Wookey Hole Caves

Wookey Hole Caves (/ˈwʊki/) are a series of limestone caverns, a show cave and tourist attraction in the village of Wookey Hole on the southern edge of the Mendip Hills near Wells in Somerset, England. The River Axe flows through the cave.[2] It is a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for both biological and geological reasons.[3] Wookey Hole cave is a "solutional cave", one that is formed by a process of weathering in which the natural acid in groundwater dissolves the rocks. Some water originates as rain that flows into streams on impervious rocks on the plateau before sinking at the limestone boundary into cave systems such as Swildon's Hole, Eastwater Cavern and St Cuthbert's Swallet; the rest is rain that percolates directly through the limestone. The temperature in the caves is a constant 11 °C (52 °F).

| Wookey Hole Caves | |

|---|---|

The River Axe emerging from Wookey Hole Caves | |

| |

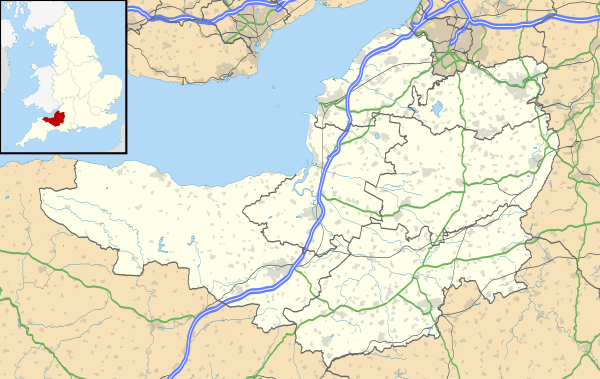

| Location | Wookey Hole, Somerset, UK |

| OS grid | ST 5319 4802 |

| Coordinates | 51.2293°N 2.6718°W[1] |

| Depth | 90 metres (300 ft)[1] |

| Length | 3,890 metres (12,760 ft)[1] |

| Height variation | 141 metres (463 ft)[1] |

| Elevation | 64 metres (210 ft)[1] |

| Geology | Dolomitic conglomerate and limestone |

| Entrances | 6 (incl. 1 artificial, 1 blocked) |

| Access | Restricted |

| Show cave opened | 1927 |

| Lighting | Electric |

| Registry | MCRA [1] |

The caves have been used by humans for around 45,000 years, demonstrated by the discovery of tools from the Palaeolithic period, along with fossilised animal remains. Evidence of Stone and Iron Age occupation continued into Roman Britain. A corn-grinding mill operated on the resurgent waters of the River Axe as early as the Domesday survey of 1086. The waters of the river are used in a handmade paper mill, the oldest extant in Britain, which began operations circa 1610.[4] The low, constant temperature of the caves means that they can be used for maturing Cheddar cheese.

The caves are the site of the first cave dives in Britain which were undertaken by Jack Sheppard and Graham Balcombe. Since the 1930s divers have explored the extensive network of chambers developing breathing apparatus and novel techniques in the process. The full extent of the cave system is still unknown with approximately 4,000 metres (13,000 ft), including 25 chambers, having been explored. Part of the cave system opened as a show cave in 1927 following exploratory work by Herbert E. Balch. As a tourist attraction it has been owned by Madame Tussauds and, most recently, the circus owner Gerry Cottle. The cave is notable for the Witch of Wookey Hole, a roughly human shaped stalagmite that legend says is a witch turned to stone by a monk from Glastonbury. It has also been used as a location for film and television productions, including the Doctor Who serial Revenge of the Cybermen.

Description

The show cave consists of a dry gallery connecting three large chambers, the first of which contains the Witch of Wookey formation. There are various high level passages leading off from these chambers, with two small exits above the tourist entrance. The River Axe is formed by the water entering the cave systems and flows through the third and first chambers, from which it flows to the resurgence, through two sumps 40 metres (130 ft) and 30 metres (98 ft) long, where it leaves the cave and enters the open air. [5][6]

The river is maintained at an artificially high level and falls a couple of metres when the sluice is lowered to allow access to the fourth and fifth chambers, two small air spaces. Normally, however, these are only accessible by cave diving. Beyond the fifth chamber a roomy submerged route may be followed for a further 40 metres (130 ft), passing under three large rifts with air spaces, to surface in the ninth chamber – a roomy chamber over 30 metres (98 ft) long and the same high. High level passages here lead to a former resurgence, now blocked, some 45 metres (148 ft) above the current resurgence.[5][6]

An artificial tunnel 180 metres (590 ft) leading off from the third chamber allows show cave visitors to cross the seventh and eighth chambers on bridges, and skirt around the ninth chamber on a walkway, before exiting near the resurgence.[5] A second excavated 74-metre-long (243 ft) tunnel from the ninth chamber allows visitors to visit the 20th chamber.[7][8]

From the ninth chamber, a dive of about 200 metres (660 ft) passes almost immediately from the Dolomitic Conglomerate into the limestone, and descends steadily for 70 metres (230 ft) to a depth of 23 metres (75 ft) under a couple of high rifts with airbells, which are enclosed air spaces between the water and the roof, before reaching air space in the 19th chamber. The 20th chamber is at the top of a large boulder slope – 60 metres (200 ft) long, 15 metres (49 ft) wide, and 22 metres (72 ft) high. From here a roomy passage some 400 metres (1,300 ft) long ascends towards a now-blocked fossil resurgence in the Ebbor Gorge. The total length of passages in this area is about 820 metres (2,690 ft).[5][6] A passage near the end is being cleared in an attempt to provide an easier connection with the 24th chamber, which is only an estimated 30 metres (98 ft) away.[9]

The continuation is found in the 19th chamber, where 152 metres (499 ft) of passage descending to a depth of 24 metres (79 ft) surfaces in the 22nd chamber – 300 metres (980 ft) of dry passages at various levels with a static pool. The way on is within this pool at a depth of 19 metres (62 ft) where 100 metres (330 ft) of passage ascends to surface in the 23rd chamber – 100 metres (330 ft) of large passage, followed by four short sumps that arrive in the 24th chamber. This is 370 metres (1,210 ft) of what is described in the guide book as "magnificent" river passage, 13 metres (43 ft) high and 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide, which finishes at a cascade falling from a 30 metres (98 ft) long lake. There are also more than 370 metres (1,210 ft) of high level passages above the river. The way on continues underwater for some 100 metres (330 ft) reaching a depth of 25 metres (82 ft) before surfacing in the 25th chamber – called the Lake of Gloom because of its thick mud deposits.[5][6] The sump at the end of this has been dived for 400 metres (1,300 ft) to a maximum depth of 90 metres (300 ft) before gravel chokes prevented further progress. The end is located about 1,000 metres (1,100 yd) northeast of the entrance.[1]

Hydrology and geology

Wookey Hole is on the southern escarpment of the Mendip Hills, and is the resurgence which drains the southern flanks of North Hill and Pen Hill. It is the second largest resurgence on Mendip, with an estimated catchment area of 46.2 square kilometres (17.8 sq mi),[10] and an average discharge of 789 litres (174 imp gal; 208 US gal) per second.[11] Some of the water is allogenic in origin i.e. drained off non-limestone rocks, collecting as streams on the surface before sinking at or near the Lower Limestone Shale — Black Rock Limestone boundary, often through swallets such as Plantation Swallet near St Cuthbert's lead works between the Hunter's Lodge Inn and Priddy Pools.[12] It then passes through major cave systems such as Swildon's Hole, Eastwater Cavern and St Cuthbert's Swallet, around Priddy,[13][14] but 95% is water that has percolated directly into the limestone.[14]

The southern slopes of the Mendip Hills largely follow the flanks of an anticline, a fold in the rock that is convex upwards and has its oldest beds at its core. On the Mendips the crest of the anticline is truncated by erosion, forming a plateau. The rock strata here dip 10–15 degrees to the southwest.[15] The outer slopes are mainly of Carboniferous Limestone, with Devonian age Old Red Sandstone exposed as an inlier at the centre. Wookey Hole is a solutional cave mainly formed in the limestone by chemical weathering whereby naturally acidic groundwater dissolves the carbonate rocks, but it is unique in that the first part of the cave is formed in Triassic Dolomitic Conglomerate, a well-cemented fossil limestone scree representing the infill of a Triassic valley.[16]

The cave was formed under phreatic conditions i.e. below the local water table, but lowering base levels to which the subterranean drainage was flowing resulted in some passages being abandoned by the river, and there is evidence of a number of abandoned resurgences.[15] In particular, the passages in the 20th chamber are interpreted as a former Vauclusian spring, the waters of which once surfaced in the Ebbor Gorge.[17] It is uncertain whether that was the original rising or whether it formed when the main rising at Wookey was blocked.[18]

The current resurgence is located close to the base of the Dolomitic Conglomerate at the head of a short gorge formed by headward erosion with subsequent cavern collapse.[19] The morphology of the passages is determined by the rock strata in which they are formed. The streamway in the outer part of the cave system that is formed within the Dolomitic Conglomerate is characterised by shallow loops linking low bedding chambers, or tall narrow passages, known as 'rifts', developed by phreatic solutional enlargement of fractured rifts. The streamway in the inner part of the system formed within the limestone is characterised by deep phreatic loops reaching depths as much as 90 metres (300 ft), with the water flowing down-dip along bedding planes and rising up enlarged joints.[19] In the far reaches of the cave the passages descend to 26 metres (85 ft) below sea level.[1][2]

History

Witcombe suggests that the name Wookey is derived from the Celtic (Welsh) for 'cave', "Ogo" or "Ogof" which gave the early names for this cave of "Ochie" "Ochy". Hole is Anglo-Saxon for cave, which is itself of Latin/Norman derivation. Therefore, the name Wookey Hole Cave basically means cave cave cave.[20] Eilert Ekwall gives an alternative derivation of Wookey from the Old English "wocig" meaning a noose or snare for animals.[21] By the 18th century the caves were commonly known as "Okey Hole".[22] It was known as such when it was first described in print in 1681 by the geologist John Beaumont.[23]

Fossils of a range of animals have been found including the Pleistocene lion (Felis leo spelæ), Cave hyena (Crocuta crocuta spelaea) and Badger (Meles meles).[24] Wookey Hole was occupied by humans in the Iron Age, possibly around 250-300 BC,[25] while nearby Hyena Cave was occupied by Stone Age hunters. Badger Hole and Rhinoceros Hole are two dry caves on the slopes above the Wookey ravine near the Wookey Hole resurgence and contain in situ cave sediments laid down during the Ice Age.[3] Just outside the cave the foundations of a 1st-century hut have been identified. These had been built on during the Roman era up to the end of the 4th century.[26]

In 1544 products of Roman lead working in the area were discovered. The lead mines across the Mendips have produced contamination of the water emerging from the caverns at Wookey Hole.[27] The lead in the water is believed to have affected the quality of the paper produced.[28]

The designation of the water catchment area for Wookey Hole, covering a large area of the Mendip Hills as far away as Priddy Pools as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) during the 1970s and 1980s was controversial because of conflicts of interest between land owners, recreational cavers and cave scientists.[29] Initially proposals were put forward by the Council of Southern Caving Clubs which is part of the British Caving Association was that SSSI designation, which would restrict what farmers and other landowners were allowed to do, would cover the entire catchment area. This was opposed as being too restrictive and difficult to enforce. It was argued that agricultural uses of fields which were not directly in contact with cave entrances would have little detrimental effect on the caves themselves. There was also debate about which caves and cave features should be considered "important". The final settlement resulted in a smaller area being designated and many agricultural practices being removed from the list of proscribed "Potentially Damaging Operations".[29]

The entrance weir and sluice gate servicing the paper mill was built about 1852. The tunnel excavated from the third chamber to the ninth chamber and then out to daylight was dug in 1974–1975 by ex-coal miners from the Radstock area.[1] The show cave was further extended in 2015 by excavating a tunnel from the ninth chamber to the 20th chamber.[7]

The constant temperature of 11 °C (52 °F) in the caves is used by Ford Farm of Dorset to mature Cheddar cheese in the 'Cheese Tunnel' – an excavated side tunnel between the ninth chamber and the exit to the show cave.[30][31]

Cave archaeology

Archaeological investigations were undertaken from 1859 to 1874 by William Boyd Dawkins, who moved to Somerset to study classics with the vicar of Wookey. On hearing of the discovery of bones by local workmen he led excavations in the area of the hyena den. His work led to the discovery of the first evidence for the use by Paleolithic humans in the Caves of the Mendip Hills.[32] Middle Paleolithic tools have been found in association with butchered bones with a radiocarbon age of around 41,000 years.[33]

Herbert E. Balch continued the work from 1904 to 1914,[34] when he led excavations of the entrance passage (1904–1915), Witch's Kitchen (the first chamber) and Hell's Ladder (1926–1927) and the Badger Hole (1938–1954), where Roman coins from the 3rd century were discovered along with Aurignacian flint implements.[35] Rhinoceros Hole was scheduled as an ancient monument in 1992.[36] The 1911 work found 4 to 7 feet (1.2–2.1 m) of stratification, mostly dating from the Iron Age and sealed into place by Romano-British artefacts. Finds included a silver coin of Marcia (124 BC), pottery, weapons and tools, bronze ornaments, and Roman coins from Vespasian to Valentinian II[37] (1st to 4th centuries).

The work was continued, first by E. J. Mason from 1946 to 1949, and then by G. R. Morgan in 1972.[38] Later work led by Edgar Kingsley Tratman explored the human occupation of the Rhinoceros hole,[39] and showed that the fourth chamber of the great cave was a Romano-British cemetery.[40][41] During excavations in 1954–1957 at Hole Ground, just outside the entrance to the cave, the foundations of a 1st-century hut and Iron Age pottery were seen. These were covered by the foundations of Roman buildings, dating from the 1st to the late 4th century.[42]

Exploration

The cave as far as the third chamber and side galleries has been known since at least the Iron Age period.[6] Prior to the construction of a dam at the resurgence to feed water to the paper mill downstream, two more chambers (the Fourth and Fifth) were accessible. Further upstream the way lies underwater. Diving was first tried by the Cave Diving Group under the leadership of Graham Balcombe in 1935. With equipment on loan from Siebe Gorman, he and Penelope ("Mossy") Powell penetrated 52 m (170 ft) into the cave, reaching the seventh chamber, using standard diving dress. The events marked the first successful cave dives in Britain.[43][44]

Diving at Wookey resumed in early June 1946 when Balcombe used his homemade respirator and waterproof suit to explore the region between the resurgence and first chamber, as well as the underground course of the river between the third and first chambers. During these dives, the Romano-British remains were found and archaeological work dominated the early dives in the cave. The large ninth chamber was first entered on 24 April 1948 by Balcombe and Don Coase. Using this as an advance dive base, the 10th and then 11th chambers were discovered. The way on, however, was too deep for divers breathing pure oxygen from a closed-circuit rebreather. The cave claimed its first life on 9 April 1949 when Gordon Marriott lost his life returning from the ninth chamber.[45][46] Another fatality was to occur in 1981 when Keith Potter was drowned on a routine dive further upstream.[47][48]

Further progress required apparatus which could overcome the depth limitation of breathing pure oxygen. In 1955 using an aqualung and swimming with fins, Bob Davies reached the bottom of the 11th chamber at 15 m (49 ft) depth in clear water and discovered the 12th and 13th chambers. He got separated from his guideline and the other two divers in the 11th chamber, ending up spending three hours trapped in the 13th chamber and had much trouble getting back to safety.[49] Opinion hardened against the use of the short-duration aqualung in favour of longer-duration closed-circuit equipment. Likewise, the traditional approach of walking along the bottom was preferred over swimming. Employing semi-closed circuit nitrogen-oxygen rebreathers, between 1957 and 1960 John Buxton and Oliver Wells went on to reach the elbow of the sump upstream from the ninth chamber at a depth of 22 m (72 ft).[50] This was at a point known as "The Slot", the way on being too deep for the gas mixture they were breathing.

A six-year hiatus ensued while open circuit air diving became established, along with free-swimming and the use of neoprene wetsuits. The new generation of cave diver was now more mobile above and under water and able to dive deeper. Using this approach, Dave Savage was able to reach air surface in the 18th chamber (chambers did not have to have air spaces to be so named; they were the limits of each exploration) in May 1966. A brief lull in exploration occurred while the mess of guidelines laid from the ninth chamber was sorted out before John Parker progressed first to the large, dry, inlet passage of the 20th chamber, and thence followed the River Axe upstream on a dive covering 152 metres (499 ft) at a maximum depth of 24 metres (79 ft) to the 22nd chamber where the way on appeared to be lost.[51][52]

Meanwhile, climbing operations in the ninth chamber found an abandoned outlet passage which terminated very close to the surface, as well as a dry overland route downstream through the higher levels of the eighth, seventh and sixth chambers as far as the fifth chamber. These discoveries were used to enable the show cave to be extended into the ninth chamber and the cave divers to start directly from here, bypassing the dive from the third chamber onwards.[53] The way on from the 22nd chamber was at last found by Colin Edmond and Martyn Farr in February 1976 and was explored until the line ran out. A few days later Geoff Yeadon and Oliver Statham somewhat controversially reached the 23rd chamber after laying just a further 9 metres (30 ft) of line. A further three short dives and they surfaced in the 24th chamber to be confronted by what Statham described as "a magnificent sight—the whole of the River Axe pouring down a passage 40 feet [12 m] high by five feet [1.5 m] wide" terminating in a blue lake after 90 metres (300 ft). This lake was dived by Farr a few days later for 90 metres (300 ft) at a maximum depth of 18 metres (59 ft) to emerge in the 25th chamber, a desolate, muddy place named "The Lake of Gloom".[54]

The 25th chamber represents the furthest upstream air surface in Wookey Hole Cave. From here the River Axe rises up from a deep sump where progressive depth records for cave diving in the British Isles have been set: firstly by Farr (45 m or 148 ft) in 1977, then Rob Parker (68 m or 223 ft) in 1985, and finally by John Volanthen and Rick Stanton (76 m or 249 ft) in 2004.[55][56] The pair returned again in 2005 to explore the sump to a depth of 90 m (300 ft), setting a new British Isles depth record for cave diving.[52] This record was broken in 2008 by Polish explorer Artur Kozłowski, then later again by Michal Marek, on dives in Pollatoomary in Ireland.[57][58]

During 1996–1997 water samples were collected at various points throughout the caves and showed different chemical compositions. Results showed that the location of the "Unknown Junction", from where water flows to the static sump in the 22nd chamber by a different route from the majority of the River Axe, is upstream of the sump in the 25th.[59]

Witch of Wookey Hole

There are old legends of a "witch of Wookey Hole", which are still preserved in the name of a stalagmite in the first chamber of the caves. The story has several different versions with the same basic features:

A man from Glastonbury is engaged to a young woman from Wookey. A witch living in Wookey Hole Caves curses the romance so that it fails. The man, now a monk, seeks revenge on this witch who—having been jilted herself—frequently spoils budding relationships. The monk stalks the witch into the cave and she hides in a dark corner near one of the underground rivers. The monk blesses the water and splashes some of it at the dark parts of the cave where the witch was hiding. The blessed water immediately petrifies the witch, and she remains in the cave to this day.[60][61]

A 1000-year-old skeleton was discovered in the caves by Balch in 1912, and has also traditionally been linked to the legendary witch, although analysis indicated that they are the remains of a male aged between 25-35.[62] The remains have been part of the collection of the Wells and Mendip Museum, which was founded by Balch, since they were excavated, though in 2004 the owner of the caves said that he wanted them to be returned to Wookey Hole.[63]

It was partly the legend of the witch that prompted TV's Most Haunted team to visit Wookey Hole Caves and Mill to explore the location in depth, searching for evidence of paranormal activity. The show, which aired on 10 March 2009, was the last episode transmitted in series 11 of the show's run on the satellite and cable TV channel Living.[64] In 2009, a new actor to play the 'witch' was chosen by Wookey Hole Ltd amid much media interest. Carole Bohanan in the role of Carla Calamity was selected from over 3,000 applicants.[65]

Tourism

The cave was first opened to the public by the owner Captain G.W. Hodgkinson in 1927 following preparatory work by Balch.[66] Three years later, John Cowper Powys wrote of the caves in the novel A Glastonbury Romance.[67] Hodgkinson took offence at the portrayal of his fictional equivalent, initiating a costly libel suit.[68]

The current paper mill building, whose water wheel is powered by a small canal from the river, dates from around 1860 and is a Grade II listed building.[69] The commercial production of handmade paper ceased in February 2008 after owner Gerry Cottle concluded there was no longer a market for the product, and therefore sold most of the historic machinery. Visitors to the site are still able to watch a short video of the paper being made from cotton. Other attractions include the dinosaur valley, a small museum about the cave and cave diving, a theatre with circus shows, a house of mirrors and penny arcades.

In 1956, Olive Hodgkinson, a cave guide whose husband's family owned the caves for over 500 years, was a contestant on What's My Line?[70]

In the late 1950s, the caves were photographed by Stanley Long of VistaScreen, to be sold as both souvenirs and as mail-order stereoviews.[71]

The cave and mill were joined, after purchase, by Madame Tussauds in 1973 and operated together as a tourist attraction until there was a management team buyout in 1989.[72][73] A collection of fairground art of Wookey Hole was sold in 1997 at Christie's.[74][75] The present owner is the former circus proprietor Gerry Cottle,[76] who has introduced a circus school.[77]

The cave was used for the filming of episodes of the BBC TV series Doctor Who: the serial Revenge of the Cybermen (1975) starring Tom Baker.[78][79] This has since been referenced in the comedy of The League of Gentlemen. The cave was also used in the filming of the British series Blake's 7 (1978) and Robin of Sherwood (1983).[80][81] The caves were used again for Doctor Who in "The End of Time" (2009),[82] including a scene with the Doctor sharing thoughts and visions with the Ood.

On 1 August 2006, CNN reported that Barney, a Doberman Pinscher employed as a security dog at Wookey Hole, had destroyed parts of a valuable collection of teddy bears, including one which had belonged to Elvis Presley, which was estimated to be worth £40,000 (US$75,000). The insurance company insuring the exhibition of stuffed animals had insisted on having guard dog protection.[83] The incident was in fact one of a number of publicity stunts which included a cave guide being locked in the caves overnight, and the disappearance of a visiting Dalek during a Dr Who event.[84]

In February 2009 Cottle turned the Victorian bowling green next to the caves into a crazy golf course without first obtaining planning permission.[85]

References

- Gray, Alan; Taviner, Rob; Witcombe, Richard (2013). Mendip Underground, A Caver's Guide (Fifth ed.). Mendip Cave Registry and Archives. pp. 460–469. ISBN 978-0-9531310-5-1.

- "Wookey Hole and Ebbor Gorge". British Geological Survey. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Wookey Hole" (PDF). SSSI citation. English Nature. Retrieved 20 November 2008.

- "Hand-made Paper Mill". Wookey Hole Caves. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Irwin 1977, p. 162.

- Barrington & Stanton 1977, p. 179.

- W, Bayley. "PICTURES: Rare rock formation revealed at Wookey Hole Caves". Western Morning News. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Price, Duncan (October–December 2015). "Operation Twenty". Descent (246): 24–26.

- Bolt, Pete (February–March 2016). "Wookey 20 Dig". Descent (248): 9.

- Drew 1975, p. 200.

- Drew 1975, p. 191.

- "River Axe's main source discovered through mining". Weston, Worle & Somerset Mercury. 2 November 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- Waltham 1997, p. 199.

- Drew 1975, p. 209.

- Waltham 1997, p. 203.

- Waltham 1997, pp. 203–205.

- Waltham 1997, p. 205.

- Smith 1975, pp. 285-290.

- Waltham 1997, p. 204.

- Witcombe 2009, p. 202.

- Ekwall 1964, p. 532.

- Martin, Benjamin (1759). The Natural History of England: or, A Description of each Particular County, in Regard to the Curious Productions of Nature and Art. W. Owen. p. 63.

- The Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society of London 1685-1800. London: C. and R. Baldwin. 1809. pp. 487–488. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- Page 1906.

- Smith 1975, p. 381.

- "Prehistoric and Roman occupation, Hole Ground, Wookey Hole". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Macklin 1985, pp. 235–244.

- Gough 1967.

- Gunn & Gunn 1996, pp. 121–127.

- "Cave-aged cheese". Wookey Hole Caves. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- "Wookey Hole Cave Aged Cheddar wins awards for Dorset based Ford Farm". Blackmore Vale Magazine. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- Ramsay 1878, p. 474.

- Jacobi, Roger. "The Late Pleistocene archaeology of Somerset" (PDF). Somerset Heritage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "A Potted History of H. E. Balch 1869–1958". Bristol Exploration Club. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- "Badger Hole cave, Wookey Hole". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- Historic England. "Rhinoceros Hole, Wookey (1010292)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- "Wookey Hole Cave, Wookey Hole". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- "Hyena Cave, Wookey Hole". Hominid bearing caves in the south west. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- White & Pettitt 2011, pp. 25–97.

- Hawkes, Rogers & Tratman 1979, pp. 23–52.

- Proctor et al. 1996, pp. 237–262.

- "Prehistoric and Roman occupation, Hole Ground, Wookey Hole". Somerset Historic Environment Record. Somerset County Council. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- "UK Caves Database". Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- Buxton, John S. "The Cave Diving Group". CDG. Retrieved 28 September 2008.

- Farr, Martyn. "60 years in a cave". Divernet. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "A Century of British Caving". Craven Pothole Club. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Rose, Dave. "Keith Potter". Proceedings 10 : "Pozu del Xitu". Oxford University Cave Club. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Cave Rescues and Incidents for the Year ending 31 December. 1981". Belfry Bulletin. 410/411. June–July 1982.

- "CDG History 1950–1959". Cave Diving Group. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Farr 1991, p. 75.

- Farr 1991, p. 98.

- Hanwell, Price & Witcombe 2010.

- "Cathedral Cave". Wookey Hole Caves. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- Farr 1991, pp. 103–106.

- "Divers head for new depth record". BBC. 30 September 2004. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- "Rick Stanton". Diver Net. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- Gallagher, Emer (16 July 2008). "Explorer plunges to new depths in Mayo". The Mayo News. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Polak zginął podczas nurkowania w Irlandii". wbi.onet.pl (in Polish). 16 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2019.

- Chapman et al. 1999, pp. 107–113.

- Leete-Hodge 1985, p. 25.

- "The Wookey Hole Witch". This is Bristol. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- "Somerset Historic Environment Record, Wookey Hole Cave". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "Row breaks out over cave bones". BBC News. 5 June 2004. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Wookey Hole". Most Haunted. TV.com. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "New Witch for Wookey Hole". Witchology.com. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- Balch 1928, pp. 193–210.

- Rands 1992–1993, p. 49.

- Smith 1981–1982, p. 18.

- "Wookey Hole Paper Mill". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- "What's My Line? Season 8 Episode 12". TV.com. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- Ference, Ian (4 December 2018). "Series: Wookey Hole Caves". Brooklyn Stereography. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- Scott, Andy (2 February 2006). "Historic mill revamps its handmade grades". Print Week. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Chronology" (PDF). Madam Tussauds. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- Wolf, Matt (5 October 1997). "A Folk Art Menagerie Of Carnival Castoffs". New York Times. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- Moyes, Jojo (6 October 1997). "Roll up to buy artistic fairground attractions". Independent. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- "Wookey Hole Caves". British Attractions. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- "Turbo-charged entertainment for lovers of circus". Western Daily Press. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- "Doctor Who Fact File". BBC. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- "Doctor Who in Somerset". Art, Films and Television. BBC. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- "Most Popular Titles With Location Matching "Wookey Hole Caves, Wookey Hole, Somerset, England, UK"". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- "Wookey Hole Caves, Somerset". Robin of Sherwood. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Police called as caves witness end of time for tenth Doctor". This is Somerset. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Elvis' teddy bear leaves building the hard way: Guard dog rips head off Presley's $75,000 toy in stuffed-animal rampage". Associated Press. 3 August 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2007.

'He just went berserk', said Daniel Medley, general manager of Wookey Hole Caves near Wells, England, where hundreds of bears were chewed up Tuesday night by the six-year-old Doberman Pinscher named Barney. A security guard at the museum, Greg West, said he spent several minutes chasing Barney before wrestling the dog to the ground.

- "Missing Dr Who Dalek found on Tor". BBC. 14 June 2005. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "Pirate ship sails into Wookey Hole Caves crazy golf row". Bristol Evening Post. This is Bristol. 13 February 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

Bibliography

- Balch, Herbert E. (1947). Mendip — Its Swallet Caves and Rock Shelters. Bristol: Wright.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balch, Herbert E. (1913). "Further excavations at the late-Celtic and Romano-British cave-dwelling at Wookey Hole, Somerset". Archaeologia. 64: 337–346. doi:10.1017/S0261340900010766.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balch, Herbert E. (April 1928). "Excavations at Wookey Hole and other Mendip Caves, 1926–7". The Antiquaries Journal. 8 (2): 193–210. doi:10.1017/S0003581500012087.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Balch, Herbert E.; Troup, R.D.R. (January 1911). "A Late-Celtic and Romano-British Cave-dwelling at Wookey-Hole, near Wells, Somerset". Archaeologia. Second Series. 62 (2): 565–592. doi:10.1017/S0261340900008316.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barrington, Nicholas; Stanton, William (1977). Mendip: The Complete Caves and a View of the Hills. Cheddar: Cheddar Valley Press. ISBN 978-0-9501459-2-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bell, Alan (1928). Wookey Hole: The cave & its history. A description and history of the three great caverns, their ancient occupation and the legend of the witch of Wookey. G. W. Hodgkinson.

- Branigan, K.; Dearne, M.J. (1990). "The Romano-British finds from Wookey Hole: a re-appraisal". Proceedings of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society. 134: 57–80.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Branigan, K.; Dearne, M.J. (1991). A gazetteer of Romano-British cave sites and their finds. University of Sheffield. hdl:10068/419751. ISBN 978-0-906090-40-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, T.A.; Gee, A.V.; Knights, C.; Stell; Stenner, R.D. (1999). "Water studies in Wookey Hole Cave, Somerset, UK". Cave and Karst Science. 26 (3): 107–113.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawkins, W.B. (1862) On a hyaena den at Wookey Hole, near Wells. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 18: 115–126.

- Dawkins, W.Boyd (1863). "On a hyaena den at Wookey Hole, near Wells". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 19 (1–2): 260–274. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1863.019.01-02.27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawkins, W.Boyd (1874). Cave Hunting, Researches in the Evidence of Caves Respecting the Early Inhabitants of Europe. MacMillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drew, Dave (1975). D.I. Smith (ed.). Limestone and Caves of the Mendip Hills. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-6572-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ekwall, Eilert (1964). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farr, Martyn (1991). The Darkness Beckons. London: Diadem Books. ISBN 978-0-939748-32-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Faulkner, T.J. (1989). "The early Carboniferous (Courceyan) Middle Hope volcanics of Weston-super-Mare: development and demise of an offshore volcanic high". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. The Geologists' Association Published by Elsevier Ltd. 100 (1): 93–106. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(89)80068-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gough, J.W. (1967). The mines of Mendip. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gunn, J.; Gunn, P. (1996). "The conservation of Britain's limestone cave resource" (PDF). Environmental Geology. 28 (3): 121–127. Bibcode:1996EnGeo..28..121H. doi:10.1007/s002540050084.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanwell, J.D; Price, D.M.; Witcombe, R.G. (2010). Wookey Hole – 75 years of cave diving and exploration. Wells: Cave Diving Group. ISBN 978-0-901031-07-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haslett, Simon K. (2010). Somerset Landscapes: Geology and landforms. Usk: Blackbarn Books. ISBN 978-1-4564-1631-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkes, C.F.C. (1950). "Wookey Hole" (PDF). The Archaeological Journal. 107: 92–93.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hawkes, C.J.; Rogers, J.M.; Tratman, E.K. (1979). "Romano-British cemetery in the fourth chamber of Wookey Hole Cave, Somerset". Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 15: 23–52.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Irwin, Dave (1977). Mendip Underground. A Caver's Guide. Wells: Mendip Publishing. ISBN 978-0-905903-08-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobi, R.M.; Hawkes, C.J. (1993). "Archaeological notes: work at the Hyaena Den, Wookey Hole" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 19 (3): 369–371.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kellaway, G. A.; Welch, F. B. A. (1948). Bristol and Gloucester District. British Regional Geology (Second ed.). London: HMSO for Natural Environment Research Council, Institute of Geological Sciences, Geographical Survey and Museum. ISBN 978-0-11-880064-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leete-Hodge, Lornie (1985). Curiosities of Somerset. Bodmin: Bossiney Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-906456-98-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macklin, Mark G. (1985). "Flood-Plain Sedimentation in the Upper Axe Valley, Mendip, England". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 10 (2): 235–244. doi:10.2307/621826. JSTOR 621826.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, E.J. (1950). "Note on recent exploration in Wookey Hole" (PDF). The Archaeological Journal. 107: 93–94.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, E.J. (1951). "Report of human remains and materials recovered from the River Axe in the Great Cave of Wookey Hole during diving operations from October 1947 to Jan. 1949". Transactions of the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society. 96: 238–243.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McBurney, C.B.M. (1961). "Two soundings in the Badger Hole near Wookey Hole in 1958 and their bearing on the Palaeolithic finds of the late H.E. Balch". Mendip Nature Research Committee Report. 50/51: 19–27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McComb, Patricia (1989). Upper Palaeolithic Osseous Artifacts from Britain and Belgium: An Inventory and Technological Description. British Archaeological Reports International Series. ISBN 978-0-86054-618-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Page, William (1906). "Palaeontology". A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 1. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 9 December 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Proctor, C.J.; Collcutt, S.N.; Currant, A.P.; Hawkes, C.J.; Roe, D.A.; Smart, P.L. (1996). "A report on the excavations at Rhinoceros Hole, Wookey" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 20 (3): 237–262.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ramsay, A.C. (1878). "28 Newer pliocene epoch, continued — Bone Caves, and traces of man". The physical geology and geography of Great Britain. London: Edward Stanford. p. 474.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rands, Susan (1992–1993). "The Topicality of A Glastonbury Romance". The Powys Review. 27-28: 42–53.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaw, T.R. (1996). "Why some caves become famous — Wookey Hole, England". Cave and Karst Science. 23 (1): 17–23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, David Ingle (1975). Limestone and Caves of the Mendip Hills. David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-6572-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Penny (1981–1982). "The 'cave of the man-eating Mothers': Its Location in A Glastonbury Romance". The Powys Review. 9: 10–37.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stack, M.V.; Coles, S.G. (1983). "Concentrations of lead, cadmium, copper and zinc in teeth from a cave used for Romano-British burials: effect of lead contamination" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 16 (3): 193–200.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tratman, E.K.; Donovan, D.T.; Campbell, J.B. (1971). "The Hyaena Den (Wookey Hole), Mendip Hills, Somerset" (PDF). Proceedings of the University of Bristol Speleological Society. 12 (3): 245–279.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tratman, E.K. (1975). "The cave archaeology and palaeontology of Mendip". In Smith, D.I.; Drew, D.P. (eds.). Limestones and Caves of the Mendip Hills. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-6572-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Waltham, A.C. (1997). Karst and Caves of Great Britain. Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-78860-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, M.J.; Pettitt, P.B. (2011). "The British Late Middle Palaeolithic : an interpretative synthesis of Neanderthal occupation at the northwestern edge of the pleistocene world" (PDF). Journal of World Prehistory. 24 (1): 25–97. doi:10.1007/s10963-011-9043-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Witcombe, Richard (2009). Who was Aveline anyway?: Mendip's Cave Names Explained (2nd ed.). Priddy: Wessex Cave Club. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-905903-31-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wookey Hole Caves. |