Emydidae

Emydidae is a family of testudines (turtles) which includes close to 50 species in 10 genera.[3][4] Members of this family are commonly called terrapins, pond turtles, or marsh turtles.[1] Several species of Asian box turtle were formerly classified in the family; however, revised taxonomy has separated them to a different family (Geoemydidae). As currently defined, Emydidae is entirely a Western Hemisphere family, with the exception of two species of pond turtle.

| Emydidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Black-knobbed map turtle | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae (Rafinesque, 1815)[2] |

| Subfamilies and genera | |

| Synonyms [2] | |

| |

Description

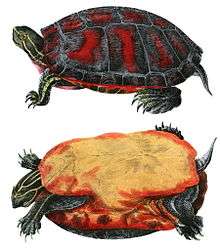

The upper shell (carapace) of most emydids is the shape of a low arch, although in some species, it is domed. The upper shell may have one or two ridges that run from front to the back of the animal (a projection commonly called a "keel"), or such a feature may be absent. A prominent bridge often connects the top shell to the bottom shell (plastron). Emydids have large bottom shells, and some members of the family have a movable hinge that separates pectoral and abdominal segments (scutes). The skull is small.[1]

The limbs of these turtles are adapted for swimming, with every member having some level of toe webbing.[1]

Behavior

Food habits range from strictly carnivorous to strictly herbivorous. The carnivores feed on annelids, crustaceans, and fish. In several species, a shift from carnivory in juveniles to herbivory in adults occurs. Small mammals, especially raccoons, are responsible for the destruction of many emydid nests. The wide range of sizes in mature animals leads to an assortment of predators. While snapping turtles are responsible for predation in some smaller species (e.g., Glyptemys muhlenbergii), they cannot eat larger species. Alligators pose a risk to adults of several species.

Knowledge of reproductive behavior ranges from some of the most detailed, long-term study of any taxon (Chrysemys picta in Michigan) to a total lack of information. In many species, dimorphisms include elongated foreclaws or a concave plastron in the male. The longer claws are used in a courtship routine in which the male faces the female and fans her face. The concave plastron allows the male to mount females in species with more domed carapaces (e.g., Terrapene). Reproduction is on an annual cycle, and multiple clutches may be produced in a single season. Clutch size is quite variable, ranging from as few as two to more than 30 eggs.

Threats

Emydids are the turtles most commonly sold through the pet trade. The pond slider (Trachemys scripta) has expanded its range through the careless release of pets into the wild. Many Asian species are threatened by over-collection of animals for sale in markets and into the pet trade. The North American species Clemmys muhlenbergii is listed as an Appendix II species by CITES and is considered threatened or endangered in many states. This status is the result of habitat degradation and over-collection.

Systematics and evolution

The Emydidae are most closely related to the tortoises (Testudinidae) and are included along with that family in the Testudinoidea. Shared features include a lack of inframarginal scutes, the shape and muscle attachment of the ilium, and the shape of the eighth cervical vertebra (biconvex). Within the Emydidae, two subfamilies were recognized along biogeographic lines. The Emydidae as understood today contain New World species (except Emys), while the former Batagurinae, today a separate family Geoemydidae, contain Old World species (except Rhinoclemmys). Osteological characters, such as the construction of the mandible and articulations of the cervical vertebrae distinguish the two families.

The enigmatic big-headed turtle (Platysternon megacephalum) was for some time considered a specialized but still very primitive early offshoot of the Emydidae. With the Geoemydidae being split off, though, it is better reinstated as its own family Platysternidae, though it seems very close to the emydid-geoemydid group.

Fossil record

Presumed emydids are well represented in the fossil record. Gyremys sectabilis and Clemmys backmani are both North American species that date from the Upper Cretaceous and Paleocene, respectively. These are the two oldest fossil species. Many other extinct species traditionally placed in the Emydidae are known from the Eocene of North America, Asia, and Europe, but the Old World taxa are likely to be more properly Geoemydidae. The North American genus Palaeochelys and probably the trans-Atlantic Echmatemys, too, would seem to be Emydidae, but their precise relationships to the living genera are indeterminate.

Classification

The two subfamilies and genera are arranged as follows:[3]

- Subfamily Emydinae

- Subfamily Deirochelyinae

- Genus Chrysemys

- Genus Deirochelys

- Genus Graptemys

- Genus Malaclemys

- Genus Pseudemys

- Genus Trachemys

- Classified subfamily

- Genus Psilosemys sp. Psilosemys wyomingensis[6]

References

- Ernst 1994, p. 203

- Rhodin 2010, p. 000.99

- Rhodin 2010, pp. 000.99-000.107

- EMYSystem Family Page: Emydidae (Pond Turtles)

- James E. Martin; V. Standish Mallory (2011). "Vertebrate paleontology of the late Miocene (Hemphillian) Wilbur Locality of central Washington". Paludicola. 8 (3): 155–185.

- J. Howard Hutchison (2013). "New turtles from the Paleogene of North America". In Donald B. Brinkman; Patricia A. Holroyd; James D. Gardner (eds.). Morphology and Evolution of Turtles. Springer. pp. 477–497. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4309-0_26. ISBN 978-94-007-4308-3.

- Bibliography

- Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger William; Lovich, Jeffery E. (1994). Dutro, Nancy P. (ed.). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 203–204. ISBN 1-56098-346-9.

- Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Iverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the World 2010 Update: Annotated Checklist of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution and Conservation Status" (PDF). pp. 000.89–000.138. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2010-12-15. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

Further reading

- Seidel, Michael E.; Ernst, Carl H. (2017). "A Systematic Review of the Turtle Family Emydidae". Vertebrate Zoology 67 (1): 1-122.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Emydidae |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emydidae. |