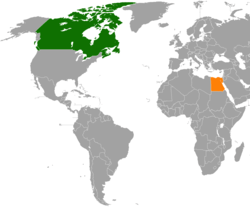

Canada–Egypt relations

Canadian-Egyptian relations are foreign relations between Canada and Egypt. Both countries established embassies in their respective capitals in 1954. Canada has an embassy in Cairo. Egypt has an embassy in Ottawa and a Consulate-General in Montreal. Though both had been part of the British Empire, only Canada is part of the Commonwealth, Egypt is not.

| |

Canada |

Egypt |

|---|---|

History

Canada and Egypt first established diplomatic ties in 1954 after the Egyptian Revolution of 1952 and the abdication of the Egyptian monarchy, thus creating the Republic of Egypt under President Jamal Abdel Nasser.[1] They both established embassies in their respective capitals, a Canadian one in Cairo and with the Egyptian Embassy located in Ottawa. The two countries enjoyed good relations, but did not take prominence to one another until Canada intervened in The Suez Crisis of 1956 when Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal and in response France, The United Kingdom and Israel took military actions against Egypt.[2]

Canada decried the actions taken by France, the UK and Israel against Egypt and after the end of hostilities the Canadian Minister of External Affairs Lester B. Pearson proposed that the United Nations create a United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF), whose mission was to enter Egyptian territory and act as a buffer between Egyptian forces and Israeli forces in occupied territory.[3] Canada pledged a substantial number of troops to the UNEF mission. On May 16, 1967 Egypt ordered all UNEF forces out of Egyptian territory, and most had retreated before the beginning of the Six-Day War.[4]

2010–2012

Canada provides aid to Egypt. Official development assistance (ODA) from Canada to Egypt is estimated 17m US dollars in 2010-2011. Aid has been targeted at micro-finance, helping private sector growth in small enterprises, funding for apprenticeships, training, and literacy.[5]

2013 Revolution

The Canadian government was amongst those to use the word "coup"[6] to describe the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi by the Egyptian military. In the weeks following the revolution, however, the Canadian government did not further question the legitimacy of the new regime and instead issued generic calls for peace and dialog and took a "wait and see" approach.[7]

References

- Hilliker, John; Barry, Donald (1995). Canada's Department of External Affairs: Coming of Age, 1946-1968. (Institute of Public Administration of Canada) McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-7735-0738-8. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- Hillmer, Norman (1999). Pearson: the unlikely gladiator. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-7735-1768-5.

- Chandra, Satish; Chandra, Mala (2006). International conflicts and peace making process: role of the United Nations (1st ed.). Mittal Publications. p. 29. ISBN 978-81-8324-166-3. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- "Canada-Egypt Relations". Government of Canada. 2010-06-11. Archived from the original on 2011-02-01. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- "Canada's development assistance in Egypt". Acdi-cida.gc.ca. 2016-08-16. Archived from the original on 2014-03-05. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "Canada Calls for Calm after Egyptian Coup". International.gc.ca. 2013-07-05. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "Egyptian ambassador lauds 'prudent' diplomatic stance by Canada in wake of coup | National Post". News.nationalpost.com. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

External links

- Canada-Egypt Relations - Government of Canada

- Canadian embassy in Cairo - Government of Canada

- Embassy of Canada to Egypt Verified Government Page on FB

.svg.png)