Depictions of nudity

Depictions of nudity include visual representations of nudity throughout history, in disciplines including the arts and sciences. Nudity is restricted in most societies, but some depictions of nudity may serve a recognized social function. Clothing also serves as a significant part of interpersonal communication, and a lack of clothing in public is expected to have a social context. In Western societies, the three contexts that are easily recognized by a majority of individuals are art, pornography, and information or science. Any image not easily fitting into one of these categories may be misinterpreted, leading to disputes.[1]

Nudity in art

Nudity in art – painting, sculpture and more recently photography – has generally reflected social standards of the time in aesthetics and modesty/morality. At all times in human history, the human body has been one of the principal subjects for artists. It has been represented in paintings and statues since prehistory. Both male and female nude depictions were common in antiquity, especially in ancient Greece. Depictions of the naked body have often been used in symbolic ways, as an extended metaphor for complex and multifaceted concepts. The Roman goddess Venus, whose functions encompassed love, beauty, sex, fertility and prosperity, was central to many religious festivals in ancient Rome, and was venerated under numerous cult titles. The Romans adapted the myths and iconography of her Greek counterpart, Aphrodite, in their art and literature.

In the later classical tradition of the West, Venus was one of the most widely depicted deities of Greco-Roman mythology as the embodiment of love and sexuality. In ancient Rome, she embodied love, beauty, enticement, seduction, and persuasive female charm among the community of immortal gods; in Latin orthography, her name is indistinguishable from the noun venus ("sexual love" and "sexual desire"), from which it derives.[2][3][4]

Venus has been described both as perhaps "the most original creation of the Roman pantheon"[5] and "an ill-defined and assimilative" native goddess, combined "with a strange and exotic Aphrodite."[6] Her cults may symbolize the genuine charm and seduction of the divine by mortals, in contrast to the formal, contractual relations between most members of Rome's official pantheon and the state, and the unofficial, illicit manipulation of divine forces through magic.[7][8]

Mythological tales and stories from the Greek and Roman mythology depicting naked gods were often used as theme for the different paintings, like the scene where the two Leucippides, Leucippus daughters are abducted by Castor and Pollux. Leucippus, son of Gorgophone and Perieres, was the father of Phoebe and Hilaeira, and also of Arsinoe, mother (in some versions of the myth) of Asclepius,[9] and Eriopis (daughter by Apollo) by his wife Philodice, daughter of Inachus.[10]

Castor and Pollux abducted and married Phoebe and Hilaeira, the daughters of Leucippus. In return, Idas and Lynceus, nephews of Leucippus and rival suitors, killed Castor. Polydeuces was granted immortality by Zeus, and further persuaded Zeus to share his gift with Castor.[11]

A myth is a sacred narrative explaining how the world and humankind assumed their present form.[12][13] The myth can be defined as an "ideology in narrative form."[14] Myths may arise as either truthful depictions or overelaborated accounts of historical events, as allegory for or personification of natural phenomena, or as an explanation of ritual. They are used to convey religious or idealized experience, to establish behavioral models, and to teach.

Beside gods and goddesses the depiction of athletes and competitors and the winners of the antique competitions and Olympics were often depicted in antiquity. The bronze statue of a young athlete, found in the sea near Marathon (Attic coast), a work of the Praxiteles school, (ca. 340-330 B.C.) is only one of many examples. In Classical Greece and Rome, public nakedness was accepted in the context of public bathing or athletics. The Greek word gymnasium means "a place to be naked." Athletes commonly competed nude, but many city-states allowed no female participants at those events, Sparta being a notable exception.

The mythological themes were often used as the painter's subjects not only in the antiquity but they remained an archetypal topic during the centuries and a genre of painting with mythological subjects developed were these themes were used and reused as subjects of the artists. One example of the antique mythological themes is Danaë from Greek mythology, the mother of Perseus, who is usually depicted nude meeting her lover, depicting the scene when Zeus came to her in the form of golden rain or in the form of a shower of gold and impregnated her.

Other themes that were often used to depict the naked human body were the Biblical story of Susanna and the Elders, David, and Adam and Eve in the creation myth.

Venus de Milo at the Louvre

Venus de Milo at the Louvre Apollo and Daphne; when hunted by Apollo, the nymph turns into a tree. Sculpture by Jakob Auer (1645–1706)

Apollo and Daphne; when hunted by Apollo, the nymph turns into a tree. Sculpture by Jakob Auer (1645–1706)

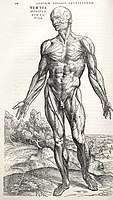

Studies of the human body

In art, a study is a drawing, sketch or painting done in preparation for a finished piece, or as visual notes.[15] Painting and drawing studies (life-drawing, sketching and anatomy) were part of the artist's education. Studies are used by artists to understand the problems involved in execution of the artists subjects and the disposition of the elements of the artist work, such as the human body depicted using light, color, form, perspective and composition.[16] Studies can be traced back as long ago as the Italian Renaissance, for example Leonardo da Vinci's and Michelangelo's studies. Anatomical studies of the human body were also executed by medical doctors. The physician Andreas Vesalius work of anatomical studies ‘‘De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body), published 1543, was a pioneering work of human anatomy illustrated by Titian's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar.

The Fabrica emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. In this work, Vesalius also becomes the first person to describe mechanical ventilation.[17] It is largely this achievement that has resulted in Vesalius being incorporated into the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists college arms and crest. Sketching is generally a prescribed part of the studies of art students, who need to develop their ability to quickly record impressions through sketching, from a live model.[18] The sketch is a rapidly executed freehand drawing that is not usually intended as a finished work.[19] The sketch may serve a number of purposes: it might record something that the artist sees, it might record or develop an idea for later use or it might be used as a quick way of graphically demonstrating an image, idea or principle.

[18] A sketch usually implies a quick and loosely drawn work, while related terms such as study, and "preparatory drawing" usually refer to more finished drawings to be used for a final work. Most visual artists use, to a greater or lesser degree, the sketch as a method of recording or working out ideas. The sketchbooks of some individual artists have become very well known,[19] including those of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Edgar Degas which have become art objects in their own right, with many pages showing finished studies as well as sketches.[20]

Study of naked man, by Michelangelo

Study of naked man, by Michelangelo Study of male anatomy, by Leonardo da Vinci

Study of male anatomy, by Leonardo da Vinci Anatomical study from Andreas Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica

Anatomical study from Andreas Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica

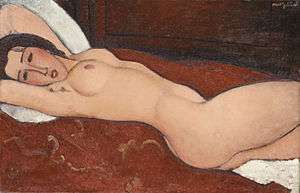

Portraits and nudes

Portraits and nudes without a pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning were a fairly common genre of art during all centuries. Some regard Goya's La Maja desnuda of around 1800, which provoked outrage in Spanish society over the model painted with and without her clothes (desnuda means nude), as "the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art",[21] but paintings of nude females were not uncommon, especially paintings of mistresses and lover of kings, dukes and other aristocrats and mistresses and wives of the artists. La Maja desnuda was different in only one way, it was exhibited on a public art exhibition.

A 1751 portrait of Marie-Louise O'Murphy, mistress to Louis XV of France, by François Boucher depicts the model lying naked on her bed, playfully stretched out with her legs apart.

The painting Gabrielle d'Estrées et une de ses soeurs (Gabrielle d'Estrées and one of her sisters), by an unknown artist circa 1594, is of Gabrielle d'Estrées, mistress of King Henry IV of France, sitting up nude in a bath, holding what is presumed to be Henry's coronation ring, while her sister, also nude, sits beside her and pinches her right nipple.[22] Henry gave Gabrielle the ring as a token of his love shortly before she died. The painting is a symbolic announcement anticipating the birth of Gabrielle's first child with Henry, César de Bourbon.[23]

Andrea Doria (1466–1560) was an Italian condottiero and admiral from Genoa. He was famous as a naval commander. For several years he scoured the Mediterranean in command of the Genoese fleet, waging war on the Turks and the Barbary pirates. Doria entered the service of King Francis I of France, who made him captain-general. On the expiration of Doria's contract he entered the service of Emperor Charles V (1528). As imperial admiral he commanded several expeditions against the Ottoman Empire.

He was generally successful and always active, although over seventy and eighty years old. Judged by the standards of his day, Doria was an outstanding leader. He chose to be depicted nude as Poseidon, the "God of the Sea." Poseidon's main domain is the ocean, and Doria was a successful admiral.[24] The god is usually depicted as an older male with curly hair and beard.

Although naked, Andrea Doria is not fragile or frail. He is depicted as a powerful virile man, showing masculine spirit, strength, vigor, and power. Bronzino's so-called "allegorical portraits", such as this Genoese admiral, Andrea Doria are less typical but possibly even more fascinating due to the peculiarity of placing a publicly recognized personality in the nude as a mythical figure.[25][26]

Helena Fourment in furs, a painting by the Flemish Baroque painter Peter Paul Rubens, shows the artist's second wife, Helena Fourment. Rubens frequently used his young wife as a model: she is also the subject of Helena Fourment, Helena Fourment in a wedding dress (1630), Helena Fourment with his son Fransem (1635) Helena Fourment with children (1636-1637), Portrait of Helena Fourment with carriage in the background (1639) and the full-figure painting of Helena in fur (1638) getting out of the bath. Helene has been featured in a pose similar to the Venus pudica (modest Venus), one of the most popular presentations of the goddess in antiquity. The young woman covers herself with a fur, but the garment leaves her breasts visible, and she looks in a teasing way at the viewer. The picture remained in Rubens' possession and had a particular importance for him. He left it to his wife in his will.

Even Manet created a scandal when he exhibited Le déjeuner sur l'herbe and Olympia, in which a model is depicted naked.

The term "Orientalism" is widely used in art to refer to the works of the many Western 19th-century artists who specialized in "Oriental" subjects, often drawing on their travels to Western Asia. Artists as well as scholars were described as "Orientalists" in the 19th century.[27] The Société des Peintres Orientalistes ("Society of Orientalist Painters") was founded in 1893, with Jean-Léon Gérôme as honorary president;[28] the word was less often used as a term for artists in 19th-century England.[29] During the 19th century, nude "odalisques" became common fantasy figures in this artistic movement, being featured in many erotic paintings from that era. La Grande Odalisque, a painting by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres from 1814, an exotic depiction in the Romantic style of an eastern concubine.

.jpg) A Portrait of Marie-Louise O'Murphy, mistress to Louis XV of France, by François Boucher, 1751

A Portrait of Marie-Louise O'Murphy, mistress to Louis XV of France, by François Boucher, 1751 The Toilette by Antoine Watteau (1684–1721)

The Toilette by Antoine Watteau (1684–1721) Francisco Goya, La Maja desnuda (The Naked Maja; painted between 1797 and 1800)

Francisco Goya, La Maja desnuda (The Naked Maja; painted between 1797 and 1800)

Depictions of youth

Amor, or Cupid, was often depicted as a baby with wings. Cupid is winged because lovers are flighty and likely to change their minds, and like a small child because love is foolish and irrational. His symbols are the arrow and torch, "because love wounds and inflames the heart." These attributes and their interpretation were established by late antiquity.[30] Although Eros appears in Classical Greek art as a slender winged youth, during the Hellenistic period he was increasingly portrayed as a chubby boy. In art, Cupid often appears in multiples as the Amores, or amorini in the later terminology of art history, the equivalent of the Greek erotes. Cupids are a frequent motif of both Roman art and later Western art of the classical tradition. In the 15th century, the iconography of Cupid starts to become indistinguishable from the putto.

Cupid continued to be a popular figure in the Middle Ages, when under Christian influence he often had a dual nature as Heavenly and Earthly love. In the Renaissance, a renewed interest in classical philosophy endowed him with complex allegorical meanings. Raphael, for example, made paintings of nude putti, sometimes incorrectly identified as cherubim. Another famous example is Amor Vincit Omnia by Caravaggio. In contemporary popular culture, Cupid is shown drawing his bow to inspire romantic love, often as an icon of Valentine's Day.[31]

In Greek mythology, Hebe is the goddess of youth, always depicted as a young girl.[32] In Roman mythology her equivalent is Juventas.[33] She is the daughter of Zeus and Hera.[34] Hebe was the cupbearer for the gods and goddesses of Mount Olympus, serving their nectar and ambrosia. She was also worshipped as a goddess of pardons or forgiveness; freed prisoners would hang their chains in the sacred grove of her sanctuary at Phlius. In art, Hebe is usually depicted wearing a sleeveless dress. The figure of Hebe was popular in the 19th century and early 20th century for garden fountains and temperance fountains, and was widely available in cast stone.

In Roman mythology, Flora is the goddess of flowers and the spring, always depicted as a young woman. While she was a comparatively insignificant figure in Roman mythology, being one among several fertility goddesses, her association with springtime gave her greater prominence with the revival of Antiquity among Renaissance humanists than she had ever enjoyed in ancient Rome. Her festival, the Floralia, was held between April 28 and May 3 and symbolized the renewal of the cycle of life, drinking, and flowers.[35] Her Greek equivalent is Chloris, a nymph. The nymphs are generally regarded as divine spirits who animate nature, and are usually depicted as beautiful, young nubile maidens who love to dance and sing. They are believed to dwell in mountains and groves, by springs and rivers, and also in trees and in valleys and cool grottoes. Although they would never die of old age or illness and could give birth to fully immortal children if mated to a god, they themselves were not necessarily immortal. As such, they could be beholden to death in various forms.

Other nymphs, always in the shape of young maidens, were part of the retinue of a god, such as Dionysus, Hermes, or Pan, or a goddess, generally the huntress Artemis.[36] They are frequently associated with the huntress Artemis; the beautiful Apollo; and the god of wine, Dionysus.

The story of Cupid and Psyche, depicted as young lovers, is an allegory of immortal love. Immortality is granted to the soul of Psyche as a reward for commitment to sexual love. In late antiquity, Martianus Capella transformed the story into an allegory of the fall of the human soul.[37] In the Gnostic text On the Origin of the World, the first rose is created from the blood of Psyche when she loses her virginity to Cupid.[38]

.jpg) Venus and Cupid by Lucas Cranach the Elder (c. 1472–1553)

Venus and Cupid by Lucas Cranach the Elder (c. 1472–1553)- Venus and Cupids by Battista Dossi (1490–1548)

Cupid and Psyche by François Gérard (1770–1837) The butterfly above her head symbolizes the soul.

Cupid and Psyche by François Gérard (1770–1837) The butterfly above her head symbolizes the soul.

Controversy

%2C_%22The_Bathers%22.jpg)

Centuries later, many painters created images of nude children that carried no religious or symbolic significance. Some sculptures depict nude child figures. A particularly famous one is Manneken Pis in Brussels, showing a nude young boy urinating into the fountain below. A female equivalent, is Jeanneke Pis.

Henry Scott Tuke painted nude young boys doing everyday seaside activities, swimming, boating, and fishing; his images were not overtly erotic, nor did they usually show their genitals.[39] Otto Lohmüller became controversial for his nude paintings of young males, which often depicted genitals. Balthus and William-Adolphe Bouguereau included nude girls in many of their paintings. Professional photographers such as Will McBride, Jock Sturges, Sally Mann, David Hamilton, Jacques Bourboulon, Garo Aida, and Bill Henson have made photographs of nude young children for publication in books and magazines and for public exhibition in art galleries. According to one school of thought, photographs such as these are acceptable and should be (or remain) legal since they represent the unclothed form of the children in an artistic manner, the children were not sexually abused, and the photographers obtained written permission from the parents or guardians. Opponents suggest that such works should be (or remain) banned and represent a form of child pornography, involving subjects who may have experienced psychological harm during or after their creation.[40]

Sturges and Hamilton were both investigated following public condemnation of their work by Christian activists including Randall Terry. Several attempts to prosecute Sturges or bookseller Barnes & Noble have been dropped or thrown out of court and Sturges's work appears in many museums, including New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.[41][42][43]

There have been incidents in which snapshots taken by parents of their infant or toddler children bathing or otherwise naked were destroyed or turned over to law enforcement as child pornography.[44] Such incidents may be examples of false allegation of child sexual abuse. Author Lynn Powell described the prosecution of such cases in terms of a moral panic surrounding child sexual abuse and child pornography.[45]

Nude photography

Since the first days of photography, the nude was a source of inspiration for those who adopted the new medium. Most of the early images were closely guarded or surreptitiously circulated as violations of the social norms of the time, since the photograph captures real nudity. Many cultures, while accepting nudity in art, shun actual nudity. For example, even an art gallery which exhibits nude paintings will typically not accept nudity in a visitor.[46]

.jpg)

Alfred Cheney Johnston (1885 – 1971) was a professional American photographer who often photographed Ziegfeld Follies.[47] He also maintained his own highly successful commercial photo studio, producing magazine ads for a wide range of upscale retail commercial products—mostly men's and women's fashions—and also photographed several hundred artists and showgirls, including nude photographs of some. Most of his nude images (some named, mostly anonymous) were, in fact, showgirls from the Ziegfeld Follies, but such daring, unretouched full-frontal images would certainly not have been openly publishable in the 1920s–1930s, so it is speculated that these were either simply his own personal artistic work, and/or done at the behest of Flo Ziegfeld for the showman's personal enjoyment. Male naked bodies were not pictured as frequently at the time. An exception is the photograph of the early bodybuilder Eugen Sandow modelling the statue The Dying Gaul, illustrating the Grecian Ideal which he introduced to bodybuilding.

.jpg) Johnston's photo of Ziegfeld Follies showgirl Dorothy Flood

Johnston's photo of Ziegfeld Follies showgirl Dorothy Flood

Erotic depictions

Sexually explicit images, other than those having a scientific or educational purpose, are generally categorized as either erotic art or pornography, but sometimes can be both. Japanese painters like Hokusai and Utamaro, in addition to their usual themes also executed erotic depictions. Such paintings were called shunga (literally: "spring" or "picture of spring"). They served as sexual guidance for newly married couples in Japan in general, and the sons and daughters of prosperous families were given elaborate pictures as presents on their wedding days. Most shunga are a type of ukiyo-e, usually executed in woodblock print format.[48] It was traditional to present a bride with ukiyo-e depicting erotic scenes from the Tale of Genji.

Shunga were relished by both men and women of all classes. Superstitions and customs surrounding shunga suggest as much; in the same way that it was considered a lucky charm against death for a samurai to carry shunga, it was considered a protection against fire in merchant warehouses and the home. The samurai, chonin, and housewives all owned shunga. All three of these groups would undergo separation from the opposite sex; the samurai lived in camps for months at a time, and conjugal separation resulted from the sankin-kōtai system and the merchants' need to travel to obtain and sell goods.[49] Records of women obtaining shunga themselves from booklenders show that they were consumers of it.[48]

The Khajuraho temples contain sexual or erotic art on the external walls of the temple. Some of the sanctuaries have erotic statuettes both on the outside of the inner wall. A small amount of the carvings contain sexual themes and those seemingly do not depict deities but rather sexual activities between human individuals. The rest depict the everyday life. These carvings are possibly tantric sexual practices.[50]

Another perspective of these carvings is presented by James McConnachie in his history of the Kamasutra.[51] McConnachie describes the zesty 10% of the Khajuraho sculptures as "the apogee of erotic art":

"Twisting, broad-hipped and high breasted nymphs display their generously contoured and bejewelled bodies on exquisitely worked exterior wall panels. These fleshy apsaras run riot across the surface of the stone, putting on make-up, washing their hair, playing games, dancing, and endlessly knotting and unknotting their girdles....Beside the heavenly nymphs are serried ranks of griffins, guardian deities and, most notoriously, extravagantly interlocked maithunas, or lovemaking couples."

Popular culture

Definitions

Nude depictions of women may be criticized by feminists as inherently voyeuristic due to the male gaze.[52] Although not specifically anti-nudity, the feminist group Guerrilla Girls point out the prevalence of nude women on the walls of museums but the scarcity of female artists. Without the relative freedom of the fine arts, nudity in popular culture often involves making fine distinctions between types of depictions. The most extreme form is full frontal nudity, referring to the fact that the actor or model is presented from the front and with the genitals exposed. Frequently, images of nude people do not go that far. They are instead deliberately composed, and films edited, such that in particular no genitalia are seen, as if the camera by chance failed to see them. This is sometimes called "implied nudity" as opposed to "explicit nudity." It is in popular culture that a particular image may lead to classification disputes.[1]

Advertising

In modern media, images of partial and full nudity are used in advertising to draw attention. In the case of attractive models this attention is due to the visual pleasure the images provide; in other cases it is due to the relative rarity of such images. The use of nudity in advertising tends to be carefully controlled to avoid the impression that a company whose product is being advertised is indecent or unrefined. There are also (self-imposed) limits on what advertising media such as magazines will allow. The success of sexually provocative advertising is claimed in the truism "sex sells." However, responses to nudity in American advertisements have been more mixed; nudity in the advertisements of Calvin Klein, Benetton, and Abercrombie & Fitch, for example, has provoked negative as well as positive responses.

An example of an advertisement featuring male full frontal nudity is one for M7 fragrance. Many magazines refused to place the ad, so there was also a version with a more modest photograph of the same model.

Magazine covers

In the early 1990s, Demi Moore posed nude for two covers of Vanity Fair: Demi's Birthday Suit and More Demi Moore. Later examples of implied nudity in mainstream magazine covers[53] have included:

- Janet Jackson (Rolling Stone, 1993)

- Jennifer Aniston (Rolling Stone, 1996 and GQ, January 2009)

- The Dixie Chicks (Entertainment Weekly, May 2003)

- Scarlett Johansson and Keira Knightley (Vanity Fair, March 2006)

- Serena Williams (ESPN The Magazine's Body issue, 2009)

- Alexander Skarsgård, Anna Paquin and Stephen Moyer; from the cast of True Blood (Rolling Stone, September 2010)

- Kim Kardashian (W, November 2010)

- Lake Bell (New York Magazine, August 2013)[54]

- Miley Cyrus (Rolling Stone, October 2013)[55]

Music album covers

Nudity is occasionally presented in other media, often with attending controversy. For example, album covers for music by performers such as Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Nirvana, Blind Faith, Scorpions and Jane's Addiction have contained nudity. Several rock musicians have performed nude on stage, including members of Jane's Addiction, Rage Against the Machine, Green Day, Black Sabbath, Stone Temple Pilots, The Jesus Lizard, Blind Melon, Red Hot Chili Peppers, blink-182, Naked Raygun, Queens of the Stone Age and The Bravery.

The provocative photo of a nude prepubescent girl on the original cover of the Virgin Killer album by the Scorpions also brought controversy.

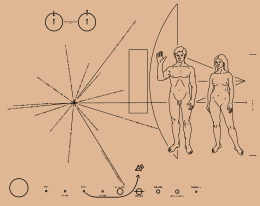

Informational

Educational

Depictions of nudity, sometimes sexually explicit, are allowed in the context of sex education as appropriate for the age of the students.

Ethnographic photography

What is generally called "ethnographic" nudity has appeared both in serious research works on ethnography and anthropology, as well as in commercial documentaries and in the National Geographic magazine in the United States. In some cases, media outlets may show nudity that occurs in a "natural" or spontaneous setting in news programs or documentaries, while blurring out or censoring the nudity in a dramatic work.[56] The ethnographic focus provided an exceptional framework for photographers to depict peoples whose nudity was, or still is, acceptable within the mores, or within certain specific settings, of their traditional culture.[57][58]

Detractors of ethnographic nudity often dismiss it as merely the colonial gaze preserved in the guise of scientific documentation. However, the works of some ethnographic painters and photographers including Herb Ritts, David LaChappelle, Bruce Weber, Irving Penn, Casimir Zagourski, Hugo Bernatzik and Leni Riefenstahl, have received worldwide acclaim for preserving a record of the mores of what are perceived as "paradises" threatened by the onslaught of average modernity.[59]

See also

- Academy figure

- Pubic hair in art

- Tableau vivant

- Striptease

- Nude (art)

- Breast imaging

Notes

- Beth A. Eck (Dec 2001). "Nudity and Framing: Classifying Art, Pornography, Information, and Ambiguity". Sociological Forum. Springer. 16 (4): 603–632. doi:10.1023/A:1012862311849. JSTOR 684826.

- Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary, 1879, "Venus", (B, Transf.), at perseus.org. It has connections to venerari (to honour, to try to please) and venia (grace, favour) through a possible common root in an Indo-European *wenes-, comparable to Sanskrit vanas- "lust, desire".

- "Venus - Origin and meaning of the name Venus by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com.

- William W. Skeat Etymological Dictionary of the English Language New York, 2011 (first ed. 1882) s. v. venerable, venereal, venial.

- Schilling, R., p. 146.

- Eden, p. 458ff. Eden is discussing possible associations between the Venus of Eryx and the brassica species Eruca sativa (known in Europe as Rocket), which the Romans considered an aphrodisiac.

- R. Schilling La religion romaine de Vénus, depuis les origines jusqu'au temps d' Auguste Paris, 1954, pp. 13–64

- R. Schilling "La relation Venus venia", Latomus, 21, 1962, pp. 3–7

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3. 10. 3

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, 511

- Ovid. Metamorphoses. Book VIII, 306.

- Dundes, Introduction, p. 1

- Kirk, "Defining", p. 57; Kirk, Myth, p. 74; Simpson, p. 3

- Lincoln, Bruce (2006). "An Early Moment in the Discourse of "Terrorism": Reflections on a Tale from Marco Polo". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 48 (2): 242–259. doi:10.1017/s0010417506000107. JSTOR 3879351.

More precisely, mythic discourse deals in master categories that have multiple referents: levels of the cosmos, terrestrial geographies, plant and animal species, logical categories, and the like. Their plots serve to organize the relations among these categories and to justify a hierarchy among them, establishing the rightness (or at least the necessity) of a world in which heaven is above earth, the lion the king of beasts, the cooked more pleasing than the raw.

- Gurney, James. "James Gurney Interview". Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Adams, Steven (1994). The Barbizon School & the Origins of Impressionism. London: Phaidon Press. pp. 31–32, 103. ISBN 0-7418-2919-3.

- Vallejo-Manzur, F.; et al. (2003). "The resuscitation greats. Andreas Vesalius, the concept of an artificial airway". Resuscitation. 56 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00346-5.

- Cf. Sue Bleiweiss, The Sketchbook Challenge, Potter Craft, 2012, pp. 10-13.

- Diana Davies (editor), Harrap's Illustrated Dictionary of Art and Artists, Harrap Books Limited, (1990) ISBN 0-245-54692-8

- Cf. Richard Brereton, Sketchbooks: The Hidden Art of Designers, Illustrators & Creatives, Laurence King, repr. ed. 2012.

- Licht, Fred (1979). Goya, the origins of the modern temper in art. New York: Universe Books. p. 83. ISBN 0-87663-294-0.

- Hagen, Rose-Marie; Rainer Hagen (2002). What Great Paintings Say, Volume 2. Köln: Taschen. p. 205. ISBN 9783822813720.

- Official site of the Louvre Museum - Portrait présumé de Gabrielle d'Estrées et de sa soeur la duchesse de Villars Archived 2009-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Burkert, Walter (1985). Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 136–39. ISBN 0-674-36281-0.

- Maurice Brock, Bronzino (Paris: Flammarion; London: Thames & Hudson, 2002).

- Deborah, Parker, Bronzino: Renaissance Painter as Poet (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

- Tromans, 20

- Harding, 74

- Tromans, 19

- Isidore, Etymologies 8.11.80.

- This introduction is based on the entry on "Cupid" in The Classical Tradition, edited by Anthony Grafton, Glenn W. Most, and Salvatore Settis (Harvard University Press, 2010), pp. 244–246.

- "Hebe's name... means 'Flower of Youth'. She was another version of her mother in the latter's quality of Hera Pais, "Hera the young maiden," observes Karl Kerenyi, The Gods of the Greeks 1951:98.

- Ovid does not detect a unity of Hera (Juno) and Hebe (Juventas): he opens Fasti vi with a dispute between Juno and Juventas claiming patronage of the month of June (on-line text).

- Hesiod, Theogony 921; Homer, Odyssey 11. 601; Pindar, Fourth Isthmian Ode; pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke 1.13, and later authors.

- Guirand, Felix; Aldington, Richard; Ames, Delano; Graves, Robert (December 16, 1987). New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology. Crescent Books. p. 201. ISBN 0517004046.

- But see Jennifer Larson, "Handmaidens of Artemis?", The Classical Journal 92.3 (February 1997), pp. 249-257.

- Danuta Shanzer, A Philosophical and Literary Commentary on Martianus Capella's De Nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii Book 1 (University of California Press, 1986), p. 69.

- Miller, Patricia Cox (2000). "'The Little Blue Flower Is Red': Relics and the Poeticizing of the Body". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 8 (2): 213–236 [p. 229]. doi:10.1353/earl.2000.0030.

- "Art Then and Now: Henry Scott Tuke". Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- GORDON, MARY (1996). "Sexualizing Children: Thoughts on Sally Mann". Salmagundi. Skidmore College (111): 144–145. JSTOR 40535995.

- Doherty, Brian (May 1998). "Photo flap". Reason. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- "Obscenity Case Is Settled". The New York Times. May 19, 1998.

- "Panel Rejects Pornography Case". The New York Times. Sep 15, 1991.

- Kincaid, James R. "Is this child pornography?". Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- Powell, Lynn (2010). Framing Innocence: A Mother's Photographs, a Prosecutor's Zeal, and a Small Town's Response. The New Press. ISBN 978-1595585516.

- Brian K. Yoder. "Nudity in Art: A Virtue or Vice?". Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- Hudovernik, Robert. Age Beauties: The Lost Collection of Ziegfeld Photographer Alfred Cheney Johnston. New York, NY: Universe Publishing/Rizzoli International Publications, 2006, HB, 272pp.

- Kielletyt kuvat: vanhaa eroottista taidetta Japanista / Förbjudna bilder: gammal erotisk konst från Japan / Forbidden Images – Erotic art from Japan's Edo Period. Helsingin kaupungin taidemuseon julkaisuja. 75. Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki City Art Museum. 2002. pp. 23–28. ISBN 951-8965-53-6.

- Kornicki, Peter F. (2001). The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 331–53. ISBN 0-8248-2337-0.

- ), swami Rajesh Chopra, liveindia.com (433, Kohat Pitampura Delhi- 110034. India. "This is a typical erotic posture from Khajuraho Gallery 9". www.liveindia.com.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Kamasutra Book PDF". planetreports.blogspot.in.

- Calogero, R. M. (2004). "A Test Of Objectification Theory: The Effect Of The Male Gaze On Appearance Concerns In College Women". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 28: 16–21.

- "Top 10 Nude Magazine Covers". Time. 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-19.

- "Lake Bell Naked for New York Magazine". August 11, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "Stars' Naked Magazine Covers". Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- "Become an Ethnographic Photographer". Archived from the original on 2012-10-31.

- "Casimir Zagourski "L'Afrique Qui Disparait" (Disappearing Africa)". Library.yale.edu. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- Mlauzi, Linje M. "Reading Modern Ethnographic Photography". Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- "Artist - Hugo Bernatzik". Michael Hoppen Gallery. Archived from the original on 2011-11-29. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

References

- Cordwell, Justine M.; Schwarz, Ronald A., eds. (1973). The Fabrics of Culture: the Anthropology of Clothing and Adornment. Chicago: International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences.

.jpg)