Radstock

Radstock is a town in Somerset, England, 9 miles (14 km) south west of Bath, and 8 miles (13 km) north west of Frome. It is within the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset and had a population of 5,620 according to the 2011 Census.[1] Since 2011 Radstock has been a town council in its own right.

| Radstock | |

|---|---|

The old winding wheel on a headframe, now in the centre of Radstock, in front of the Radstock Museum | |

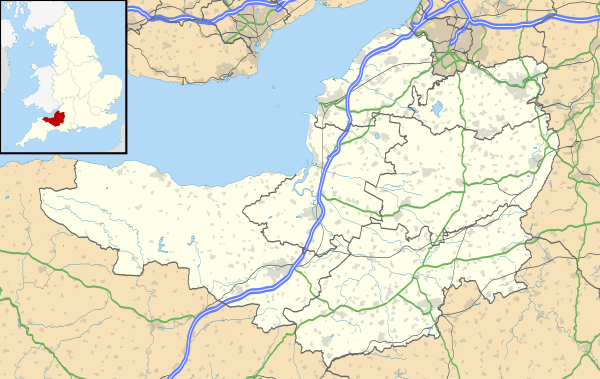

Radstock Location within Somerset | |

| Population | 5,620 (2011 Census[1] |

| OS grid reference | ST688549 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | RADSTOCK |

| Postcode district | BA3 |

| Dialling code | 01761 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Radstock has been settled since the Iron Age, and its importance grew after the construction of the Fosse Way, a Roman road. The growth of the town occurred after 1763, when coal was discovered in the area. Large numbers of mines opened during the 19th century including several owned by the Waldegrave family, who had been Lords of the Manor since the English Civil War. Admiral Lord Radstock, brother of George, fourth Earl Waldegrave, took the town's name as his title when created a Baron.

The spoil heap of Writhlington colliery is now the Writhlington Site of Special Scientific Interest, which includes 3,000 tons of Upper Carboniferous spoil from which more than 1,400 insect fossil specimens have been recovered. The complex geology and narrow seams made coal extraction difficult. Tonnage increased throughout the 19th century, reaching a peak around 1901, when there were 79 separate collieries and annual production was 1,250,000 tons per annum. However, due to local geological difficulties and manpower shortages output declined and the number of pits reduced from 30 at the beginning of the 20th century to 14 by the mid-thirties; the last two pits, Kilmersdon and Writhlington, closed in September 1973. The Great Western Railway and the Somerset and Dorset Railway both established stations and marshalling yards in the town. The last passenger train services to Radstock closed in 1966. Manufacturing industries such as printing, binding and packaging provide some local employment. In recent years, Radstock has increasingly become a commuter town for the nearby cities of Bath and Bristol.

Radstock is home to the Radstock Museum which is housed in a former market hall, and has a range of exhibits which offer an insight into north-east Somerset life since the 19th century. Many of the exhibits relate to local geology and the now disused Somerset coalfield and geology. The town is also home to Writhlington School, famous for its Orchid collection, and a range of educational, religious and cultural buildings and sporting clubs.

History

Radstock has been settled since the Iron Age.[2] Its importance grew with the construction of the Fosse Way, the Roman road that ran along what is now part of the A367 in Radstock. As a result, the town was known as Stoche at the time of the Domesday Book of 1086, meaning the stockade by the Roman road, from the Old English stoc.[3] The rad part of the name is believed to relate to red; the soil locally is reddish marl.[4] The parish of Radstock was part of the Kilmersdon Hundred,[5]

The Great Western Railway, and the Somerset and Dorset Railway, established stations and marshalling yards in the town. Radstock was the terminus for the southern branch of the Somerset Coal Canal, which was turned into a tramway in 1815.[6] It then became a central point for railway development, with large coal depots, wash houses, workshops and a gas works. As part of the development of the Wiltshire, Somerset and Weymouth Railway, an 8-mile (13 km) line from Radstock to Frome was built to carry the coal. In the 1870s the broad-gauge line was converted to standard gauge and connected to the Bristol and North Somerset Line which linked the town to the Great Western Railway. The Radstock Railway Land covers the old marshalling yards and sheds and comprises an area of approximately 8.8 hectares of land which is the subject of ongoing planning and development applications to redevelop the area.[7][8]

The town is close to the site of the Radstock rail accident, a rail crash that took place on the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway, on 7 August 1876. Two trains collided on a single track section, resulting in the deaths of 15 passengers.[9]

The last passenger train services in Radstock closed in 1966, and the last coal mines closed in 1973. Manufacturing industries such as printing, binding and packaging provide some local employment. More recently Radstock has become a commuter town for the nearby cities of Bath and Bristol, leading to traffic problems at peak hours.[10]

Coal mining

In 1763, coal was discovered in Radstock and mining began in the area.[11] In, 1896 the pits were owned by the Trustee of Frances, late Countess of Waldegrave.[12] The Waldegrave family had been Lords of the Manor of Radstock since the English Civil War. Between 1800 and 1850, Ludlows, Middle Pit, Old Pit, Smallcombe, Tynings, and Wellsway mines opened. There were also a series of pits east of the town at Writhlington and under different ownership. In 1896, they were owned by Writhlington, Huish and Foxcote Colliery Co.;[12] however, following an acrimonious dispute about the terms and conditions of the miners in 1899,[13] a new company, Writhlington Collieries Co., was set up to run the mines.[14] The Upper and Lower Writhlington, Huish and Foxcote were all merged into one colliery. The spoil heap is a now Writhlington Site of Special Scientific Interest. The site and includes 3,000 tons of Upper Carboniferous spoil from which more than 1,400 insect fossils have been recovered.[15] These include Phalangiotarbi,[16] and Graeophonus.[17] and the world's earliest known Damselfly.[18] It is a Geological Conservation Review Site.[19]

The complex geology and narrow seams made the coal extraction difficult; three underground explosions, in 1893, 1895 and 1908, were amongst the first attributable solely to airborne coal dust.[20]

Tonnage increased throughout the 19th century, reaching a peak around 1901, when there were 79 separate collieries and annual production was 1.25 million tons per annum.[21] However, due to local geological difficulties and manpower shortages,[22] decline soon took hold and the number of pits reduced from 30 at the beginning of the 20th century to 14 by the mid-thirties, 12 at nationalisation to create National Coal Board on 1 January 1947, 5 by 1959 and none after 1973.[23] Narrow seams made production expensive, limiting profit and investment, and a reduced national demand together with competition from more economical coalfields led to the closure of the last two pits in the coalfield, Kilmersdon and Writhlington, in September 1973.[23]

Governance

As of 2011, Radstock became a town council in its own right. Until then, the town was part of the Norton Radstock civil parish, which was created in 1974 as a successor to the Norton-Radstock Urban District, itself created in 1933 by the merger of Midsomer Norton and Radstock urban districts, along with part of Frome Rural District.[24] Under the Local Government Act 1972 it became a successor parish to the urban district.

Radstock is governed by the unitary authority of Bath and North East Somerset and by Radstock Town Council. There is one electoral ward in Radstock with the same area and population as is quoted above.

It was also part of the Wansdyke constituency, which elects a Member of Parliament to the House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. At the 2010 general election this constituency changed to North East Somerset.[25] It is also part of the South West England constituency of the European Parliament.

Geography

The main geological feature in this area of the Mendip Hills south of Hallatrow consists of Supra-Pennant Measures which includes the upper coal measures and outcrops of sandstone.[26] The southern part of the Radstock Syncline have coals of the Lower and Middle Coal Measures been worked, mainly at the Newbury and Vobster collieries in the southeast and in the New Rock and Moorewood pits to the southwest.[27] The Hercynian orogeny caused shock waves in the rock as the Mendip Hills were pushed up, forcing the coal measures to break along fractures or faults. Along the Radstock Slide Fault the distance between the broken ends of a coal seam can be as much as 1,500 feet (457 m).[28]

Radstock lies on the Wellow Brook which then runs through Wellow to join the Cam Brook at Midford to form Midford Brook before joining the River Avon close to the Dundas Aqueduct and the remains of the Somerset Coal Canal. The base of the valley is of alluvium deposits. Above this on both sides of all of the valley is a band of shales and clays from the Penarth Group. These rocks are from the Triassic period. The majority of the remaining upland around Radstock is Lias Limestone (white and blue) while the very highest part above 130 m, south of Haydon, is a small outcrop of Inferior Oolitic Limestone. All these limestones are from the Jurassic period. The steepest slopes of both the Kilmersdon and Snail’s Bottom valleys have frequently slipped. Below all of the area is the coal bearing Carboniferous strata. Haydon is an outlier of Radstock and was built to house the miners for the local pit. The disused railway line and inclined railway at Haydon form important elements within the Kilmersdon valley east of Haydon. The modern landscape has a less maintained and "rougher" character and texture than neighbouring agricultural areas. This is caused in the main by the remnants of the coal industry and its infrastructure and changes in agricultural management. The disturbance caused by coal mining and the railways and the subsequent ending of mining and disuse of the railways has created valuable habitats of nature conservation interest.[29]

Along with the rest of South West England, Radstock has a temperate climate, which is generally wetter and milder than the rest of England. The annual mean temperature is about 10 °C (50 °F) with seasonal and diurnal variations, but because of the modifying effect of the sea, the range is less than in most other parts of the United Kingdom. January is the coldest month, with mean minimum temperatures between 1 °C (34 °F) and 2 °C (36 °F). July and August are the warmest months in the region, with mean daily maxima around 21 °C (70 °F). In general, December is the dullest month and June the sunniest. The southwest of England enjoys a favoured location, particularly in summer, when the Azores High extends its influence north-eastwards towards the UK.[30]

Cloud often forms inland, especially near hills, and reduces exposure to sunshine. The average annual sunshine is about 1,600 hours. Rainfall tends to be associated with Atlantic depressions or with convection. In summer, convection caused by solar surface heating sometimes forms shower clouds, and a large proportion of the annual precipitation falls from showers and thunderstorms at that time of year. Average rainfall is 800–900 mm (31–35 in). About 8–15 days of snowfall is typical. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, and June to August having the lightest. The predominant wind direction is from the southwest.[30]

Transport

Radstock was the terminus for the southern branch of the Somerset Coal Canal, which was turned into a tramway in 1815 and later incorporated into the Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway.[6] It then became a central point for railway development with large coal depots, warehouses, workshops and a gas works. As part of the development of the Wilts, Somerset and Weymouth Railway an 8-mile (13 km) line from Radstock to Frome was built to carry the coal. In the 1870s the broad-gauge line was converted to standard gauge and connected to the Bristol and North Somerset Line connecting it to the Great Western Railway at Bristol; the GWR also took over the Wiltshire, Somerset and Weymouth Railway in 1876. The Bristol and North Somerset line closed to passenger traffic in 1959. The line is now the route of National Cycle Route 24, otherwise known as the Colliers' Way, a national cycle route which passes many landmarks associated with the coal field;[31] other local roads and footpaths follow the tramways developed during the coal mining years.[32] The cycle route currently runs from Dundas Aqueduct to Frome via Radstock,[33] although it is intended to provide a continuous cycle route to Southampton and Portsmouth.

Radstock had a second railway station on the Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway extension to Bath, which closed to passengers in 1966. The stations were adjacent to each other in the centre of the town, and each had level crossings across the busy A367 road, causing long tailbacks at busy periods. The S&D line also carried substantial coal traffic. A spur from the Great Western line on to the S&D and continuing to Writhlington Colliery remained open for a few years after the railway's closure to passenger traffic, until the colliery closed in 1973.

Radstock is situated on the A367 between Bath and Shepton Mallet, and on the A362 between Farrington Gurney and Frome, very close to the A37. Radstock is approximately 19 miles (30 km) south of junction 18 of the M4 motorway at Bath.

Memorial Gardens

Since the closure of the railways the railway land in the centre of the town stood empty for many years. Most prominent was a green space between the museum and brook which housed a dis-used pit wheel on a low steel frame, which many passers-by mistook for a spinning wheel. There had long been an aspiration to develop a memorial park or garden on the site to commemorate both the mining history of the town and to provide a new setting for the town's war memorial.

In 2001 a local practice of landscape architects, New Leaf Studio were commissioned by Bath & North East Somerset Council to develop proposals for the land.[34] The first phase of the park, the Memorial gardens were then built for the Norton Radstock Town Council in 2005 to New leaf Studio's designs incorporating a new sculptural base for the old mine wheel by artist Sebastien Boyesen.[35]

The new Memorial Gardens incorporate the war memorial which was moved from Victoria Square as part of the project. The planting employs a naturalistic style with broad drifts of herbaceous perennials and grasses providing colour through a long season, extending through the winter with dry stems and seed heads.

Museum

The Radstock Museum is housed in the town's former market hall. The museum has a range of exhibits which offer an insight into north-east Somerset life since the 19th century. The museum was originally opened in 1989 in barns in Haydon, and moved to its current site in the restored and converted Victorian Market Hall, a grade II listed building dating from 1897[36] which was opened on 10 July 1999 by Loyd Grossman. Many of the exhibits relate to the now disused local Somerset coalfield and geology. Other areas include aspects of local history including the school and shops, a forge, carpenter's shop and exhibits relating to agriculture. Artefacts and memorabilia of the Somerset Coal Canal, Somerset and Dorset and Great Western Railways are also on display.[37]

Education

First schools for children up to 11 include St Mary’s C of E Primary School, St Nicholas C of E Primary School and Trinity Primary School.[38] In the neighbouring parish of Westfield lie Westfield Primary School and, for pupils with complex learning difficulties, Fosseway School.

Writhlington School in Radstock is a secondary school for pupils aged 11–18. It has specialist status as a Business and Enterprise College. The school has 1,242[39] pupils in both compulsory and sixth-form education. The school is notable for its orchid project,[40] which includes the biggest collection of orchids outside Kew Gardens and has won numerous awards including a gold medal at the 2009 Chelsea Flower Show.[41] The school has also won awards in business with its enterprise companies and was named the most enterprising school in England in 2006.[42]

The town is served by the Somer Valley site of Bath College, a further education college in neighbouring Westfield.

Sport and leisure

Radstock has a Non-League football club Radstock Town F.C. who play at The Southfields Recreation Ground.

Media

The local free newspaper, the Midsomer Norton, Radstock & District Journal, has its offices in the town.[43] The other local weekly paper is the Somerset Guardian, which is part of the Daily Mail and General Trust.[44] The monthly magazine, the Mendip Times, also includes local features. Somer Valley FM (97.5FM and online) is the Community Radio for the district.[45]

Religious sites

Radstock contains four churches, united under the umbrella of "Churches together in Radstock". There are frequent interfaith unity services in the town.

The Anglican parish church of St Nicholas has a west tower dating from the 15th century. The rest of the church was rebuilt in 1879 in Geometric style, by William Willcox. It is Grade II listed.[46]

Radstock Methodist Church was formed in 1842 but the present building opened in 1902.[47] It was damaged by a fire in 2004, and reopened in 2005.[48] Radstock Baptist Church, situated on Wells Hill, was founded in 1844.

Radstock was one of the missions established in 1913 by the Downside community. A temporary building of thin wooden beams and asbestos blocks was erected in 1913,[49] and dedicated to St Hugh. Its altar rails and benches came from Prior Park. Dom Mackey was succeeded in 1918 by Dom Ambrose Agius, who acquired a disused printing works, formerly a barn and converted it into the present church in Westfield, which opened in 1929. It was rebuilt after a serious fire in 1991. It has a statue of the patron on its façade.[50]

Radstock is also home to a Jehovah's Witness Kingdom Hall.

Notable people

- William Blacker (1843–1913), Australian politician

- L. J. F. Brimble (1904–65), botanist and editor of Nature magazine.[51]

- Frank Coombs (1906-1941), English painter and architect [52]

- Alick Grant (1916–2008), footballer for Aldershot, Leicester City, Derby County, Newport County and York City.

- Bill Hyman (1875–1959), Somerset County cricketer.

- Ernest Hyman (1904–1927), Yeovil Town footballer.[53][54][55]

- Frank Pratten (1886-1941), founder of F. Pratten and Co Ltd, manufacturer of prefabricated classrooms and other buildings.

References

- "Radstock Parish". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2013.)

- "Welcome to Norton Radstock Town Council". Norton Radstock Town Council. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- Robinson, Stephen (1992). Somerset Place Names. Wimborne: Dovecote Press. p. 114. ISBN 1-874336-03-2.

- Johnston, James B (1915). The place-names of England and Wales. J. Murray. p. 410.

- "Somerset Hundreds". GENUKI. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- Priestley, Joseph (1831). Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and Railways, of Great Britain P580. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- "Development Sites - Radstock" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Background to the threat proposed to Radstock". Radstock Action Group. Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "The Radstock (Foxcote) accident of 1876". Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Radstock Regeneration Principles". Bath & North East Somerset Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Clew, Kenneth R (1970). The Somersetshire Coal Canal and Railways. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4792-6.

- "Peak District Mines Historical Society". Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Bonsall, Penny (July 1986). "The Writhlington Miners Strike 1899". Five Arches. Radstock, Midsomer Norton and district museum. 2: 3–5.

- "List of Mines in Great Britain and the Isle of Man, 1908". Coal Mining Resource Centre. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- "Writhlington SSSI, Somerset". UK: Natural England. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Pollitta, Jessica R; Braddya, Simon J.; Dunlop, Jason A. (2003). "The phylogenetic position of the extinct arachnid order Phalangiotarbida Haase, 1890, with reference to the fauna from the Writhlington Geological Nature Reserve (Somerset, UK)". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. SCO. 94 (3): 243–59. doi:10.1017/S0263593300000651.

- Dunlop, JA (1994). "An Upper Carboniferous amblypygid from the Writhlington Geological Nature Reserve". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 105 (4): 245–50. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(08)80177-0. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- Duncan, I. J.; Titchener, F.; Briggs, D. E.G. (June 2003), "Decay and Disarticulation of the Cockroach: Implications for Preservation of the Blattoids of Writhlington (Upper Carboniferous), UK", PALAIOS, 18 (3): 256–65, doi:10.1669/0883-1351(2003)018<0256:dadotc>2.0.co;2

- "Writhlington" (PDF). SSSI citation sheet. UK: English Nature. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 May 2011. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Down, Christopher Gordon; Warrington, AJ (2005). The history of the Somerset coalfield. Radstock: Radstock Museum. ISBN 0-9551684-0-6.

- "Radstock's coal mining history". This is Wiltshire. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Down, Christopher Gordon; Warrington, AG (1972), The History of the Somerset Coalfield, David and Charles, p. 222, ISBN 0-7153-5406-X

- "A Brief History of the Bristol and Somerset Coalfield". The Mines of the Bristol and Somerset Coalfield. Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "Relationships / unit history of NORTON RADSTOCK". Vision of Britain. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- "Somerset North East: New Boundaries Calculation". Electoral Calculus: General Election Prediction. Archived from the original on 14 February 2009. Retrieved 19 September 2007.

- "Rural Landscapes — Area 8 Farrington Gurney Farmlands". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 21 July 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- "UK Coal resource for new exploitation technologies" (PDF). DTI Cleaner Coal Technology Transfer Programme. Department for Business Innovation and Skills. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Collier, Peter (1986). Colliers Way: The Somerset Coalfield. Ex Libris Press. ISBN 978-0-948578-05-2.

- "Rural Areas — Area 15 Norton Radstock Southern Farmlands" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- "South West England: climate". Met Office. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- "The Colliers Way (NCN24)". BANES cycling. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2006.

- "OpenCcyleMap Cycle Map". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "Colliers Way". Sustrans. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Town centre memorial park, Radstock". New Leaf Studio. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- "Pit Head Wheel". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Radstock Market Hall". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- "Radstock Museum". Radstock Museum. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Education". Radstock Town Council. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- "Writhlington School". Ofsted. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2009.

- "WSBEorchids". WSBEorchids. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2008.

- "Chelsea Flower Show 2009: Continuous Learning Awards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 May 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- "WSBE Orchids". About. Archived from the original on 16 November 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Tindle Newspapers Ltd". The Newspaper Society. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- "Somerset Guardian". British Newspapers Online. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- "About Somer Valley FM". Somer Valley FM. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Church of St Nicholas". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- "The Baptist Church, Wells Hill". Radstock 4 u. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "Radstock Methodist Church". Churches together in Radstock. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- "St Hugh's RC". Churches together in Radstock. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Harding, John Anthony (1999). Diocese of Clifton, 1850–2000. Bristol: Clifton Catholic Diocesan Trustees. ISBN 978-0-9536689-0-8.

- "NLM", British Medical Journal, USA: NIH, 2 (5474): 1374, PMC 1846778

- "Frank Coombs (1906–1941)". Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- "RootsWeb's WorldConnect Project: Somerset Coalfield Connections". Wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "Yeovil Town Story Part 4". Ciderspace.co.uk. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- "The Graveyard Detective: Football Fatality". Graveyarddetective.blogspot.com. 9 May 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Radstock. |