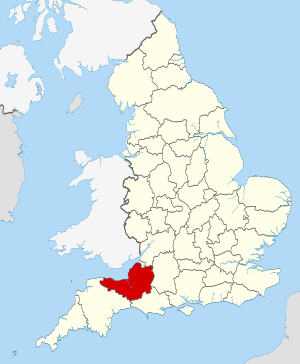

Geography of Somerset

The county of Somerset is in South West England, bordered by the Bristol Channel and the counties of Bristol and Gloucestershire to the north, and Wiltshire to the east, Dorset to the south, and Devon to the west. The climate, influenced by its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and the prevailing westerly winds, tends to be mild, damp and windy.

Somerset is predominantly a rural and agricultural county. The main upland areas are the Mendip Hills in the east and the Quantock Hills further west, the Blackdown Hills form the county's southern border, and Exmoor is on the western fringes. Between the Mendips and the Quantocks is the large area of flat, low-lying ground known as the Somerset Levels. The county's main rivers are the River Axe in the northeast, and the Rivers Brue and Parrett which flow northwestward through the levels into the Bristol Channel.

The landscape is largely determined by the underlying geology. The Carboniferous Limestone that forms the Mendips has been eroded to form gorges and caves. Exmoor is an extensive area of moorland and a National Park and the Somerset Levels contains wetland areas of international importance for birds. The Quantocks and the Blackdown Hills are Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and the island of Steep Holm, in the Bristol Channel, is one of many Sites of Special Scientific Interest. The M5 motorway runs diagonally across the county, which is served by a network of trunk roads. Several railway lines provide services to other parts of the United Kingdom, and Bristol Airport is in the northeast. Some traditional industries have declined, but the area is popular with tourists and famed for its Cheddar cheese and cider.

Physical geography

Somerset is a rural county in southwest England with an area of 4,171 square kilometres (1,610 sq mi). It is bounded on the north-west by the Bristol Channel, on the north by Bristol and Gloucestershire, on the east by Wiltshire, on the south-east by Dorset, and on the south west and west by Devon. The county divides into four main geological regions, spanning the Silurian, the Devonian and the Carboniferous to the Permian, that influence the landscape. The central area has broad, flat plains and there are several ranges of low hills.[1]

Topography

The main upland areas are the Mendip Hills in the northeast and the Quantock Hills further west. The Mendips run west to east between Frome and Weston-super-Mare, overlooking the Somerset Levels to the south and the Chew Valley and other tributaries of the River Avon to the north. They culminate in the promontory of Brean Down, only to crop up again in the Bristol Channel as the islands of Steep Holm and Flat Holm. Steep Holm is part of Somerset while Flat Holm is the most southerly point of Wales.[2] The Mendips are composed of Carboniferous Limestone and water erosion has created gorges, dry valleys, screes, swallets and caves as well as various karst features.[3]

The Quantocks extend northwards from the Vale of Taunton Deane, for about 15 mi (24 km) to the north-west, ending at Kilve and West Quantoxhead on the coast of the Bristol Channel. They form the western border of Sedgemoor and the Somerset Levels. The highest point is Wills Neck, at 384 metres (1,260 ft). The Quantocks consist of sedimentary rocks from the Devonian period, originally laid down under a shallow sea and slowly compressed into solid rock. The landscape consists of heathland with heather, gorse and bracken, ancient woodland and pasture land, with steep slopes and wooded combes.[4]

The Blackdown Hills form the southerly border of the county with North Devon. They are composed of Upper Greensand and form a fairly level plateau with steep slopes with incised valleys to the north but more gentle slopes to the south. Their highest point is Staple Hill (315 metres (1,033 ft)).[5] Exmoor is a large upland area straddling Somerset and North Devon, close to the Bristol Channel. It is composed from the Exmoor Group of sedimentary rocks and is overlain by moorland with wet, acid soil.[6] The Exmoor coastline has rocky headlands, ravines, waterfalls and towering cliffs that are the highest sea cliffs on mainland Britain. Exmoor also contains the highest point in the county, Dunkery Beacon at 520 metres (1,710 ft).[7]

Near the coast, halfway between the Quantocks and the Mendips, and lying parallel to them, is the low ridge of the Polden Hills. On either side is a coastal plain and wetlands area known as the Somerset Levels, an area of about 70,000 hectares (170,000 acres),[8] much of which is about6 metres (20 ft) above sea level. The northeasterly part of the Levels is drained by the Axe and Brue, and the southwesterly part by the Parrett and its main tributary, the Tone. This part of the Levels has traditionally been known as Sedgemoor, and to the east is Glastonbury Tor, an isolated hill projecting from the low-lying plain.[1]

Water features

The north coast is gently shelving with low cliffs and long stretches of sandy beach, some sections of which, especially in the northwest, are muddy. The principal coastal feature is Bridgwater Bay, and the only important harbour is at the mouths of the Parrett.[1] The main rivers in Somerset rise in the hills and flow northwards and westwards into the Bristol Channel; these are the Axe, Brue, Parrett and its tributaries, and Exe.[1] The source of the River Axe is at Wookey Hole Caves in the Mendip Hills. It flows through a ravine and then west through the village of Wookey. It splits into two parts which subsequently recombine, and flows across the moors, through Lower Weare and to the south of Loxton. It passes between Uphill Cliff and Brean Down and reaches the sea at Weston Bay; it forms the northern boundary of the county.[2]

The River Brue flows through the Somerset Levels to the east of the Polden Hills. It rises in hills near the southern border of the county, flows through Bruton, where it is joined by the River Pitt, and on through Baltonsborough. The lower reaches have been diverted into a channel that joins the Parrett at Burnham-on-Sea in Bridgwater Bay. There is a raised bog in the central Brue valley and the surrounding area is a mosaic of swamps, meres and alder woodland.[9] The River Parrett rises in the hills around Chedington in Dorset and flows northwestwards past Aller, Somerset, and through the Somerset Levels to Bridgwater, after which it becomes an estuary with its mouth at Burnham-on-Sea. The river has a tidal bore, similar to that in the River Severn. The Somerset Levels are only a few feet above sea level and liable to flooding. They are drained by ditches and channels that drain into the Parrett including the King's Sedgemoor Drain, just south of the Polden Hills.[9]

The River Tone rises in the Brendon Hills, and is dammed near its source to form the Clatworthy Reservoir. It flows roughly eastwards, through Taunton to join the River Parrett above Bridgwater. The River Exe rises on Exmoor in Somerset, about 5 mi (8 km) south of the Bristol Channel, but flows more or less directly south, so that most of its course lies in Devon and its mouth is on the south coast.[2]

Hills

Urban areas

Somerset is largely rural and the two main centres of population, Bath and Weston-super-Mare, were transferred to the unitary authority districts of Bath and North East Somerset and North Somerset respectively, in 1996 but are still part of the ceremonial county.[10] The Somerset Levels are liable to flooding and the only significant towns are Glastonbury and Street which occupy slightly elevated locations on the Polden Hills.[11]

Other large towns are Wells, Taunton, the county town, Bridgwater, Yeovil and Frome.[1] Wells is at the foot of the Mendip Hills and was built on the site of a Roman settlement. It became important as a trading centre. It has been described as England's smallest city because of Wells Cathedral.[11] Taunton occupies an inland site on the banks of the River Tone and has been in existence since at least Saxon times. It is home to the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office and the regional headquarters of such organisations as Defra and the Charity Commission for England and Wales.[12]

Bridgwater is at the mouth of the River Parrett, 10 miles (16 km) inland and the lowest crossing place above the estuary. It was mentioned in the Domesday Book and was once a major port and trading centre, and is still a mainly industrial town.[11] Yeovil is in the middle of the Yeovil Scarplands, an upland area on the southern borders of the county. It was settled in prehistoric times and Yeovil is also mentioned in the Domesday Book. The town is a centre for the aviation and defence industries and a major employer is the helicopter manufacturer AgustaWestland.[13] Frome, another ancient settlement, occupies a site at the foot of the Mendips overlooking the River Frome. The town was dependent on the woollen industry, but is now associated with metal-working and printing, and large numbers of residents commute to Bristol and Bath.[14]

Geology

The oldest rocks are of Silurian age (443–419 million years ago). They make up a sequence of lavas, tuffs (volcanic ash), shales and mudstones in a narrow outcrop to the northeast of Shepton Mallet in the eastern Mendip Hills.[15] Rocks from the Devonian (419–359 million years ago) are found across much of Exmoor,[16] the Quantocks, and in the cores of the folded masses that form the Mendip Hills.[17]

Carboniferous Period (359–299 million years ago) rocks are represented by the Carboniferous Limestone that forms the Mendip Hills, rising abruptly out of the flat landscape of the Somerset Levels. The limestones contain fossils of crinoids (sea-lilies), corals and brachiopods, providing evidence of the abundant marine life that existed in the shallow tropical seas that covered these areas at that time. Some hills, such as in the Mendips, are in excess of 800 feet (240 m) above sea level, and from them flow rivers of substantial erosive power. Examples of erosion may be seen at Cheddar Gorge and the caves within it, where the soft limestone has been scoured into gorges and caverns of great depth and length.[18] At the end of the Permian (299–252 million years ago) and Triassic periods (252–201 million years ago), the Variscan orogeny resulted in the uprising of several mountainous areas including Dartmoor to the south, Exmoor, the Quantocks and the Mendips.[17]

Much of the landscape falls into types determined by the underlying geology. These landscapes are the limestone karst and lias of the north, the central clay vales and wetlands, the oolites of the east and south, and the Devonian sandstone of the west.[19] To the north-east of the Somerset Levels, the Mendips are moderately high limestone hills. The area of the central and western Mendip Hills was designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1972 and covers 198 km2 (76 sq mi). The main habitat of these areas is calcareous grassland, with some arable agriculture. The Somerset Coalfield is part of a larger coalfield stretching into Gloucestershire. To the north of the Mendip hills is the Chew Valley and to the south, on the clay substrate, are broad valleys supporting dairy farming and rivers draining into the Somerset Levels.[20]

Climate

Along with the rest of South West England, Somerset has a temperate climate which is generally wetter and milder than most of England.[21] The annual mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50 °F). Seasonal temperature variation is less extreme than most of the United Kingdom because of the moderating influence of the adjacent areas of sea. The summer months of July and August are the warmest with mean daily maxima of approximately 21 °C (70 °F). In winter mean minimum temperatures of 1 °C (34 °F) or 2 °C (36 °F) are common.[21] In summer the Azores high pressure system affects the south-west of England, but convective cloud sometimes forms inland, reducing the number of hours of sunshine. Annual sunshine rates are slightly less than the regional average of 1,600 hours.[21] Most rainfall in autumn and winter is caused by the arrival of Atlantic depressions, which bring moisture-laden air from the southwest and west. In summer, a large proportion of the rainfall is caused by sunlight heating the ground, leading to convection and the formation of showers and thunderstorms. Average rainfall is around 700 mm (28 in), and eight to fifteen days of snowfall is typical. November to March has the highest mean wind speeds, and June to August the lightest winds. The predominant wind direction is from the south-west.[21]

Early settlement

In much of the area bordering the wetlands, an abundance of produce, of great variety, can be cultivated. The green and varied landscape provides good grazing for livestock. In some areas the carboniferous limestone and the Dolomitic Conglomerate have been mineralised with lead and zinc ores. Evidence of early settlement comes from the Sweet Track, which was built from timber felled in the winter of 3807–06 BC,[22] and lowland villages such as Glastonbury Lake Village and hill forts and ancient settlements on hills, many of which date from the Iron Age. From the time of the Romans until 1908, the Mendip Hills were an important source of lead.[23] These areas were the centre of a major mining industry; this is reflected in areas of contaminated rough ground known locally as "gruffy"; the word "gruffy" is thought to derive from the closely packed shafts that were sunk to extract lead ore from veins near the surface.[24][25] Calamine, manganese, iron, copper and barytes were also mined.[26]

Many hillsides, such as at Cadbury Castle, Ham Hill and Maes Knoll, and sheltered valleys provided defensible locations for early human settlements. Trade was established early. The large tidal variation provided access inland, a key factor in distributing goods and produce, using rivers such as the Parrett and Avon.[27][28] The tidal range of 43 feet (13 m),[29] is second only to Bay of Fundy in Eastern Canada.[30][31]

Land use

Somerset is a predominantly agricultural county with arable cropping and dairy farming; Cheddar cheese is a well-known product. The main field crops include wheat, barley, oats and root crops, and extensive orchards produce cider apples. Large numbers of cattle and sheep are kept, and Exmoor ponies and red deer roam on the open moorland in the west of the county.[1] Coal was at one time mined in the county; the Somerset Coalfield stretched from Cromhall to the Mendips, and from Nailsea to Bath. The last two pits, at Kilmersdon and Writhlington, closed in 1973.[32] Minerals mined here at one time included iron, lead, zinc, slate and fuller's earth.[1]

The Mendips are the most southerly Carboniferous limestone uplands in Britain. They are composed of three major anticlinal structures, each with a core of older Devonian sandstone and Silurian volcanic rocks. The limestone is quarried for building stone and the other rocks for use in road construction and as a concrete aggregate. Sand, gravel and peat are extracted in other parts of the county.[33]

The Somerset Levels between the ancient towns of Glastonbury and Wells have traditionally been used for growing withies, flexible, strong willow stems, used for many centuries for making furniture, baskets and fencing. Willow has been cut, processed and used on the Levels since humans moved into the area.[34] Fragments of willow basket were found near Glastonbury Lake Village, and it was used in the construction of several Iron Age causeways.[35] The industry thrives in preserved areas of wetlands, and there is a Willows and Wetlands Visitor Centre at Stoke St Gregory.[34]

Besides farming and its associated industries, including making cider, cheese and yoghurt, and peat extraction, the county has little industry. It has been involved in the manufacture of helicopters, some heavy industries related to defence, quarrying and the mining of gravels and sands, brick-making and tile-making, and the manufacture of slippers, boots and shoes, but many of these industries have declined.[1] Tourism is one of the main sources of income.[36]

Protected areas

The Gordano Valley west of the Port of Bristol stretches past the coastal towns of Portishead and Clevedon. It has been designated as a National nature reserve,[37] and much of it may be observed by travellers on the south bound M5 motorway. The Chew Valley is another managed water way and woodland in the same area. The Avon Valley to the East of Bristol continues to Bath and beyond towards Wiltshire. The western end of the Mendip Hills has, since 1972, been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) under the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949.[38][39] The Blackdown Hills were designated an AONB in 1991,[40] and the Quantock Hills have held the status since 1956, the first such designation in England under the Act.[41]

The Somerset Levels is a wetland area of international importance, with large numbers of wading birds overwintering there.[34]

Exmoor is a National Park straddling two counties with 71% in Somerset and 29% in Devon. The area of the park, which includes the Brendon Hills and the Vale of Porlock is 692.8 square kilometres (267.5 sq mi) of hilly open moorland and the park has 55 kilometres (34 mi) of coastline.[42]

Steep Holm is protected as a nature reserve and Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI). [43] A large number of sea bird are resident or visit the island, particularly European herring gulls (Larus argentatus) and Lesser black-backed gulls (Larus fuscus),[44] but it is mainly preserved for its botanical interest; it is the only site in the United Kingdom where wild peonies grow.[45]

Green belt

The county contains several miles wide sections of the Avon green belt area, which is primarily in place to prevent urban sprawl from the Bristol and Bath built up areas into the rural areas of North Somerset[46], Bath and North East Somerset[47], and Mendip[48] districts in the county, as well as maintaining surrounding countryside. It stretches from the coastline between the towns of Portishead and Clevedon, extending eastwards past Nailsea, around the Bristol conurbation, and through to the city of Bath. The green belt border intersects with the Mendip Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) along its south boundary, and meets the Cotswolds AONB by its eastern extent along the Wiltshire county border, creating an extended area protected from inappropriate development.

Local government

The ceremonial county of Somerset is subdivided into five districts and two unitary authority areas (whose councils combine the functions of a county and a district). The five districts are West Somerset, South Somerset, Taunton Deane, Mendip and Sedgemoor, and the two unitary authorities are North Somerset and Bath & North East Somerset.[49]

Communications

Somerset has approximately 6,530 km (4,060 mi) of roads.[50] The M5 motorway runs diagonally across the county, from northeast to southwest. Other main arterial routes include the A39, the A303, the A37, the A38, the A358 and the A361,[51] but many rural villages can only be accessed via narrow country lanes.[50]

The West of England Main Line links London Waterloo and Basingstoke to Exeter through Yeovil Junction, and the Bristol to Exeter line, part of the Great Western Main Line. The Heart of Wessex Line from Bristol Temple Meads to Weymouth, and the Reading to Taunton Line serve other parts of the county. The key train operator is Great Western Railway, and other services are provided by CrossCountry and South Western Railway. The West Somerset Railway linking Bishops Lydeard and Minehead, is the longest heritage railway in England.[52] Bristol Airport, beside the A38 in North Somerset, provides national and international air services.[51]

References

- E. F. Bozman, ed. (1967). "11: Santa Catarina – Thomas à Kempis". Everyman's Encyclopedia. J. M. Dent & Sons. pp. 295–296.

- Fullard, Harold, ed. (1973). Philips' Modern School Atlas. George Philip and Son. p. 24. ISBN 0-540-05278-7.

- "Mendip Hills Natural Area profile" (PDF). English Nature. January 1998. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "The Quantocks" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "Blackdown Hills". Landscape. Natural England. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- "Geology". Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- "Exmoor National Park Facts and Figures". Exmoor National Park. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "What are the Somerset Levels?". BBC News, Somerset. 7 February 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Dunning, Robert, ed. (2004). "A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 8: The Poldens and the Levels". British History Online. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "The problem of "county confusion" – and how to resolve it". County-Wise. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Else, David (2010). Somerset. Great Britain. Lonely Planet. pp. 339–346. ISBN 978-1-74104-491-1.

- "Charity Commission for England and Wales". Megabiz.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Helicopters". Leonardo. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "Frome Community Plan". Mendip District Council. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Roche, David (2004). "Moons Hill Quarry, Stoke St Michael, Shepton Mallet". Geodiversity Audit of Active Aggregate Quarries. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- "Geology of Exmoor". Everything Exmoor. Retrieved 21 August 2008.

- Hardy, Peter (1999). The Geology of Somerset. Ex Libris. ISBN 978-0-948578-42-7.

- Scott, P. W.; Bristow, Colin Malcolm; Geological Society of London (2002). Industrial Minerals and Extractive Industry Geology. Geological Society of London. pp. 363–364. ISBN 978-1-86239-099-7.

- "Somerset Geology". Good Rock Guide. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Mendip Hills AONB. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- "South West England: climate". Met Office. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- "The day the Sweet Track was built". New Scientist, 16 June 1990. Retrieved 26 October 2007.

- Toulson, Shirley (1984). The Mendip Hills: A Threatened Landscape. London: Victor Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-03453-X.

- "GB Gruffy Nature Reserve". Somerset Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- Coysh, A.W.; Mason, E.J.; Waite, V. (1977). The Mendips. London: Robert Hale Ltd. ISBN 0-7091-6426-2.

- Gough, J.W. (1967). The mines of Mendip. David & Charles.

- Edited by William Page (1992). Dunning, R. W. (ed.). Andersfield, Cannington, and North Petherton Hundreds (Bridgwater and Neighbouring Parishes). The Victoria History of the County of Somerset. VI. Oxford: Oxford University Press for the University of London Institute of Historical Research. ISBN 0-19-722780-5.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Fitzhugh, Rod (1993). Bridgwater and the River Parrett: in old photographs. Alan Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-0518-2.

- "Severn Estuary Barrage". UK Environment Agency. 31 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- Chan, Marjorie A.; Archer, Allen William (2003). Extreme Depositional Environments: Mega End Members in Geologic Time. Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America. p. 151. ISBN 0-8137-2370-1.

- "Coast: Bristol Channel". BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- "A Brief History of the Bristol and Somerset Coalfield". The Mines of the Bristol and Somerset Coalfield. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- "Somerset Minerals Plan". Somerset County Council. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "Willows and Wetlands Visitor Centre". Visit Somerset. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- "Somerset Levels". BBC Radio 4 – Open Country. Retrieved 10 June 2007.

- "Employers in Somerset". Somerset Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Gordano Valley NNR". Natural England. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "About the AONB". Mendip Hills AONB. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- "Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)". Somerset County Council. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- "What is an AONB". Blackdown Hills AONB. Archived from the original on 2008-06-01. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- "Welcome to the Quantock Hills AONB Service Website". Quantock Hills AONB. Somerset County Council. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- "Moor Facts". Exmoor-nationalpark.gov.uk. 19 October 1954. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- "Citation – Steep Holm" (PDF). English Nature. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Lewis, Stanley (1936). "Birds of the Island of Steep Holm" (PDF). British Birds. xxx: 219–223.

- "Steep Holm Island, Somerset". The Wildlife Trusts. Archived from the original on 2015-07-12. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "North Somerset Futures Local Development Framework - North Somerset Green Belt Assessment - South West of Bristol" (PDF). www.n-somerset.gov.uk.

- "Bath & North East Somerset Green Belt Review" (PDF). www.bathnes.gov.uk.

- "PROTECTING AND ENHANCING ENVIRONMENTAL ASSETS". www.mendip.gov.uk.

- "The Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995". HMSO. Archived from the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- "About The Service". Devon and Somerset Fire and Rescue. Archived from the original on 23 June 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- AA Concise Road Atlas of Britain. AA Publishing. 2016. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-7495-7743-8.

- "West Somerset Railway". Visit Somerset. Retrieved 10 September 2016.