Bridgwater Bay

Bridgwater Bay is on the Bristol Channel, 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) north of Bridgwater in Somerset, England at the mouth of the River Parrett and the end of the River Parrett Trail. It stretches from Minehead at the southwestern end of the bay to Brean Down in the north. The area consists of large areas of mudflats, saltmarsh, sandflats and shingle ridges, some of which are vegetated. It has been designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) covering an area of 3,574.1 hectares (35.741 km2; 13.800 sq mi)[1] since 1989,[2] and is designated as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention.[3] The risks to wildlife are highlighted in the local Oil Spill Contingency Plan.[4]

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

Bridgwater Bay near the mouth of the River Parrett | |

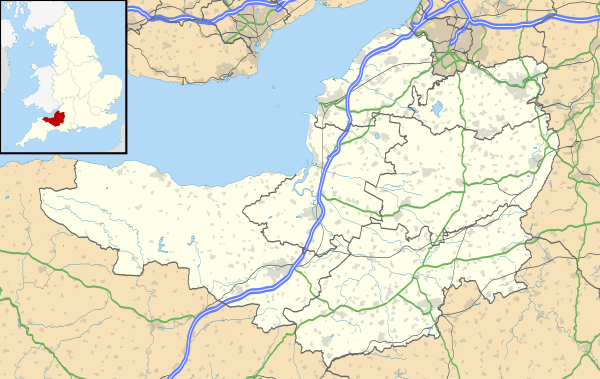

Location within Somerset | |

| Area of Search | Somerset |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | ST290480 |

| Coordinates | 51.2166°N 3.2833°W |

| Interest | Biological |

| Area | 3,574.1 hectares (35.741 km2; 13.800 sq mi) |

| Notification | 1989 |

| Natural England website | |

Several rivers, including the Parrett, Brue and Washford, drain into the bay. Man-made drainage ditches from the Somerset Levels, including the River Huntspill, also run into the bay. The mud flats provide a habitat for a wide range of flora and fauna. These include some nationally rare plants, beetles and snails. It is particularly important for over-wintering waders and wildfowl, with approximately 190 species recorded including Eurasian whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa), dunlin (Calidris alpina) and wigeon (Anas penelope). Fishing has taken place using shallow boats, known as flatners, and fixed wooden structures for hundreds of years. It was also the last site in England used for 'mudhorse fishing'. There are several small harbours along the coast.

The low-lying areas of the bay have been subject to flooding, including the Bristol Channel floods of 1607 and many times since particularly around the Steart Peninsula. In response to this threat sea walls have been built at several points including at Burnham-on-Sea, Berrow and Blue Anchor to Lilstock Coast. The extensive mud flats and high tidal range have been the cause of several drownings and rescue services are now provided by the Burnham Area Rescue Boat.

Geography

Bridgwater Bay forms a portion of the coastline of Somerset on the southern side of the Bristol Channel stretching from the Quantock Hills at the south western end to Brean Down at the northern end. Around the coastline is a wave-cut platform of Jurassic Blue Lias. Several rivers flow into the bay, the main ones being the Parrett, Brue and Washford, along with the man-made River Huntspill. Major features and settlements along the coastline, running from north east to south west, include: Brean, Berrow, Burnham on Sea, the mouth of the River Parrett, the Steart Peninsula, Lilstock, East Quantoxhead and Watchet. Sand dunes at Berrow and a shingle ridge at Steart have been created by winds blowing from the west. On the beach near Stogursey are the remains of a submerged forest dated to 2500 B.C.[5] - 6500 BC.[6]

Brean Down is a promontory marking the eastern end of the bay. Made of carboniferous limestone, it is a continuation of the Mendip Hills, and two further continuations are the small islands of Steep Holm and Flat Holm. It is owned by the National Trust, and is rich in wildlife, history and archaeology, as well as being a Site of Special Scientific Interest in its own right.[7] It is bounded by steep cliffs and, at its seaward point, Brean Down Fort built in 1865 and then re-armed in the Second World War. There is evidence of an Iron Age hill fort, prehistoric barrows, field systems[8] and a pagan shrine. The shrine dating from pre-Roman times[9] was re-established as a Romano-Celtic style temple in the mid-4th century and probably succeeded by a small late-4th century Christian oratory.[10] In 1897, following wireless transmissions from Lavernock Point in Wales to Flat Holm, Guglielmo Marconi moved his equipment to Brean Down and set a new distance record for wireless transmission.[11][12]

At low tide large parts of the bay become mud flats 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) wide, due to the tidal range of 15 metres (49 ft),[13] second only to the Bay of Fundy in Eastern Canada.[14][15] The intertidal mud flats are, as a result, potentially dangerous and it is not uncommon for the emergency services to mount rescue operations on them. Following the death of Lelaina Hall off Berrow in 2002, a local fund raising campaign succeeded in purchasing a Swedish-built BBV6 rescue hovercraft.[16][17][18] The hovercraft is operated by Burnham Area Rescue Boat (BARB) in Burnham-on-Sea.[19] Much of the coastline within the western part of the reserve is accessible via a waymarked public footpath,[20] and the South West Coast Path begins at Minehead at the western end of the bay. The tidal range holds potential for energy generation and plans for a tidal barrage in the bay have been considered.[21]

Hinkley Point is a headland extending into Bridgwater Bay 5 miles (8.0 km) west of Burnham-on-Sea, close to the mouth of the River Parrett. The landscape of Hinkley Point is dominated by two nuclear power stations: Hinkley Point A - Magnox (now closed) and Hinkley Point B - AGR. A third, twin-unit European Pressurized Reactor (EPR) reactor is planned, and will become Hinkley Point C.[22]

Man-made sea defenses include a sea wall at Burnham-on-Sea and a 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) section south from Brean Down. There are also sand dune belts which are managed for their protective function and as a wildlife habitat.[23] There are some concerns that the proposed Severn Barrage could leave some sites high and dry, and others permanently under water.[24] The Steart Peninsula has flooded many times during the last millennium. The most severe recent floods occurred in 1981. By 1997, a combination of coastal erosion, sea level rise and wave action had made some of the defences distinctly fragile and at risk from failure. As a result, in 2002 The Environment Agency produced the Stolford to Combwich Coastal Defence Strategy Study to examine options for the future.[25]

The foreshore at Watchet, which lies at the mouth of the Washford River, and on the edge of Exmoor National Park, is rocky, but has a small harbour. The cliffs between Watchet and Blue Anchor show a distinct pale, greenish blue colour, resulting from the coloured alabaster found there. The name "Watchet" or "Watchet Blue" was used in the 16th century to denote this colour.[26][27]

East Quantoxhead used to have a small harbour which brought in limestone for local limekilns and exported alabaster. It is thought that it was also used for smuggling.[28]

At Kilve are the remains of a red brick retort, built in 1924, when it was discovered that the shale found in the cliffs was rich in oil. The beach is part of the Blue Anchor to Lilstock Coast SSSI (Site of Special Scientific Interest). Along this coast the cliffs are layered with compressed strata of oil-bearing shale and blue, yellow and brown lias embedded with fossils. In 1924 Forbes-Leslie founded the Shaline Company to exploit them. This retort house is thought to be the first structure erected here for the conversion of shale to oil but the company was unable to raise sufficient capital and this is now all that remains of the anticipated Somerset oil boom.[29]

Fishing

The intertidal mud flats of the bay have a long history of use for fishing, with structures on Stert Flats being dated by dendrochronological analysis to between 932 and 966.[6] It is the last site in England used for 'mudhorse fishing' in which a wooden sledge is propelled across the mudflats to collect fish from nets.[24] Catches include: Thinlip mullet,[30] plaice, dogfish, cuttlefish, skate, shrimp, prawns, sea bass, and sole.[31] Watchet Boat Museum displays the unusual local flatner boats which were used for fishing in the bay, along with associated artefacts.[32]

Ecology

At low tide extensive areas of mudflats (the Steart and the Berrow Flats) are exposed, providing important feeding and over-wintering grounds for waders (shorebirds). Invertebrate fauna including six nationally rare species and eighteen nationally scarce species can be found in the ditches and ponds around the shores.[2] Consequently, Bridgwater Bay is a National Nature Reserve, and is managed by Natural England.[33] Some of the potential risks to wildlife are highlighted in the local Oil Spill Contingency Plan.[4]

Brean Down, Berrow Dunes and Blue Anchor to Lilstock Coast Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are included in the national nature reserve[2] which is designated as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention.[34] It is also a Nature Conservation Review Grade 1* site, meaning it is included in Derek Ratcliffe's book listing the most important places for nature conservation in Great Britain.[2]

Flora

Common cord-grass (Spartina anglica) was planted in the area in the 1990s. It can now be found on surrounding marshes where it has invaded the fronting mudflats.[35] The Spartina is generally shorter in the bay than at other sites due to the high tides and the turbidity of the water, reaching around 30 centimetres (11.8 in) as opposed to 150 centimetres (59.1 in) elsewhere.[36] On higher ground common saltmarsh-grass (Puccinellia maritima) can be found along with sea aster (Aster tripolium). Where the land is ungrazed, common reed (Phragmites australis) often forms a zone above the sea aster. Where the upper marsh is grazed by cattle red fescue (Festuca rubra) and creeping bent (Agrostis stolonifera) are found. The area of marsh furthest from the sea supports Sea couch (Agropyron pungens) and sea club-rush (Scirpus maritimus).[2]

The nationally scarce bulbous foxtail (Alopecurus bulbosus), slender hare's-ear (Bupleurum tenuissimum) and sea barley (Hordeum marinum) are grazed by sheep on the marshes around the bay. Around Stert Island the nationally rare compact brome (Bromus madritensis) and nationally scarce Ray's knotgrass (Polygonum oxyspermum) can be found.[2][3]

The ditches are populated with aquatic and bankside plant species. These include the nationally restricted rootless duckweed (Wolffia arrhiza). Other uncommon species such as frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae) and water fern (Azolla filiculoides) can also be found. The nationally restricted brackish water-crowfoot (Ranunculus baudotii) and sea clubrush (Scirpus maritimus) indicate the slightly brackish nature of the water.[2]

Brean Down is a site for the nationally rare white rock-rose (Helianthemum apenninum), which occurs in abundance on the upper reaches of the grassy south-facing slopes.[37] Some of the broomrapes growing near Bridgwater Bay, which were originally thought to be oxtongue broomrape (Orobanche artemisiae-campestriae), are now no longer believed to be this species, but atypical specimens of ivy broomrape (Orobanche hederae)[38] Other plants on the southern slopes include the Somerset hair grass, wild thyme, horseshoe vetch and birds-foot-trefoil.[38] The northern side is dominated by bracken, bramble, privet, hawthorn, cowslips and bell heather.[38]

Fauna

Five Red Data Book invertebrate species have been recorded in the area. These include: the soldier flies Odontomyia ornata and Stratiomys singularior, hover fly Lejops vittata, the great silver water beetle (Hydrophilus piceus), and the water beetle Hydrovatus clypealis. Nationally scarce species include the aquatic snail Gyraulus laevis, the hairy dragonfly (Brachytron pratense), and the ladybird Coccidula scutellata.[2]

Over 190 species of birds have been identified near the bay, some of which use it as a feeding ground during their migrations. Waders and wildfowl often over-winter on the reserve.[3] The populations of Eurasian whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus) and black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa) are internationally important. Significant populations of dunlin (Calidris alpina) and wigeon (Anas penelope) also frequent the bay.[39][40][2][3][41] In early winter the wigeon select Puccinellia maritima in preference to Agrostis stolonifera and Festuca rubra.[42][43] Avocets have become regular autumn and winter visitors to the area in recent years, favouring the lower reaches of the River Parrett,[44][39] and, for the first time in over 50 years, bred on the reserve in 2012.[3]

Rare vagrant species spotted in the area include lesser yellowlegs, white-rumped sandpiper, Pallid Harrier (in spring) and Richard's pipit (in autumn).[45][39][46][39][47][48][49][50][51] The birds seen on Brean Down include peregrine falcon, jackdaw, kestrel, collared and stock doves, whitethroat, linnet, stonechat, dunnock and rock pipit.[52][53][54] There are also several species of butterfly, including chalkhill blue, dark green fritillary, meadow brown, marbled white, small heath, and common blue.[55][56]

References

- "Bridgwater Bay SSSI". Natural England. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "SSSI citation sheet" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. English Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- "Bridgwater Bay NNR". National Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Oil spill contingency plan". Sedgemoor Council. Archived from the original on 3 June 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- "Stogursey". Victoria County History. British History Online. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- "Severn Estuary rapid coastal zone assessment". Historic England. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- "Brean Down" (PDF). English Nature. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2008.

- Adkins, Lesley and Roy (1992). A field Guide to Somerset Archeology. Stanbridge: Dovecote press. ISBN 978-0-946159-94-9.

- Dunning, Robert (1983). A History of Somerset. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-0-85033-461-6.

- Aston, Mick; Burrow, Ian (1982). The Archaeology of Somerset. Taunton: Somerset County Council.

- "Marconi: work of a radio pioneer". BBC. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "First international wireless message Bristol Channel". Carnet De Vol. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- "Severn Estuary Barrage". UK Environment Agency. 31 May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- Chan, Marjorie A.; Archer, Allen William (2003). Extreme Depositional Environments: Mega End Members in Geologic Time. Boulder, Colorado: Geological Society of America. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-8137-2370-9.

- "Coast: Bristol Channel". BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2007.

- Alleyne, Richard; Martin, Nicole (25 June 2002). "Rescuers tell of desperate fight to save mud flats girl". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "'Sad, tragic' case of girl's drowning". BBC News. 24 October 2002. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Earl of Wessex to unveil Lelaina plaque at BARB". This is Somerset. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Spirit of Lelaina lives on". BBC News. 22 March 2003. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Bridgwater Bay National Nature Reserve". Breathing Places. BBC. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- "Bridgwater Bay". Tidal Lagoon Power. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "New dawn for UK nculear power". WNN. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- "Bridgwater Bay Natural Area Profile" (PDF). Natural England. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- "Matt Baker goes mad for mud, fish and relics in Bridgwater Bay". Open Country. BBC. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- "Stolford to Combwich Coastal Defence Strategy Study" (PDF). Environment Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 31 October 2007.

- Leete-Hodge, Lornie (1985). Curiosities of Somerset. Bodmin: Bossiney Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-906456-99-6.

- "Article from Issue Number 12/1 February 2005". Open University Geological Society (London Branch). Archived from the original on 18 February 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- Farr, Grahame (1954). Somerset Harbours. London: Christopher Johnson. pp. 123–124. ASIN B0000CIU0I.

- "Oil retort house". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- "Estuarine monitoring - Hinkley Point report, 2000–2001". Pisces Conservation. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- Fort, Matthew (21 May 2008). "Around Britain with a fork". The Guardian. Guardian Newspapers. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- "Flatners". Watchet Boat Museum. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- "Bridgwater Bay NNR". Natural England. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Bridgwater Bay NNR". National Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- "Visiting Steart". Burnham on Sea.com. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Morley, J.V. (July 1973). "Tidal Immersion of Spartina Marsh at Bridgwater Bay, Somerset". The Journal of Ecology. 61 (2): 383–386. doi:10.2307/2259033. JSTOR 2259033.

- Twist, Colin, Rare Plants in Great Britain - a site guide

- Green, Ian, Peter Green and Geraldine Crouch The Atlas Flora of Somerset

- "Steart (part of Bridgwater Bay NNR)". Somerset Birding. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "August 30th 2016". Levels Birder. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- Cadwalladr, D.A.; Owen, Myrfyn; Morley, J.V.; Cook, R.S. (1972). "Wigeon (Anas penelope L.) Conservation and Salting Pasture Management at Bridgwater Bay National Nature Reserve, Somerset". Journal of Applied Ecology. 9 (2): 417. doi:10.2307/2402442. JSTOR 2402442.

- Owen, Myrfyn (April 2008). "The winter feeding ecology of Wigeon at Bridgwater Bay, Somerset". Ibis. 115 (2): 227–243. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1973.tb02639.x. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

- Prater, A.J. (2010). Estuary Birds of Britain and Ireland. A and C Black. pp. 187–190. ISBN 978-1-4081-3847-2.

- "Avocets breed on Somerset's coast". Somerset Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Steart Marshes". Somerset Birding. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Sunday 16 August – WWT Steart Marshes and NNR Bridgwater Bay". Bristol Birding. 16 August 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Bridgwater Bay" (PDF). Bird Watch. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "England Somerset". Fat Birder. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Wildlife to see in February 2016". Somerset Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- Tipling, David (2006). Where to Watch Birds in Britain and Ireland. New Holland Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84537-459-4.

- "Stolford and Hinkley Point". Somerset Birds. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "Species List". Brean Bird List. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Dunnock". Brean Bird List. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- Moss, Stephen (20 January 2013). "Birdwatch: Rock pipit". Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "What to see in July". Somerset Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- "Wet summer devastating Somerset's butterfly population, says Sir David Attenborough". Bridgwater Mercury. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bridgwater Bay. |