity, the nature of poetry, and Romantic myths of perfect love, fame, and happiness.[1]

In another prose drama, Irydion, Krasiński again takes up the theme of societal decay.[14][11] He condemns the excesses of revolutionary movements, arguing that motives such as retribution have no place within the Christian ethic; many contemporaries, however, saw the play as an endorsement of militant struggle for Poland's independence, whereas Krasiński's intent was to advocate for organic work as a means to society's advancement.[1] His later works more clearly showed his opposition to romantic, militant ventures and his support for peaceful, organic educational work; this was particularly so in his Psalms of the Future, which was expressly critical of the concept of revolution.[1] Krasiński began writing Irydion before The Undivine Comedy, but published it after the latter. Miłosz comments that, while Irydion is a work of considerable talent, especially in its insightful analysis of the decadence of Rome, it is not on a par with The Undivine Comedy.[3]

Krasiński's more mature work includes a body of poetry, but his lyrical poetry is not particularly notable; indeed, he himself remarked that he was not a very gifted poet.[3][8] More memorable are his "treatises in the philosophy of history", especially Predawn and Psalms of the Future, influenced by philosophers including Hegel, Schelling, Cieszkowski, and Trentowski.[3] Krasiński's rejection of Romantic ideals and democratic slogans which he felt inspired futile bloody rebellions, brought a polemical reply from fellow poet Juliusz Słowacki in the form of the poem, Odpowiedź na Psalmy przyszłości (A reply to the Psalms of the Future)..[1][3][8]

Krasiński was a prolific writer of letters, some of which survived and were published posthumously.[1][11][7]

Polish literary scholar Zbigniew Sudolski notes, in the Polish Biographical Dictionary, that Krasiński has traditionally been ranked with Mickiewicz and Słowacki as one of Poland's Three National Bards.[1] Of the three, however, Krasiński is considered the least influential.[2] Czesław Miłosz writes that Krasiński, popular in the mid-19th century, remains an important figure in the history of Polish literature but is not on a par with Mickiewicz and Słowacki.[3]

Gallery

- Count Krasiński's family coat-of-arms

- Church crypt in Opinogóra Górna, Poland: graves of Krasiński's family and parents

See also

- History of philosophy in Poland

- List of Poles

- Romanticism in Poland

References

- Sudolski, Zbigniew (2016). "Zygmunt Krasiński". Internetowy Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2019-08-12.

- Markus Winkler (31 August 2018). Barbarian: Explorations of a Western Concept in Theory, Literature, and the Arts: Vol. I: From the Enlightenment to the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Springer. p. 202. ISBN 978-3-476-04485-3.

- Czeslaw Milosz (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Segel, Harold B. (8 April 2014). Polish Romantic Drama: Three Plays in English Translation. Routledge. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-134-40042-3.

- Czesław Miłosz, "Zygmunt Krasiński (1812–1859)", The History of Polish Literature, 2nd ed., Berkeley, University of California Press, 1983, ISBN 0-520-04477-0, p. 243.

- Markus Winkler (31 August 2018). Barbarian: Explorations of a Western Concept in Theory, Literature, and the Arts: Vol. I: From the Enlightenment to the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Springer. p. 203. ISBN 978-3-476-04485-3.

- Czeslaw Milosz (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Floryńska-Lalewicz, Halina (2004). "Zygmunt Krasiński". Culture.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2020-05-25.

- "Zygmunt Krasiński". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- Czeslaw Milosz (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Jerzy Jan Lerski; George J. Lerski; Halina T. Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- Wacław Walecki (1997). A short history of Polish literature. Polish Academy of Sciences, Cracow Branch. p. 29.

- Czeslaw Milosz (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

- Czeslaw Milosz (24 October 1983). The History of Polish Literature, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

External links

- (in Polish) Biography at poezja.org

- Works by Zygmunt Krasiński at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Zygmunt Krasiński at Internet Archive

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Zygmunt Krasiński |

| Polish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |