Coyote Creek (Santa Clara County)

Coyote Creek is a river that flows through the Santa Clara Valley in California, United States.

| Coyote Creek Arroyo del Coyote | |

|---|---|

Coyote Creek (lower right) where it flows into San Francisco Bay | |

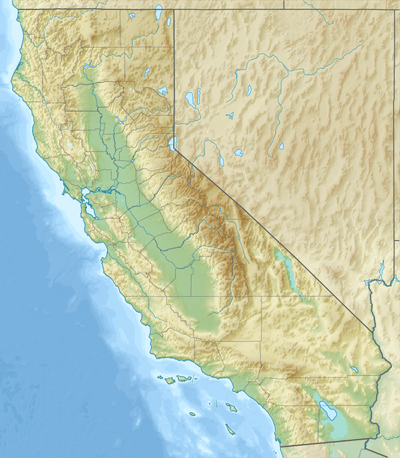

Location of the mouth of Coyote Creek in California | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Santa Clara County, Alameda County |

| City | San Jose, California |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | East Fork Coyote Creek |

| • location | 14 mi (20 km) northeast of Morgan Hill |

| • coordinates | 37°19′0″N 121°29′47″W[1] |

| • elevation | 2,630 ft (800 m) |

| 2nd source | Middle Fork Coyote Creek |

| • coordinates | 37°16′53″N 121°33′40″W[2] |

| • elevation | 3,400 ft (1,000 m) |

| Source confluence | Confluence of Middle and East Forks |

| • location | Henry W. Coe State Park |

| • coordinates | 37°10′24″N 121°29′42″W[3] |

| • elevation | 1,171 ft (357 m)[2] |

| Mouth | San Francisco Bay |

• location | 8 mi (13 km) west of Milpitas, California |

• coordinates | 37°27′26″N 122°2′56″W[3] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m)[3] |

| Length | 63.6 mi (102.4 km)confluence to mouth[4] |

History

Coyote Creek was originally named Arroyo del Coyote by Padre Pedro Font when the de Anza Expedition reached it on Sunday, March 31, 1776.[5][6]

Watershed

.jpg)

Although it is called a "creek", Coyote Creek is actually a river draining 320 square miles (830 km2) and running 63.6 miles (102.4 km)[4] from the confluence of its East Fork and Middle Fork to southeast San Francisco Bay.[5][7] The river's main source is on Mount Sizer near Henry W. Coe State Park and the surrounding hills in the Diablo Range, northeast of Morgan Hill, California. At the base of the Diablo Range, the creek is impounded by two dams, first Coyote Reservoir and then Anderson Lake. Nine major tributaries lie within the area that drains to these two reservoirs: Cañada de los Osos, Hunting Hollow, Dexter Canyon, and Larios Canyon Creeks drain to Coyote Reservoir; Otis Canyon, Packwood, San Felipe, Las Animas, and Shingle Valley Creeks drain to Anderson Lake.[7] Coyote Reservoir Dam was built across the active 1000-ft wide trace of the Calaveras fault by the Santa Clara Valley Water District (SCVWD) between 1934–36, storing 10,000 acre feet (12,000,000 m3) of water.[8]

From Anderson Lake, Coyote Creek continues northwards from Morgan Hill through Coyote Valley, the narrowest point between the Diablo Range and the coastal Santa Cruz Mountains, where it picks up Fisher Creek before entering San Jose. As Coyote Creek forms the eastern boundary of downtown San Jose, it winds its way into North San Jose. There, Silver Creek (including its tributaries Miguelita Creek and Thompson Creek), Penitencia Creek, and Berryessa Creek are all tributaries. Coyote Creek then bypasses the Newby Island landfill and empties into the San Francisco Bay.

There is a chain of parks along Coyote Creek called the Coyote Creek Park Chain, which contains the Coyote Creek Trail. The feasibility of a trail connecting the parks within this chain to Almaden Park was first examined in 1989.[9]

The river is managed by the SCVWD. In 1983, torrential rains caused by el Niño resulted in significant flooding of Coyote Creek in the Alviso neighborhood. The SCVWD, with advice from Santa Clara Basin Watershed Management Initiative (WMI) stakeholders, produced a stream stewardship plan for the Coyote Creek watershed in 2002. The plan includes over sixty projects to benefit flood protection, habitat enhancement, parks, and trails.

The Silver Creek Fault runs generally parallel to Coyote Creek.

Risk of Anderson Dam failure from earthquakes

Updated findings from an ongoing study of Anderson Dam were released in October, 2010, indicated that the dam could fail if a magnitude 7.25 earthquake occurred within 2 kilometers of the dam, potentially releasing a wall of water 35 feet (11 m) high into downtown Morgan Hill in 14 minutes, and 8 feet (2.4 m) deep into San Jose within three hours.[10] In response SCVWD has lowered the water to 54 percent full, which is 60 feet (18 m) below the dam crest.[11] According to the SCVWD, remediation of the problem will likely require lengthy construction that would take up to six years and cost as much as $100 million.[10]

Because Coyote Reservoir Dam was built right across the Calaveras fault and there is a substantial risk of a seismic-triggered landslide on the east side of the reservoir at the dam site, an earthquake could cause failure of this dam upstream of the Anderson Dam, and the release of water could increase risk of failure of the Anderson Dam.

On February 24, 2020, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered that Anderson Lake should be drained due to earthquake risk.[12]

2017 Coyote Creek flood

After unusually heavy rainfalls, on February 20 and 21, 2017, the Anderson Reservoir reached as high as 104 percent of capacity, creating a large flow over the spillway into Coyote Creek, which overflowed and flooded neighborhoods of San Jose along US Highway 101 between the reservoir and the south San Francisco Bay.[13]

The 2017 flood was the worst one since 1997. By 4 p.m. February 20, 2017, San Jose City opened an overnight shelter for residents who choose to voluntarily evacuate their homes in low-lying areas along Coyote Creek. Subsequent days, the city started issuing mandatory and advisory evacuation areas.[14] On February 21, 2017, five people were rescued from the Coyote Creek floodwaters at Los Lagos Golf Course. The flood on that day forced the closure of US 101 in Morgan Hill. Twenty-eight horses were stranded at Cooksy Family Stables in South San Jose and at nearby Happy Hollow Park & Zoo in San Jose. Nearly 500 homes were evacuated at Senter Road and Phelan Avenue. The entire William Street park was flooded. A parking garage at San Jose International Airport was also flooded.[15] About 14,000 people were forced out of their homes as a result of the flood. By February 23, 2017, nearly 4,000 people were still placed under evacuation orders. The creek reached a record height of 14.4 feet (4.4 m).[16]

In the weeks following the flood, citizen anger and anguish about the emergency response to the flood led to disagreements between the City of San Jose and the SCVWD.[17] At a hearing at City Hall on March 9, 2017, the City took some responsibility for giving late evacuation notices to residents but also blamed the water district for giving them flawed information.[17] For example, although the district had estimated that the flows would have to exceed 7400 cubic feet per second (209.6 m3 per second) for flooding to occur, flows peaked only slightly higher, at 7428 cubic feet per second (210.3 m3 per second), and only well after flooding had already commenced;[18] flooding had commenced at less than two thirds of the district's stated capacity.[19] Later in the month, the two parties disagreed about whose responsibility it is to maintain and repair the creek.[19] As of March 2017, the damage from the flood is estimated to cost more than $100 million to repair.[19]

Habitat and wildlife

Coyote Creek has historically, and still does support the most diverse fish fauna among the Santa Clara Valley Basin watersheds. It supports 10 to 11 native fish species out of the original 18. Species known to occur currently include Pacific lamprey (Lampetra tridentata), steelhead/resident rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), California roach, Hitch (Lavinia exilicauda), Sacramento blackfish (Orthodon microlepidotus), Sacramento pikeminnow, Sacramento sucker, three-spined stickleback, prickly sculpin (Cottus asper), riffle sculpin (Cottus gulosus), staghorn sculpin, and tule perch (Hysterocarpus traskii). Three species, the thicktail chub, splittail, and Sacramento perch have been extirpated from the drainage; the thicktail chub is extinct.[7]

1962 report indicated that Coyote Creek, from its mouth to the headwaters in Henry Coe State Park, was an historical migration route for steelhead trout. SCVWD studies have shown that Standish Dam and percolation ponds have posed barriers to outmigrating trout. Based on these results, the seasonal Standish Dam barrier has not been installed since 2000.[20] The on-channel percolation ponds constructed on Coyote Creek severely degrade steelhead habitat by harboring non-native fish predators, such as largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) which prey on salmonid fingerlings, and also by releasing warm water flows. Moving Ogier Ponds and Metcalf Percolation Ponds off-channel would significantly enhance rearing habitat for steelhead.[21]

In December 2017 Professor Jerry Smith of San Jose State University, announced that anadromous steelhead trout had been extirpated from Coyote Creek. These fish had spawned and reared in the perennial flows in the few miles below Anderson Dam since its construction. Smith's report noted that no young steelhead, known as smolts, had been able to outmigrate for several years because of lack of flows from dam releases in May, the month of outmigration, even in wet years such as 2017. Lack of outmigration coupled with immigration barriers such as the Singleton Road overcrossing, which acts as a permanent passage barrier to spawning runs in all but a handful of days even in wet years, led to the loss of the creek's reproducing steelhead trout population.[22]

The Chinook salmon run in Coyote Creek may be the most viable for restoration in the South Bay, since the breeding salmon in the Guadalupe River have severely declined subsequent to installation of extensive concrete channels in the river in downtown San Jose, California by the SCVWD. These are "fall run" fish primarily adapted to the Sacramento and San Joaquin River watersheds. Since Chinook salmon spawn in early winter and juveniles migrate to the ocean in their first spring, they are able to use habitats that turn very warm or have low water quality in summer.[21] In 2012, the Santa Clara Valley Habitat Plan reported that Chinook salmon currently spawn in Coyote Creek as well as the Guadalupe River and its tributaries.[23]

Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) were present in the Coyote Creek watershed until the 1950s, suggesting that some spawning and rearing habitat was located in the watershed downstream from Coyote Reservoir which was completed in 1936—blocking access to 120 square miles (310 km2) of upstream watershed. Historically, suitable habitat for coho salmon in the Coyote Creek watershed was likely restricted to the San Felipe Creek and Upper Penitencia Creek watersheds and possibly perennial reaches of Coyote Creek, and a few spring-fed tributaries upstream from Gilroy Hot Springs. Assuming the Coyote Percolation Reservoir was not a complete barrier to coho salmon; the construction of Anderson Dam in 1950 would have eliminated any coho salmon that occurred in the San Felipe Creek watershed that now flows into Anderson Lake. However, if the Coyote Creek Percolation Reservoir were a migration barrier, then only Upper Penitencia Creek would have provided suitable habitat for coho salmon after 1934.[24] San Felipe Creek currently contains habitat potentially suitable to coho salmon with low stream temperatures related to cool groundwater discharges in the Calaveras Fault zone.[25] During early June and late-July 1997, the senior author recorded water temperatures within the San Felipe Creek watershed within pools containing rainbow trout between 51.8 to 55.9 °F (11 to 13.3 °C) and 57.9 to 63.9 °F (14.4 to 17.7 °C), respectively. Zones of groundwater discharge along the Calaveras Fault zone that traverses the watershed maintain cool summer water temperatures. Upper Penitencia Creek, which enters lower Coyote Creek near its mouth and drains the steep coastal hills to the east also may have contained suitable coho salmon habitat.[24]

A 1962 California Department of Fish and Wildlife report indicates that golden beaver (Castor canadensis subauratus) lived in Coyote Creek historically.[26] This report is consistent with Alexander McLeod's report on the progress of the first Hudson's Bay Company fur brigade sent to California in 1829, "Beaver is become an article of traffic on the Coast as at the Mission of St. Joseph alone upwards of Fifteen hundred Beaver Skins were collected from the natives at a trifling value and sold to Ships at 3 Dollars".[27] Physical proof of golden beaver in south San Francisco Bay tributaries is a Castor canadensis subauratus skull in the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History collected by zoologist James Graham Cooper in Santa Clara, California on Dec. 31, 1855.[28] Beaver recolonized Coyote Creek in 2018 (see photo of beaver dam), apparently using the Bay to move from the Guadalupe River watershed.

A 1995 study showed high levels of toxic substances in receiving waters and sediments along urban areas of the creek versus undeveloped areas. This correlates to the density of storm drains suggesting that the pollution is from urban run-off.[29]

The Friends of Coyote Creek community group merged with the South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition in 2018.

See also

- List of rivers in California

- List of watercourses in the San Francisco Bay Area

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: East Fork Coyote Creek

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Middle Fork Coyote Creek

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Coyote Creek

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-04-05 at WebCite, accessed March 15, 2011

- Durham, David L. (1998). Durham's Place Names of California's San Francisco Bay Area: Includes Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo, Contra Costa, Alameda, Solano & Santa Clara counties. Word Dancer Press, Sanger, California. p. 620. ISBN 1-884995-14-4. Retrieved Jan 5, 2010.

- de Anza; Juan Bautista (1776). "Diary of Juan Bautista de Anza October 23, 1775 – June 1, 1776 University of Oregon Web de Anza pages". Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved Jan 5, 2010.

- "Coyote Creek Watershed, Santa Clara Valley Urban Runoff Pollution Prevention Program". Archived from the original on October 5, 2010. Retrieved Jan 5, 2010.

- J. David Rogers, Karl F. Hasselman. DAMS AND DISASTERS: a brief overview of dam building triumphs and tragedies in California's past (PDF) (Report). University of Missouri-Rolla. Retrieved 2010-11-01.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Feasibility Study for providing a trail between Alamden Park and the Coyote Creek Park Chain, Earth Metrics Incorporated, prepared for Parks and Recreation Department, City of San Jose, California, July 1989

- Sandra Gonzales (2010-10-13). "Study: Santa Clara County's Anderson Dam at risk of collapse in major earthquake". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- Marty Grimes (2010-10-13). Preliminary findings indicate Anderson Dam needs seismic retrofit (Report). Santa Clara Valley Water District. Archived from the original on 2010-11-12. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- "Feds order Santa Clara County's biggest reservoir to be drained due to earthquake collapse risk". The Mercury News. 2020-02-24. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- Pero, Aaron (February 22, 2017). "Water from Anderson Reservoir to blame for San Jose flooding". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "66354". February 24, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Sulef, Julia (February 22, 2017). "Storm: More rescues in Coyote Creek, Highway 17 closure". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Sam, Stephen (February 22, 2017). "News - Evacuees return to flood-ravaged homes in San Jose, CA - The Weather Network". The Weather Network. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Giwargis, Ramona (9 March 2017). "San Jose flood: Hundreds of victims at City Hall meeting demanding answers". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Kurhi, Eric; Giwargis, Ramona (February 22, 2017). "San Jose mayor: Clear 'failure' led to record flooding". Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- Herhold, Scott (15 March 2017). "Herhold: The background on San Jose flood dispute: The City of San Jose and the Santa Clara Valley Water District clash on significant points". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Leidy, R.A.; G.S. Becker & B.N. Harvey (2005). "Historical distribution and current status of steelhead/rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) in streams of the San Francisco Estuary, California" (PDF). Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration, Oakland, CA. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- Wayne D. Spencer; Sean J. Barry; Steven R. Beissinger; Joan L. Florsheim; Susan Harrison; Kenneth A. Rose; Jerry J. Smith; Raymond R. White (Dec 2006). Report of Independent Science Advisors for Santa Clara Valley Habitat Conservation Plan/Natural Community Conservation Plan (HCP/NCCP) (PDF) (Report). Retrieved Jan 14, 2010.

- Jerry J. Smith (December 17, 2017). Fish Population Sampling in 2017 on Coyote Creek (Report). San Jose State University. p. 39.

- Santa Clara Valley Habitat Plan (Report). Santa Clara Valley Habitat Agency. 2012. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- Robert A. Leidy, Gordon Becker, Brett A. Harvey (2005). Historical Status of Coho Salmon in Streams of the Urbanized San Francisco Estuary, California (PDF) (Report). California Department of Fish and Game. p. 243. Retrieved 2010-11-11.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Robert A. Leidy. Ecology, assemblage structure, distribution, and status of fishes in streams tributary to the San Francisco Estuary, California (Report). San Francisco Estuary Institute. Retrieved 2010-11-11.

- Skinner, John E. (1962). An Historical Review of the Fish and Wildlife Resources of the San Francisco Bay Area (The Mammalian Resources) (PDF). California Department of Fish and Game, Water Projects Branch Report no. 1. Sacramento, California: California Department of Fish and Game. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- Nunis, Doyce (1968). A. R. McLeod, Esq. to John McLoughlin, Esq. Dated Fort Vancouver 15 Feby. 1830, in The Hudson's Bay Company's First Fur Brigade to the Sacramento Valley: Alexander McLeod's 1829 Hunt. Fair Oaks, California: The Sacramento Book Collectors Club. p. 34.

- "Castor canadensis subauratus". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- Michael J. Kennish (1998). Pollution impacts on marine biotic communities. CRC Press. pp. 198–202. ISBN 0-8493-8428-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coyote Creek (Santa Clara County). |

- South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition website

- Friends of Los Gatos Creek facebook page

- Santa Clara Valley Water District Website

- Guide to Coyote Creek watershed from the Oakland Museum of California

- Middle Coyote Creek watershed map from the Oakland Museum of California

- Historic Coyote Creek watershed maps from the Oakland Museum of California

- Guadalupe – Coyote Resource Conservation District

- Santa Clara Basin Watershed Management Initiative (WMI)