Golden Gate Bridge

The Golden Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Golden Gate, the one-mile-wide (1.6 km) strait connecting San Francisco Bay and the Pacific Ocean. The structure links the U.S. city of San Francisco, California—the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula—to Marin County, carrying both U.S. Route 101 and California State Route 1 across the strait. The bridge is one of the most internationally recognized symbols of San Francisco and California. It was initially designed by engineer Joseph Strauss in 1917. It has been declared one of the Wonders of the Modern World by the American Society of Civil Engineers.[7]

Golden Gate Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 37°49′11″N 122°28′43″W |

| Carries | 6 lanes of |

| Crosses | Golden Gate |

| Locale | San Francisco, California and Marin County, California, U.S. |

| Official name | Golden Gate Bridge |

| Maintained by | Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension, Art Deco, truss arch & truss causeways |

| Material | Steel |

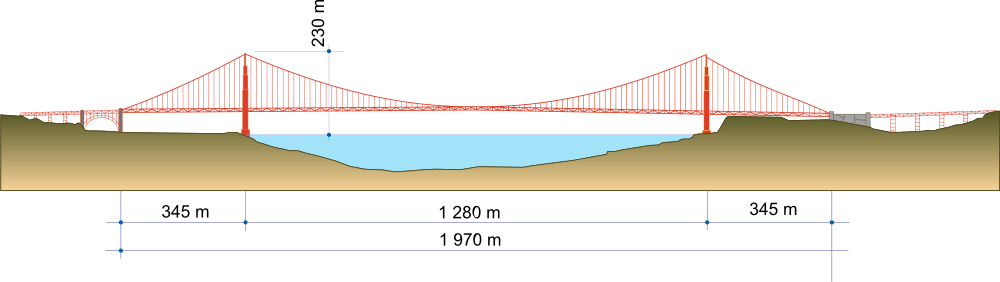

| Total length | 8,980 ft (2,737.1 m),[2] about 1.7 mi (2.7 km) |

| Width | 90 ft (27.4 m) |

| Height | 746 ft (227.4 m) |

| Longest span | 4,200 ft (1,280.2 m),[3] about 0.79 miles (1.28 km) |

| Clearance above | 14 ft (4.3 m) at toll gates, trucks cannot pass |

| Clearance below | 220 ft (67.1 m) at high tide |

| History | |

| Designer | Joseph Strauss, Charles Ellis, Leon Solomon Moisseiff, Irving Morrow |

| Construction start | January 5, 1933 |

| Construction end | April 19, 1937 |

| Opened | May 27, 1937 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 110,000[4] |

| Toll | Cars (southbound only) $8.35 (Pay by plate), $7.35 (FasTrak), $5.35 (carpools during peak hours, FasTrak only) |

| Designated | June 18, 1987[5] |

| Reference no. | 974 |

| Designated | May 21, 1999[6] |

| Reference no. | 222 |

Golden Gate Bridge within the San Francisco Bay Area (westernmost bridge) | |

The Frommer's travel guide describes the Golden Gate Bridge as "possibly the most beautiful, certainly the most photographed, bridge in the world."[8][9] At the time of its opening in 1937, it was both the longest and the tallest suspension bridge in the world, with a main span of 4,200 feet (1,280 m) and a total height of 746 feet (227 m).[10]

History

Ferry service

Before the bridge was built, the only practical short route between San Francisco and what is now Marin County was by boat across a section of San Francisco Bay. A ferry service began as early as 1820, with a regularly scheduled service beginning in the 1840s for the purpose of transporting water to San Francisco.[11]

The Sausalito Land and Ferry Company service, launched in 1867, eventually became the Golden Gate Ferry Company, a Southern Pacific Railroad subsidiary, the largest ferry operation in the world by the late 1920s.[11][12] Once for railroad passengers and customers only, Southern Pacific's automobile ferries became very profitable and important to the regional economy.[13] The ferry crossing between the Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco and Sausalito Ferry Terminal in Marin County took approximately 20 minutes and cost $1.00 per vehicle, a price later reduced to compete with the new bridge.[14] The trip from the San Francisco Ferry Building took 27 minutes.

Many wanted to build a bridge to connect San Francisco to Marin County. San Francisco was the largest American city still served primarily by ferry boats. Because it did not have a permanent link with communities around the bay, the city's growth rate was below the national average.[15] Many experts said that a bridge could not be built across the 6,700-foot (2,000-metre) strait, which had strong, swirling tides and currents, with water 372 ft (113 m) deep[16] at the center of the channel, and frequent strong winds. Experts said that ferocious winds and blinding fogs would prevent construction and operation.[15]

Conception

Although the idea of a bridge spanning the Golden Gate was not new, the proposal that eventually took hold was made in a 1916 San Francisco Bulletin article by former engineering student James Wilkins.[17] San Francisco's City Engineer estimated the cost at $100 million (equivalent to $2.3 billion today), and impractical for the time. He asked bridge engineers whether it could be built for less.[11] One who responded, Joseph Strauss, was an ambitious engineer and poet who had, for his graduate thesis, designed a 55-mile-long (89 km) railroad bridge across the Bering Strait.[18] At the time, Strauss had completed some 400 drawbridges—most of which were inland—and nothing on the scale of the new project.[3] Strauss's initial drawings[17] were for a massive cantilever on each side of the strait, connected by a central suspension segment, which Strauss promised could be built for $17 million (equivalent to $399 million today).[11]

Local authorities agreed to proceed only on the assurance that Strauss would alter the design and accept input from several consulting project experts. A suspension-bridge design was considered the most practical, because of recent advances in metallurgy.[11]

Strauss spent more than a decade drumming up support in Northern California.[19] The bridge faced opposition, including litigation, from many sources. The Department of War was concerned that the bridge would interfere with ship traffic. The US Navy feared that a ship collision or sabotage to the bridge could block the entrance to one of its main harbors. Unions demanded guarantees that local workers would be favored for construction jobs. Southern Pacific Railroad, one of the most powerful business interests in California, opposed the bridge as competition to its ferry fleet and filed a lawsuit against the project, leading to a mass boycott of the ferry service.[11]

In May 1924, Colonel Herbert Deakyne held the second hearing on the Bridge on behalf of the Secretary of War in a request to use federal land for construction. Deakyne, on behalf of the Secretary of War, approved the transfer of land needed for the bridge structure and leading roads to the "Bridging the Golden Gate Association" and both San Francisco County and Marin County, pending further bridge plans by Strauss.[20] Another ally was the fledgling automobile industry, which supported the development of roads and bridges to increase demand for automobiles.[14]

The bridge's name was first used when the project was initially discussed in 1917 by M.M. O'Shaughnessy, city engineer of San Francisco, and Strauss. The name became official with the passage of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District Act by the state legislature in 1923, creating a special district to design, build and finance the bridge.[21] San Francisco and most of the counties along the North Coast of California joined the Golden Gate Bridge District, with the exception being Humboldt County, whose residents opposed the bridge's construction and the traffic it would generate.[22]

Design

Strauss was chief engineer in charge of overall design and construction of the bridge project.[15] However, because he had little understanding or experience with cable-suspension designs,[23] responsibility for much of the engineering and architecture fell on other experts. Strauss's initial design proposal (two double cantilever spans linked by a central suspension segment) was unacceptable from a visual standpoint. The final graceful suspension design was conceived and championed by Leon Moisseiff, the engineer of the Manhattan Bridge in New York City.[24]

Irving Morrow, a relatively unknown residential architect, designed the overall shape of the bridge towers, the lighting scheme, and Art Deco elements, such as the tower decorations, streetlights, railing, and walkways. The famous International Orange color was Morrow's personal selection, winning out over other possibilities, including the US Navy's suggestion that it be painted with black and yellow stripes to ensure visibility by passing ships.[15][25]

Senior engineer Charles Alton Ellis, collaborating remotely with Moisseiff, was the principal engineer of the project.[26] Moisseiff produced the basic structural design, introducing his "deflection theory" by which a thin, flexible roadway would flex in the wind, greatly reducing stress by transmitting forces via suspension cables to the bridge towers.[26] Although the Golden Gate Bridge design has proved sound, a later Moisseiff design, the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge, collapsed in a strong windstorm soon after it was completed, because of an unexpected aeroelastic flutter.[27] Ellis was also tasked with designing a "bridge within a bridge" in the southern abutment, to avoid the need to demolish Fort Point, a pre–Civil War masonry fortification viewed, even then, as worthy of historic preservation. He penned a graceful steel arch spanning the fort and carrying the roadway to the bridge's southern anchorage.[28]

Ellis was a Greek scholar and mathematician who at one time was a University of Illinois professor of engineering despite having no engineering degree. He eventually earned a degree in civil engineering from the University of Illinois prior to designing the Golden Gate Bridge and spent the last twelve years of his career as a professor at Purdue University. He became an expert in structural design, writing the standard textbook of the time.[29] Ellis did much of the technical and theoretical work that built the bridge, but he received none of the credit in his lifetime. In November 1931, Strauss fired Ellis and replaced him with a former subordinate, Clifford Paine, ostensibly for wasting too much money sending telegrams back and forth to Moisseiff.[29] Ellis, obsessed with the project and unable to find work elsewhere during the Depression, continued working 70 hours per week on an unpaid basis, eventually turning in ten volumes of hand calculations.[29]

With an eye toward self-promotion and posterity, Strauss downplayed the contributions of his collaborators who, despite receiving little recognition or compensation,[23] are largely responsible for the final form of the bridge. He succeeded in having himself credited as the person most responsible for the design and vision of the bridge.[29] Only much later were the contributions of the others on the design team properly appreciated.[29] In May 2007, the Golden Gate Bridge District issued a formal report on 70 years of stewardship of the famous bridge and decided to give Ellis major credit for the design of the bridge.

Finance

The Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District, authorized by an act of the California Legislature, was incorporated in 1928 as the official entity to design, construct, and finance the Golden Gate Bridge.[15] However, after the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the District was unable to raise the construction funds, so it lobbied for a $30 million bond measure (equivalent to $447 million today). The bonds were approved in November 1930,[18] by votes in the counties affected by the bridge.[30] The construction budget at the time of approval was $27 million ($413 million today). However, the District was unable to sell the bonds until 1932, when Amadeo Giannini, the founder of San Francisco–based Bank of America, agreed on behalf of his bank to buy the entire issue in order to help the local economy.[11]

Construction

Construction began on January 5, 1933.[11] The project cost more than $35 million[31] ($514 million in 2018 dollars[32]), and was completed ahead of schedule and $1.3 million under budget (equivalent to $24.2 million today).[33] The Golden Gate Bridge construction project was carried out by the McClintic-Marshall Construction Co., a subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel Corporation founded by Howard H. McClintic and Charles D. Marshall, both of Lehigh University.

Strauss remained head of the project, overseeing day-to-day construction and making some groundbreaking contributions. A graduate of the University of Cincinnati, he placed a brick from his alma mater's demolished McMicken Hall in the south anchorage before the concrete was poured. He innovated the use of movable safety netting beneath the construction site, which saved the lives of many otherwise-unprotected ironworkers. Of eleven men killed from falls during construction, ten were killed on February 17, 1937, when the bridge was near completion and the net failed under the stress of a scaffold that had fallen.[34] The workers' platform that was attached to a rolling hanger on a track collapsed when the bolts that were connected to the track were too small and the amount of weight was too great to bear. The platform fell into the safety net, but was too heavy and the net gave way. Two out of the twelve workers survived the 200-foot (61 m) fall into the icy waters, including the 37-year-old foreman, Slim Lambert. Nineteen others who were saved by the net over the course of construction became members of the Half Way to Hell Club.[35]

The project was finished and opened May 27, 1937. The Bridge Round House diner was then included in the southeastern end of the Golden Gate Bridge, adjacent to the tourist plaza which was renovated in 2012.[36] The Bridge Round House, an Art Deco design by Alfred Finnila completed in 1938, has been popular throughout the years as a starting point for various commercial tours of the bridge and an unofficial gift shop.[37] The diner was renovated in 2012[36] and the gift shop was then removed as a new, official gift shop has been included in the adjacent plaza.[37]

During the bridge work, the Assistant Civil Engineer of California Alfred Finnila had overseen the entire iron work of the bridge as well as half of the bridge's road work.[38] With the death of Jack Balestreri in April 2012, all workers involved in the original construction are now deceased.

Torsional bracing retrofit

On December 1, 1951, a windstorm revealed swaying and rolling instabilities of the bridge, resulting in its closure.[39] In 1953 and 1954, the bridge was retrofitted with lateral and diagonal bracing that connected the lower chords of the two side trusses. This bracing stiffened the bridge deck in torsion so that it would better resist the types of twisting that had destroyed the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in 1940.[40]

Bridge Deck Replacement (1982-1986)

The original bridge used a concrete deck. Salt carried by fog or mist reached the rebar, causing corrosion and concrete spalling. From 1982 to 1986, the original bridge deck, in 747 sections, was systematically replaced with a 40% lighter, and stronger, steel orthotropic deck panels, over 401 nights without closing the roadway completely to traffic. The roadway was also widened by two feet, resulting in outside curb lane width of 11 feet, instead of 10 feet for the inside lanes. This deck replacement was the bridge's greatest engineering project since it was built and cost over $68 million.[41]

Opening festivities, and 50th and 75th anniversaries

The bridge-opening celebration began on May 27, 1937, and lasted for one week. The day before vehicle traffic was allowed, 200,000 people crossed either on foot or on roller skates.[11] On opening day, Mayor Angelo Rossi and other officials rode the ferry to Marin, then crossed the bridge in a motorcade past three ceremonial "barriers," the last a blockade of beauty queens who required Joseph Strauss to present the bridge to the Highway District before allowing him to pass. An official song, "There's a Silver Moon on the Golden Gate," was chosen to commemorate the event. Strauss wrote a poem that is now on the Golden Gate Bridge entitled "The Mighty Task is Done." The next day, President Franklin D. Roosevelt pushed a button in Washington, D.C. signaling the official start of vehicle traffic over the Bridge at noon. As the celebration got out of hand there was a small riot in the uptown Polk Gulch area. Weeks of civil and cultural activities called "the Fiesta" followed. A statue of Strauss was moved in 1955 to a site near the bridge.[17]

In May 1987, as part of the 50th anniversary celebration, the Golden Gate Bridge district again closed the bridge to automobile traffic and allowed pedestrians to cross the bridge. However, this celebration attracted 750,000 to 1,000,000 people, and ineffective crowd control meant the bridge became congested with roughly 300,000 people, causing the center span of the bridge to flatten out under the weight.[42] Although the bridge is designed to flex in that way under heavy loads, and was estimated not to have exceeded 40% of the yielding stress of the suspension cables,[43] bridge officials stated that uncontrolled pedestrian access was not being considered as part of the 75th anniversary on Sunday, May 27, 2012,[44][45][46] because of the additional law enforcement costs required "since 9/11."[47]

A pedestrian poses at the old railing on opening day, 1937.

A pedestrian poses at the old railing on opening day, 1937. Official invitation to the opening of the bridge. This copy was sent to the City of Seattle.

Official invitation to the opening of the bridge. This copy was sent to the City of Seattle.

Structural specifications

Until 1964, the Golden Gate Bridge had the longest suspension bridge main span in the world, at 4,200 feet (1,300 m). Since 1964 its main span length has been surpassed by fifteen bridges; it now has the second-longest main span in the Americas, after the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge in New York City. The total length of the Golden Gate Bridge from abutment to abutment is 8,981 feet (2,737 m).[48]

The Golden Gate Bridge's clearance above high water averages 220 feet (67 m) while its towers, at 746 feet (227 m) above the water,[48] were the world's tallest on a suspension bridge until 1993 when it was surpassed by the Mezcala Bridge, in Mexico.

The weight of the roadway is hung from 250 pairs of vertical suspender ropes, which are attached to two main cables. The main cables pass over the two main towers and are fixed in concrete at each end. Each cable is made of 27,572 strands of wire. The total length of galvanized steel wire used to fabricate both main cables is estimated to be 80,000 miles (130,000 km).[48] Each of the bridge's two towers has approximately 600,000 rivets.[49]

In the 1960s, when the Bay Area Rapid Transit system (BART) was being planned, the engineering community had conflicting opinions about the feasibility of running train tracks north to Marin County over the bridge.[50] In June 1961, consultants hired by BART completed a study that determined the bridge's suspension section was capable of supporting service on a new lower deck.[51] In July 1961, one of the bridge's consulting engineers, Clifford Paine, disagreed with their conclusion.[52] In January 1962, due to more conflicting reports on feasibility, the bridge's board of directors appointed an engineering review board to analyze all the reports. The review board's report, released in April 1962, concluded that running BART on the bridge was not advisable.[53]

Aesthetics

Aesthetics was the foremost reason why the first design of Joseph Strauss was rejected. Upon re-submission of his bridge construction plan, he added details, such as lighting, to outline the bridge's cables and towers.[54] In 1999, it was ranked fifth on the List of America's Favorite Architecture by the American Institute of Architects.

The color of the bridge is officially an orange vermilion called international orange.[55] The color was selected by consulting architect Irving Morrow[56] because it complements the natural surroundings and enhances the bridge's visibility in fog.[57]

The bridge was originally painted with red lead primer and a lead-based topcoat, which was touched up as required. In the mid-1960s, a program was started to improve corrosion protection by stripping the original paint and repainting the bridge with zinc silicate primer and vinyl topcoats.[58][55] Since 1990, acrylic topcoats have been used instead for air-quality reasons. The program was completed in 1995 and it is now maintained by 38 painters who touch up the paintwork where it becomes seriously corroded.[59] The ongoing maintenance task of painting the bridge is continuous.[60]

.jpg) A view of the Golden Gate Bridge from the Marin Headlands on a foggy morning at sunrise

A view of the Golden Gate Bridge from the Marin Headlands on a foggy morning at sunrise View of Marin from the south tower

View of Marin from the south tower Top of the south tower

Top of the south tower

Traffic

Most maps and signage mark the bridge as part of the concurrency between U.S. Route 101 and California State Route 1. Although part of the National Highway System, the bridge is not officially part of California's Highway System.[61] For example, under the California Streets and Highways Code § 401, Route 101 ends at "the approach to the Golden Gate Bridge" and then resumes at "a point in Marin County opposite San Francisco". The Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District has jurisdiction over the segment of highway that crosses the bridge instead of the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans).

The movable median barrier between the lanes is moved several times daily to conform to traffic patterns. On weekday mornings, traffic flows mostly southbound into the city, so four of the six lanes run southbound. Conversely, on weekday afternoons, four lanes run northbound. During off-peak periods and weekends, traffic is split with three lanes in each direction.[62]

From 1968 to 2015, opposing traffic was separated by small, plastic pylons; during that time, there were 16 fatalities resulting from 128 head-on collisions.[63] To improve safety, the speed limit on the Golden Gate Bridge was reduced from 50 to 45 mph (80 to 72 km/h) on October 1, 1983.[64] Although there had been discussion concerning the installation of a movable barrier since the 1980s, only in March 2005 did the Bridge Board of Directors commit to finding funding to complete the $2 million study required prior to the installation of a movable median barrier.[63] Installation of the resulting barrier was completed on January 11, 2015, following a closure of 45.5 hours to private vehicle traffic, the longest in the bridge's history. The new barrier system, including the zipper trucks, cost approximately $30.3 million to purchase and install.[63][65]

Usage and tourism

The bridge is popular with pedestrians and bicyclists, and was built with walkways on either side of the six vehicle traffic lanes. Initially, they were separated from the traffic lanes by only a metal curb, but railings between the walkways and the traffic lanes were added in 2003, primarily as a measure to prevent bicyclists from falling into the roadway.[66]

The bridge carries about 112,000 vehicles per day according to the Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District.[67]

The main walkway is on the eastern side, and is open for use by both pedestrians and bicycles in the morning to mid-afternoon during weekdays (5:00 a.m. to 3:30 p.m.), and to pedestrians only for the remaining daylight hours (until 6:00 p.m., or 9:00 p.m. during DST). The eastern walkway is reserved for pedestrians on weekends (5:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., or 9:00 p.m. during DST), and is open exclusively to bicyclists in the evening and overnight, when it is closed to pedestrians. The western walkway is open only for bicyclists and only during the hours when they are not allowed on the eastern walkway.[68]

Bus service across the bridge is provided by two public transportation agencies: San Francisco Muni and Golden Gate Transit. Muni offers Saturday and Sunday service on the Marin Headlands Express bus line, and Golden Gate Transit runs numerous bus lines throughout the week.[69][70] The southern end of the bridge, near the toll plaza and parking lot, is also accessible daily from 5:30 a.m. to midnight by Muni line 28.[71] The Marin Airporter, a private company, also offers service across the bridge between Marin County and San Francisco International Airport.[72]

A visitor center and gift shop, originally called the "Bridge Pavilion" (since renamed the “Golden Gate Bridge Welcome Center”), is located on the San Francisco side of the bridge, adjacent to the southeast parking lot. It opened in 2012, in time for the bridge's 75th anniversary celebration. A cafe, outdoor exhibits, and restroom facilities are located nearby.[73] On the Marin side of the bridge, only accessible from the northbound lanes, is the H. Dana Bower Rest Area and Vista Point,[74] named after the first landscape architect for the California Division of Highways.[75]

Lands and waters under and around the bridge are homes to varieties of wildlife such as bobcats and sea lions.[76][77] Three species of cetaceans (whales) that had been absent in the area for many years have shown recent recoveries/(re)colonizations in the vicinity of the bridge; researchers studying them have encouraged stronger protections and recommended that the public watch them from the bridge or from land, or use a local whale watching operator.[78][79][80]

Tolls

When the Golden Gate Bridge opened in 1937, the toll was 50 cents per car (equivalent to $8.89 in 2019), collected in each direction. In 1950 it was reduced to 40 cents each way ($4.25 in 2019), then lowered to 25 cents in 1955 ($2.39 in 2019). In 1968, the bridge was converted to only collect tolls from southbound traffic, with the toll amount reset back to 50 cents ($3.68 in 2019).[81]

The last of the construction bonds were retired in 1971, with $35 million (equivalent to $221M in 2019) in principal and nearly $39 million ($246M in 2019) in interest raised entirely from bridge tolls.[64] Tolls continued to be collected and subsequently incrementally raised; by 1991, the toll was $3.00 (equivalent to $5.63 in 2019).[81]

The bridge began accepting tolls via the FasTrak electronic toll collection system in 2002, with $4 tolls for FasTrak users and $5 for those paying cash (equivalent to $5.69 and $7.11 respectively in 2019).[81] In November 2006, the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District recommended a corporate sponsorship program for the bridge to address its operating deficit, projected at $80 million over five years. The District promised that the proposal, which it called a "partnership program", would not include changing the name of the bridge or placing advertising on the bridge itself. In October 2007, the Board unanimously voted to discontinue the proposal and seek additional revenue through other means, most likely a toll increase.[82][83] The District later increased the toll amounts in 2008 to $5 for FasTrak users and $6 to those paying cash (equivalent to $5.94 and $7.12 respectively in 2019).[81]

In an effort to save $19.2 million over the following 10 years, the Golden Gate District voted in January 2011 to eliminate all toll takers by 2012 and use only open road tolling.[84] Subsequently, this was delayed and toll taker elimination occurred in March 2013. The cost savings have been revised to $19 million over an eight-year period. In addition to FasTrak, the Golden Gate District implemented the use of license plate tolling (branded as "Pay-by-Plate"), and also a one time payment system for drivers to pay before or after their trip on the bridge. Twenty-eight positions were eliminated as part of this plan.[85]

On April 7, 2014, the toll for users of FasTrak was increased from $5 to $6 (equivalent to $6.48 in 2019), while the toll for drivers using either the license plate tolling or the one time payment system was raised from $6 to $7 (equivalent to $7.56 in 2019). Bicycle, pedestrian, and northbound motor vehicle traffic remain toll free. For vehicles with more than two axles, the toll rate was $7 per axle for those using license plate tolling or the one time payment system, and $6 per axle for FasTrak users. During peak traffic hours, carpool vehicles carrying two or more people and motorcycles paid a discounted toll of $4 (equivalent to $4.32 in 2019); drivers must have had Fastrak to take advantage of this carpool rate.[85] The Golden Gate Transportation District then planned to increase the tolls by 25 cents in July 2015, and then by another 25 cents each of the next three years.[86]

| Effective date | FasTrak | Toll-by-plate | Carpool | Multi-axle vehicle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 7, 2014 | $6.00 | $7.00 | $4.00 | $7.00 per axle |

| July 1, 2015 | $6.25 | $7.25 | $4.25 | $7.25 per axle |

| July 1, 2016 | $6.50 | $7.50 | $4.50 | $7.50 per axle |

| July 1, 2017 | $6.75 | $7.75 | $4.75 | $7.75 per axle |

| July 1, 2018 | $7.00 | $8.00 | $5.00 | $8.00 per axle |

| July 1, 2019 | $7.35 | $8.35 | $5.35 | $8.35 per axle |

Congestion pricing

In March 2008, the Golden Gate Bridge District board approved a resolution to start congestion pricing at the Golden Gate Bridge, charging higher tolls during the peak hours, but rising and falling depending on traffic levels. This decision allowed the Bay Area to meet the federal requirement to receive $158 million in federal transportation funds from USDOT Urban Partnership grant.[88] As a condition of the grant, the congestion toll was to be in place by September 2009.[89][90]

The first results of the study, called the Mobility, Access and Pricing Study (MAPS), showed that a congestion pricing program is feasible.[91] The different pricing scenarios considered were presented in public meetings in December 2008.[92]

In August 2008, transportation officials ended the congestion pricing program in favor of varying rates for metered parking along the route to the bridge including on Lombard Street and Van Ness Avenue.[93]

Issues

Suicides

The Golden Gate Bridge is the second-most used suicide site/suicide bridge in the world, after the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge.[94] The deck is about 245 feet (75 m) above the water.[95] After a fall of four seconds, jumpers hit the water at around 75 mph (120 km/h; 30 m/s). Most die from impact trauma. About 5% survive the initial impact but generally drown or die of hypothermia in the cold water.[96][97]

After years of debate and an estimated more than 1,500 deaths, suicide barriers, consisting of a stainless steel net extending 20 feet from the bridge and supported by structural steel 20 feet under the walkway, began to be installed in April 2017.[98] Construction was first estimated to take approximately four years at a cost of over $200 million.[99] In December 2019, it was reported that construction of the suicide prevention net had fallen two years behind schedule because the lead contractor, Shimmick Construction Co., had been sold in 2017, leading to the slowdown of several existing projects. As of December 2019, the completion date for the Golden Gate Bridge net was set for 2023.[100][101]

Wind

The Golden Gate Bridge was designed to safely withstand winds of up to 68 mph (109 km/h).[102] Until 2008, the bridge was closed because of weather conditions only three times: on December 1, 1951, because of gusts of 69 mph (111 km/h); on December 23, 1982, because of winds of 70 mph (113 km/h); and on December 3, 1983, because of wind gusts of 75 mph (121 km/h).[58] An anemometer placed midway between the two towers on the west side of the bridge, has been used to measure wind speeds. Another anemometer was placed on one of the towers.

As part of the retrofitting of the bridge and installation of the suicide barrier, starting in 2019 the railings on the west side of the pedestrian walkway were replaced with thinner, more flexible slats in order to improve the bridge's aerodynamic tolerance of high wind to 100 mph (161 km/h). Starting in June 2020, reports were received of a loud hum, heard across San Francisco and Marin County, produced by the new railing slats when a strong west wind was blowing.[103] The sound had been predicted from wind tunnel tests,[102] but not included in the environmental impact report; ways of ameliorating it are being considered.[104]

Seismic vulnerability and improvements

Modern knowledge of the effect of earthquakes on structures led to a program to retrofit the Golden Gate to better resist seismic events. The proximity of the bridge to the San Andreas Fault places it at risk for a significant earthquake. Once thought to have been able to withstand any magnitude of foreseeable earthquake, the bridge was actually vulnerable to complete structural failure (i.e., collapse) triggered by the failure of supports on the 320-foot (98 m) arch over Fort Point.[105] A $392 million program was initiated to improve the structure's ability to withstand such an event with only minimal (repairable) damage. A custom-built electro-hydraulic synchronous lift system for construction of temporary support towers and a series of intricate lifts, transferring the loads from the existing bridge onto the temporary supports, were completed with engineers from Balfour Beatty and Enerpac, without disrupting day-to-day commuter traffic.[106][107] Although the retrofit was initially planned to be completed in 2012, as of May 2017 it was expected to take several more years.[107][108][109]

The former elevated approach to the Golden Gate Bridge through the San Francisco Presidio, known as Doyle Drive, dated to 1933 and was named after Frank P. Doyle. Doyle, the president of the Exchange Bank in Santa Rosa and son of the bank's founder, was the man who, more than any other person, made it possible to build the Golden Gate Bridge.[110] The highway carried about 91,000 vehicles each weekday between downtown San Francisco and the North Bay and points north.[111] The road was deemed "vulnerable to earthquake damage", had a problematic 4-lane design, and lacked shoulders; a San Francisco County Transportation Authority study recommended that it be replaced. Construction on the $1 billion replacement,[112] temporarily known as the Presidio Parkway, began in December 2009.[113] The elevated Doyle Drive was demolished on the weekend of April 27–30, 2012, and traffic used a part of the partially completed Presidio Parkway, until it was switched onto the finished Presidio Parkway on the weekend of July 9–12, 2015. As of May 2012, an official at Caltrans said there is no plan to permanently rename the portion known as Doyle Drive.[114]

Gallery

See also

- 25 de Abril Bridge, a bridge with a similar design in Portugal

- The Bridge, a 2006 documentary on suicides from the Bridge

- Golden Gate Bridge in popular culture

- List of Historic Civil Engineering Landmarks

- List of longest suspension bridge spans

- List of San Francisco Designated Landmarks

- List of tallest bridges

- San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge

- Suicide bridge

- Suspension bridge

References

- "About Us". goldengate.org. Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- Golden Gate Bridge at Structurae

- Denton, Harry et al. (2004) "Lonely Planet San Francisco" Lonely Planet, United States, ISBN 1-74104-154-6

- "Annual Vehicle Crossings and Toll Revenues, FY 1938 to FY 2011". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- "Golden Gate Bridge". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- "American Society of Civil Engineers Seven Wonders". Asce.org. July 19, 2010. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Levine, Dan (1993). Frommer's comprehensive travel guide, California '93. New York: Prentice Hall Travel. p. 118. ISBN 0671846744.

- McGrath, Nancy (1985). Frommer's 1985-86 guide to San Francisco. New York: Frommer/Pasmantier Pub. p. 10. ISBN 0671526545.

- History.com Editors (2019). Golden Gate Bridge. History. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "Two Bay Area Bridges". US Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- Fimrite, Peter (April 28, 2005). "Ferry tale – the dream dies hard: 2 historic boats that plied the bay seek buyer – anybody". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- Harlan, George H. (1967). San Francisco Bay Ferryboats. Howell-North Books.

- Span, Guy (May 4, 2002). "So Where Are They Now? The Story of San Francisco's Steel Electric Empire". Bay Crossings. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- Sigmund, Pete (2006). "The Golden Gate: 'The Bridge That Couldn't Be Built'". Construction Equipment Guide. Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- Barnard, Hanes, Rubin, Kvitek (July 18, 2006). "Giant Sand Waves at the Mouth of San Francisco Bay" (PDF). Eos. 87 (29): 285. doi:10.1029/2006EO290003. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 18, 2018. Retrieved April 22, 2012.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Owens, T.O. (2001). The Golden Gate Bridge. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8239-5016-6.

- "The American Experience:People & Events: Joseph Strauss (1870–1938)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- "Bridging the Bay: Bridges That Never Were". UC Berkeley Library. 1999. Archived from the original on July 18, 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

- Miller, John B. (2002) "Case Studies in Infrastructure Delivery" Springer, ISBN 0-7923-7652-8.

- Gudde, Erwin G. (1949). California Place Names. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 130. OCLC 37647557.

- "Special District Formed – Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District". Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- "People and Events: Joseph Strauss (1870–1938)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- "Golden Gate Bridge Design". goldengatebridge.org. Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- "Irving Morrow | American Experience | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved October 5, 2019.

- "American Experience:Leon Moisseiff (1872–1943)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- Billah, K.; Scanlan, R. (1991). "Resonance, Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. Undergraduate Physics Textbooks. 59 (2): 118–124. doi:10.1119/1.16590.

- "The Point of Fort Point: A Brief History". Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- "The American Experience:Charles Alton Ellis (1876–1949)". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- Jackson, Donald C. (1995) "Great American Bridges and Dams" John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 0-471-14385-5

- "Bridging the Bay: Bridges That Never Were". UC Berkeley Library. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2019). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved April 6, 2019. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- "72 years ago today, iconic Golden Gate Bridge finished construction ahead of schedule & $1.3 million under budget". May 27, 2009. Retrieved April 10, 2013.

- "Life On The American Newsfront: Ten Men Fall To Death From Golden Gate Bridge". Life: 20–21. March 1, 1937.

- "Frequently Asked Questions about the Golden Gate Bridge". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- King, John (May 25, 2012). "Golden Gate Bridge's Plaza Flawed but Workable". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Kligman, David (May 25, 2012). "From Sea to Shining Sea: PG&E's Earley Joins Tribute to Golden Gate Bridge". Currents. PG&E.

- San Francisco Examiner. May 27, 1982. No. 147, p. 2. Golden Gate Bridge – 45th anniversary of completion.

- Van Niekerken, Bill (June 13, 2016). "When the Golden Gate Bridge was closed by a violent storm". Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- "Resisting the Twisting". Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- "Bridge Deck Replacement (1982-1986)". goldengate.org. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- Tung, Stephen (May 23, 2012). "The Day the Golden Gate Bridge Flattened". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Pollalis, Spiro N.; Otto, Caroline (1990). "THE GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE" (PDF). Harvard Design School. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- McCarthy, Terrence (May 26, 1987). "Golden Gate Crowd Made Bridge Bend". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- Prado, Mark (July 23, 2010). "Golden Gate Bridge officials nix walk for 75th anniversary". Marin Independent Journal. Archived from the original on December 27, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- "Golden Gate Festival :: Golden Gate Bridge 75th Anniversary". Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- Fowler, Geoffrey A. (May 24, 2012). "A Historian's Long View of Golden Gate Bridge". The Wall Street Journal. pp. A13C. Retrieved August 31, 2013.

- "Bridge Design and Construction Statistics". goldengatebridge.org. Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- "Frequently Asked Questions about the Golden Gate Bridge: How many rivets are in each tower of the Golden Gate Bridge?". goldengatebridge.org. Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "A History of BART". Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Rapid Transit for the San Francisco Bay Area" (PDF). LA Metro Library. Parsons Brinkerhoff / Tudor / Bechtel. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Prado, Mark (August 7, 2010). "Did Marin lose out on BART?". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- Ammann, Othmar H.; Masters, Frank M.; Newmark, Nathan M. (April 1962). Report on Proposed Installation of Rapid Transit Trains on Golden Gate Bridge (Report). Golden Gate Bridge And Highway District. p. 8.

- Rodriguez, Joseph A.; Urban Rivalry in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1930s (2000). "Planning". Journal of Planning Education and Research. 20: 66–76. doi:10.1177/073945600128992609.

- "Golden Gate Bridge: Construction Data". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- Stamberg, Susan. "The Golden Gate Bridge's Accidental Color". NPR. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 94. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- "Frequently Asked Questions about the Golden Gate Bridge". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- "Golden Gate Bridge: Construction Data: How Many Ironworkers and Painters Maintain the Golden Gate Bridge?". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. 2006. Retrieved April 13, 2006.

- Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District (2018). "Painting the Bridge". goldengatebridge.org. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

The Bridge is painted continuously. Painting the Bridge is an ongoing task and a primary maintenance job.

- "Toll Rates & Traffic Operations". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "Roadway Configuration / Reversible Lanes". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- "Additional Information – Movable Median Barrier Project". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- "Key Dates". Research Library. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- Asimov, Nanette (January 11, 2015). "Golden Gate Bridge work finished early as barrier is installed". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- Lucas, Scott (July 18, 2013). "Kevin Hines Is Still Alive". Modern Luxury. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "Bridge Operations". Goldengate.org. The Golden Gate Bridge. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- The Golden Gate Bridge, Sidewalk Access for Pedestrians and Bicyclists. Goldengatebridge.org. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Muni Route 76X Marin Headlands". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- "Golden Gate Transit bus service" (PDF). Golden Gate Transit. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- "Muni Route 28 19th Avenue". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- "Marin Airporter, SFO Airport Transportation, Bus Service, Marin County, CA". Marin Airporter.

- "Site Improvements". Golden Gate Bridge 75th Anniversary. Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- "H. Dana Bowers Rest Area". California Department of Transportation. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- 2015 Named Freeways, Highways, Structures and Other Appurtenances in California (PDF). California Department of Transportation. pp. 183, 205. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- Animals – Golden Gate National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved on July 30, 2017

- The SFGate. 2015. Whale, sea lions put on a show near Golden Gate Bridge. Retrieved on July 30, 2017

- GOLDEN GATE CETACEAN RESEARCH. Retrieved on July 30, 2017

- Keener B.. 2017. Ask The Naturalist: Why Are There Humpback Whales In the San Francisco Bay Right Now?. Retrieved on July 30, 2017

- Woodrow M.. 2017. Experts concerned about whale safety in San Francisco Bay. The ABC7. Retrieved on July 30, 2017

- "Traffic/Toll Data". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- Curiel, Jonathan (October 27, 2007). "Golden Gate Bridge directors reject sponsorship proposals". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

- "Partnership Program Status". Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (January 29, 2011). "Golden Gate Bridge to eliminate toll takers". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- "Toll 2014". Goldengate.org. April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (April 7, 2014). "Tolls for crossing Golden Gate Bridge rise $1". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 26, 2014.

- "Summary of Recommendations, February 27, 2014" (PDF). Board of Directors. Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District. pp. 5–6. Retrieved May 24, 2015.

- Bolling, David (May 29, 2008). "GG Bridge tolls could top $7, June 11 meeting will set new rates". Sonoma Index-Tribune.

- The San Francisco Chronicle (March 19, 2008). "Congestion Pricing Approved for Golden Gate Bridge". planetizen.com. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (March 15, 2008). "Bridge raises tolls, denies Doyle Dr. funds". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- "Mobility, Access and Pricing Study". San Francisco County Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- Wollan, Malia (January 4, 2009). "San Francisco Studies Fees to Ease Traffic". The New York Times. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (August 12, 2008). "Golden Gate Bridge congestion toll plan dies". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Bone, James (October 13, 2008). "Golden Gate bridge in San Fransico [sic] gets safety net to deter suicides". The Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017 – via Journalisted.

- "Suspension Bridges" (PDF). snu.ac.kr. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 12, 2003.

- Koopman, John (November 2, 2005). "Lethal Beauty. No easy death: Suicide by bridge is gruesome, and death is almost certain. The fourth in a seven-part series on the Golden Gate Bridge barrier debate". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- Bateson, John (September 29, 2013). "The suicide magnet that is the Golden Gate Bridge". Los Angeles Times (opinion). Retrieved October 14, 2013.

- Houston, Will (February 18, 2019). "Golden Gate Bridge suicide barrier starting to take shape". Ukiah Daily Journal.

- "Suicide Barriers Going Up At Golden Gate Bridge After Over 1.5K Deaths". CBS San Francisco. CBS Broadcasting Inc. April 13, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- "Construction of Suicide Net at Golden Gate Bridge Is 2 Years Behind Schedule". KTLA. December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- "Golden Gate Bridge Suicide Deterrent Net Project Update" (PDF) (press release). Golden Gate Bridge Highway & Transportation District. December 12, 2019.

- Swan, Rachel (June 8, 2020). "Hear that ghostly hum on the Golden Gate Bridge? It's here to stay". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Ting, Eric (June 6, 2020). "Why the Golden Gate Bridge made strange noises with the wind Friday". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Chamings, Andrew (July 1, 2020). "Golden Gate Bridge officials look to fix 'screeching that sounds like torture'". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Nolte, Carl (May 28, 2007). "70 Years: Spanning the Golden Gate: New will blend in with the old as part of bridge earthquake retrofit project". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Showing fancy foot work. Roads&Bridges (December 28, 2000).

- Golden Gate Bridge Authority (May 2008). "Overview of Golden Gate Bridge Seismic Retrofit". Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- Gonchar, Joann (January 3, 2005). "Famed Golden Gate Span Undergoes Complex Seismic Revamp". McGraw-Hill Construction. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- "Costly Golden Gate Bridge Retrofit Still Years Away From Completion". May 24, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- "Presidio Parkway re-envisioning Doyle Drive". Presidio Parkway Project. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- "Doyle Drive Replacement Project". San Francisco County Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on April 26, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- Cabanatuan, Michael (January 5, 2010). "Doyle Drive makeover will affect drivers soon". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- "Current Construction Activity". Presidio Parkway re-envisioning Doyle Drive. Presidio Parkway. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- "Smith: It's wrecked, but it's still 'Doyle Drive'". Press Democrat. May 1, 2012.

Further reading

- Cassady, Stephen (1979). Spanning the Gate (Commemorative edition, 1987 ed.). Squarebooks. ISBN 978-0916290368.

- Dyble, Louise Nelson; the Golden Gate Bridge (2009). Paying the Toll: Local Power, Regional Politics. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812222784.

- Friend, Tad (October 13, 2003). "Jumpers: The fatal grandeur of the Golden Gate Bridge". The New Yorker. 79 (30). p. 48. Archived from the original on November 8, 2006.

- Guthman, Edward; an easy route to death have long made the Golden Gate Bridge a magnet for suicides (October 30, 2005). "Lethal Beauty / The Allure: Beauty". San Francisco Chronicle.

- Schwartz, Harvey (2015). Building the Golden Gate Bridge: A Workers' Oral History. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295995069.

- Starr, Kevin (2010). Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America's Greatest Bridge. Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-534-3.

- "Golden Gate Bridge Natural Frequencies". Vibrationdata.com. April 5, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Official website

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. CA-31, "Golden Gate Bridge", 41 photos, 6 color transparencies, 2 data pages, 4 photo caption pages

- Links for Golden Gate Bridge at Curlie

- "Images of the Golden Gate Bridge". San Francisco Public Library's Historical Photograph database.

- Marshal 'J' (Narrator) (1962). "The Bridge Builders". KPIX-TV. (A documentary film about the construction of the Golden Gate Bridge.)

- "San Francisco To Have World's Greatest Bridge". Popular Science. March 1931.

- "Golden Gate Bridge facts". sftodo.com. (Educational poster.)

- "End of Land Sadness – The history of Suicide and the Golden Gate Bridge". Golden Gate Bridge Movie.