Edvard Grieg

Edvard Hagerup Grieg (/ɡriːɡ/ GREEG, Norwegian: [ˈɛ̀dvɑɖ ˈhɑ̀ːɡərʉp ˈɡrɪɡː]; 15 June 1843 – 4 September 1907) was a Norwegian composer and pianist. He is widely considered one of the leading Romantic era composers, and his music is part of the standard classical repertoire worldwide. His use and development of Norwegian folk music in his own compositions brought the music of Norway to international consciousness, as well as helping to develop a national identity, much as Jean Sibelius did in Finland and Bedřich Smetana did in Bohemia.[1]

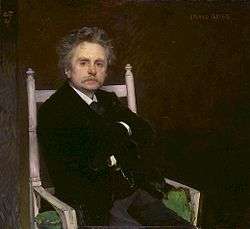

Edvard Grieg | |

|---|---|

_by_Elliot_and_Fry_-_02.jpg) Grieg in 1888, with signature, portrait published in The Leisure Hour (1889) | |

| Born | 15 June 1843 |

| Died | 4 September 1907 (aged 64) Bergen |

| Occupation |

|

Works | List of compositions |

| Spouse(s) | Nina Grieg (née Hagerup) |

Grieg is the most celebrated person from the city of Bergen, with numerous statues depicting his image, and many cultural entities named after him: the city's largest concert building (Grieg Hall), its most advanced music school (Grieg Academy) and its professional choir (Edvard Grieg Kor). The Edvard Grieg Museum at Grieg's former home, Troldhaugen, is dedicated to his legacy.[2][3][4][5]

Background

Edvard Hagerup Grieg was born in Bergen, Norway (then part of Sweden–Norway). His parents were Alexander Grieg (1806–1875), a merchant and vice-consul in Bergen; and Gesine Judithe Hagerup (1814–1875), a music teacher and daughter of solicitor and politician Edvard Hagerup.[6][7] The family name, originally spelled Greig, is associated with the Scottish Clann Ghriogair (Clan Gregor).[8] After the Battle of Culloden in 1746, Grieg's great-grandfather, Alexander Greig,[9] travelled widely, settling in Norway about 1770, and establishing business interests in Bergen. Grieg's first cousin, twice removed, was Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, whose mother was a Grieg.[10]

Edvard Grieg was raised in a musical family. His mother was his first piano teacher and taught him to play at the age of six. Grieg studied in several schools, including Tanks Upper Secondary School.[11]

In the summer of 1858, Grieg met the eminent Norwegian violinist Ole Bull,[12] who was a family friend; Bull's brother was married to Grieg's aunt.[13] Bull recognized the 15-year-old boy's talent and persuaded his parents to send him to the Leipzig Conservatory,[12] the piano department of which was directed by Ignaz Moscheles.[14]

Grieg enrolled in the conservatory, concentrating on the piano, and enjoyed the many concerts and recitals given in Leipzig. He disliked the discipline of the conservatory course of study. An exception was the organ, which was mandatory for piano students. About his study in the conservatory, he wrote to his biographer, Aimar Grønvold, in 1881: "I must admit, unlike Svendsen, that I left Leipzig Conservatory just as stupid as I entered it. Naturally, I did learn something there, but my individuality was still a closed book to me."[15]

In the spring of 1860, he survived two life-threatening lung diseases, pleurisy and tuberculosis. Throughout his life, Grieg's health was impaired by a destroyed left lung and considerable deformity of his thoracic spine. He suffered from numerous respiratory infections, and ultimately developed combined lung and heart failure. Grieg was admitted many times to spas and sanatoria both in Norway and abroad. Several of his doctors became his friends.[16]

Career

In 1861, Grieg made his debut as a concert pianist in Karlshamn, Sweden. In 1862, he finished his studies in Leipzig and held his first concert in his home town,[17] where his programme included Beethoven's Pathétique sonata.

In 1863, Grieg went to Copenhagen, Denmark, and stayed there for three years. He met the Danish composers J. P. E. Hartmann and Niels Gade. He also met his fellow Norwegian composer Rikard Nordraak (composer of the Norwegian national anthem), who became a good friend and source of inspiration. Nordraak died in 1866, and Grieg composed a funeral march in his honor.[18]

On 11 June 1867, Grieg married his first cousin, Nina Hagerup (1845–1935), a lyric soprano. The next year, their only child, Alexandra, was born. Alexandra died in 1869 from meningitis. In the summer of 1868, Grieg wrote his Piano Concerto in A minor while on holiday in Denmark. Edmund Neupert gave the concerto its premiere performance on 3 April 1869 in the Casino Theatre in Copenhagen. Grieg himself was unable to be there due to conducting commitments in Christiania (now Oslo).[19]

In 1868, Franz Liszt, who had not yet met Grieg, wrote a testimonial for him to the Norwegian Ministry of Education, which led to Grieg's obtaining a travel grant. The two men met in Rome in 1870. On Grieg's first visit, they went over Grieg's Violin Sonata No. 1, which pleased Liszt greatly. On his second visit in April, Grieg brought with him the manuscript of his Piano Concerto, which Liszt proceeded to sightread (including the orchestral arrangement). Liszt's rendition greatly impressed his audience, although Grieg gently pointed out to him that he played the first movement too quickly. Liszt also gave Grieg some advice on orchestration (for example, to give the melody of the second theme in the first movement to a solo trumpet).[20]

In 1874–76, Grieg composed incidental music for the premiere of Henrik Ibsen's play Peer Gynt, at the request of the author.

Grieg had close ties with the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra (Harmonien), and later became Music Director of the orchestra from 1880 to 1882. In 1888, Grieg met Tchaikovsky in Leipzig. Grieg was struck by the greatness of Tchaikovsky.[21] Tchaikovsky thought very highly of Grieg's music, praising its beauty, originality and warmth.[22]

On 6 December 1897, Grieg and his wife performed some of his music at a private concert at Windsor Castle for Queen Victoria and her court.[23]

Grieg was awarded two honorary doctorates, first by the University of Cambridge in 1894 and the next from the University of Oxford in 1906.[24]

Later years

The Norwegian government provided Grieg with a pension as he reached retirement age. In the spring of 1903, Grieg made nine 78-rpm gramophone recordings of his piano music in Paris. All of these discs have been reissued on both LPs and CDs, despite limited fidelity. Grieg recorded player piano music rolls for the Hupfeld Phonola piano-player system and Welte-Mignon reproducing system, all of which survive and can be heard today. He also worked with the Aeolian Company for its 'Autograph Metrostyle' piano roll series wherein he indicated the tempo mapping for many of his pieces.

In 1899, Grieg cancelled his concerts in France in protest of the Dreyfus Affair, an anti-semitic scandal that was then roiling French politics. Regarding this scandal, Grieg had written that he hoped that the French might, "Soon return to the spirit of 1789, when the French republic declared that it would defend basic human rights." As a result of his position on the affair, he became the target of much French hate mail of that day.[25][26]

In 1906, he met the composer and pianist Percy Grainger in London. Grainger was a great admirer of Grieg's music and a strong empathy was quickly established. In a 1907 interview, Grieg stated: "I have written Norwegian Peasant Dances that no one in my country can play, and here comes this Australian who plays them as they ought to be played! He is a genius that we Scandinavians cannot do other than love."[27]

Edvard Grieg died at the Municipal Hospital in Bergen, Norway, on 4 September 1907 at age 64 from heart failure. He had suffered a long period of illness. His last words were "Well, if it must be so."

The funeral drew between 30,000 and 40,000 people to the streets of his home town to honor him. Following his wish, his own Funeral March in Memory of Rikard Nordraak was played with orchestration by his friend Johan Halvorsen, who had married Grieg's niece. In addition, the Funeral March movement from Chopin's Piano Sonata No. 2 was played. Grieg was cremated, and his ashes were entombed in a mountain crypt near his house, Troldhaugen. After the death of his wife, her ashes were placed alongside his.[6]

Edvard Grieg and his wife were Unitarians and Nina attended the Unitarian church in Copenhagen after his death.[28][29]

A century after his death, Grieg's legacy extends beyond the field of music. There is a large statue of Grieg in Seattle, while one of the largest hotels in Bergen (his hometown) is named Quality Hotel Edvard Grieg (with over 370 rooms), and a large crater on the planet Mercury is named after Grieg.

Music

Some of Grieg's early works include a symphony (which he later suppressed) and a piano sonata. He also wrote three violin sonatas and a cello sonata.[6]

Grieg also composed the incidental music for Henrik Ibsen's play Peer Gynt, which includes the famous excerpt titled, "In the Hall of the Mountain King". In this piece of music, the adventures of the anti-hero, Peer Gynt, are related, including the episode in which he steals a bride at her wedding. The angry guests chase him, and Peer falls, hitting his head on a rock. He wakes up in a mountain surrounded by trolls. The music of "In the Hall of the Mountain King" represents the angry trolls taunting Peer and gets louder each time the theme repeats. The music ends with Peer escaping from the mountain.

In an 1874 letter to his friend Frants Beyer, Grieg expressed his unhappiness with Dance of the Mountain King's Daughter, one of the movements he composed for Peer Gynt, writing "I have also written something for the scene in the hall of the mountain King – something that I literally can't bear listening to because it absolutely reeks of cow-pies, exaggerated Norwegian nationalism, and trollish self-satisfaction! But I have a hunch that the irony will be discernible."[30]

Grieg's Holberg Suite was originally written for the piano, and later arranged by the composer for string orchestra. Grieg wrote songs in which he set lyrics by poets Heinrich Heine, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Henrik Ibsen, Hans Christian Andersen, Rudyard Kipling and others. Russian composer Nikolai Myaskovsky used a theme by Grieg for the variations with which he closed his Third String Quartet. Norwegian pianist Eva Knardahl recorded the composer's complete piano music on 13 LPs for BIS Records from 1977 to 1980. The recordings were reissued in 2006 on 12 compact discs, also on BIS Records. Grieg himself recorded many of these piano works before his death in 1907.

List of selected works

- Piano Sonata in E minor, Op. 7

- Violin Sonata No. 1 in F major, Op. 8

- Concert Overture In Autumn, Op. 11

- Violin Sonata No. 2 in G major, Op. 13

- Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16

- Incidental music to Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson's play Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op. 22

- Incidental music to Henrik Ibsen's play Peer Gynt, Op. 23

- Ballade in the Form of Variations on a Norwegian Folk Song in G minor, Op. 24

- String Quartet in G minor, Op. 27

- Two Elegiac Melodies for strings or piano, Op. 34

- Four Norwegian Dances for piano four hands, Op. 35 (better known in orchestrations by Hans Sitt and others)

- Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36

- Holberg Suite for piano, later arr. for string orchestra, Op. 40

- Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45

- Peer Gynt Suite No. 1, Op. 46

- Lyric Suite for orchestra, Op. 54 (orchestration of four Lyric Pieces)

- Peer Gynt Suite No. 2, Op. 55

- Four Symphonic Dances for piano, later arr. for orchestra, Op. 64

- Haugtussa Song Cycle after Arne Garborg, Op. 67

- Sixty-six Lyric Pieces for piano in ten books, Opp. 12, 38, 43, 47, 54, 57, 62, 65, 68 and 71, including: Arietta, To the Spring, Little Bird, Butterfly, Notturno, Wedding Day at Troldhaugen, At Your Feet, Longing For Home, March of the Dwarfs, Poème érotique and Gone.

See also

- Bust of Edvard Grieg, University of Washington, Seattle

- Grieg (crater)

- Grieg's music in popular culture

- Peer Gynt Prize

- Song of Norway

References

Notes

- Daniel M. Grimley (2006). Grieg: Music, Landscape and Norwegian Identity. Ipswich: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-210-0.

- "Grieghallen". Bergen byleksikon. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "Griegakademiet". Universitetet i Bergen. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "Edvard Grieg Museum Troldhaugen". KODE. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "About Edvard Grieg Kor". Edvard Grieg Kor. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Benestad, Finn. "Edvard Grieg". In Helle, Knut (ed.). Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- Benestad & Schjelderup-Ebbe 1990, pp. 25–28.

- "The Origins of the Greig Family Name". www.greig.org. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Nils Grinde. "Grieg, Edvard", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 11 November 2013 (subscription required)

- Bazzana, Kevin (2003). Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7710-1101-6. OCLC 52286240.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robert Layton. Grieg. (London: Omnibus Press, 1998)

- Benestad & Schjelderup-Ebbe 1990, pp. 35–36

- Benestad & Schjelderup-Ebbe 1990, p. 24.

- Jerome Roche and Henry Roche. "Moscheles, Ignaz", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press, accessed 30 June 2014 (subscription required)

- "Edvard Grieg – Leipzig Conservatory", The Fryderyk Chopin Institute

- Laerum, OD (December 1993). "Edvard Grieg's health and his physicians". Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 113 (30): 3750–3. PMID 8278965.

- Grieg Museum

- Rune J. Andersen. "Edvard Grieg". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Inger Elisabeth Haavet. "Nina Grieg". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Harald Herresthal. "Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)". Norwegian State Academy of Music in Oslo. Archived from the original on 14 December 2005. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- Gretchen Lamb. "First Impressions, Edvard Grieg". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2006.CS1 maint: unfit url (link) Lamb cites David Brown's Tchaikovsky Remembered

- Richard Freed. "Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16". Archived from the original on 1 November 2006. Retrieved 11 October 2006.

- Mallet, Victor (1968). Life With Queen Victoria. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 120.

- Carley, Lionel. "Preface." Preface. Edvard Grieg in England. N.p.: Boydell, 2006. Xi. Google Books. Web. 01 June 2014.

- "Grieg the Humanist Brought to Light", Dagbladet

- "I Have No Desire..." Haaretz. April 4, 2002. By Shaul Koubovi. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- John Bird, Percy Grainger, Oxford University Press, 1999, pp. 133–134.

- Peter Hughes (4 November 2004). "Edvard and Nina Grieg". Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. Unitarian Universalist Association. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- Leah Kennedy (1 May 2011). "The Life and Works of Edvard Grieg". Utah State University. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- Layton, Robert (1998). Grieg: Illustrated Lives of the Great Composers. Omnibus Press. p. 75. ISBN 0-7119-4811-9. See also: Tommasini, Anthony (16 September 2007). "Respect at Last for Grieg?". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

Bibliography

- Benestad, Finn; Schjelderup-Ebbe, Dag (1990) [1980]. Edvard Grieg – mennesket og kunstneren (in Norwegian) (2 ed.). Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-03-16373-4.

Further reading

English

- Carley, Lionel (2006) Edvard Grieg in England (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press) ISBN 1-84383-207-0

- Finck, Henry Theophilius (2008) Edvard Grieg (Bastian Books) ISBN 978-0-554-96326-6

- Finck, Henry Theophilus (2002) Edvard Grieg; with an introductory note by Lothar Feinstein (Adelaide: London Cambridge Scholars Press) ISBN 1-904303-20-X

- Foster, Beryl (2007) Songs of Edvard Grieg (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press) ISBN 1-84383-343-3

- Grimley, Daniel (2007) Grieg: Music, Landscape and Norwegian Cultural Identity (Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press) ISBN 1-84383-210-0

- Jarrett, Sandra (2003) Edvard Grieg and his songs (Aldershot: Ashgate) ISBN 0-7546-3003-X.

- Kijas, Anna E. (2013). ""A suitale soloist for my piano concerto": Teresa Carreño as a promoter of Edvard Grieg's music". Notes: Quarterly Journal of the Music Library Association. Music Library Association. 70 (1): 37–58. doi:10.1353/not.2013.0121.

Norwegian

- Bredal, Dag/Strøm-Olsen, Terje (1992) Edvard Grieg – Musikken er en kampplass (Oslo: Aventura Forlag A/S) ISBN 82-588-0890-7

- Dahl Jr., Erling (2007) Edvard Grieg – En introduksjon til hans liv og musikk (Bergen: Vigmostad og Bjørke) ISBN 978-82-419-0418-9

- Purdy, Claire Lee (1968) Historien om Edvard Grieg (Oslo: A/S Forlagshuse) ISBN 82-511-0152-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edvard Grieg. |

- Grieg 2007 Official Site for 100th year commemoration of Edvard Grieg

- The Grieg archives at Bergen Public Library

- Troldhaugen Museum, Grieg's home

- Biography of Grieg by prof. Harald Herresthal

- Works by Edvard Grieg at Open Library

- Edvard Grieg statue by Sigvald Asbjørnsen Prospect Park (Brooklyn)

- Films about Grieg's life: What Price Immortality? (1999), Song of Norway (1970)

- Edvard Grieg picture collection at flickr commons

- Edvard and Nina Grieg, Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

Recordings by Grieg

- Papillon – Lyric Piece, Op. 43, no. 1 as recorded by Grieg on piano roll, 17 April 1906, Leipzig (Info)

- Legendary Piano Recordings: The Complete Grieg, Saint-Saëns, Pugno, and Diémer (Marston Records)

- Edvard Grieg: The Piano Music In Historic Interpretations (SIMAX Classics – PSC1809)

- Grieg and his Circle (Pearl, GEMM 9933 CD)

- Grieg spiller Grieg (Edvard Grieg Museum Troldhaugen) (in Norwegian)

- Piano Rolls (The Reproducing Piano Roll Foundation)

Recordings of Grieg works

- Edvard Grieg, Sonata No. 1 in F major, I. Allegro con brio – Gregory Maytan (violin), Nicole Lee (piano)

- Edvard Grieg, Sonata No. 1 in F major, II. Allegretto quasi Andantino – Gregory Maytan (violin), Nicole Lee (piano)

- Edvard Grieg, Sonata No. 1 in F major, III. Allegro molto vivace – Gregory Maytan (violin), Nicole Lee (piano)

- Edvard Grieg, Sonata No. 3 in C minor, I. Allegro molto ed appasionato – Gregory Maytan (violin), Nicole Lee (piano)

- Edvard Grieg, Sonata No. 3 in C minor, II. Allegretto espressivo all Ramanza – Gregory Maytan (violin), Nicole Lee (piano)

- Edvard Grieg, Sonata No. 3 in C minor, III. Allegro animato – Gregory Maytan (violin), Nicole Lee (piano)

Music scores

- Free scores by Edvard Grieg at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Edvard Grieg in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores at the Mutopia Project