Foreign policy of Vladimir Putin

The foreign policy of Vladimir Putin concerns the policies of Russia's president Vladimir Putin with respect to other nations. He held office from 2000 to 2008, and assumed power again in 2012.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Incumbent Policies Elections Premiership

Media gallery |

||

As of late 2013, Russia–United States relations were at a low point.[1] The United States canceled a summit (for the first time since 1960), after Putin gave asylum to Edward Snowden. Washington regarded Russia as obstructionist and a spoiler regarding Syria, Iran, Cuba and Venezuela. In turn, those nations look to Russia for protection against the United States.[1] Europe needs Russian gas, but worries about interference in the affairs of Eastern Europe. Expansion of NATO into Eastern Europe conflicts with Russian interests. In Asia, India has moved from a close ally of the Soviet Union to a partner of the United States with strong nuclear and commercial ties. Japan and Russia remain at odds over the ownership of the Kurile islands; this dispute has hindered cooperation for decades.[1] China has moved to become a close ally of Russia.[1]

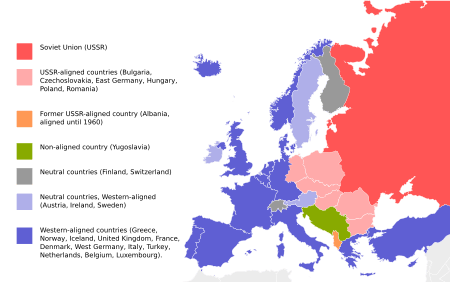

In 2014, with NATO's decision to suspend practical co-operation with Russia and all major Western countries' decision to impose a host of sanctions against Russia, in response to the Russian military intervention in Ukraine, Russia's relationship with the West came to be characterized as assuming an adversarial nature, or the advent of Cold War II.[2][3][4]

Relations with NATO and its member nations

After the 9/11 attacks, Putin supported the U.S. in the War on Terror, thus creating an opportunity for deepening the relationship with the leading Western and NATO power.[5]. On 13 December 2001, Bush gave Russia notice of the United States' unilateral withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.[6]. From Russia's point of view, the US withdrawal from the agreement, which ensured strategic parity between the parties, destroyed hopes for a new partnership.[7]. Russia opposed the expansion of NATO which happened at the 2002 Prague summit.[5] Since 2003, when Russia did not support the Iraq War and when Putin became ever more distant from the West in his internal and external policies, the relations remained strained. In an interview with Michael Stürmer, Putin was quoted saying that there were three questions which most concerned Russia and Eastern Europe; namely the status of Kosovo, the Conventional Forces in Europe treaty and American plans to build missile defence sites in Poland and the Czech Republic, and suggested that all three were some way linked.[8] In Putin's view, concessions on one of these questions on the Western side might be met with concessions from Russia on another.[8]

In February 2007, at the annual Munich Conference on Security Policy, Putin openly criticized what he called the United States' monopolistic dominance in global relations, and "almost uncontained hyper use of force in international relations".[9] In this speech, which became known as Munich Speech, Putin called for a "fair and democratic world order that would ensure security and prosperity not only for a select few, but for all".[9] His remarks however were met with criticism by some delegates[10] such as former NATO secretary Jaap de Hoop Scheffer who called his speech, "disappointing and not helpful."[11] The months following Putin's Munich speech[9] were marked by tension and a surge in rhetoric on both sides of the Atlantic. Both Russian and American officials, however, denied the idea of a new Cold War.[12] Then US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said on the Munich Conference: "We all face many common problems and challenges that must be addressed in partnership with other countries, including Russia. ... One Cold War was quite enough."[13] Vladimir Putin said prior to 33rd G8 Summit, on June 4: "we do not want confrontation; we want to engage in dialogue. However, we want a dialogue that acknowledges the equality of both parties’ interests."[14]

In June 2007, when answering a question about whether Russian nuclear forces might be focused on European targets in case "the United States continued building a strategic shield in Poland and the Czech Republic", Putin admitted: "if part of the United States’ nuclear capability is situated in Europe and that our military experts consider that they represent a potential threat, then we will have to take appropriate retaliatory steps. What steps? Of course we must have new targets in Europe."[14][15][16]

Putin continued his public opposition of a U.S. missile shield in Europe, and presented President George W. Bush with a counterproposal on June 7, 2007 of sharing the use of the Soviet-era radar system in Azerbaijan rather than building a new system in the Czech Republic. Putin expressed readiness to modernize the Gabala radar station, which has been in operation since 1986. Putin proposed it would not be necessary to place interceptor missiles in Poland then, but interceptors could be placed in NATO member Turkey or Iraq. Putin suggested also equal involvement of interested European countries in the project.[17]

In his annual address to the Federal Assembly on 26 April 2007, Putin announced plans to declare a moratorium on the observance of the CFE Treaty by Russia until all NATO members ratified it and started observing its provisions, as Russia had been doing on a unilateral basis. Putin argues that as new NATO members have not even signed the treaty so far, an imbalance in the presence of NATO and Russian armed forces in Europe creates a real threat and an unpredictable situation for Russia.[18] NATO members said they would refuse to ratify the treaty until Russia complied with its 1999 commitments made in Istanbul whereby Russia should remove troops and military equipment from Moldova and Georgia. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov was quoted as saying in response that "Russia has long since fulfilled all its Istanbul obligations relevant to CFE".[19] Russia suspended its participation in the CFE as of midnight Moscow time on December 11, 2007.[20][21] On December 12, 2007, the United States officially said it "deeply regretted the Russian Federation's decision to 'suspend' implementation of its obligations under the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE)." State Department spokesman Sean McCormack, in a written statement, added that "Russia's conventional forces are the largest on the European continent, and its unilateral action damages this successful arms control regime."[22] NATO's primary concern arising from Russia's suspension is that Moscow could now accelerate its military presence in the Northern Caucasus.[23]

Putin strongly opposed the secession of Kosovo from Serbia. He called any support for this act "immoral" and "illegal".[24] He described Kosovo's declaration of independence a "terrible precedent" that will come back to hit the West "in the face".[25] He stated that the Kosovo precedent will de facto destroy the whole system of international relations, developed over centuries.[26]

Putin's relations with former British Prime Minister Tony Blair, former German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, former French Presidents Jacques Chirac, and Nicolas Sarkozy and Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi were reported to be personally friendly. Putin's "cooler" and "more business-like" relationship with Germany's subsequent Chancellor, Angela Merkel is often attributed to Merkel's upbringing in the former DDR, where Putin was stationed when he was a KGB agent.[27]

By mid-2000s (decade), the relations between Russia and the United Kingdom deteriorated when the United Kingdom granted political asylum to Putin's former patron, oligarch Boris Berezovsky, in 2003.[28] Berezovsky, located in London, often criticized Putin.[28] The United Kingdom also granted asylum to the Chechen rebel leader Akhmed Zakayev and other notable persons who had fled Russia.

In 2006 President Putin introduced a law which restricted non-governmental organisations (NGOs) from getting funding from foreign governments. This resulted in many NGOs closing.[29]

The end of 2006 brought strained relations between Russia and Britain in the wake of the death of Alexander Litvinenko in London by poisoning. On 20 July 2007, the Gordon Brown government expelled "four Russian envoys over Putin's refusal to extradite ex-KGB agent Andrei Lugovoi, wanted in the UK for the murder of fellow former spy Alexander Litvinenko in London."[28] The Russian government, among other things, said it would suspend issuing visas to UK officials and froze cooperation on counterterrorism in response to Britain suspending contacts with their Federal Security Service.[28] Alexander Shokhin, president of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs warned that British investors in Russia will "face greater scrutiny from tax and regulatory authorities. [And] They could also lose out in government tenders". On December 10, 2007, Russia ordered the British Council to halt work at its regional offices in what was seen as the latest round of a dispute over the murder of Alexander Litvinenko; Britain said Russia's move was illegal.[30]

On 1 April 2014, NATO decided to suspend practical co-operation with Russia, in response to the Ukraine crisis.[31]

Putin has denounced the idea of "American exceptionalism".[32] Putin has brought up police behavior in Ferguson in response to criticisms of democracy in Russia.[33]

A report released in November 2014 highlighted the fact that close military encounters between Russia and the West (mainly NATO countries) had jumped to Cold War levels, with 40 dangerous or sensitive incidents recorded in the eight months alone, including a near-collision between a Russian reconnaissance plane and a passenger plane taking off from Denmark in March 2014 with 132 passengers on board.[34] The 2014 unprecedented increase[35] in Russian air force and naval activity in the Baltic region prompted NATO to step up its longstanding rotation of military jets in Lithuania.[36] Similar Russian air force activity in the Asia-Pacific region, relying on the resumed use of the previously abandoned Soviet military base at Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, in 2014, was officially acknowledged by Russia in January 2015.[37] In March 2015, Russia's defense minister Sergey Shoygu said that Russia's long-range bombers would continue patrolling various parts of the world and expand into other regions.[38]

In July 2014, the U.S. formally accused Russia of having violated the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty by testing a prohibited medium-range ground-launched cruise missile (presumably R-500,[39] a modification of Iskander)[40] and threatened to retaliate accordingly.[40][41] In early June 2015, the U.S. State Department reported that Russia had failed to correct the violation of the I.N.F. Treaty; the U.S. government was said to have made no discernible headway in making Russia so much as acknowledge the compliance problem.[42] The US government's October 2014 report claimed that Russia had 1,643 nuclear warheads ready to launch (an increase from 1,537 in 2011) – one more than the US, thus overtaking the US for the first time since 2000; both countries' deployed capacity being in violation of the 2010 New START treaty that sets a cap of 1,550 nuclear warheads.[43][44] Likewise, even before 2014, the US had set about implementing a large-scale program, worth up to a trillion dollars, aimed at overall revitalization of its atomic energy industry, which includes plans for a new generation of weapon carriers and construction of such sites as the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico and the National Security Campus in south Kansas City.[45][46]

At the end of 2014, Putin approved a revised national military doctrine, which listed NATO’s military buildup near the Russian borders as the top military threat.[47][48]

In late June 2015, while on a trip to Estonia, US Defence Secretary Ashton Carter said the U.S. would deploy heavy weapons, including tanks, armoured vehicles and artillery, in Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania.[49] The move was interpreted by Western commentators as marking the beginning of a reorientation of NATO′s strategy.[50] It was called by a senior Russian Defence Ministry official ″the most aggressive act by Washington since the Cold War″[51] and criticised by the Russian Foreign Ministry as "inadequate in military terms" and "an obvious return by the United States and its allies to the schemes of ‘the Cold War’".[52][53] On its part, the U.S. expressed concern over Putin's announcement of plans to add over 40 new ballistic missiles to Russia′s nuclear weapons arsenal in 2015.[51] American observers and analysts, such as Steven Pifer, noting that the U.S. had no reason for alarm about the new missiles, provided that Russia remained within the limits of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), viewed the ratcheting-up of nuclear saber-rattling by Russia′s leadership as mainly bluff and bluster designed to conceal Russia′s weaknesses;[54] however, Pifer suggested that the most alarming motivation behind this rhetoric could be Putin seeing nuclear weapons not merely as tools of deterrence, but as tools of coercion.[55] Meanwhile, at the end of June 2015, it was reported that the production schedule for a new Russian MIRV-equipped, super-heavy thermonuclear intercontinental ballistic missile Sarmat, intended to replace the obsolete Soviet-era SS-18 Satan missiles, was slipping.[56] Also noted by commentators were the inevitable financial and technological constraints that would hamper any real arms race with the West, if such course were to be embarked on by Russia.[57]

Tensions in other European countries and relations with the former Soviet bloc

The Russian leadership under Putin sees the fracturing of the political unity within the EU and especially the political unity between the EU and the US as among its main strategic goals.[58] Russia seeks to gain dominant influence in former Eastern Bloc states that are culturally and historically close to it, corrode and undermine Western institutions and values, manipulate public opinion and policy-making throughout Europe.[58]

As the West supported Kosovo's independence, Russia later used the "Kosovo precedent" as justification for its annexation of Crimea and its support of breakaway states in Georgia and Moldova.[59][60]

In November 2014, the German government publicly voiced its concern about what it saw as efforts by Putin to spread Russia's ‘sphere of influence’ beyond former Soviet states in the Balkans in countries such as Serbia, Macedonia, Albania and Bosnia, which could impede those countries' progress towards membership in the European Union.[59][61]

A series of Europe's far-right and hard Eurosceptic political parties such as Bulgaria's Ataka, the Alternative for Germany, France's National Front, the Freedom Party of Austria, Italy's Northern League, the Independent Greeks and Hungary's Jobbik, have been reported to be courted or even funded by Russia.[62][63] Russia’s ideological approach to this type of activity is opportunistic: it supports both far-left and far-right groups, the aim being to exacerbate divides in Western states and destabilise the EU through fringe political parties gaining more clout.[64] The success of these parties in the May 2014 European elections caused concern that a coherent pro-Russian block was forming in the EU parliament.[65]

In early January 2015, public protests in Hungary broke out against Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán's perceived move towards Russia.[66] Previously, his government had negotiated secret loans from the Russians, awarded a major nuclear power contract to Rosatom, and made parliament give a green light to Russia’s gas pipeline project in contravention to blocking orders from Brussels.[67]

In early April 2015, the Polish border guard sources were cited as saying that Poland was preparing to build observation towers along its border with the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad;[68][69] the move was linked by the mass media to prior official vaguely-worded confirmation,[70] in December 2013, of Russia′s putative deployment of its advanced modification of nuclear-capable Iskander theatre ballistic missiles in the exclave′s territory,[71] as well as more recent, March 2015, unofficial reports of the same nature.[72]

The prime minister of Montenegro Milo Đukanović went on record in October 2015 to claim that Russia was sponsoring the anti-government and anti-NATO protests in Podgorica.[73][74]

Relations with South and East Asia

During his first and second term in office, bilateral trade turnover between India and Russia was modest and stood at US$3 billion, of which Indian exports to Russia were valued at US$908 million. The major Indian exports to Russia are pharmaceuticals; tea, coffee and spices; apparel and clothing; edible preparations; and engineering goods. Main Indian imports from Russia are iron and steel; fertilisers; non-ferrous metals; paper products; coal, coke & briquettes; cereals; and rubber. Indo-Russian trade is expected to reach US$10 billion by 2010. Putin wrote in an article in the Hindu, "The Declaration on Strategic Partnership between India and Russia signed in October 2000 became a truly historic step".[75][76] Prime Minister Manmohan Singh also agreed with his counterpart by stated in speech given during President Putin's 2012 visit to India, "President Putin is a valued friend of India and the original architect of the India-Russia strategic partnership".[77] Both countries closely collaborate on matters of shared national interest these include at the UN, BRICS, G20 and where India has observer status and has been asked by Russia to become a full member.[78] Russia also strongly supports India receiving a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. In addition, Russia has vocally backed India joining the NSG[79] and APEC.[80] Moreover, it has also expressed interest in joining SAARC with observer status in which India is a founding member.[81][82]

Russia currently is one of only two countries in the world (the other being Japan) that has a mechanism for annual ministerial-level defence reviews with India.[83] The Indo-Russian Inter-Governmental Commission (IRIGC), which is one of the largest and comprehensive governmental mechanisms that India has had with any country internationally. Almost every department from the Government of India attends it.[83]

Putin's Russia maintains strong and positive relations with other BRIC countries. The country has sought to strengthen ties especially with the People's Republic of China by signing the Treaty of Friendship as well as building the Trans-Siberian oil pipeline geared toward growing Chinese energy needs.[84] The mutual-security cooperation of the two countries and their central Asian neighbours is facilitated by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation which was founded in 2001 in Shanghai by the leaders of China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

_01.jpg)

Following the Peace Mission 2007 military exercises jointly conducted by the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) member states, Putin announced on 17 August 2007 the resumption on a permanent basis of long-distance patrol flights of The Russian Air Force Tu-95 and Tu-160 strategic bombers that had been suspended since 1992.[85][86] US State Department spokesman Sean McCormack was quoted as saying in response that "if Russia feels as though they want to take some of these old aircraft out of mothballs and get them flying again, that's their decision."[86] The announcement made during the SCO summit in the light of joint Russian-Chinese military exercises, first-ever in history to be held on Russian territory,[87] made some believe that Putin is inclined to set up an anti-NATO bloc or the Asian version of OPEC.[88] When presented with the suggestion that "Western observers are already likening the SCO to a military organisation that would stand in opposition to NATO", Putin answered that "this kind of comparison is inappropriate in both form and substance".[85] Russian Chief of the General Staff Yury Baluyevsky was quoted as saying that "there should be no talk of creating a military or political alliance or union of any kind, because this would contradict the founding principles of SCO".[87]

The resumption of long-distance flights of Russia's strategic bombers was followed by the announcement by Russian Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov during his meeting with Putin on December 5, 2007, that 11 ships, including the aircraft carrier Kuznetsov, would take part in the first major navy sortie into the Mediterranean since Soviet times.[89] The sortie was to be backed up by 47 aircraft, including strategic bombers.[90] According to Serdyukov, this was an effort to resume regular Russian naval patrols on the world's oceans, the view that was also supported by Russian media.[91] The military analyst from Novaya Gazeta Pavel Felgenhauer said that the accident-prone Kuznetsov was scarcely seaworthy and was more of a menace to her crew than any putative enemy.[92]

According to the Japan Times, Russia increased its economic support for North Korea in an attempt to balance against a potential US-led push to topple the Kim Jong-un regime.[93] In the event of regime collapse, Russia is worried about losing regional influence as well as the possibility of American troops being deployed to Russia's Eastern border.[93] TransTeleCom (TTK), one of Russia’s largest telecommunications companies, is also thought to provide a new internet connection to the country at a time when the US has engaged in denial of service attacks against North Korean hackers thought to be affiliated with the Reconnaissance General Bureau.[94][95]

Relations with Middle Eastern and North African countries

On 16 October 2007 Putin visited Iran to participate in the Second Caspian Summit in Tehran,[96][97] where he met with Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.[98] Other participants were leaders of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan.[99] This was the first visit of a Soviet or Russian leader to Iran since Joseph Stalin's participation in the Tehran Conference in 1943, and thus marked a significant event in Iran–Russia relations.[100] At a press conference after the summit Putin said that "all our (Caspian) states have the right to develop their peaceful nuclear programmes without any restrictions".[101] During the summit it was also agreed that its participants, under no circumstances, would let any third-party state use their territory as a base for aggression or military action against any other participant.[96]

Subsequently, under Medvedev's presidency, Iran–Russia relations were uneven: Russia did not fulfill the contract of selling to Iran the S-300, one of the most potent anti-aircraft missile systems currently existing. However, Russian specialists completed the construction of Iran and the Middle East's first civilian nuclear power facility, the Bushehr Nuclear Power Plant, and Russia has continuously opposed the imposition of economic sanctions on Iran by the U.S. and the EU, as well as warning against a military attack on Iran. Putin was quoted as describing Iran as a "partner",[8] though he expressed concerns over the Iranian nuclear programme.[8]

In April 2008, Putin visited Libya where he met the leader Muammar Gaddafi, the country welcomed the idea of creating an OPEC-like group of gas-exporting countries, Putin became first Russian President who visited Libya, he remarked the visit as "We are satisfied about the way in which we resolved this problem. I am absolutely convinced that the solution we have found will help the Russian and Libyan economies."[102] Putin condemned the foreign military intervention of Libya, he called UN resolution as "defective and flawed," and added "It allows everything. It resembles medieval calls for crusades.",[103] During the whole event, Putin condemned other steps taken by NATO.[104] Upon the death of Muammar Gaddafi, Putin called it as "planned murder" by US, he asked "They showed to the whole world how he (Gaddafi) was killed," and "There was blood all over. Is that what they call a democracy?"[105][106]

Dmitri Trenin reports in The New York Times that from 2000 to 2010 Russia sold around $1.5 billion worth of arms to Syria, making Damascus Moscow’s seventh-largest client.[107] During the Syrian civil war, Russia threatened to veto any sanctions against the Syrian government,[108] and continued to supply arms to the regime.

Putin opposed any foreign intervention. On 1 June 2012, in Paris, he rejected the statement of French President Francois Hollande who called on Bashar Al-Assad to step down. Putin echoed the argument of the Assad regime that anti-regime ’’militants’’ were responsible for much of the bloodshed, rather than the shelling by Syrian forces and the civilian killings attributed by survivors and Western governments toregime supporters. He asked "But how many of peaceful people (sic) were killed by so-called militants? Did you count? There are also hundreds of victims." He also talked about previous NATO interventions and their results, and asked "What is happening in Libya, in Iraq? Did they become safer? Where are they heading? Nobody has an answer."[109]

On 11 September 2013, an opinion, written by Putin, was published in The New York Times regarding international events related to the United States, Russia and Syria.[110]

Relations with post-Soviet states

A series of so-called color revolutions in the post-Soviet states, namely the Rose Revolution in Georgia in 2003, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004 and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan in 2005, led to frictions in the relations of those countries with Russia. In December 2004, Putin criticised the Rose and Orange Revolution, according to him: "If you have permanent revolutions you risk plunging the post-Soviet space into endless conflict".[111] During the protests following the 2011 Russian elections (in December 2011) Putin named the Orange Revolution as a potential precedent of what was going to happen in Russia.[112]

Apart from a clash of nationalist rhetorics with the common historical legacies of the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire, a number of economic disputes erupted between Russia and some neighbours, such as the 2006 Russian ban of Moldovan and Georgian wines. Moscow's policies under Putin towards these states were described as "efforts to bully democratic neighbors" by John McCain in 2007.[113]

In some cases, such as the Russia–Ukraine gas disputes, the economic conflicts affected other European countries, for example when a January 2009 gas dispute with Ukraine led state-controlled Russian company Gazprom to halt its deliveries of natural gas to Ukraine,[114] which left a number of European states, to which Ukraine transits Russian gas, to have serious shortages of natural gas in January 2009.[114] In an interview with the German historian Michael Stürmer about the Russian shut-down of gas to Ukraine in early 2005, Putin linked the shut-down to the Orange revolution, saying: "This has a price [the Orange revolution]. In spite of so much frustration we have stabilized the situation. In old days we concluded agreements with Ukraine year after year, and then included transit fees. The West Europeans had no idea that their energy security was a cliffhanger. By now we have a five-year agreement for transit to the E.U. This is an important step in the direction of European energy security".[8]

In 2009, the Russia–Ukraine dispute was resolved by a long-term agreement on price formula, agreed by Prime Ministers Vladimir Putin of Russia and Prime Minister of Ukraine Yulia Tymoshenko[114][115] (later, when the rising global oil prices prompted the rising gas prizes[116] the agreement turned very unfavourable for Ukraine; in October 2011 Tymoshenko was found guilty of abuse of office when brokering the 2009 deal and was sentenced to seven years in prison).[117]

The plans of Georgia and Ukraine to become members of NATO have caused some tensions between Russia and those states. In 2010, Ukraine did abandon these plans.[118] In public Putin has stated that Russia has no intention of annexing any country.[111]

Putin, in his relations with Russo-centric neighbor and former Soviet Republic Belarus, continued the general trend towards closer bi-lateral ties between the two countries, which has thus far stopped short of extending the depth of the Union of Russia and Belarus proposed and speculated by many media outlets both inside and outside Russia.[119]

_-_Crimea_disputed.svg.png)

In August 2008, Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili attempted to restore control over the breakaway South Ossetia, claiming this action was in response to Ossetian border attacks on Georgians and to alleged buildups of Russian non-peacekeeping forces. Russian "peacekeepers" fought alongside the South Ossetians as Georgian troops pushed into the province and seized most of the capital of Tskhinvali. However, the Georgian military was soon defeated in the resulting 2008 South Ossetia War after regular Russian forces entered South Ossetia and then Georgia proper, and also opened a second front in the other Georgian breakaway province of Abkhazia together with Abkhazian forces.[120][121] During this conflict, according to high level French diplomat Jean-David Levitte, Putin intended to depose the Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili and declared: "I am going to hang Saakashvili by the balls".[122]

Putin blamed the 2008 war and the bad relations between Russia and Georgia as "the result of the policy that the Georgian authorities conducted back then and still attempt to conduct now"; he stated that Georgia is a "brotherly nation that hopefully will finally understand that Russia is not an enemy, but is a friend and the relations will be restored"[123] (one month before Georgian President Saakashvili had stated "Putin has a problem with Georgian people, but not with Georgian government").[124] Putin stated in 2009 Georgia could have kept Abkhazia and South Ossetia "within its territory" if it had treated the residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia "with respect" (he claims they did "the opposite").[125]

During the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, Putin twice visited Ukraine before the election to show his support for Ukrainian Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, who was widely seen as a pro-Kremlin candidate, and he congratulated him on his anticipated victory before the official election returns had been in. Putin's personal support for Yanukovych was criticized as unwarranted interference in the affairs of a sovereign state (See also The Orange revolution). According to a document uncovered during the United States diplomatic cables leak Putin “implicitly challenged" the territorial integrity of Ukraine at the April 4, 2008, NATO-Russia Council Summit in Bucharest, Romania.[126]

The President of Ukraine elected during the Orange Revolution, Viktor Yushchenko, was succeeded in 2010 by Viktor Yanukovych, that led to improved relations with Russia.[127] Russia was able to expand the lease for the base for its Black Sea Fleet base in the Ukrainian city Sevastopol in exchange for lower gas prices for Ukraine (the 2010 Ukrainian–Russian Naval Base for Natural Gas treaty).[128] The President of Kyrgyzstan since 2009, Almazbek Atambayev, wants to guide Kyrgyzstan towards the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia and has stated his country has a "common future" with its neighbours and Russia.[129]

Despite existing or past tensions between Russia and most of the post-Soviet states, Putin has followed the policy of Eurasian integration. The Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia has already brought partial economic unity between the three states, and the proposed Eurasian Union is said to be a continuation of this customs union. Putin endorsed the idea of a Eurasion Union in 2011,[130][131][132][133] (the concept was proposed by the President of Kazakhstan in 1994).[134] On 18 November 2011, the presidents of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia signed an agreement, setting a target of establishing the Eurasian Union by 2015.[135] The agreement included the roadmap for the future integration and established the Eurasian Commission (modelled on the European Commission) and the Eurasian Economic Space, which started work on 1 January 2012.[135][136]

Intervention in Ukraine and annexation of Crimea

.jpeg)

As events came closer to crisis in Ukraine around February and March 2014, Putin answered the questions of reporters on this vital issue.[137] The residents of the province of Crimea decided in a referendum to ask for Russian protection on 16 March. On 18 March 2014 Putin made a well-publicized speech about the situation in Crimea.[138] Russia was excluded one week later from the G8 group as a result of its annexation of Crimea.[139]

Tensions in other ex-Soviet countries

Besides Ukraine, several other ex-Soviet and ex-communist countries continue to be flashpoints in the tug-of-war between the West and Russia.[140] Frozen conflicts in Georgia and Moldova have been major areas of dispute,[140][141] as both countries have breakaway regions that favor annexation by Russia.[142] The Baltic Sea and other areas have also caused tension between Russia and the West.[140][143] The Crimean crisis sparked new worries that Russia might try to further remake the borders of Eastern Europe.[144]

Georgia and the Caucasus

Since the mid-2000s, Georgia has sought closer relations with the West, while Russia has strongly opposed the expansion of Western institutions to its southern border. Georgia has a long connection with the Russian Federation, as it was a republic of the Soviet Union, and became part of the Russian Empire in 1801. In 2003, the Rose Revolution forced Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze to resign from office. Shevardnadze had been the leader of the Georgian Communist Party when Georgia was one of the republics of the Soviet Union, and Shevardnadze led Georgia for most of its first decade of independence.[145] Shevardnadze's successor, Mikheil Saakashvili, pursued closer relations with the West.[146] Under President George W. Bush, the United States sought to invite Ukraine and Georgia into NATO. However, Georgia's potential membership in NATO ran into opposition from other NATO members and Russia.[147][148] Partly in response to the potential expansion of NATO, Russia initiated the 2008 Russo-Georgian diplomatic crisis by lifting CIS sanctions on Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Though considered to be part of Georgia by the United Nations, Abkhazia and South Ossetia have both sought to secede from Georgia since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and both are strongly supported by Russia.[149] The Russo-Georgian War broke out in August 2008, as Georgia and Russia competed for influence in South Ossetia. Russia was strongly criticized by many Western countries for its part in the war, and the war heightened tensions between NATO and Russia.[147] The war ended with a unilateral Russian withdrawal of forces from parts of Georgia, but Russian forces continue to occupy parts of Georgia. In November 2014, a Russian-Abkhazian treaty was met with condemnation from Georgia and many Western countries, who feared that Russia might annex Abkhazia much like it annexed Crimea.[150] Georgia continues to pursue a policy of integration with the West.[151] Georgia holds a strategic position for the European Union, as it gives the EU access to oil in Azerbaijan and Central Asia without having to rely on Russian pipelines.[152]

Besides Georgia, the other two Caucasus states, Armenia and Azerbaijan, have also been a part of the rivalry between Russia and the West. The two countries are long-time rivals, and have a long-running dispute regarding control of Nagorno-Karabakh.[153] Armenia has close ties with Russia, while Azerbaijan has close ties to the United States and Turkey, both of which are members of NATO.[153] However, NATO also ties to Armenia, and both Armenia and Azerbaijan have been speculated as potential future members of NATO.[154] Armenia negotiated an Association Agreement with the European Union but, similar to Ukraine, Armenia chose to reject the deal in 2013.[155] The next year, Armenia voted to join the Eurasian Economic Union,[156] the Russian-backed free trade zone that seeks to rival the European Union.[157] However, Armenian leaders have also worked towards a free trade agreement with the EU.[156]

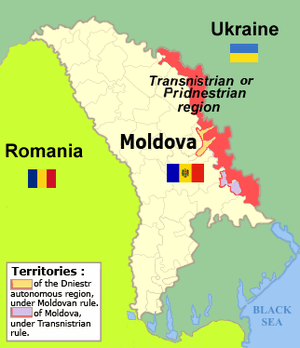

Moldova

Much like Ukraine, Moldova has experienced internal debates between those favoring closer ties to the West (including joining the European Union) and those favoring closer ties to Russia (including joining the Russian-backed Eurasian Union).[140] Also like Ukraine, Moldova was a part of the Soviet Union; though Moldova was a part of Romania prior to World War II, it was annexed into the Soviet Union in 1940. In May 2014, Moldova signed a major trade deal with the European Union,[152] causing Russia to apply pressure on the Moldovan economy, which relies heavily on remittances from Russia.[158] The 2014 Moldovan parliamentary elections saw a victory for an alliance of pro-Western integration parties.[140] Moldova is also home to a breakaway region, known as Transnistria, which forms the Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations along with Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno-Karabakh.[140] In 2014, Transnistria held a referendum in which it voted to join the Eurasian Economic Union,[140] and Russia has strong influence over the region.[149] A build-up of Russian forces on the Ukrainian-Russian border caused NATO commander Philip Breedlove to speculate that the Russian Federation might attempt to attack Moldova and occupy Transnistria.[159]

Baltic states and Scandinavia

The Baltic states of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia—all three of which are members of NATO—have warily watched Russian military movements and actions.[140][143] All three countries, within the Russian Empire prior to 1918, had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940 as part of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and Russian leaders were particularly distressed by their accession to NATO and the EU in 2004.[161] In 2014, the Baltic states reported several incursions into their air space by Russian military aircraft.[140] Tensions rose as Russian intelligence forces crossed the Estonian border and captured Estonian intelligence officer Eston Kohver.[143] In October 2014, Sweden engaged in a hunt for a foreign submarine that had entered its waters; suspicions that the submarine was Russian have caused further alarm in the Baltic states.[162] However, the Swedish Armed Forces later admitted that the alleged sighting of a Russian sub was actually just a "workboat".[163] The tensions in the Baltic and other areas have led neighboring Sweden and Finland, both of which have long been neutral states, to openly discuss joining NATO.[161]

In early April 2015, British press publications, with a reference to semi-official sources within the Russian military and intelligence establishment, suggested that Russia was ready to use any means—including nuclear weapons—to forestall NATO moving more forces into the Baltic states.[164][165]

Relations with Australia, Latin America, and others

Putin and his successor Medvedev have enjoyed warm relations with Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. Much of this has been through the sale of military equipment; since 2005, Venezuela has purchased more than $4 billion worth of arms from Russia.[166] In September 2008, Russia sent Tupolev Tu-160 bombers to Venezuela to carry out training flights.[167] In November 2008, both countries held a joint naval exercise in the Caribbean.[168] Earlier in 2000, Putin had re-established stronger ties with Fidel Castro's Cuba.

In September 2007, Putin visited Indonesia and in doing so became the first Russian leader to visit the country in more than 50 years.[169] In the same month, Putin also attended the APEC meeting held in Sydney, Australia where he met with Australian Prime Minister John Howard and signed a uranium trade deal. This was the first visit by a Russian president to Australia.

Energy policy

The Russian economy is heavily dependent on the export of natural resources such as oil and natural gas, and Russia has used these resources to its political advantage.[170][171] Meanwhile, the US and other Western countries have worked to lessen the dependency of Europe on Russia and its resources.[172] Starting in the mid-2000s, Russia and Ukraine had several disputes in which Russia threatened to cut off the supply of gas. As a great deal of Russia's gas is exported to Europe through the pipelines crossing Ukraine, those disputes affected several other European countries. Under Putin, special efforts were made to gain control over the European energy sector.[172] Russian influence played a major role in canceling the construction of the Nabucco pipeline, which would have supplied natural gas from Azerbaijan, in favor of South Stream (though South Stream itself was also later canceled).[63] Russia has also sought to create a Eurasian Economic Union consisting of itself and other post-Soviet countries.[173]

Like many other countries, Russia's economy suffered during the Great Recession. Following the Crimean Crisis, several countries (including most of NATO) imposed sanctions on Russia, hurting the Russian economy by cutting off access to capital.[174][175] At the same time, the global price of oil declined.[176] The combination of Western sanctions and the falling crude price in 2014 and thereafter, which was widely seen in Russia as a US–Saudi plot against it,[177] resulted in the ongoing 2014–15 Russian financial crisis.[176] As a way to get around Western sanctions, Russia and China signed a 150 billion yuan central bank liquidity swap line agreement to get around American sanctions.[178] and agreed to a US$400 billion deal which would supply natural gas to China over the next 30 years.

Notable foreign policy speeches by President Vladimir Putin

- Munich speech of Vladimir Putin on 10 February 2007

- Crimean speech of Vladimir Putin on 18 March 2014

- Valdai speech of Vladimir Putin on 24 October 2014

- Crimean speech on 4 December 2014[179]

- U.N. General Assembly speech on 28 September 2015[180]

General assessments by experts

Criticism

The British historian Max Hastings in 2007 described Putin as Stalin's "spiritual heir". He went on to argue that, "The notion of Western friendship with Russia is a dead letter, The best we can look for is grudging accommodation....We may hope that in the 21st century we shall not be obliged to fight Russia. But it would be foolish to suppose that we shall be able to lie beside this dangerous, emotional beast in safety or tranquility."[181]

The British academic Norman Stone in his 2007 article "No wonder they like Putin" compared Putin to General Charles de Gaulle.[182]

Commentary

Adi Ignatius in Time Magazine stated in 2007: "Putin... is not a Stalin. There are no mass purges in Russia today, no broad climate of terror. But Putin is reconstituting a strong state, and anyone who stands in his way will pay for it."[183]

Response to Criticism

In response to the general assessments by experts outside of Russia, press releases posted on an ongoing basis at The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, located in Switzerland, are available to read online.[184]

See also

References and notes

- Shuster, Simon. "The World According to Putin," Time September 16, 2013, pp. 30–35.

- Dmitri Trenin (March 4, 2014). "Welcome to Cold War II". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Mauldin, John (29 October 2014). "The Colder War Has Begun". Forbes. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Kendall, Bridget (12 November 2014). "Rhetoric hardens as fears mount of new Cold War". BBC News. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- America's Failed (Bi-Partisan) Russia Policy by Stephen F. Cohen, Huffington Post

- U.S. Withdrawal From the ABM Treaty

- Vladimir Poutine et son quart d’heure de gloire by André Liebich

- Stuermer, Michael (2008). Putin and the Rise of Russia. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 55, 57 & 192. ISBN 9780297855101. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- 43rd Munich Conference on Security Policy. Putin's speech in English Archived 2008-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, 10 February 2007.

- "Russia: Washington Reacts To Putin's Munich Speech". RFERL.

- Watson, Rob (10 February 2007). "Putin's speech: Back to cold war? Putin's speech: Back to cold war?". BBC.

- "United States Department of Defense". www.defenselink.mil. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Munich Conference on Security Policy: As Delivered by Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates, Munich, Germany, Sunday, February 11, 2007". United States Department of Defense. 2007-02-11. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- "Interview with Newspaper Journalists from G8 Member Countries". Presidential Administration of Russia. 2007-06-04. Archived from the original on 2008-05-04. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- Doug Sanders, "Putin threatens to target Europe with missiles" Archived 2008-12-31 at the Wayback Machine, The Globe and Mail, June 2, 2007

- Asymmetrical Iskander missile systems, RIA Novosti, November 15, 2007

- Press Conference following the end of the G8 Summit Archived 2008-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, June 8, 2007

- Annual Address to the Federal Assembly Archived 2008-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, April 26, 2007, Kremlin, Moscow

- Lavrov Announced Conditions of Resuming CFE Observance Archived 2008-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, December 3, 2007, Izvestia.ru

- "Russia walks away from CFE arms treaty". AFP via Yahoo! News. December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- "Russia Suspends Participation In CFE Treaty". Radio Liberty. December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- "US 'deeply regrets' Russia's 'wrong' decision on CFE". AFP. December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- "Putin poised to freeze arms pact as assertiveness grows". Financial Times. December 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- "Putin: supports for Kosovo unilateral independence "immoral, illegal"". Xinhua News Agency. 14 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- "Putin: Kosovo case terrible precedent". Press TV. 22 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- "EU's Solana rejects Putin's criticism over Kosovo's independence". IRNA. 23 February 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-02-26. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- Simpson, Emma (2006-01-16). "Merkel cools Berlin Moscow ties". BBC News. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Gonzalo Vina and Sebastian Alison (July 20, 2007). "Brown Defends Russian Expulsions, Decries Killings". Bloomberg News.

- "UK spied on Russia with fake rock". 27 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Russia suspends British Council regional offices". Reuters. December 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

- "Ukraine crisis: Nato suspends Russia co-operation". BBC News. Russia. 2014-04-02. Retrieved 2014-04-02.

- Putin, Vladimir V. (11 September 2013). "Opinion - What Putin Has to Say to Americans About Syria". Retrieved 27 September 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- Roth, Andrew (28 September 2015). "Live from New York: It's Putin Speech Bingo". Retrieved 27 September 2017 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- Ewen MacAskill (2014-11-09). "Close military encounters between Russia and the west 'at cold war levels'". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- "Russia Baltic military actions 'unprecedented' - Poland". BBC. UK. 2014-12-28. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- "Four RAF Typhoon jets head for Lithuania deployment". BBC. UK. 2014-04-28. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- "U.S. asks Vietnam to stop helping Russian bomber flights". Reuters. 2015-03-11. Retrieved 2015-04-12.

- "Russian Strategic Bombers To Continue Patrolling Missions". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

- "Russian INF Treaty Violations: Assessment and Response". csis.org. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Gordon, Michael R. (2014-07-28). "U.S. Says Russia Tested Cruise Missile, Violating Treaty". The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- "US and Russia in danger of returning to era of nuclear rivalry". The Guardian. UK. 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

- Gordon, Michael R. (2015-06-05). "U.S. Says Russia Failed to Correct Violation of Landmark 1987 Arms Control Deal". The New York Times. US. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- "Russia's deployed nuclear capacity overtakes US for first time since 2000". RT. Moscow. 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- Matthew Bodner (2014-10-03). "Russia Overtakes U.S. in Nuclear Warhead Deployment". The Moscow Times. Moscow. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad Archived 2016-01-23 at the Wayback Machine James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies: Monterey, CA. January 2014.

- Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (2014-09-21). "U.S. Ramping Up Major Renewal in Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 2015-01-05.

- "Russia's New Military Doctrine Hypes NATO Threat". www.worldpoliticsreview.com. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Putin signs new military doctrine naming NATO as Russia’s top military threat National Post, December 26, 2014.

- "US announces new tank and artillery deployment in Europe". UK: BBC. 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- "Nato shifts strategy in Europe to deal with Russia threat". UK: FT. 2015-06-23. Retrieved 2015-06-24.

- "Putin says Russia beefing up nuclear arsenal, NATO denounces 'saber-rattling'". Reuters. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России по итогам встречи министров обороны стран-членов НАТО the RF Foreign Ministry, 26 June 2015.

- "Russia says NATO build-up on its borders is to achieve 'dominance in Europe'". RT. 27 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Steven Pifer, Fiona Hill. "Putin’s Risky Game of Chicken", The New York Times, June 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- Steven Pifer. Putin’s nuclear saber-rattling: What is he compensating for? 17 June 2015.

- "Russian Program to Build World's Biggest Intercontinental Missile Delayed". The Moscow Times. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- MacFarquhar, Neil, "As Vladimir Putin Talks More Missiles and Might, Cost Tells Another Story", The New York Times, June 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- "Putin's war on the West". Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- Czuczka, Tony; Parkin, Brian (21 November 2014). "Merkel Bids to Stall Putin Influence at EU's Balkan Edge". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Kosovo precedent for 200 territories—Lavrov Archived 2008-02-26 at the Wayback Machine, Tanjug/B92, January 23, 2008

- "Putin's Reach: Merkel Concerned about Russian Influence in the Balkans". Spiegel. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "Far-Right Europe Has a Crush on Moscow". Moscow Times. 25 November 2014. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Yardley, Jim; Becker, Jo (30 December 2014). "How Putin Forged a Pipeline Deal That Derailed". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- "From cold war to hot war". Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "In the Kremlin's pocket". Economist. 14 February 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Hungarian protesters hit out at Orban's 'move towards Russia'". Yahoo News. 2 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Traynor, Ian (17 November 2014). "European leaders fear growth of Russian influence abroad". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- "Poland to build Russia border towers at Kaliningrad". BBC. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- "Poland border watchtowers 'planned'". The Independent. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- "Kaliningrad: European fears over Russian missiles". BBC. 16 December 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Roth, Andrew (16 December 2013). "Deployment of Missiles Is Confirmed by Russia". New York Times. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- "REFILE-Poland and U.S. Army hold joint air defence exercises near Warsaw". 21 March 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2017 – via Reuters.

- "Prime Minister Đukanović: Protests in Podgorica supported by circles around Serbian Ortodox Church, and Russia". www.gov.me. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Sputnik. "Montenegro Leader Accuses Russia of Supporting Opposition in His Country". sputniknews.com. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Vladimir Putin (2012-12-24). "For Russia, deepening friendship with India is a top foreign policy priority by President Vladimir Putin". The Hindu. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- "India, Russia sign new defence deals: BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. 2012-12-24. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Rajeev Sharma, specially for RIR (2012-12-24). "13th Indo-Russian Summit reaffirms time-tested ties: Russia & India Report". Indrus.in. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- India has right to join SCO, not Pakistan: Russian envoy – News Archived April 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Russia supports India's membership in NSG". Business Standard. 2012-06-21. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- India and APEC: Centre of Mutual Gravitation: International Affairs Archived September 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Russia keen to join SAARC as observer: Oneindia News". News.oneindia.in. 2006-11-22. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- "SAARC The Changing Dimensions: UNU-CRIS Working Papers United Nations University - Comparative Regional Integration Studies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Rajeev Sharma, specially for RIR (2012-11-28). "Top Indian diplomat explains Russia's importance to India: Russia & India Report". Indrus.in. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Page, Jeremy (26 September 2010). "Russian Oil Route Will Open to China". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Press Statement and Responses to Media Questions following the Peace Mission 2007 Counterterrorism Exercises and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Summit". Presidential Administration of Russia. 2007-08-17. Archived from the original on 2008-05-31. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- "Russia restores Soviet-era strategic bomber patrols". RiaNovosti. 2007-08-17. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- SCO Scares NATO Archived 2012-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, August 8, 2007, KM.ru

- Russia Over Three Oceans Archived 2012-02-08 at the Wayback Machine, August 20, 2007, "Chas", Latvia

- Beginning of Meeting with Defense Minister Anatoliy Serdyukov Archived June 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, December 5, 2007, Kremlin.ru

- Guy Faulconbridge. Russian navy to start sorties in Mediterranean Reuters December 5, 2007.

- Russia's Navy Has Resumed Presence in World Ocean Vzglyad.ru (Russian) December 5, 2007.

- Павел Фельгенгауэр. Семь честных слов под килем Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine Novaya Gazeta № 95 December 13, 2007.

- Osborn, Andrew (2017-10-04). "Russia quietly throws North Korea lifeline in bid to stymie regime change". The Japan Times Online. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

- "Russia Provides New Internet Connection to North Korea | 38 North: Informed Analysis of North Korea". 38 North. 2017-10-01. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

- DeYoung, Karen; Nakashima, Ellen; Rauhala, Emily (2017-09-30). "Trump signed presidential directive ordering actions to pressure North Korea". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

- Putin: Iran Has Right to Develop Peaceful Nuclear Programme, 16 October 2007, Rbc.ru

- "Putin's warning to the U.S." Reuters. 16 October 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007.

- Putin Positive on Second Caspian Summit Results, Meets With Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad Archived May 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 16 October 2007, Kremlin.ru

- Visit to Iran. Second Caspian Summit Archived 2008-05-04 at the Wayback Machine, 15–16 October 2007, Kremlin.ru

- Vladimir Putin defies assassination threats to make historic visit to Tehran, 16 October 2007, The Times.

- Answer to a Question at the Joint Press Conference Following the Second Caspian Summit Archived May 4, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, 16 October 2007, Tehran, Kremlin.ru

- "Putin's visit 'historic and strategic'". gulfnews. 2008-04-18. Archived from the original on 2013-05-14. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Parks, Cara (21 March 2011). "Putin: Military Intervention In Libya Resembles 'Crusades'". Huffington Post.

- "Putin states the West has no legal right to execute Gaddafi — RT". Rt.com. 2011-04-26. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- "Vladimir Putin Blames US Drones For Gaddafi Death, Slams John McCain". Mediaite. 2011-12-15. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Citizen, Ottawa (2011-12-16). "Putin claims U.S. planned murder of Gadhafi". Canada.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-20. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Trenin, Dmitri (9 February 2012). "Why Russia Supports Assad". The New York Times.

- Fred Weir (2012-01-19). "Why Russia is willing to sell arms to Syria". CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Viscusi, Gregory (2012-06-01). "Hollande Clashes With Putin Over Ouster of Syria's Assad". Businessweek. Retrieved 2013-06-22.

- Putin, Vladimir V. (11 September 2013). "A Plea for Caution From Russia". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Polish head rejects Putin attack, BBC News (24 December 2004)

- Putin calls 'color revolutions' an instrument of destabilization, Kyiv Post (15 December 2011)

- McCain, John (November/December 2007, Vol 86, Number 6). "An Enduring Peace Built on Freedom // Revitalizing the Transatlantic Partnership". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2008-02-06. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Q&A: Russia-Ukraine gas row, BBC News (20 January 2009).

- Russia opens gas taps to Europe, BBC News (20 January 2009)

- "Natural gas, Europe price chart". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Ukraine ex-PM Yulia Tymoshenko jailed over gas deal, BBC News (11 October 2011)

- Ukraine's parliament votes to abandon Nato ambitions, BBC News (3 June 2010)

- "Putin eyes full merger with Belarus", December 10, 2007.

- "Russia and Eurasia". Heritage.org. Archived from the original on 25 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- "Day-by-day: Georgia-Russia crisis". BBC News. 21 August 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-10.

- https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/3454154/Vladimir-Putin-threatened-to-hang-Georgia-leader-by-the-balls.html

- Putin warns US against rearming Georgia, RT (22 February 2012)

- Georgia’s Saakashvili Slams Putin for Nationalist Comment, RIA Novosti (21 January 2012)

- Putin on Georgia's territorial integrity, RT via YouTube (8 Augustus 2009)

- After Russian invasion of Georgia, Putin's words stir fears about Ukraine. Kyiv Post (November 30, 2010)

- "World Report 2011: Ukraine". 24 January 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Russia, Ukraine agree on naval-base-for-gas deal, CNN (21 April 2010)

- "Kyrgyzstan profile". 30 July 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2017 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- New Integration Project for Eurasia – A Future That Is Being Born Today, Izvestiya (October 3, 2011)

- Новый интеграционный проект для Евразии – будущее, которое рождается сегодня (in Russian)

- Bryanski, Gleb (3 October 2011). "Russia's Putin says wants to build "Eurasian Union"". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Новый интеграционный проект для Евразии – будущее, которое рождается сегодня. Izvestia (in Russian). 3 October 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Kilner, James (6 October 2011). "Kazakhstan welcomes Putin's Eurasian Union concept". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- "Russia sees union with Belarus and Kazakhstan by 2015". BBC News. 18 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Евразийские комиссары получат статус федеральных министров (in Russian). Tut.By. 17 November 2011. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- "Vladimir Putin answered journalists' questions on the situation in Ukraine". Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Putin, Vladimir. "Address by President of the Russian Federation", Kremlin Web Site (18 March 2014).

- U.S., other powers kick Russia out of G8, CNN

- Mackinnon, Mark (1 December 2014). "The new Cold War: Pro-Russian influence extends beyond Ukraine". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Oliphant, Roland (18 November 2014). "Merkel fears construction of Cold-War zones across Europe if Russia not given hard counter in Ukraine". National Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Toal, Gerard; O'Loughlin, John (20 March 2014). "How people in South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria feel about annexation by Russia". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Higgins, Andrew (5 October 2014). "Tensions Surge in Estonia Amid a Russian Replay of Cold War Tactics". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Penhaul, Karl (11 April 2014). "To Russia with love? Transnistria, a territory caught in a time warp". CNN. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Martin, Douglas (7 July 2014). "Eduard Shevardnadze, Foreign Minister Under Gorbachev, Dies at 86". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- de Waal, Thomas (29 October 2013). "So Long, Saakashvili". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Peter, Laurence (2 September 2014). "Why Nato-Russia relations soured before Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- "Bush urging Nato expansion east". BBC News. 2 April 2008. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Herszenhorn, David (24 November 2014). "Pact Tightens Russian Ties With Abkhazia". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- McLaughlin, Daniel (25 November 2014). "West backs Georgia as Russia stokes new annexation fears". Irish Times. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Dreazen, Yochi (26 February 2014). "Look West, Young Man: Georgia's 31-Year-Old Prime Minister Turns To Europe, Not Russia". Foreign Policy.com. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Peter, Laurence (27 June 2014). "Guide to the EU deals with Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine". BBC News. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Khojoyan, Sarah (4 August 2014). "New War Risk on Russian Fringe Amid Armenia-Azeri Clashes". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Paterson, Tony (1 April 2014). "Ukraine crisis: Nato 'to step up military cooperation with Russia's neighbours'". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Traynor, Ian (21 November 2013). "Ukraine suspends talks on EU trade pact as Putin wins tug of war". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Herszenhorn, David (10 December 2014). "Armenia Wins Backing to Join Trade Bloc Championed by Putin". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- "The Other EU". The Economist. 23 August 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Ciochina, Simon (21 December 2014). "Moldovan migrants denied re-entry to Russia". DeutscheWelle. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- Morello, Carol; DeYoung, Karen (24 March 2014). "NATO general warns of further Russian aggression". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- "UNIAN News. Latest news of Ukraine and world". uatoday.tv. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Scrutton, Alistair; Johnson, Simon (20 October 2014). "Swedish 'Cold War' thriller exposes Baltic Sea nerves over Russia". Reuters. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- Ritter, Karl; Huuhtanen, Matti (20 October 2014). "Submarine hunt sends Cold War chill across Baltic". Washington Post. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- "'Submarine' in Sweden was only civilian boat". 2015-04-13. Retrieved 2016-09-26.

- Johnston, Ian (2 April 2015). "Russia threatens to use 'nuclear force' over Crimea and the Baltic states". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "Putin threat of nuclear showdown over Baltics". The Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Russia forges nuclear links with Venezuela Archived 2013-11-10 at the Wayback Machine france24.com

- "Russian bombers land in Venezuela". 11 September 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2017 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- http://www.itar-tass.com/eng/level2.html?NewsID=13111604&PageNum=0. Retrieved October 19, 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Russia Courts Indonesia". 12 October 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- Finn, Peter (2007-11-03). "Russia's State-Controlled Gas Firm Announces Plan to Double Price for Georgia". Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-12-25.

- Matthews, Owen (2014-09-24). "Putin's 'Last and Best Weapon' Against Europe: Gas". Retrieved 2015-01-03.

- Klapper, Bradley (3 February 2015). "New Cold War: US, Russia fight over Europe's energy future". Associated Press. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Neyfakh, Leon (9 March 2014). "Putin's long game? Meet the Eurasian Union". Boston Globe. Retrieved 21 January 2015.

- Stewart, James (7 March 2014). "Why Russia Can't Afford Another Cold War". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Chiara Albanese and Ben Edwards (9 October 2014). "Russian Companies Clamor for Dollars to Repay Debt". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- Chung, Frank (18 December 2014). "The Cold War is back, and colder". News.au. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- "Oil Plunge Part of US Campaign to Destabilize Russia". Russia Insider. 21 November 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- Smolchenko, Anna (13 October 2014). "China, Russia seek 'international justice', agree currency swap line". Yahoo! News. AFP. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- "Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly". The Kremlin, Moscow, Russia. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- "70th Session of the United Nations General Assembly". The Kremlin, Moscow, Russia. 28 September 2015. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Liel Leibovitz, "Standing Up to Putin" Tablet April 19, 2012.

- Stone, Norman (4 December 2007). "No Wonder They Like Putin". The Sunday Times, UK. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- Ignatius, Adi (2007-12-19). "A Tsar Is Born - Person of the Year 2007". Time, USA. Retrieved 2010-08-02.

- "The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Switzerland". The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Switzerland. 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Further reading

- Ambrosio, Thomas, and Geoffrey Vandrovec. "Mapping the Geopolitics of the Russian Federation: The Federal Assembly Addresses of Putin and Medvedev." Geopolitics (2013) 18#2 pp 435–466.

- Gvosdev, Nikolas K., and Christopher Marsh. Russian Foreign Policy: Interests, Vectors, and Sectors (Washington: CQ Press, 2013) excerpt and text search

- Kanet, Roger E. Russian foreign policy in the 21st century (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

- Larson, Deborah Welch, and Alexei Shevchenko. "Status seekers: Chinese and Russian responses to US primacy." International Security (2010) 34#4 pp 63–95.

- Legvold, Robert, ed. Russian Foreign Policy in the 21st Century and the Shadow of the Past (2007).

- Mankoff, Jeffrey. Russian Foreign Policy: The Return of Great Power Politics (2nd ed. 2011).

- Myers, Steven Lee. The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin (2015)

- Schoen, Douglas E. and Melik Kaylan. Return to Winter: Russia, China, and the New Cold War Against America (2015)

- Stent, Angela E. The Limits of Partnership: U.S. Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton UP, 2014) 355 pages; excerpt and text search

- Tsygankov, Andrei P. "The Russia-NATO mistrust: Ethnophobia and the double expansion to contain “the Russian Bear”." Communist and Post-Communist Studies (2013).

External links

- H. Ellyatt (March 1, 2018). "Putin reveals new Russian missile that can 'reach any point in the world". Moscow: CNBC.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

Putin joked that the two new strategic nuclear weapons he described — the global cruise missile and the subsurface unmanned vehicle — did not have names yet,[...] and new system capable of destroying intercontinental targets with hypersonic speed and high-precision, able to maneuver both in terms of its course and altitude.

.jpg)

.jpg)