Tin(II) chloride

Tin(II) chloride, also known as stannous chloride, is a white crystalline solid with the formula SnCl2. It forms a stable dihydrate, but aqueous solutions tend to undergo hydrolysis, particularly if hot. SnCl2 is widely used as a reducing agent (in acid solution), and in electrolytic baths for tin-plating. Tin(II) chloride should not be confused with the other chloride of tin; tin(IV) chloride or stannic chloride (SnCl4).

_chloride.jpg) | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Tin(II) chloride Tin dichloride | |

| Other names

Stannous chloride Tin salt Tin protochloride | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.971 |

| E number | E512 (acidity regulators, ...) |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| UN number | 3260 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| SnCl2 | |

| Molar mass | 189.60 g/mol (anhydrous) 225.63 g/mol (dihydrate) |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 3.95 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 2.71 g/cm3 (dihydrate) |

| Melting point | 247 °C (477 °F; 520 K) (anhydrous) 37.7 °C (dihydrate) |

| Boiling point | 623 °C (1,153 °F; 896 K) (decomposes) |

| 83.9 g/100 ml (0 °C) Hydrolyses in hot water | |

| Solubility | soluble in ethanol, acetone, ether, Tetrahydrofuran insoluble in xylene |

| −69.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| Layer structure (chains of SnCl3 groups) | |

| Trigonal pyramidal (anhydrous) Dihydrate also three-coordinate | |

| Bent (gas phase) | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Irritant, dangerous for aquatic organisms |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page ICSC 0955 (anhydrous) ICSC 0738 (dihydrate) |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

700 mg/kg (rat, oral) 10,000 mg/kg (rabbit, oral) 250 mg/kg (mouse, oral)[1] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

Tin(II) fluoride Tin(II) bromide Tin(II) iodide |

Other cations |

Germanium dichloride Tin(IV) chloride Lead(II) chloride |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

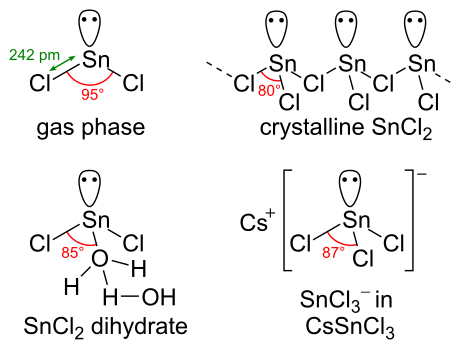

Chemical structure

SnCl2 has a lone pair of electrons, such that the molecule in the gas phase is bent. In the solid state, crystalline SnCl2 forms chains linked via chloride bridges as shown. The dihydrate is also three-coordinate, with one water coordinated on to the tin, and a second water coordinated to the first. The main part of the molecule stacks into double layers in the crystal lattice, with the "second" water sandwiched between the layers.

-chloride-xtal-1996-3D-balls-front.png)

Chemical properties

Tin(II) chloride can dissolve in less than its own mass of water without apparent decomposition, but as the solution is diluted, hydrolysis occurs to form an insoluble basic salt:

- SnCl2 (aq) + H2O (l) ⇌ Sn(OH)Cl (s) + HCl (aq)

Therefore, if clear solutions of tin(II) chloride are to be used, it must be dissolved in hydrochloric acid (typically of the same or greater molarity as the stannous chloride) to maintain the equilibrium towards the left-hand side (using Le Chatelier's principle). Solutions of SnCl2 are also unstable towards oxidation by the air:

- 6 SnCl2 (aq) + O2 (g) + 2 H2O (l) → 2 SnCl4 (aq) + 4 Sn(OH)Cl (s)

This can be prevented by storing the solution over lumps of tin metal.[3]

There are many such cases where tin(II) chloride acts as a reducing agent, reducing silver and gold salts to the metal, and iron(III) salts to iron(II), for example:

- SnCl2 (aq) + 2 FeCl3 (aq) → SnCl4 (aq) + 2 FeCl2 (aq)

It also reduces copper(II) to copper(I).

Solutions of tin(II) chloride can also serve simply as a source of Sn2+ ions, which can form other tin(II) compounds via precipitation reactions. For example, reaction with sodium sulfide produces the brown/black tin(II) sulfide:

- SnCl2 (aq) + Na2S (aq) → SnS (s) + 2 NaCl (aq)

If alkali is added to a solution of SnCl2, a white precipitate of hydrated tin(II) oxide forms initially; this then dissolves in excess base to form a stannite salt such as sodium stannite:

- SnCl2(aq) + 2 NaOH (aq) → SnO·H2O (s) + 2 NaCl (aq)

- SnO·H2O (s) + NaOH (aq) → NaSn(OH)3 (aq)

Anhydrous SnCl2 can be used to make a variety of interesting tin(II) compounds in non-aqueous solvents. For example, the lithium salt of 4-methyl-2,6-di-tert-butylphenol reacts with SnCl2 in THF to give the yellow linear two-coordinate compound Sn(OAr)2 (Ar = aryl).[4]

Tin(II) chloride also behaves as a Lewis acid, forming complexes with ligands such as chloride ion, for example:

- SnCl2 (aq) + CsCl (aq) → CsSnCl3 (aq)

Most of these complexes are pyramidal, and since complexes such as SnCl3 have a full octet, there is little tendency to add more than one ligand. The lone pair of electrons in such complexes is available for bonding, however, and therefore the complex itself can act as a Lewis base or ligand. This seen in the ferrocene-related product of the following reaction :

- SnCl2 + Fe(η5-C5H5)(CO)2HgCl → Fe(η5-C5H5)(CO)2SnCl3 + Hg

SnCl2 can be used to make a variety of such compounds containing metal-metal bonds. For example, the reaction with dicobalt octacarbonyl:

- SnCl2 + Co2(CO)8 → (CO)4Co-(SnCl2)-Co(CO)4

Preparation

Anhydrous SnCl2 is prepared by the action of dry hydrogen chloride gas on tin metal. The dihydrate is made by a similar reaction, using hydrochloric acid:

- Sn (s) + 2 HCl (aq) → SnCl2 (aq) + H

2 (g)

The water then carefully evaporated from the acidic solution to produce crystals of SnCl2·2H2O. This dihydrate can be dehydrated to anhydrous using acetic anhydride.[5]

Uses

A solution of tin(II) chloride containing a little hydrochloric acid is used for the tin-plating of steel, in order to make tin cans. An electric potential is applied, and tin metal is formed at the cathode via electrolysis.

Tin(II) chloride is used as a mordant in textile dyeing because it gives brighter colours with some dyes e.g. cochineal. This mordant has also been used alone to increase the weight of silk.

In recent years, an increasing number of tooth paste brands has been adding Tin(II) chloride as protection against enamel erosion to their formula , e. g. Oral-B or Elmex.

It is used as a catalyst in the production of the plastic polylactic acid (PLA).

It also finds a use as a catalyst between acetone and hydrogen peroxide to form the tetrameric form of acetone peroxide.

Tin(II) chloride also finds wide use as a reducing agent. This is seen in its use for silvering mirrors, where silver metal is deposited on the glass:

- Sn2+ (aq) + 2 Ag+ → Sn4+ (aq) + 2 Ag (s)

A related reduction was traditionally used as an analytical test for Hg2+(aq). For example, if SnCl2 is added dropwise into a solution of mercury(II) chloride, a white precipitate of mercury(I) chloride is first formed; as more SnCl2 is added this turns black as metallic mercury is formed. Stannous chloride can be used to test for the presence of gold compounds. SnCl2 turns bright purple in the presence of gold (see Purple of Cassius).

When mercury is analyzed using atomic absorption spectroscopy, a cold vapor method must be used, and tin (II) chloride is typically used as the reductant.

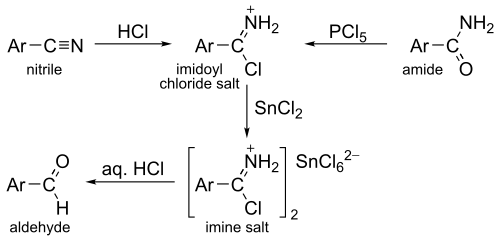

In organic chemistry, SnCl2 is mainly used in the Stephen reduction, whereby a nitrile is reduced (via an imidoyl chloride salt) to an imine which is easily hydrolysed to an aldehyde.[6]

The reaction usually works best with aromatic nitriles Aryl-CN. A related reaction (called the Sonn-Müller method) starts with an amide, which is treated with PCl5 to form the imidoyl chloride salt.

The Stephen reduction is less used today, because it has been mostly superseded by diisobutylaluminium hydride reduction.

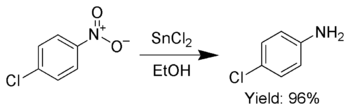

Additionally, SnCl2 is used to selectively reduce aromatic nitro groups to anilines.[7]

SnCl2 also reduces quinones to hydroquinones.

Stannous chloride is also added as a food additive with E number E512 to some canned and bottled foods, where it serves as a color-retention agent and antioxidant.

SnCl2 is used in radionuclide angiography to reduce the radioactive agent technetium-99m-pertechnetate to assist in binding to blood cells.

Aqueous stannous chloride is used by many precious metals refining hobbyists and professionals as an indicator of gold and platinum group metals in solutions.

Molten SnCl2 can be oxidised to form highly crystalline SnO2 nanostructures.[8][9]

Notes

- "Tin (inorganic compounds, as Sn)". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- J. M. Leger; J. Haines; A. Atouf (1996). "The high pressure behaviour of the cotunnite and post-cotunnite phases of PbCl2 and SnCl2". J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 57 (1): 7–16. Bibcode:1996JPCS...57....7L. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(95)00060-7.

- H. Nechamkin (1968). The Chemistry of the Elements. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- B. Cetinkaya, I. Gumrukcu, M. F. Lappert, J. L. Atwood, R. D. Rogers and M. J. Zaworotko (1980). "Bivalent germanium, tin, and lead 2,6-di-tert-butylphenoxides and the crystal and molecular structures of M(OC6H2Me-4-But2-2,6)2 (M = Ge or Sn)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 102 (6): 2088–2089. doi:10.1021/ja00526a054.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- W. L. F. Armarego; C. L. L. Chai (2009). Purification of laboratory chemicals (6 ed.). The United States of America: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Williams, J. W. (1955). "β-Naphthaldehyde". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, 3, p. 626

- F. D. Bellamy & K. Ou (1984). "Selective reduction of aromatic nitro compounds with stannous chloride in non acidic and non aqueous medium". Tetrahedron Letters. 25 (8): 839–842. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)80041-1.

- A.R.Kamali, Thermokinetic characterisation of tin(11) chloride, J Therm Anal Calorim 118(2014) 99-104.

- A.R.Kamali et al.Transformation of molten SnCl2 to SnO2 nano-single crystals, Ceram Intern 40 (2014)8533-8538.

References

- N. N. Greenwood, A. Earnshaw, Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed., Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, 1997.

- Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 71st edition, CRC Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1990.

- The Merck Index, 7th edition, Merck & Co, Rahway, New Jersey, USA, 1960.

- A. F. Wells, 'Structural Inorganic Chemistry, 5th ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1984.

- J. March, Advanced Organic Chemistry, 4th ed., p. 723, Wiley, New York, 1992.