Gallo-Romance languages

The Gallo-Romance branch of the Romance languages includes in the narrowest sense French, Occitan, and Franco-Provençal (Arpitan).[2][3][4] However, other definitions are far broader, variously encompassing Catalan, the Gallo-Italic languages,[5] and the Rhaeto-Romance languages.[6]

| Gallo-Romance | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution |

|

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

Early form | Old Gallo-Romance

|

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | nort3208[1] |

Old Gallo-Romance was one of the three languages in which the Oaths of Strasbourg were written in 842 AD.

Classification

The Gallo-Romance group includes:

- The Oïl languages. These include French, Orleanais, Gallo, Angevin, Tourangeau, Saintongeais, Poitevin, Bourgignon, Picard, Walloon, Lorrain and Norman.[7]

- Arpitan, also known as Franco-Provençal, of southeastern France, western Switzerland, and Aosta Valley region of northwestern Italy. Formerly thought of as a dialect of either Oïl or Occitan, it is linguistically a language on its own, or rather a separate group of languages, as many of its dialects have little mutual comprehensibility. It shares features of both French and the Provençal dialect of Occitan.

- Occitan, or the langue d'oc, has dialects such as Provençal, and Gascon-Aranese.[8]

Other language families which are sometimes included in Gallo-Romance:

- Catalan, with standard forms of Catalan and Valencian. The inclusion of Catalan in Gallo-Romance is disputed by some linguists who prefer to group it with Iberian Romance.[9] In general, however, modern Catalan, especially grammatically, remains closer to modern Occitan than to either Spanish or Portuguese.

- The Rhaeto-Romance languages, including Romansh of Switzerland, Ladin of the Dolomites area, and Friulian of Friuli. Rhaeto-Romance can be classified as Gallo-Romance, or as a separate branch within the Western Romance languages. Rhaeto-Romance is a diverse group, with the Italian varieties influenced by Venetian and Italian and Romansh by Franco-Provençal.

- The Gallo-Italic languages. They include Piedmontese, Ligurian, Western and Eastern Lombard, Emilian, Romagnol, Gallo-Italic of Sicily and Gallo-Italic of Basilicata. Venetian is also part of the Gallo-Italic branch according both to Ethnologue[10] and Glottolog.[11] Gallo-Italic can be classified as Gallo-Romance or as a branch of the Western Romance languages. Ligurian (and Venetian if considered) retain the final -o, being the exceptions in Gallo-Romance.

In the view of some linguists (Pierre Bec, Andreas Schorta, Heinrich Schmid, Geoffrey Hull) Rhaeto-Romance and Gallo-Italic form a single linguistic unity named "Rhaeto-Cisalpine" or "Padanian", which includes also the Venetian and Istriot dialects, whose Italianate features are deemed to be superficial and secondary in nature.[12]

Traditional geographical extension

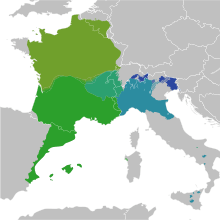

How far the Gallo-Romance languages spread varies a great deal depending on which languages are included in the group. Those included in its narrowest definition (i.e. the Langues d'oïl and Arpitan) were historically spoken in the north of France, parts of Flanders, Alsace, part of Lorraine, the Wallonia region of Belgium, the Channel Islands, parts of Switzerland, and northern Italy.

Today, a single Gallo-Romance language (French) dominates much of this geographic region (including the formerly non-Romance areas of France) and has also spread overseas.

At its broadest, the area also encompasses southern France, Catalonia, the Valencian Country and the Balearic islands in eastern Spain, and much of northern Italy.

General characteristics

The Gallo-Romance languages are generally considered the most innovative (least conservative) among the Romance languages. Northern France (the medieval area of the langue d'oïl, from which modern French developed) was the epicentre. Characteristic Gallo-Romance features generally developed earliest and appear in their most extreme manifestation in the langue d'oïl, gradually spreading out from there along riverways and roads. The earliest vernacular Romance writing occurred in Northern France, as the development of vernacular writing in a given area was forced by the almost total inability of Romance speakers to understand Classical Latin, still the vehicle of writing and culture.

Gallo-Romance languages are usually characterised by the loss of all unstressed final vowels other than /-a/ (most significantly, final /-o/ and /-e/ were lost). However, when the loss of a final vowel would result in an impossible final cluster (e.g. /tr/), a prop vowel appears in place of the lost vowel, usually /e/. Generally, the same changes also occurred in final syllables closed by a consonant.

Furthermore, loss of /e/ in a final syllable was early enough in Primitive Old French that the Classical Latin third singular /t/ was often preserved: venit "he comes" > /ˈvɛːnet/ (Romance vowel changes) > /ˈvjɛnet/ (diphthongization) > /ˈvjɛned/ (lenition) > /ˈvjɛnd/ (Gallo-Romance final vowel loss) > /ˈvjɛnt/ (final devoicing). Elsewhere, final vowel loss occurred later or unprotected /t/ was lost earlier (perhaps under Italian influence).

Other than southern Occitano-Romance, the Gallo-Romance languages are quite innovative, with French and some of the Gallo-Italian languages rivaling each other for the most extreme phonological changes compared with more conservative languages. For example, French sain, saint, sein, ceint, seing meaning "healthy, holy, breast, (he) girds, signature" (Latin sānum, sanctum, sinum, cinget, signum) are all pronounced /sɛ̃/.

In other ways, however, the Gallo-Romance languages are conservative. The older stages of many of the languages are famous for preserving a two-case system consisting of nominative and oblique, fully marked on nouns, adjectives and determiners, inherited almost directly from the Latin nominative and accusative cases and preserving a number of different declensional classes and irregular forms.

In the opposite of the normal pattern, the languages closest to the oïl epicentre preserve the case system the best, and languages at the periphery (near languages that had long before lost the case system except on pronouns) lost it early. For example, the case system was preserved in Old Occitan until around the 13th century but had already been lost in Old Catalan, despite the fact that there were very few other differences between the two.

The Occitan group is known for an innovatory /ɡ/ ending on many subjunctive and preterite verbs and an unusual development of [ð] (Latin intervocalic -d-), which, in many varieties, merges with [dz] (from intervocalic palatalised -c- and -ty-).

The following tables show two examples of the extensive phonological changes that French has undergone. (Compare modern Italian saputo, vita even more conservative than the reconstructed Western Romance forms.)

| Language | Change | Form | Pronun. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulgar Latin | – | saˈpūtum | /saˈpuːtũː/ |

| Western Romance | vowel changes, first lenition | /saˈbuːdo/ | |

| Gallo-Romance | loss of final vowels | /saˈbuːd/ | |

| second lenition | /saˈvuːð/ | ||

| pre-French | final devoicing, loss of length | /saˈvuθ/ | |

| loss of /v/ near rounded vowel | /səˈuθ/ | ||

| early Old French | fronting of /u/ | seüṭ | /səˈyθ/ |

| Old French | loss of dental fricatives | seü | /səˈy/ |

| French | collapse of hiatus | su | /sy/ |

| Language | Change | Form | Pronun. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vulgar Latin | – | vītam | /ˈviːtãː/ |

| Western Romance | vowel changes, first lenition | /ˈviːda/ | |

| early Old French | second lenition, loss of length, final /a/ to /ə/ | viḍe | /ˈviðə/ |

| Old French | loss of dental fricatives | vie | /ˈviə/ |

| French | loss of final schwa | vie | /vi/ |

These are the notable characteristics of the Gallo-Romance languages:

- Early loss of all final vowels other than /a/ is the defining characteristic, as noted above.

- Further reductions of final vowels in langue d'oïl and many Gallo-Italic languages, with the feminine /a/ and prop vowel /e/ merging into /ə/, which is often subsequently dropped.

- Early, heavy reduction of unstressed vowels in the interior of a word (another defining characteristic). That and final vowel reduction are most of the extreme phonemic differences between the Northern and the Central Italian dialects, which otherwise share a great deal of vocabulary and syntax.

- Loss of final vowels phonemicised the long vowels that had been automatic concomitants of stressed open syllables. The phonemic long vowels are maintained directly in many Northern Italian dialects. Elsewhere, phonemic length was lost, but many of the long vowels had been diphthongised, resulting in a maintenance of the original distinction. The langue d'oïl branch was again at the forefront of innovation, with no less than five of the seven long vowels diphthongising (only high vowels were spared).

- Front rounded vowels are present in all branches except Catalan. /u/ usually fronts to /y/ (typically along with a shift of /o/ to /u/), and mid-front rounded vowels /ø ~ œ/ often develop from long /oː/ or /ɔː/.

- Extreme lenition (repeated lenition) occurs in many languages, especially in langue d'oïl and many Gallo-Italian languages. Examples from French: ˈvītam > vie /vi/ "life"; *saˈpūtum > su /sy/ "known"; similarly vu /vy/ "seen" < *vidūtum, pu /py/ "been able" < *potūtum, eu /y/ "had" < *habūtum. Examples from Lombard: *"căsa" > "cà" /ka/ "home, house"

- Most of langue d'oïl (except Norman and Picard dialects), Swiss Rhaeto-Romance languages and many northern dialects of Occitan have a secondary palatalization of /k/ and /ɡ/ before /a/, producing different results from the primary Romance palatalisation: centum "hundred" > cent /sɑ̃/, cantum "song" > chant /ʃɑ̃/.

- Other than Occitano-Romance languages, most Gallo-Romance languages are subject-obligatory (whereas all the rest of the Romance languages are pro-drop languages). This is a late development triggered by progressive phonetic erosion: Old French was still a null-subject language until the loss of secondary final consonants in Middle French caused spoken verb forms (e.g. aime/aimes/aiment; viens/vient) to coincide.

Gallo-Italian languages have a number of features in common with the other Italian languages:

- Loss of final /s/, which triggers raising of the preceding vowel (more properly, the /s/ "debuccalises" to /j/, which is monophthongised into a higher vowel): /-as/ > /-e/, /-es/ > /-i/, hence Standard Italian plural cani < canes, subjunctive tu canti < tū cantēs, indicative tu cante < tū cantās (now tu canti in Standard Italian, borrowed from the subjunctive); amiche "female friends" < amīcās. The palatalisation in the masculine amici /aˈmitʃi/, compared with the lack of palatalisation in amiche /aˈmike/, shows that feminine -e cannot come from Latin -ae, which became /ɛː/ by the first century AD, and would certainly have triggered palatalisation.

- Use of nominative -i for masculine plurals instead of accusative -os.

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Northwestern Shifted Romance". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Charles Camproux, Les langues romanes, PUF 1974. p. 77–78.

- Pierre Bec, La langue occitane, éditions PUF, Paris, 1963. p. 49–50.

- Ledgeway, Adam; Maiden, Martin (2016-09-05). The Oxford Guide to the Romance Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 292 & 319. ISBN 9780191063251.

- Tamburelli, M., & Brasca, L. (2018). Revisiting the classification of Gallo-Italic: a dialectometric approach. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 33, 442-455. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqx041

- G.B. Pellegrini, "Il cisalpino ed il retoromanzo, 1993". See also "The Dialects of Italy", edited by Maiden & Parry, 1997

- Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (2011). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780521800723.

- Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (2013-10-24). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages: Volume 2, Contexts. Cambridge University Press. p. 173. ISBN 9781316025550.

- Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (2013-10-24). The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages: Volume 2, Contexts. Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9781316025550.

- https://www.ethnologue.com/language/vec

- https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/istr1244

- The most developed formulation of this theory is to be found in the research of Geoffrey Hull, "La lingua padanese: Corollario dell’unità dei dialetti reto-cisalpini". Etnie: Scienze politica e cultura dei popoli minoritari, 13 (1987), pp. 50-53; 14 (1988), pp. 66-70, and The Linguistic Unity of Northern Italy and Rhaetia: Historical Grammar of the Padanian Language, 2 vols. Sydney: Beta Crucis, 2017..