Gastrodiscoides

Gastrodiscoides is genus of zoonotic trematode under the class Trematoda. It has only one species, Gastrodiscoides hominis. It is a parasite of a variety of vertebrates, including humans. The first definitive specimen was described from a human subject in 1876.[1] It is prevalent in Bangladesh, India, Burma, China, Kazakhstan, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Volga Delta of Russia,[2][3] with isolated cases from Africa, such as Nigeria.[4] It is especially notable in the Assam, Bengal, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and Uttar Pradesh regions of India.[5][2]

| Gastrodiscoides | |

|---|---|

| |

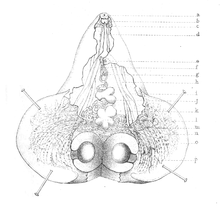

| Longitudinal section of an adult | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Gastrodiscoides Leiper, 1913 |

| Species: | G. hominis |

| Binomial name | |

| Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis and McConnell, 1876) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Gastrodiscus hominis Fischoeder | |

It is also known as the colonic fluke, particularly when infecting other animals. Its natural habitat is the colon of pigs, and has also been found in rhesus monkeys, orang-utans, fish, field rats and Napu mouse-deer. In humans the habitat is on the wall of the caecum.[6][7] Humans are considered an accidental host, as the parasite can survive without humans. It causes a helminthic disease called gastrodiscoidiasis.[6][7]

History of discovery

G. humanis is unique among helminths because it was first discovered and described from a human infection. The worm was discovered and described by two British medical doctors, Timothy Richard Lewis and James McConnell, in 1876, from the caecum of an Assamese man in India. Their description of the internal structure was inaccurate and incomplete. They claimed that the parasite had one testis and one ovary. They placed it in the genus Amphistomum, because of its obvious location of posterior sucker; the species was named Amphistomum hominis, as it was found in human.[8] In 1902, F. Fischoeder recognised the affinity with other species and tentatively placed it in the genus Gastrodiscus (Leuckart, 1877). However, the generic name was largely recognised as a synonym; it was then known as Amphistomum (Gastrodiscus) hominis. With a fresh look, J. W. W. Stephens re-described the parasite in 1906, and clearly noted the overlooked relatively small ovary and interpretation of the posterior testis as an ovary in the original description.[8]

A new helminthologist at the London School of Tropical Medicine, Robert T. Leiper, re-examined the parasite in 1913. He noted the distinctive characters such as a tuberculated genital cone, the position of the genital orifice, a smooth ventral disc, and the testes in tandem position. These outstanding features prompted him to create an entirely new genus, Gastrodiscoides, for the specimen.[9] This taxonomic revision had criticism, as some of the descriptions were later found to be flawed, such as the position of testes; these criticisms prevented it from coming into general acceptance. It was later observed that the parasite was much more common to pigs and other mammals than in humans. The first report of infection of pigs was in Cochinchina, Vietnam, in 1911. In 1913, it was further confirmed that the rate of porcine infection was as high as 5%. Then a large number of living flukes was recovered from dead Napu mouse-deer at the Zoological Gardens of the Zoological Society of London. The mouse-deer was Prince of Wales's collection from Malay. The shortcomings of Leiper's descriptions did not prevent the generic name Gastrodiscoides becoming more and more advocated in the early 1920s.[8] The currently accepted nomenclature was fortified by the British parasitologist J. J. C. Buckley, at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (where he was then a Milner Research Fellow), whose descriptions were based on high incidence of the parasitism among the Assamese in India. His first report in 1939,[1] followed by a body of evidences in support of Leiper's proposition, enabled him to vindicate the validity of a separate genus, Gastrodiscoides, hence the binomial name Gastrodiscoides hominis.[10] His report was the pioneer description of the life cycle of the fluke and the prevalence of gastrodiscoidiasis.[1] In his survey of three villages in Assam, there was found a surprisingly high incidence, with over 40% of the population was infected. J. J. C. Buckley's report is the most useful to the modern classification of G. hominis.[11]

Description

It is typically an amphistome with the ventral sucker close to the posterior end. The body is bilaterally symmetrical and is acoelomate. It is dorsoventrally flatted, with a unique pyramidal shape. The body is covered by a tegument bearing numerous tubercles.[12] The alimentary canal is incomplete, consisting of a pair of lateral pouches arising from the oral sucker and a pharyngeal tube, which bifurcates into two gut caeca. The bladder is in the middle behind the ventral sucker. The genus is hermaphrodite, as both male and female reproductive system are present.[6][8]

It is a large fluke, vase-shaped, and bright-pink in colour. In average it measures 5–8 mm long and 3–5 mm wide. The disc-shaped body is divisible into anterior conical and posterior discoidal regions. The anterior region is a conical projection bearing a prominent oral sucker. The posterior portion is relatively broad, up to 8 mm wide, discoidal, and ventrally excavated. It is an amphistome worm such that the ventral sucker is close to the posterior end.[13] The body covering, called a tegument, is smooth in appearance, but contains a fine structure in a series of concentric folds bearing numerous tightly packed tubercles. Ventral surface contains a specialised region of the tegument. Ciliated and non-ciliated papillae are arranged around the oral sucker.[14][15] The incomplete alimentary canal consists of a pair of lateral pouches arising from the oral sucker and a slightly tortuous pharyngeal tube, which bifurcates into two gut caeca. The large excretory bladder is in the middle, behind the ventral sucker. The species, being hermaphrodite, has both male and female reproductive systems, arranged in the posterior region. The testes lie in alongside the bifurcation of the caeca, and a common genital pore is on the cone just anterior to the bifurcation. The oval-shaped ovary lies just posterior to the testes in the middle, and the loosely coiled uterus opens to the genital pore. Vitelline glands are scattered around the caeca.[8]

Biology

Humans are now considered as the accidental host because humans are not the primary requirement for the life cycle; pigs are recognised as the principal definitive host. Infection causes a helminthic disease called gastrodiscoidiasis.[6] It is a digenetic trematode with a complex life cycle involving asexual reproduction in an intermediate host, presumably aquatic snails, and sexual reproduction in the vertebrate host. As a hermaphrodite, eggs are produced by self-fertilisation and are released along the faeces of the host. Eggs measure ~146 by 66 μm, are rhomboidal in shape, transparent, and green in colour. Each egg contains about 24 vitelline cells and a central unembryonated ovum. Eggs in a wet environment hatch into miracidia in 9–14 days.

In water, eggs hatch into miracidia, which then infect a mollusc, in which larval development and fission occurs. The miracidium grows into the sporocyst stage. It is generally conceived that the unfertilised eggs are ingested by the snail, but there has been no direct observation. In an experimental infection of the mollusc Helicorbis coenosus, miracidum develops into cercaria after 28–153 days of ingestion.[16] In the snail, mother and daughter rediae are found in the digestive gland, and are about 148–747/45–140 μm in size, sausage-shaped, and lack collar and locomotory organs.

Infective cercariae are produced and are released on water plants or directly infect other aquatic animals, such as fish.[17] The cercariae released from the snail form metacercarial cysts on water plants. The complete life cycle is not yet observed in nature,[18] and the tiny snail, H. coenosus, remains the most commonly accepted vector, as it is coincidentally found in abundance in the pigsties. In some circumstances, fishes and other aquatic animals are found to be infected. It is hypothesised that the free cercaria in water bodies accidentally find and penetrate these animals as second intermediate host, where they encsyt as metacercaria. These are directly infective to mammals upon consumption, while they get attached to vegetation, where night soil is used.

Humans ingest the metacercaria either by the infected fish or contaminated vegetable. The parasite travels through the digestive tract into the duodenum, then continues down to reach the caecum, where it self-fertilizes and lay eggs, continuing the cycle. Heavy infection in humans is suspected to cause diarrhoea, fever, abdominal pain, colic, malnutrition, anaemia, and even death.[2][4]

Pathogenicity and pathology

Gastrodiscoidiasis is an infection that is usually asymptomatic and affects the small intestine in animals, such as pigs, to a very mild symptom, but when it occurs in humans it can cause serious health problems and even death. It is suspected to cause diarrhoea, fever, abdominal pain, colic, and an increased mucous production. In severe cases, where there are large amounts of eggs present, tissue reactions can occur in the heart or mesenteric lymphatics, and even death may occur if left neglected. Indeed, a number of mortality among Assamese children is attributed to this infection.[2] In pigs, pathological symptoms include infiltration with eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. The submucosa can show oedema and thickening, resulting in a subacute inflammation of the caecum and mucoid diarrhoea.[6]

Epidemiology

Human gastrodiscoidiasis is endemic in Assam, and to a lesser extent in the Philippines. The highest incidence so far recorded is among children in Kamrup district of Assam, where the prevalence was as high as 41%.[1] First described from an Indian patient, it was initially believed to have a distribution restricted to India and the southeast Asia. Later investigations revealed that it is widespread, and is further spread by infected persons to other parts of the world, such as Guyana.[2] The level of infection in laboratory animals can be very high among Asian mammals.[13] Regions of high incidence can be attributed to low standard of sanitation, such as rural farms and villages where night soils are used. Infection in both humans and animals is most common through the ingestion of vegetation found in contaminated water. It is also assumed that transmission from infected fish that is under-cooked or eaten raw, as common among southeast Asian.[19] There is a unique case report of a seven-year-old Nigerian who showed symptoms of malnutrition and anaemia and was eventually diagnosed with infections of G. hominis and Ascaris lumbricoides. The child quickly recovered after proper medication.[4]

Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis is made by examination of the fæces and the detection of eggs. Adult worms are easily identified from other helminths by their distinctive appearance. The eggs are readily distinguished from those of other trematodes by their rhomboid shape and distinct green colour. Patients do not often directly show any symptoms, and if one appears, it indicates that the infection is already at a very high level. There is no prescribed treatment, but the traditional practice of soap enema has been very effective in removing the worms.[3] It works to flush the flukes from the colon which removes the parasite entirely, as it does not reproduce within the host. Some drugs that have been proven effective are tetrachloroethylene, at a dosage of 0.1 mg/kg on an empty stomach, and a more preferred drug, praziquantel, which eliminates the parasite with 3 doses at 25 mg/kg in one day.[6] Mebendazole was found to be efficient in deworming the parasite from a Nigerian girl who was shedding thousands of parasite eggs in stools even with a single dose of 500 mg.[4] Prevention of this disease is not difficult when simple sanitary measures are taken. Night soil should never be used as a fertilizer because it could contain any number of parasites. Vegetables should be washed thoroughly, and meat properly cooked.[7]

References

- Buckley JJC (1939). "Observations on Gastrodiscoides hominis and Fasciolopsis in Assam". Journal of Helminthology. 17 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00030972.

- Mas-Coma S, Bargues MD, Valero MA (2006). "Gastrodiscoidiasis, a plant-borne zoonotic disease caused by the intestinal amphistome fluke Gastrodiscoides hominis (Trematoda: Gastrodiscidae)". Revista Ibérica de Parasitología. 66 (1–4): 75–81. ISSN 0034-9623. Archived from the original on 2014-05-03.

- Kumar V (1980). "The digenetic trematodes, Fasciolopsis buski, Gastrodiscoides hominis and Artyfechinostomum malayanum, as zoonotic infections in South Asian countries". Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 60 (4): 331–339. PMID 7016049.

- Dada-Adegbola HO, Falade CO, Oluwatoba OA, Abiodun OO (2004). "Gastrodiscoides hominis infection in a Nigerian-case report". West African Journal of Medicine. 23 (2): 185–186. doi:10.4314/wajm.v23i2.28116. PMID 15287303.

- Murty CV, Reddy CR (1980). "A case report of Gastrodiscoides hominis infestation". Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 23 (4): 303–304. PMID 7228220.

- Liu D (2012). Molecular Detection of Human Parasitic Pathogens. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 365–368. ISBN 978-1-4398-1242-6.

- Müller R, Wakelin D (2001). Worms and Human Disease. CABI Publishing, Oxon, UK. pp. 55–56. ISBN 0851995160.

- Khalil M (1923). "A description of Gastrodiscoides hominis, from the Napu mouse deer". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 16 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1177/003591572301602102. PMC 2103306. PMID 19983413.

- Leiper RT (1913). "Observations on certain helminths of Man". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 6 (8): 265–297. doi:10.1016/S0035-9203(13)90201-7.

- Buckley JJC (1964). "The problem of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis and McConnell, 1876) Leiper, 1913". Journal of Helminthology. 38 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00033514. PMID 14125103.

- Buckley JJC (1964). "The problem of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis and McConnell, 1876) Leiper, 1913". Journal of Helminthology. 38 (1–2): 1–6. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00033514. PMID 14125103.

- Tandon V, Maitra SC (1983). "Surface morphology of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis & McConnell, 1876) Leiper, 1913 (Trematoda: Digenea) as revealed by scanning electron microscopy". Journal of Helminthology. 57 (4): 339–342. doi:10.1017/s0022149x00011056. PMID 6668422.

- Baker DG (2008). Flynn's Parasites of Laboratory Animals (2 ed.). Blackwell Publishers. p. 703. ISBN 978-0470344170.

- Brennan GP, Hanna RE, Nizami WA (1991). "Ultrastructural and histochemical observations on the tegument of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Paramphistoma: Digenea)". International Journal for Parasitology. 21 (8): 897–905. doi:10.1016/0020-7519(91)90164-3. PMID 1787030.

- Tandon V, Maitra SC (1983). "Surface morphology of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis & McConnell, 1876) Leiper, 1913 (Trematoda: Digenea) as revealed by scanning electron microscopy". Journal of Helminthology. 57 (4): 339–342. doi:10.1017/s0022149x00011056. PMID 6668422.

- Dutt SC, Srivastava HD (1966). "The intermediate host and the cercaria of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Trematoda: Gastrodiscidae). Preliminary report". Journal of Helminthology. 40 (1–2): 45–52. doi:10.1017/s0022149x00034076. PMID 5961529.

- Dutt SC, Srivastava HD (1972). "The life history of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis and McConnel, 1876) Leiper, 1913--the amphistome parasite of man and pig". Journal of Helminthology. 46 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00022100. PMID 5038423.

- Dutt SC, Srivastava HD (1972). "The life history of Gastrodiscoides hominis (Lewis and McConnel, 1876) Leiper, 1913--the amphistome parasite of man and pig". Journal of Helminthology. 46 (1): 35–46. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00022100. PMID 5038423.

- Chai JY, Shin EH, Lee SH, Rim HJ (2009). "Foodborne intestinal flukes in Southeast Asia". The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 47 (Suppl): 69–102. doi:10.3347/kjp.2009.47.S.S69. PMC 2769220. PMID 19885337.

External links

- Gastrodiscoides taxonomy at UniProt

- Gastrodiscoides hominis taxonomy at UniProt

- Taxonomy and nomenclature in ITIS Report

- NCBI Taxonomic Browser

- Classification at Encyclopedia of Life

- Taxonomy at ZipcodeZoo

- Taxonomy at Taxonomicon

- Molecular data at NEHU NEPID

- Information at Comparative Toxicogenomics Database

- Taxonomy at Fauna Europaea

- Molecular database at BOLDSYSTEMS

- Morphological description at Stanford

- Gastrodiscoidisis at Stanford site

- The Merck Veterinary Manual: Zoonotic Diseases

- NCBI Taxonomy Browser

- Universal Biological Indexer and Organizer

- Description at North Eastern Hill University

- Clinical Description at BioPortal

- Description at Expert Consult

- Diagnosis at Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

- Classification at Schistosomiasis Research Group