Groundwater

Groundwater is the water present beneath Earth's surface in soil pore spaces and in the fractures of rock formations. A unit of rock or an unconsolidated deposit is called an aquifer when it can yield a usable quantity of water. The depth at which soil pore spaces or fractures and voids in rock become completely saturated with water is called the water table. Groundwater is recharged from the surface; it may discharge from the surface naturally at springs and seeps, and can form oases or wetlands. Groundwater is also often withdrawn for agricultural, municipal, and industrial use by constructing and operating extraction wells. The study of the distribution and movement of groundwater is hydrogeology, also called groundwater hydrology.

Typically, groundwater is thought of as water flowing through shallow aquifers, but, in the technical sense, it can also contain soil moisture, permafrost (frozen soil), immobile water in very low permeability bedrock, and deep geothermal or oil formation water. Groundwater is hypothesized to provide lubrication that can possibly influence the movement of faults. It is likely that much of Earth's subsurface contains some water, which may be mixed with other fluids in some instances. Groundwater may not be confined only to Earth. The formation of some of the landforms observed on Mars may have been influenced by groundwater. There is also evidence that liquid water may also exist in the subsurface of Jupiter's moon Europa.[1]

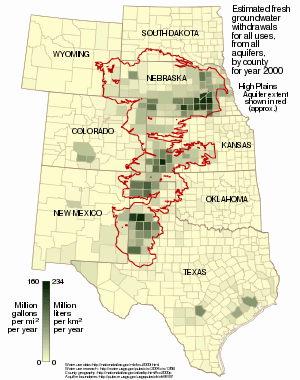

Groundwater is often cheaper, more convenient and less vulnerable to pollution than surface water. Therefore, it is commonly used for public water supplies. For example, groundwater provides the largest source of usable water storage in the United States, and California annually withdraws the largest amount of groundwater of all the states.[2] Underground reservoirs contain far more water than the capacity of all surface reservoirs and lakes in the US, including the Great Lakes. Many municipal water supplies are derived solely from groundwater.[3]

Polluted groundwater is less visible and more difficult to clean up than pollution in rivers and lakes. Groundwater pollution most often results from improper disposal of wastes on land. Major sources include industrial and household chemicals and garbage landfills, excessive fertilizers and pesticides used in agriculture, industrial waste lagoons, tailings and process wastewater from mines, industrial fracking, oil field brine pits, leaking underground oil storage tanks and pipelines, sewage sludge and septic systems.

Aquifers

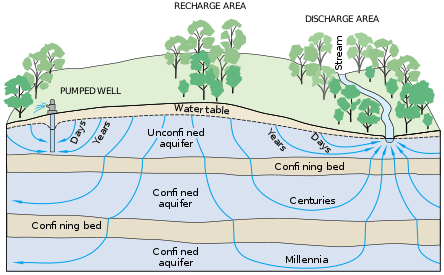

An aquifer is a layer of porous substrate that contains and transmits groundwater. When water can flow directly between the surface and the saturated zone of an aquifer, the aquifer is unconfined. The deeper parts of unconfined aquifers are usually more saturated since gravity causes water to flow downward.

The upper level of this saturated layer of an unconfined aquifer is called the water table or phreatic surface. Below the water table, where in general all pore spaces are saturated with water, is the phreatic zone.

Substrate with low porosity that permits limited transmission of groundwater is known as an aquitard. An aquiclude is a substrate with porosity that is so low it is virtually impermeable to groundwater.

A confined aquifer is an aquifer that is overlain by a relatively impermeable layer of rock or substrate such as an aquiclude or aquitard. If a confined aquifer follows a downward grade from its recharge zone, groundwater can become pressurized as it flows. This can create artesian wells that flow freely without the need of a pump and rise to a higher elevation than the static water table at the above, unconfined, aquifer.

The characteristics of aquifers vary with the geology and structure of the substrate and topography in which they occur. In general, the more productive aquifers occur in sedimentary geologic formations. By comparison, weathered and fractured crystalline rocks yield smaller quantities of groundwater in many environments. Unconsolidated to poorly cemented alluvial materials that have accumulated as valley-filling sediments in major river valleys and geologically subsiding structural basins are included among the most productive sources of groundwater.

The high specific heat capacity of water and the insulating effect of soil and rock can mitigate the effects of climate and maintain groundwater at a relatively steady temperature. In some places where groundwater temperatures are maintained by this effect at about 10 °C (50 °F), groundwater can be used for controlling the temperature inside structures at the surface. For example, during hot weather relatively cool groundwater can be pumped through radiators in a home and then returned to the ground in another well. During cold seasons, because it is relatively warm, the water can be used in the same way as a source of heat for heat pumps that is much more efficient than using air.

The volume of groundwater in an aquifer can be estimated by measuring water levels in local wells and by examining geologic records from well-drilling to determine the extent, depth and thickness of water-bearing sediments and rocks. Before an investment is made in production wells, test wells may be drilled to measure the depths at which water is encountered and collect samples of soils, rock and water for laboratory analyses. Pumping tests can be performed in test wells to determine flow characteristics of the aquifer.[3]

Water cycle

Groundwater makes up about thirty percent of the world's fresh water supply, which is about 0.76% of the entire world's water, including oceans and permanent ice.[4][5] Global groundwater storage is roughly equal to the total amount of freshwater stored in the snow and ice pack, including the north and south poles. This makes it an important resource that can act as a natural storage that can buffer against shortages of surface water, as in during times of drought.[6]

Groundwater is naturally replenished by surface water from precipitation, streams, and rivers when this recharge reaches the water table.[7]

Groundwater can be a long-term 'reservoir' of the natural water cycle (with residence times from days to millennia),[8][9] as opposed to short-term water reservoirs like the atmosphere and fresh surface water (which have residence times from minutes to years). The figure[10] shows how deep groundwater (which is quite distant from the surface recharge) can take a very long time to complete its natural cycle.

The Great Artesian Basin in central and eastern Australia is one of the largest confined aquifer systems in the world, extending for almost 2 million km2. By analysing the trace elements in water sourced from deep underground, hydrogeologists have been able to determine that water extracted from these aquifers can be more than 1 million years old.

By comparing the age of groundwater obtained from different parts of the Great Artesian Basin, hydrogeologists have found it increases in age across the basin. Where water recharges the aquifers along the Eastern Divide, ages are young. As groundwater flows westward across the continent, it increases in age, with the oldest groundwater occurring in the western parts. This means that in order to have travelled almost 1000 km from the source of recharge in 1 million years, the groundwater flowing through the Great Artesian Basin travels at an average rate of about 1 metre per year.

Recent research has demonstrated that evaporation of groundwater can play a significant role in the local water cycle, especially in arid regions.[11] Scientists in Saudi Arabia have proposed plans to recapture and recycle this evaporative moisture for crop irrigation. In the opposite photo, a 50-centimeter-square reflective carpet, made of small adjacent plastic cones, was placed in a plant-free dry desert area for five months, without rain or irrigation. It managed to capture and condense enough ground vapor to bring to life naturally buried seeds underneath it, with a green area of about 10% of the carpet area. It is expected that, if seeds were put down before placing this carpet, a much wider area would become green.[12]

Issues

Overview

Certain problems have beset the use of groundwater around the world. Just as river waters have been over-used and polluted in many parts of the world, so too have aquifers. The big difference is that aquifers are out of sight. The other major problem is that water management agencies, when calculating the "sustainable yield" of aquifer and river water, have often counted the same water twice, once in the aquifer, and once in its connected river. This problem, although understood for centuries, has persisted, partly through inertia within government agencies. In Australia, for example, prior to the statutory reforms initiated by the Council of Australian Governments water reform framework in the 1990s, many Australian states managed groundwater and surface water through separate government agencies, an approach beset by rivalry and poor communication.

In general, the time lags inherent in the dynamic response of groundwater to development have been ignored by water management agencies, decades after scientific understanding of the issue was consolidated. In brief, the effects of groundwater overdraft (although undeniably real) may take decades or centuries to manifest themselves. In a classic study in 1982, Bredehoeft and colleagues[13] modeled a situation where groundwater extraction in an intermontane basin withdrew the entire annual recharge, leaving ‘nothing’ for the natural groundwater-dependent vegetation community. Even when the borefield was situated close to the vegetation, 30% of the original vegetation demand could still be met by the lag inherent in the system after 100 years. By year 500, this had reduced to 0%, signalling complete death of the groundwater-dependent vegetation. The science has been available to make these calculations for decades; however, in general water management agencies have ignored effects that will appear outside the rough timeframe of political elections (3 to 5 years). Marios Sophocleous[13] argued strongly that management agencies must define and use appropriate timeframes in groundwater planning. This will mean calculating groundwater withdrawal permits based on predicted effects decades, sometimes centuries in the future.

As water moves through the landscape, it collects soluble salts, mainly sodium chloride. Where such water enters the atmosphere through evapotranspiration, these salts are left behind. In irrigation districts, poor drainage of soils and surface aquifers can result in water tables' coming to the surface in low-lying areas. Major land degradation problems of soil salinity and waterlogging result,[14] combined with increasing levels of salt in surface waters. As a consequence, major damage has occurred to local economies and environments.[15]

Four important effects are worthy of brief mention. First, flood mitigation schemes, intended to protect infrastructure built on floodplains, have had the unintended consequence of reducing aquifer recharge associated with natural flooding. Second, prolonged depletion of groundwater in extensive aquifers can result in land subsidence, with associated infrastructure damage – as well as, third, saline intrusion.[16] Fourth, draining acid sulphate soils, often found in low-lying coastal plains, can result in acidification and pollution of formerly freshwater and estuarine streams.[17]

Another cause for concern is that groundwater drawdown from over-allocated aquifers has the potential to cause severe damage to both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems – in some cases very conspicuously but in others quite imperceptibly because of the extended period over which the damage occurs.[18]

Overdraft

Groundwater is a highly useful and often abundant resource. However, over-use, over-abstraction or overdraft, can cause major problems to human users and to the environment. The most evident problem (as far as human groundwater use is concerned) is a lowering of the water table beyond the reach of existing wells. As a consequence, wells must be drilled deeper to reach the groundwater; in some places (e.g., California, Texas, and India) the water table has dropped hundreds of feet because of extensive well pumping.[19] In the Punjab region of India, for example, groundwater levels have dropped 10 meters since 1979, and the rate of depletion is accelerating.[20] A lowered water table may, in turn, cause other problems such as groundwater-related subsidence and saltwater intrusion.

Groundwater is also ecologically important. The importance of groundwater to ecosystems is often overlooked, even by freshwater biologists and ecologists. Groundwaters sustain rivers, wetlands, and lakes, as well as subterranean ecosystems within karst or alluvial aquifers.

Not all ecosystems need groundwater, of course. Some terrestrial ecosystems – for example, those of the open deserts and similar arid environments – exist on irregular rainfall and the moisture it delivers to the soil, supplemented by moisture in the air. While there are other terrestrial ecosystems in more hospitable environments where groundwater plays no central role, groundwater is in fact fundamental to many of the world's major ecosystems. Water flows between groundwaters and surface waters. Most rivers, lakes, and wetlands are fed by, and (at other places or times) feed groundwater, to varying degrees. Groundwater feeds soil moisture through percolation, and many terrestrial vegetation communities depend directly on either groundwater or the percolated soil moisture above the aquifer for at least part of each year. Hyporheic zones (the mixing zone of streamwater and groundwater) and riparian zones are examples of ecotones largely or totally dependent on groundwater.

Subsidence

Subsidence occurs when too much water is pumped out from underground, deflating the space below the above-surface, and thus causing the ground to collapse. The result can look like craters on plots of land. This occurs because, in its natural equilibrium state, the hydraulic pressure of groundwater in the pore spaces of the aquifer and the aquitard supports some of the weight of the overlying sediments. When groundwater is removed from aquifers by excessive pumping, pore pressures in the aquifer drop and compression of the aquifer may occur. This compression may be partially recoverable if pressures rebound, but much of it is not. When the aquifer gets compressed, it may cause land subsidence, a drop in the ground surface. The city of New Orleans, Louisiana is actually below sea level today, and its subsidence is partly caused by removal of groundwater from the various aquifer/aquitard systems beneath it.[21] In the first half of the 20th century, the San Joaquin Valley experienced significant subsidence, in some places up to 8.5 metres (28 feet)[22] due to groundwater removal. Cities on river deltas, including Venice in Italy,[23] and Bangkok in Thailand,[24] have experienced surface subsidence; Mexico City, built on a former lake bed, has experienced rates of subsidence of up to 40 cm (1'3") per year.[25]

Seawater intrusion

Seawater intrusion is the flow or presence of seawater into coastal aquifers; it is a case of saltwater intrusion. It is a natural phenomenon but can be caused or worsened by anthropogenic factors. In the case of homogeneous aquifers, seawater intrusion forms a saline wedge below a transition zone to fresh groundwater, flowing seward on the top,.[26][27]

Pollution

Polluted groundwater is less visible, but more difficult to clean up, than pollution in rivers and lakes. Groundwater pollution most often results from improper disposal of wastes on land. Major sources include industrial and household chemicals and garbage landfills, industrial waste lagoons, tailings and process wastewater from mines, oil field brine pits, leaking underground oil storage tanks and pipelines, sewage sludge and septic systems. Polluted groundwater is mapped by sampling soils and groundwater near suspected or known sources of pollution, to determine the extent of the pollution, and to aid in the design of groundwater remediation systems. Preventing groundwater pollution near potential sources such as landfills requires lining the bottom of a landfill with watertight materials, collecting any leachate with drains, and keeping rainwater off any potential contaminants, along with regular monitoring of nearby groundwater to verify that contaminants have not leaked into the groundwater.[3]

Groundwater pollution, from pollutants released to the ground that can work their way down into groundwater, can create a contaminant plume within an aquifer. Pollution can occur from landfills, naturally occurring arsenic, on-site sanitation systems or other point sources, such as petrol stations with leaking underground storage tanks, or leaking sewers.

Movement of water and dispersion within the aquifer spreads the pollutant over a wider area, its advancing boundary often called a plume edge, which can then intersect with groundwater wells or daylight into surface water such as seeps and springs, making the water supplies unsafe for humans and wildlife. Different mechanism have influence on the transport of pollutants, e.g. diffusion, adsorption, precipitation, decay, in the groundwater. The interaction of groundwater contamination with surface waters is analyzed by use of hydrology transport models.

The danger of pollution of municipal supplies is minimized by locating wells in areas of deep groundwater and impermeable soils, and careful testing and monitoring of the aquifer and nearby potential pollution sources.[3]

Arsenic and fluoride

Around one-third of the world's population drinks water from groundwater resources. Of this, about 10 percent, approximately 300 million people, obtains water from groundwater resources that are heavily polluted with arsenic or fluoride.[28] These trace elements derive mainly from natural sources by leaching from rock and sediments.

New method of identifying substances that are hazardous to health

In 2008, the Swiss Aquatic Research Institute, Eawag, presented a new method by which hazard maps could be produced for geogenic toxic substances in groundwater.[29][30][31][32] This provides an efficient way of determining which wells should be tested.

In 2016, the research group made its knowledge freely available on the Groundwater Assessment Platform GAP. This offers specialists worldwide the possibility of uploading their own measurement data, visually displaying them and producing risk maps for areas of their choice. GAP also serves as a knowledge-sharing forum for enabling further development of methods for removing toxic substances from water.

Regulations

United States

In the United States, laws regarding ownership and use of groundwater are generally state laws; however, regulation of groundwater to minimize pollution of groundwater is by both states and the federal-level Environmental Protection Agency. Ownership and use rights to groundwater typically follow one of three main systems:[33]

- The Rule of Capture provides each landowner the ability to capture as much groundwater as they can put to a beneficial use, but they are not guaranteed any set amount of water. As a result, well-owners are not liable to other landowners for taking water from beneath their land. State laws or regulations will often define "beneficial use", and sometimes place other limits, such as disallowing groundwater extraction which causes subsidence on neighboring property.

- Limited private ownership rights similar to riparian rights in a surface stream. The amount of groundwater right is based on the size of the surface area where each landowner gets a corresponding amount of the available water. Once adjudicated, the maximum amount of the water right is set, but the right can be decreased if the total amount of available water decreases as is likely during a drought. Landowners may sue others for encroaching upon their groundwater rights, and water pumped for use on the overlying land takes preference over water pumped for use off the land.

- In November 2006, the Environmental Protection Agency published the groundwater Rule in the United States Federal Register. The EPA was worried that the groundwater system would be vulnerable to contamination from fecal matter. The point of the rule was to keep microbial pathogens out of public water sources.[34] The 2006 groundwater Rule was an amendment of the 1996 Safe Drinking Water Act.

Other rules in the United States include:

- Reasonable Use Rule (American Rule): This rule does not guarantee the landowner a set amount of water, but allows unlimited extraction as long as the result does not unreasonably damage other wells or the aquifer system. Usually this rule gives great weight to historical uses and prevents new uses that interfere with the prior use.

- Groundwater scrutiny upon real estate property transactions in the US: In the US, upon commercial real estate property transactions both groundwater and soil are the subjects of scrutiny. For brownfields sites (formerly contaminated sites that have been remediated), Phase I Environmental Site Assessments are typically prepared, to investigate and disclose potential pollution issues.[35] In the San Fernando Valley of California, real estate contracts for property transfer below the Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL) and eastward have clauses releasing the seller from liability for groundwater contamination consequences from existing or future pollution of the Valley Aquifer.

India

In India, 65% of the irrigation is from groundwater.[36] The groundwater regulation is controlled and maintained by the central government and four organizations; 1) Central Water Commission, 2) Central Ground Water, 3) Central Ground Water Authority, 4) Central Pollution Control Board.[37]

Laws, regulations and scheme regarding India's groundwater:

- 2019 Atal Bhujal Yojana (Atal groundwater scheme), a 5 years (2020-21 to 2024-25) scheme costing INR 6 billion (US$854 million) for managing demand side with village panchayat level water security plans, was approved for implementation 8,350 water-stressed villages across 7 states, including Haryana, Gujarat, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh.[38]

- 2013 National Water Framework Bill ensures that India's groundwater is a public resource, and is not to be exploited by companies through privatization of water. The National Water Framework Bill allows for everyone to access clean drinking water, of the right to clean drinking water under Article 21 of 'Right to Life' in India's Constitution. The bill indicates a want for the states of India to have full control of groundwater contained in aquifers. So far Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Karnataka, Kerala, West Bengal, Telangana, Maharashtra, Lakshadweep, Puducherry, Chandigarh, Dadra & Nagar Haveli are the only ones using this bill.[37]

- In 2012, National Water Policy was updated, which had previously been launched in 1987 and updated in 2002 and later in 2012.[39]

- In 2011, the Indian Government created a Model Bill for Groundwater Management; this model selects which state governments can enforce their laws on groundwater usage and regulation.

- 1882 Easement Act gives landowners priority over surface and groundwater that is on their land and allows them to give or take as much as they want as long as the water is on their land. This act prevents the government from enforcing regulations of groundwater, allowing many landowners to privatize their groundwater instead accessing it in community areas. 1882 Easement Act's Section 7(g) states that every landowner has the right to collect within his limits, all water under the land and on its surface which does not pass in a defined channel.[37]

Canada

A significant portion of Canada’s population relies on the use of groundwater. In Canada, roughly 8.9 million people or 30% of Canada's population rely on groundwater for domestic use and approximately two thirds of these users live in rural areas.[40]

- The Constitution Act, 1867, does not give authority over groundwater to either order of Canadian government; therefore, the matter largely falls under provincial jurisdiction

- Federal and Provincial governments can share responsibilities when dealing with agriculture, health, inter-provincial waters and national water-related issues.

- Federal jurisdiction in areas as boundary/trans-boundary waters, fisheries, navigation, and water on federal lands, First Nations reserves and in Territories.

- Federal jurisdiction over groundwater when aquifers cross inter-provincial or international boundaries.

A large federal government groundwater initiative is the development of the multi-barrier approach. The multi-barrier approach is a system of processes to prevent the deterioration of drinking water from the source. The multi-barrier consists of three key elements:

- Source water protection,

- Drinking water treatment, and

- Drinking water distribution systems.[41]

Iran

According to The Law of Distribution of Water (5th chapter), these items are crime (punishment :10 to 50 lashes or from 15 days to three months imprisonment):[42]

- Person who does well digging for accessing water.

- Person who extracts from groundwater.

See also

- Baseflow

- Groundwater-dependent ecosystems

- Groundwater banking

- Groundwater flow

- Groundwater model

- Seep (hydrology)

- Spring (hydrology) – Point at which water emerges from an aquifer to the surface

- Water well

- Water table – Top of a saturated aquifer, or where the water pressure head is equal to the atmospheric pressure

References

- Richard Greenburg (2005). The Ocean Moon: Search for an Alien Biosphere. Springer Praxis Books.

- National Geographic Almanac of Geography, 2005, ISBN 0-7922-3877-X, p. 148.

- "What is hydrology and what do hydrologists do?". The USGS Water Science School. United States Geological Survey. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 21 Jan 2014.

- "Where is Earth's Water?". www.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2020-03-18.

- Gleick, P. H. (1993). Water in crisis. Pacific Institute for Studies in Dev., Environment & Security. Stockholm Env. Institute, Oxford Univ. Press. 473p, 9.

- "Learn More: Groundwater". Columbia Water Center. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- United States Department of the Interior (1977). Ground Water Manual (First ed.). United States Government Printing Office. p. 4.

- Bethke, Craig M.; Johnson, Thomas M. (May 2008). "Groundwater Age and Groundwater Age Dating". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 36 (1): 121–152. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.36.031207.124210. ISSN 0084-6597.

- Gleeson, Tom; Befus, Kevin M.; Jasechko, Scott; Luijendijk, Elco; Cardenas, M. Bayani (February 2016). "The global volume and distribution of modern groundwater". Nature Geoscience. 9 (2): 161–167. doi:10.1038/ngeo2590. ISSN 1752-0894.

- File:Groundwater flow.svg

- Hassan, SM Tanvir (March 2008). Assessment of groundwater evaporation through groundwater model with spatio-temporally variable fluxes (PDF) (MSc). Enschede, Netherlands: International Institute for Geo-Information Science and Earth Observation.

- Al-Kasimi, S. M. (2002). Existence of Ground Vapor-Flux Up-Flow: Proof & Utilization in Planting The Desert Using Reflective Carpet. 3. Dahran. pp. 105–19.

- Sophocleous, Marios (2002). "Interactions between groundwater and surface water: the state of the science". Hydrogeology Journal. 10 (1): 52–67. Bibcode:2002HydJ...10...52S. doi:10.1007/s10040-001-0170-8.

- "Free articles and software on drainage of waterlogged land and soil salinity control". Retrieved 2010-07-28.

- Ludwig, D.; Hilborn, R.; Walters, C. (1993). "Uncertainty, Resource Exploitation, and Conservation: Lessons from History" (PDF). Science. 260 (5104): 17–36. Bibcode:1993Sci...260...17L. doi:10.1126/science.260.5104.17. JSTOR 1942074. PMID 17793516. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-08-26. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- Zektser et al.

- Sommer, Bea; Horwitz, Pierre; Sommer, Bea; Horwitz, Pierre (2001). "Water quality and macroinvertebrate response to acidification following intensified summer droughts in a Western Australian wetland". Marine and Freshwater Research. 52 (7): 1015. doi:10.1071/MF00021.

- Zektser, S.; LoaIciga, H. A.; Wolf, J. T. (2004). "Environmental impacts of groundwater overdraft: selected case studies in the southwestern United States". Environmental Geology. 47 (3): 396–404. doi:10.1007/s00254-004-1164-3.

- Perrone, Debra; Jasechko, Scott (August 2019). "Deeper well drilling an unsustainable stopgap to groundwater depletion". Nature Sustainability. 2 (8): 773–782. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0325-z. ISSN 2398-9629.

- Upmanu Lall. "Punjab: A tale of prosperity and decline". Columbia Water Center. Retrieved 2009-09-11.

- Dokka, Roy K. (2011). "The role of deep processes in late 20th century subsidence of New Orleans and coastal areas of southern Louisiana and Mississippi". Journal of Geophysical Research. 116 (B6): B06403. Bibcode:2011JGRB..116.6403D. doi:10.1029/2010JB008008. ISSN 0148-0227.

- Sneed, M; Brandt, J; Solt, M (2013). "Land Subsidence along the Delta-Mendota Canal in the Northern Part of the San Joaquin Valley, California, 2003–10" (PDF). USGS Scientific Investigations Report 2013-5142. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Tosi, Luigi; Teatini, Pietro; Strozzi, Tazio; Da Lio, Cristina (2014). "Relative Land Subsidence of the Venice Coastland, Italy". Engineering Geology for Society and Territory – Volume 4. pp. 171–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-08660-6_32. ISBN 978-3-319-08659-0.

- Aobpaet, Anuphao; Cuenca, Miguel Caro; Hooper, Andrew; Trisirisatayawong, Itthi (2013). "InSAR time-series analysis of land subsidence in Bangkok, Thailand". International Journal of Remote Sensing. 34 (8): 2969–82. doi:10.1080/01431161.2012.756596. ISSN 0143-1161.

- Arroyo, Danny; Ordaz, Mario; Ovando-Shelley, Efrain; Guasch, Juan C.; Lermo, Javier; Perez, Citlali; Alcantara, Leonardo; Ramírez-Centeno, Mario S. (2013). "Evaluation of the change in dominant periods in the lake-bed zone of Mexico City produced by ground subsidence through the use of site amplification factors". Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 44: 54–66. doi:10.1016/j.soildyn.2012.08.009. ISSN 0267-7261.

- Polemio, M.; Dragone, V.; Limoni, P.P. (2009). "Monitoring and methods to analyse the groundwater quality degradation risk in coastal karstic aquifers (Apulia, Southern Italy)". Environmental Geology. 58 (2): 299–312. doi:10.1007/s00254-008-1582-8.

- Fleury, P.; Bakalowicz, M.; De Marsily, G. (2007). "Submarine springs and coastal karst aquifers: a review". Journal of Hydrology. 339 (1–2): 79–92. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2007.03.009.

- Eawag (2015) Geogenic Contamination Handbook – Addressing Arsenic and Fluoride in Drinking Water. C.A. Johnson, A. Bretzler (Eds.), Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf, Switzerland. (download: www.eawag.ch/en/research/humanwelfare/drinkingwater/wrq/geogenic-contamination-handbook/)

- Amini, M.; Mueller, K.; Abbaspour, K.C.; Rosenberg, T.; Afyuni, M.; Møller, M.; Sarr, M.; Johnson, C.A. (2008) Statistical modeling of global geogenic fluoride contamination in groundwaters. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(10), 3662–68, doi:10.1021/es071958y

- Amini, M.; Abbaspour, K.C.; Berg, M.; Winkel, L.; Hug, S.J.; Hoehn, E.; Yang, H.; Johnson, C.A. (2008). “Statistical modeling of global geogenic arsenic contamination in groundwater”. Environmental Science and Technology 42 (10), 3669–75. doi:10.1021/es702859e

- Winkel, L.; Berg, M.; Amini, M.; Hug, S.J.; Johnson, C.A. Predicting groundwater arsenic contamination in Southeast Asia from surface parameters. Nature Geoscience, 1, 536–42 (2008). doi:10.1038/ngeo254

- Rodríguez-Lado, L.; Sun, G.; Berg, M.; Zhang, Q.; Xue, H.; Zheng, Q.; Johnson, C.A. (2013) Groundwater arsenic contamination throughout China. Science, 341(6148), 866–68, doi:10.1126/science.1237484

- "Appendix H, Groundwater Law and Regulated Riparianism" (PDF), Final Report: Restoring Great Lakes Basin Water thorough the Use of Conservation Credits and Integrated Water Balance Analysis System, The Great Lakes Protection Fund Project # 763, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011, retrieved 16 January 2014

- Ground Water Rule (GWR) | Ground Water Rule | US EPA. Water.epa.gov. Retrieved on 2011-06-09.

- EPA; "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2011-09-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- PM Launches Rs 6,000 Crore Groundwater Management Plan, NDTV, 25 December 2019.

- Suhag, Roopal (February 2016). "Overview of Groundwater in India" (PDF). PRS India.org. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- Centre approves Rs 6,000 crore scheme to manage groundwater, Times of India, 24 December 2019.

- "National Water Policy 2002" (PDF). Ministry of Water Resources (GOI). 1 April 2002. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Rutherford, Susan (2004). Groundwater Use in Canada. https://www.wcel.org/sites/default/files/publications/Groundwater%20Use%20in%20Canada.pdf.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Côté, Francois (6 February 2006). "Freshwater Management in Canada: IV. Groundwater" (PDF). Library of Parliament.

- "قانون توزیع عادلانه آب - ویکینبشته". fa.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2019-07-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Underground water. |