Dinosauromorpha

Dinosauromorpha is a clade of avemetatarsalian archosaurs (reptiles closer to birds than to crocodilians) that includes the Dinosauria (dinosaurs) and some of their close relatives. It was originally defined to include dinosauriforms and lagerpetids,[1] with later formulations specifically excluding pterosaurs from the group.[2] Birds are the only dinosauromorphs which survive to the present day.

| Dinosauromorphs | |

|---|---|

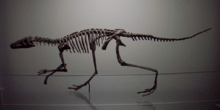

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton of a Lagosuchus talampayensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Ornithodira |

| Clade: | Dinosauromorpha Benton, 1985 |

| Subgroups | |

Definition

The name "Dinosauromorpha" was briefly coined by Michael J. Benton in 1985.[3] It was considered an alternative name for the group "Ornithosuchia", which was named by Jacques Gauthier to correspond to archosaurs closer to dinosaurs than to crocodilians.[4] Although "Ornithosuchia" was later recognized as a misnomer (since ornithosuchids are now considered closer to crocodilians than to dinosaurs), it was still a more popular term than Dinosauromorpha in the 1980s.[1] The group encompassed by Gauthier's "Ornithosuchia" and Benton's "Dinosauromorpha" is now given the name Avemetatarsalia.[2]

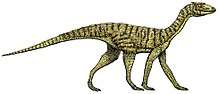

In 1991, Paul Sereno popularized the group, and defined it as a node-based clade, defined by a last common ancestor and its descendants. In his definition, Dinosauromorpha included the last common ancestor of Lagerpeton (a lagerpetid), Marasuchus (a possible synonym of Lagosuchus) Pseudolagosuchus (now considered a synonym of the silesaurid Lewisuchus), Dinosauria (including Aves), and all its descendants. This definition was intended to correspond to a clade including dinosauriforms and lagerpetids, but not pterosaurs or other archosaurs.[1][5]

In 2011, Dinosauromorpha was redefined by Sterling Nesbitt to be a branch-based clade, defined by including reptiles closer to one group than to another. Under this definition, Dinosauromorpha included all reptiles closer to dinosaurs (represented by Passer domesticus, the house sparrow), rather than pterosaurs (represented by Pterodactylus), ornithosuchids (represented by Ornithosuchus), or other pseudosuchians (represented by Crocodylus niloticus, the Nile crocodile). Nesbitt's study supported the hypothesis that Pterosauromorpha (pterosaurs and their potential relatives) was the sister group of Dinosauromorpha. Pterosauromorphs and dinosauromorphs together formed the group Ornithodira, which encompasses almost all avemetatarsalians.[2]

Origins

Dinosauromorphs appeared by the Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic around 242 to 244 million years ago, splitting from other ornithodires. Early Triassic footprints reported in October 2010 from the Świętokrzyskie (Holy Cross) Mountains of Poland may belong to a dinosauromorph. If so, the origin of dinosauromorphs would be pushed back into the Early Olenekian, around 249 Ma. The oldest Polish footprints are from a small quadrupedal animal named Prorotodactylus, but footprints belonging to the ichnogenus Sphingopus that have been found from Early Anisian strata show that moderately large bipedal dinosauromorphs had appeared by 246 Ma. The tracks show that the dinosaur lineage appeared soon after the Permian-Triassic extinction event. Their age suggests that the rise of dinosaurs was slow and drawn out across much of the Triassic.[6]

Basal forms include Saltopus,[7][8] Marasuchus, the perhaps identical Lagosuchus, the lagerpetid Lagerpeton from the Ladinian of Argentina and Dromomeron from the Norian of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas (all in the United States), Ixalerpeton polesinensis and an unnamed form from the Carnian (Santa Maria Formation) of Brazil,[9][10] and the silesaurids, which include Silesaurus from the Carnian of Poland, Eucoelophysis from the Carnian-Norian of New Mexico, Lewisuchus and the perhaps identical Pseudolagosuchus from the Ladinian of Argentina,[11][12] Sacisaurus from the Norian of Brazil,[13] Technosaurus from the Carnian of Texas,[14] Asilisaurus from the Anisian of Tanzania,[15] and Diodorus from the Carnian(?) to Norian of Morocco.[16]

Phylogeny

Cladogram simplified after Nesbitt (2011):

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Sereno, Paul C. (1991-12-31). "Basal Archosaurs: Phylogenetic Relationships and Functional Implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (sup004): 1–53. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011426. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The early evolution of archosaurs: relationships and the origin of major clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 1–292. doi:10.1206/352.1. hdl:2246/6112.

- Benton, Michael J. (1985-06-01). "Classification and phylogeny of the diapsid reptiles". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 84 (2): 97–164. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1985.tb01796.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- Gauthier, J.A. (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". In Padian, K. (ed.). The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 8. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences. pp. 1–55.

- Langer, M. C.; Nesbitt, S. J.; Bittencourt, J. S.; Irmis, R. B. (2013). "Non-dinosaurian Dinosauromorpha" (PDF). Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 379: 157–186. doi:10.1144/SP379.9.

- Brusatte, S.L.; Niedźwiedzki, G.; Butler, R.J. (2010). "Footprints pull origin and diversification of dinosaur stem lineage deep into Early Triassic". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 278 (1708): 1107–1113. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1746. PMC 3049033. PMID 20926435.

- Benton, Michael J. (2010). "Saltopus, a dinosauriform from the Upper Triassic of Scotland". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 101: 285–299. doi:10.1017/S1755691011020081.

- Baron, M.G.; Norman, D.B.; Barrett, P.M. (2017). "A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution". Nature. 543: 501–506. Bibcode:2017Natur.543..501B. doi:10.1038/nature21700. PMID 28332513.

- Cabreira, Sergio Furtado; Kellner, Alexander Wilhelm Armin; Dias-da-Silva, Sérgio; Roberto da Silva, Lúcio; Bronzati, Mario; Marsola, Júlio Cesar de Almeida; Müller, Rodrigo Temp; Bittencourt, Jonathas de Souza; Batista, Brunna Jul’Armando; Raugust, Tiago; Carrilho, Rodrigo (November 2016). "A Unique Late Triassic Dinosauromorph Assemblage Reveals Dinosaur Ancestral Anatomy and Diet". Current Biology. 26 (22): 3090–3095. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.09.040. PMID 27839975.

- Garcia, Maurício S.; Müller, Rodrigo T.; Da-Rosa, Átila A.S.; Dias-da-Silva, Sérgio (April 2019). "The oldest known co-occurrence of dinosaurs and their closest relatives: A new lagerpetid from a Carnian (Upper Triassic) bed of Brazil with implications for dinosauromorph biostratigraphy, early diversification and biogeography". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 91: 302–319. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2019.02.005.

- Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Padian, Kevin; Smith, Nathan D.; Turner, Alan H.; Woody, Daniel; Downs, Alex (2007). "A Late Triassic dinosauromorph assemblage from New Mexico and the rise of dinosaurs". Science. 317 (5836): 358–361. doi:10.1126/science.1143325. PMID 17641198.

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Irmis, Randall B.; Parker, William G.; Smith, Nathan D.; Turner, Alan H.; Rowe, Timothy (2009). "Hindlimb osteology and distribution of basal dinosauromorphs from the Late Triassic of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (2): 498–516. doi:10.1671/039.029.0218.

- Ferigolo, J.; Langer, M.C. (2006). "A Late Triassic dinosauriform from south Brazil and the origin of the ornithischian predentary bone". Historical Biology. 19 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/08912960600845767. Archived from the original on 2009-06-22. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Irmis, Randall B.; Parker, William G. (2007). "A critical re-evaluation of the Late Triassic dinosaur taxa of North America". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 5 (2): 209–243. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002040.

- Nesbitt, S.J.; Sidor, C.A.; Irmis, R.B.; Angielczyk, K.D.; Smith, R.M.H.; Tsuji, L.M.A. (2010). "Ecologically distinct dinosaurian sister group shows early diversification of Ornithodira". Nature. 464 (7285): 95–98. doi:10.1038/nature08718. PMID 20203608.

- Kammerer, Christian F.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Shubin, Neil H. (2011). "The first basal dinosauriform (Silesauridae) from the Late Triassic of Morocco" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 57: 277–284. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0015.

External links

- Dinosaurs' slow rise to dominance 19 July 2007, BBC News, accessed July 2007