Saurischia

Saurischia (/sɔːˈrɪskiə/ saw-RIS-kee-ə, meaning "reptile-hipped" from the Greek sauros (σαῦρος) meaning 'lizard' and ischion (ἴσχιον) meaning 'hip joint')[1] is one of the two basic divisions of dinosaurs (the other being Ornithischia). In 1888, Harry Seeley classified dinosaurs into two orders, based on their hip structure,[2] though today most paleontologists classify Saurischia as an unranked clade rather than an order.[3]

| Saurischians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Herrerasaurus (large), Eoraptor (small), and Plateosaurus (skull), three early saurischians | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia Seeley, 1888 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Description

All carnivorous dinosaurs (certain types of theropods) are traditionally classified as saurischians, as are all of the birds and one of the two primary lineages of herbivorous dinosaurs, the sauropodomorphs. At the end of the Cretaceous Period, all saurischians except the birds became extinct in the course of the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. Birds, as direct descendants of one group of theropod dinosaurs, are a sub-clade of saurischian dinosaurs in phylogenetic classification.[4]

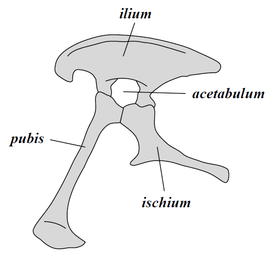

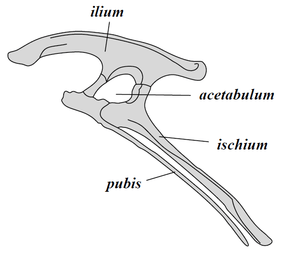

Saurischian dinosaurs are traditionally distinguished from ornithischian dinosaurs by their three-pronged pelvic structure, with the pubis pointed forward. The ornithischians' pelvis is arranged with the pubis rotated backward, parallel with the ischium, often also with a forward-pointing process, giving a four-pronged structure. The saurischian hip structure led Seeley to name them "lizard-hipped" dinosaurs, because they retained the ancestral hip anatomy also found in modern lizards and other reptiles. He named ornithischians "bird-hipped" dinosaurs because their hip arrangement was superficially similar to that of birds, though he did not propose any specific relationship between ornithischians and birds. However, in the view which has long been held, this "bird-hipped" arrangement evolved several times independently in dinosaurs, first in the ornithischians, then in the lineage of saurischians including birds (Avialae), and lastly in the therizinosaurians. This would then be an example of convergent evolution, avialans, therizinosaurians, and ornithischian dinosaurs all developed a similar hip anatomy independently of each other, possibly as an adaptation to their herbivorous or omnivorous diets.[5]

Classification

Saurischian pelvis structure (left side)

Saurischian pelvis structure (left side) Tyrannosaurus pelvis (showing saurischian structure – left side)

Tyrannosaurus pelvis (showing saurischian structure – left side) Ornithischian pelvis structure (left side)

Ornithischian pelvis structure (left side) Edmontosaurus pelvis (showing ornithischian structure – left side)

Edmontosaurus pelvis (showing ornithischian structure – left side)

In his paper naming the two groups, Seeley reviewed previous classification schemes put forth by other paleontologists to divide up the traditional order Dinosauria. He preferred one that had been put forward by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, which divided dinosaurs into four orders: Sauropoda, Theropoda, Ornithopoda, and Stegosauria (these names are still used today in much the same way to refer to suborders or clades within Saurischia and Ornithischia).[2]

Seeley, however, wanted to formulate a classification that would take into account a single primary difference between major dinosaurian groups based on a characteristic that also differentiated them from other reptiles. He found this in the configuration of the hip bones, and found that all four of Marsh's orders could be divided neatly into two major groups based on this feature. He placed the Stegosauria and Ornithopoda in the Ornithischia, and the Theropoda and Sauropoda in the Saurischia. Furthermore, Seeley used this major difference in the hip bones, along with many other noted differences between the two groups, to argue that "dinosaurs" were not a natural grouping at all, but rather two distinct orders that had arisen independently from more primitive archosaurs.[2] This concept that "dinosaur" was an outdated term for two distinct orders lasted many decades in the scientific and popular literature, and it was not until the 1960s that scientists began to again consider the possibility that saurischians and ornithischians were more closely related to each other than they were to other archosaurs.

Although his concept of a polyphyletic Dinosauria is no longer accepted by most paleontologists, Seeley's basic division of the two dinosaurian groups has stood the test of time, and has been supported by modern cladistic analysis of relationships among dinosaurs.[6] A node-base clade, Eusaurischia, was named for the least inclusive group containing sauropodomorphs (represented by Cetiosaurus) and theropods (represented by Neornithes). Any saurischian that diverged before the theropod-sauropodomorph split is therefore outside clade Eusaurischia.[7]

One alternative hypothesis challenging Seeley's classification was proposed by Robert T. Bakker in his 1986 book The Dinosaur Heresies. Bakker's classification separated the theropods into their own group and placed the two groups of herbivorous dinosaurs (the sauropodomorphs and ornithischians) together in a separate group he named the Phytodinosauria ("plant dinosaurs").[8] The Phytodinosauria hypothesis was based partly on the supposed link between ornithischians and prosauropods, and the idea that the former had evolved directly from the latter, possibly by way of an enigmatic family that seemed to possess characters of both groups, the segnosaurs.[9] However, it was later found that segnosaurs were an unusual type of herbivorous theropod saurischian closely related to birds, and the Phytodinosauria hypothesis fell out of favor.

A 2017 study by Dr Matthew Grant Baron, Dr David B. Norman and Prof. Paul M. Barrett did not find support for a monophyletic Saurischia, according to its traditional definition. Instead, the group was found to be paraphyletic, with Theropoda removed from the group and placed as the sister group to the Ornithischia in the newly defined clade Ornithoscelida. As a result, the authors redefined Saurischia as "the most inclusive clade that contains D. carnegii, but not T. horridus", resulting in a clade containing only the Sauropodomorpha and Herrerasauridae.[10][11]

See also

References

- Oxford English Dictionary

- Seeley, H.G. (1888). "On the classification of the fossil animals commonly named Dinosauria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 43 (258–265): 165–171. doi:10.1098/rspl.1887.0117.

- Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., and Osmólska, H. (eds.). (2004). The Dinosauria. 2nd edition. University of California Press, Berkeley. 833 pp.

- Padian, K. (2004). "Basal Avialae". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 210–231. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Zanno, L. E.; Gillette, D. D.; Albright, L. B.; Titus, A. L. (2009). "A new North American therizinosaurid and the role of herbivory in 'predatory' dinosaur evolution". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1672): 3505–11. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1029. PMC 2817200. PMID 19605396.

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.) (2004). The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press., 861 pp.

- Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P., & Osmólska, H. (Eds.). (2007). The dinosauria. Univ of California Press.

- Bakker, R. T. (1986). The Dinosaur Heresies. New York: William Morrow. p. 203. ISBN 0-14-010055-5.

- Paul, G.S. (1988). Predatory Dinosaurs of the World, a Complete Illustrated Guide. New York: Simon & Schuster. 464 p.

- Baron, M.G., Norman, D.B., and Barrett, P.M. (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution". Nature, 543: 501–506. doi:10.1038/nature21700.

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/new-study-shakes-the-roots-of-the-dinosaur-family-tree