Palace of Fine Arts

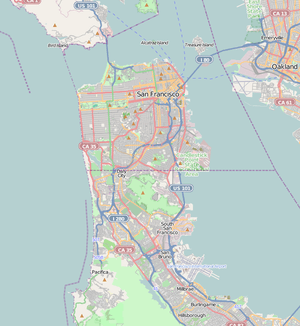

The Palace of Fine Arts in the Marina District of San Francisco, California is a monumental structure originally constructed for the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in order to exhibit works of art. Completely rebuilt from 1964 to 1974,[1] it is one of only a few surviving structures from the Exposition.

Palace of Fine Arts | |

.jpg) The Palace of Fine Arts, 2020 | |

| |

| Location | 3301 Lyon St., San Francisco, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°48′10″N 122°26′54″W |

| Area | 17 acres (6.9 ha) |

| Architect | William Gladstone Merchant; Bernard Maybeck |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 04000659[1] |

| SFDL No. | 88 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 5, 2005 |

| Designated SFDL | 1977[2] |

The most prominent building of the complex, a 162 feet (49 m) high[1] open rotunda, is enclosed by a lagoon on one side, and is neighboring a large, curved exhibition center on the other side, which is separated from the lagoon by colonnades. As of 2019, the exhibition center (one of San Francisco's largest single-story buildings) was being used as a venue for events such as weddings or trade fairs.[3]

Conceived to evoke a decaying ruin of ancient Rome,[1] the Palace of Fine Arts became one of San Francisco's most recognizable landmarks.[4] A renovation of the lagoon, walkways, and a seismic retrofit were completed in early 2009.

History

The Palace of Fine Arts was one of ten palaces at the heart of the Panama-Pacific Exhibition, which also included the exhibit palaces of Education, Liberal Arts, Manufactures, Varied Industries, Agriculture, Food Products, Transportation, Mines and Metallurgy and the Palace of Machinery.[5] The Palace of Fine Arts was designed by Bernard Maybeck, who took his inspiration from Roman and Ancient Greek architecture[6] in designing what was essentially a fictional ruin from another time.

While most of the exposition was demolished when the exposition ended, the Palace was so beloved that a Palace Preservation League, founded by Phoebe Apperson Hearst, was founded while the fair was still in progress.[7]

For a time the Palace housed a continuous art exhibit, and during the Great Depression, W.P.A. artists were commissioned to replace the decayed Robert Reid murals on the ceiling of the rotunda. From 1934 to 1942 the exhibition hall was home to eighteen lighted tennis courts. During World War II, it was requisitioned by the military for storage of trucks and jeeps. At the end of the war, when the United Nations was created in San Francisco, limousines used by the world's statesmen came from a motor pool there. From 1947 on the hall was put to various uses: as a city Park Department warehouse; as a telephone book distribution center; as a flag and tent storage depot; and even as temporary Fire Department headquarters.[8]

While the Palace had been saved from demolition, its structure was not stable. Originally intended to only stand for the duration of the Exhibition, the colonnade and rotunda were not built of durable materials, and thus framed in wood and then covered with staff, a mixture of plaster and burlap-type fiber. As a result of the construction and vandalism, by the 1950s the simulated ruin was in fact a crumbling ruin.[9]

In 1964, the original Palace was completely demolished, with only the steel structure of the exhibit hall left standing. The buildings were then reconstructed until 1974[1] in permanent, light-weight, poured-in-place concrete, and steel I-beams were hoisted into place for the dome of the rotunda. All the decorations and sculpture were constructed anew. The only changes were the absence of the murals in the dome, two end pylons of the colonnade, and the original ornamentation of the exhibit hall.

In 1969, the former Exhibit Hall became home to the Exploratorium interactive museum, and, in 1970, also became the home of the 966-seat Palace of Fine Arts Theater.[10] In 2003, the City of San Francisco along with the Maybeck Foundation created a public-private partnership to restore the Palace and by 2010 work was done to restore and seismically retrofit the dome, rotunda, colonnades and lagoon. In January 2013, the Exploratorium closed in preparation for its permanent move to the Embarcadero.

In April 2020, during the coronavirus pandemic, plans were announced to convert the Palace of Fine Arts into a temporary shelter for 162 homeless people.[4] The decision was reversed shortly afterwards, following protests by residents of the neighboring wealthy Marina neighborhood and concerns that the lodging conditions would be inadequate.[11]

Today, Australian eucalyptus trees fringe the eastern shore of the lagoon. Many forms of wildlife have made their home there including swans, ducks (particularly migrating fowl), geese, turtles, frogs, and raccoons.

Design

Built around a small artificial lagoon, the Palace of Fine Arts is composed of a wide, 1,100 ft (340 m) pergola around a central rotunda situated by the water.[12] The lagoon was intended to echo those found in classical settings in Europe, where the expanse of water provides a mirror surface to reflect the grand buildings and an undisturbed vista to appreciate them from a distance.

Ornamentation includes Bruno Louis Zimm's three repeating panels around the entablature of the rotunda, representing "The Struggle for the Beautiful", symbolizing Greek culture.[13] while Ulric Ellerhusen supplied the weeping women atop the colonnade[14] and the sculptured frieze and allegorical figures representing Contemplation, Wonderment and Meditation.[15][16]

The underside of the Palace rotunda's dome features eight large insets, which originally contained murals by Robert Reid. Four depicted the conception and birth of Art, "its commitment to the Earth, its progress and acceptance by the human intellect," and the four "golds" of California (poppies, citrus fruits, metallic gold, and wheat).[17]

Other surviving buildings of the exhibition

The Palace of Fine Arts was not the only building from the exposition to escape demolition. The Japanese Tea House (not to be confused with the Japanese Tea House that remains in Golden Gate Park, which dates from an 1894 fair) was purchased in 1915 by land baron E. D. Swift and was transported by barge down the Bay to Belmont, California where it stands to this day.[18] The Wisconsin and Virginia buildings were relocated to Marin County. The Ohio building was shipped to San Mateo County, where it survived until the 1950s.[19] The Column of Progress stood for a decade after the close of the Exhibition, but was then demolished to accommodate traffic on Marina Boulevard. Although not built on the exhibition grounds, the only other structure from it still standing in its original location is the San Francisco Civic Auditorium, known now as the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium.

The Legion of Honor Museum, in Lincoln Park, is a full-scale replica of the French Pavilion at the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition, which in turn was a three-quarter-scale version of the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur also known as the Hôtel de Salm in Paris by George Applegarth and H. Guillaume. At the close of the exposition, the French government granted Alma Spreckels permission to construct a permanent replica of the French Pavilion, but World War I delayed the groundbreaking until 1921.[20]

In popular culture

The Palace of Fine Arts has been seen in films such as Vertigo (1958),[21] Time After Time (1979),[22] The Room (2003),[23] and Twisted (2004).[24] It also served as the backdrop for set pieces in So I Married An Axe Murderer (1993)[25] and The Rock (1996).[26] Additionally, the Palace has appeared in the Indian films My Name is Khan (2010)[27] and Vaaranam Aayiram (2008).[28] It also appears in Season 7, Episode 2 of Mission: Impossible. It was incorporated into the imagery of the Sept of Baelor in Season 1, Episode 9 of Game of Thrones.

Lucasfilm headquarters was constructed near the Palace of Fine Arts, which has been noted for its similarity to the city of Theed on Naboo as it appears in the film Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace (1999).[29]

The structure was also featured as a peaceable landmark in the 2003 video game SimCity 4

In the 2000s, a smaller replica of the rotunda of the Palace of Fine Arts was built in Disney's California Adventure in Anaheim, serving as the entrance to a theater showing the film Golden Dreams about the history of California.[30]

Gallery

View of the rotunda from the northeast

View of the rotunda from the northeast Colonnade of the palace

Colonnade of the palace

References

- "National Register Information System – (#04000659)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- "City of San Francisco Designated Landmarks". City of San Francisco. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- "What's Happening With That Giant Building Behind the Palace of Fine Arts?". SF Weekly. 2019-01-17. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- Ting, Eric; Dowd, Katie; Amanda; Bartlett, a; SFGATE (2020-04-04). "Bay Area coronavirus updates: SF's Palace of Fine Arts will be temporary homeless shelter". SFGate. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco: Panama-Pacific International Exposition, San Francisco, 1915

- McCoy, Esther (1960). Five California Architects. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation. p. 6. ASIN B000I3Z52W.

- The Palace of Fine Arts: A Short History

- The Palace of Fine Arts: Rebuilding Archived October 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "A Short History". The Maybeck Foundation. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- Palace of Fine Arts, Official Website, background Archived January 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "SF City Hall was ahead of the curve in its coronavirus response. So why is it now failing the homeless?". SFChronicle.com. 2020-04-08. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- "A Treasury of World's Fair Art & Architecture: Palace of Fine Arts". Archived from the original on 2012-04-15. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- "Palace of Fine Arts, San Francisco Marina Neighborhood". Archived from the original on 2013-10-01. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- The Architecture and Landscape Gardening of the Exposition, A Pictorial Survey of the Most Beautiful Architectural Compositions of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition by Louis Christian Mullgardt

- Exhibition of American Sculpture Catalogue, 156th Street of Broadway New York, The National Sculpture Society 1923 p.55

- Macomber, Ben (1915). "The Palace of Fine Arts and its Exhibit, With the Awards". The Jewel City: Its Planning and Achievement; Its Architecture, Sculpture, Symbolism, and Music; Its Gardens, Palaces, and Exhibits. San Francisco and Tacoma: John H. Williams, Publisher.

- The Art of the Exposition by Eugen Neuhaus

- History of The Vans restaurant

- Lipsky, William (2005). San Francisco's Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Arcadia Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 0-7385-3009-3.

- "History of the Legion of Honor".

- "Vertigo – Palace of Fine Arts". Reel SF. December 11, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "Time After Time – Film Locations". Movie-Locations.com. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Scarlett, Jackson (September 23, 2012). "On Location: "The Room"". 7x7. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Rosenbaum, Dan (March 19, 2018). "Palace of Fine Arts – San Francisco, CA". San Francisco Travel. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Donat, Hank (2001). "San Francisco in Cinema: So I Married an Axe Murderer". MisterSF.com. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "The Rock – Film Locations". Movie-Locations.com. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "A Tribute to Shah Rukh Khan: My Name Is Khan". SFFILM. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "Vaaranam Aayiram". Where Was It Shot. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- Hill, Angela (September 15, 2015). "A 'Star Wars' Bay Area tour". The Mercury News. Retrieved November 11, 2018.

- "Golden Dreams". Disney's California Adventure. Walt Disney Company. Archived from the original on April 6, 2007. Retrieved May 11, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palace of Fine Arts, San Francisco. |