Koszalin

Koszalin ([kɔˈʂalʲin] (![]()

Koszalin | |

|---|---|

.jpg)

| |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Koszalin  Koszalin | |

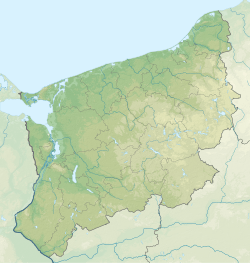

| Coordinates: 54°12′N 16°11′E | |

| Country | Poland |

| Voivodeship | West Pomeranian |

| County | city county |

| Established | 11th century |

| Town rights | 1266 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Piotr Jedliński |

| Area | |

| • Total | 98.33 km2 (37.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 32 m (105 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2019) | |

| • Total | 107,048 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 75-900, 75-902, 75-007, 75-016 |

| Area code(s) | +48 94 |

| Vehicle registration | ZK |

| Climate | Cfb |

| Website | www |

History

Middle Ages

According to the Medieval Chronicle of Greater Poland (Kronika Wielkopolska) Koszalin was one of the Pomeranian cities captured and subjugated by Duke Bolesław III Wrymouth of Poland in 1107 (other towns included Kołobrzeg, Kamień and Wolin).[4] Afterwards, in the 12th century the area became part of the Griffin-ruled Duchy of Pomerania, a vassal state of Poland, which separated from Poland after the fragmentation of Poland into smaller duchies, and became a vassal of Denmark in 1185 and a part of the multi-ethnic Holy Roman Empire from 1227 to 1806.

In 1214, Bogislaw II, Duke of Pomerania, made a donation of a village known as Koszalice/Cossalitz by Chełmska Hill in Kołobrzeg Land to the Norbertine monastery in Białoboki near Trzebiatów. New, mostly German, settlers from outside of Pomerania were invited to settle the territory. In 1248, the eastern part of Kołobrzeg Land, including the village, was transferred by Duke Barnim I to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Kammin.[5]

On 23 May 1266, Kammin bishop Hermann von Gleichen granted a charter to the village, granting it Lübeck law, local government, autonomy and multiple privileges to attract German settlers from the west.[6] When in 1276 the bishops became the sovereign in neighboring Kołobrzeg, they moved their residence there, while the administration of the diocese was done from Koszalin.[5] In 1278 a Cistercian monastery was established, which took care of the local parish church and St. Mary chapel on Chełmska Hill.[7]

The city obtained direct access to the Baltic Sea when it gained the village of Jamno (1331), parts of Lake Jamno, a spit between the lake and the sea and the castle of Unieście in 1353. Thence, it participated in the Baltic Sea trade as a member of the Hanseatic League (from 1386),[7] which led to several conflicts with the competing seaports of at Kołobrzeg and Darłowo. From 1356 until 1417/1422, the city was part of the Duchy of Pomerania-Wolgast. In 1446 Koszalin fought a victorious battle against the nearby rival city of Kołobrzeg.[7] In 1475 a conflict between the city of Koszalin and the Pomeranian duke Bogislaw X broke out, resulting in the kidnapping and temporary imprisonment of the duke in Koszalin.[7]

Modern Age

As a result of German colonization discriminatory regulations against the indigenous population were introduced.[7] In 1516 local Germans enforced a ban on buying goods from Slavic speakers.[8] It was also forbidden to accept native Slavs to craft guilds.[7]

In 1531 riots took place between supporters and opponents of the Protestant Reformation.[7] In 1534 the city became mostly Lutheran under the influence of Johannes Bugenhagen. In 1568, John Frederick, Duke of Pomerania and bishop of Cammin, started constructing a residence, finished by his successor Casimir VI of Pomerania in 1582.[7] After the 1637 death of the last Pomeranian duke, Bogislaw XIV, the city passed to his cousin, Bishop Ernst Bogislaw von Croÿ of Kammin. Occupied by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years' War in 1637, some of the city's inhabitants sought refuge in nearby Poland.[7] The city was granted to Brandenburg-Prussia after the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) and the Treaty of Stettin (1653), and with all of Farther Pomerania became part of the Brandenburgian Pomerania.

As part of the Kingdom of Prussia, "Cöslin" was heavily damaged by a fire in 1718, but was rebuilt in the following years. In 1764 on the Chełmska Hill, now located within the city limits, a Pole Jan Gelczewski founded a paper mill that supplied numerous city offices.[7] The city was occupied by French troops in 1807 after the War of the Fourth Coalition. Following the Napoleonic wars, it became the capital of Fürstenthum District (county) and Regierungsbezirk Cöslin (government region) within the Province of Pomerania. The Fürstenthum District was dissolved on 1 September 1872 and replaced with the Cöslin District on December 13. Between 1829 and 1845, a road connecting Koszalin with Szczecin and Gdańsk was built.[7] Part of this road, from Koszalin to the nearby town of Sianów, was built in 1833 by around one hundred former Polish insurgents.[7]

The town became part of the German Empire in 1871 during the unification of Germany. The railroad from Stettin (Szczecin) through "Cöslin" and Stolp (Słupsk) to Danzig (Gdańsk) was constructed from 1858–78. A military cadet school created by Frederick the Great in 1776 was moved from Kulm (Chełmno) to the city in 1890.

After the Nazi Party took power in Germany in 1933, a Gestapo station was established in the city and mass arrests of Nazi opponents were carried out.[7] After the Nazis had closed down Dietrich Bonhoeffer's seminar in Finkenwalde (a suburb of Stettin, now Szczecin) in 1937, Bonhoeffer chose the town as one of the sites where he illegally continued to educate vicars of the Confessing Church.[9] During the Second World War Köslin was the site of the first school for the "rocket troops" created on orders of Walter Dornberger, the Wehrmacht's head of the V-2 design and development program.[10] The Nazis brought many prisoners of war and forced labourers to the city, mainly Poles, but also Italians and French.[7] A labour camp of the Stalag II-B POW camp was located in the city.[11] After crushing the Warsaw Uprising, the Germans brought several transports of Poles from Warsaw to the city, mainly women and children.[12]

After World War II

On 4 March 1945, the city was captured by the Red Army. Under the border changes forced by the Soviet Union in the post-war Potsdam Agreement, Koszalin became part of Poland as part of the so-called Recovered Territories. The city's German population that had not yet fled was expelled to the remainder of post-war Germany in accordance to the Potsdam Agreement. The city was resettled by Poles and Kashubians, many of whom had been expelled from Polish territory annexed by the Soviets.[13]

As early as March 1945 a Polish police unit was established, consisting of former forced labourers and prisoners of war, however, the Soviets, still present in the city, plundered local industrial factories in April.[14] From May 1945, life in the destroyed city was being organized, the first post-war schools, shops and service premises were established.[14] In 1946, the first public library was opened, whose director was later Maria Pilecka, the sister of Polish national hero Witold Pilecki.[15] In March 1946, the anti-communist Home Army 5th Wilno Brigade was active in Koszalin.[14] In July 1947, the last units of the Soviet Army left Koszalin, and from that time only Polish troops were stationed in the city.[14] In 1953 a local radio station was founded in Koszalin.[7]

Initially, Koszalin was the first post-war regional capital of Polish Western Pomerania, before the administration finally moved to Szczecin in February 1946, after which the region was named the Szczecin Voivodeship.[7] In 1950 this voivodeship was divided into a truncated Szczecin Voivodeship and Koszalin Voivodeship. In years 1950-75 Koszalin was the capital of the enlarged Koszalin Voivodeship sometimes called Middle Pomerania due to becoming the fastest growing city in Poland. In years 1975-98 it was the capital of the smaller Koszalin Voivodeship. As a result of the Local Government Reorganization Act (1998) Koszalin became part of the West Pomeranian Voivodeship (effective 1 January 1999) regardless of an earlier proposal for a new Middle Pomeranian Voivodeship covering approximately the area of former Koszalin Voivodeship (1950–75).

In 1991, Koszalin was visited by Pope John Paul II.[16] On the fifth anniversary of his visit, his monument was unveiled in the city center.[16]

Landmarks

The city borders on Chełmska Hill (Polish: Góra Chełmska), a site of pagan worship in prehistory, and upon which is now built the tower "sanctuary of the covenant", which was consecrated by Pope John Paul II in 1991, and is currently a pilgrimage site. Also an observation tower is located on the hill. At the entrance to the sanctuary there is a monument dedicated to the Polish November insurgents of 1831, who, imprisoned by Prussian authorities, built a road connecting Koszalin with nearby Sianów.[17]

Koszalin's most distinctive landmark is the Gothic St. Mary's Cathedral, dating from the early 14th century. Positioned in front of the cathedral is a monument commemorating John Paul II's visit to the city.

Other city landmarks include the Park of the Dukes of Pomerania (Park Książąt Pomorskich), the Koszalin Museum, the main post office, the 16th-century Wedding Palace and the Culture Centre 105 (Centrum Kultury 105).

The city also has monuments dedicated to Polish national heroes: Józef Piłsudski, Władysław Anders, Kazimierz Pułaski, Władysław Sikorski, as well monuments of the 19th-century Polish poets Cyprian Norwid and Adam Mickiewicz.[18]

Observation tower on Góra Chełmska

Observation tower on Góra Chełmska Koszalin Museum

Koszalin Museum The new building of the Koszalin Philharmonic

The new building of the Koszalin Philharmonic A historic villa on Zwycięstwa Street

A historic villa on Zwycięstwa Street- Park of the Dukes of Pomerania (Park Książąt Pomorskich)

Memorial stone dedicated to Kazimierz Pułaski in the Amphitheater Park

Memorial stone dedicated to Kazimierz Pułaski in the Amphitheater Park

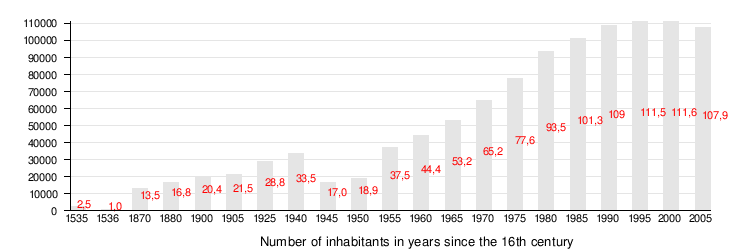

Demographics

Before World War II the population of the town was composed of Protestants, Jews and Catholics.

|

|

|

Climate

The climate is oceanic (Köppen: Cfb) with some humid continental characteristics (Dfb), usually categorized if the 0 °C isotherm is used (for the same classification). Being in Western Pomerania and near the Baltic Sea, it has a much more moderate climate than the other large Polish cities. The summers are warm and practically never hot as in the south and the winters are often more moderate than the northeast and east, although still cold, yet it is not as mild as Western Europe. Daily averages below freezing point can be found in January and February, while in the summer they are between 15 and 16 °C, relatively cool. The average annual precipitation is 704 mm, distributed during the year. Koszalin is one of the sunniest cities in the country.[19][20][21]

| Climate data for Koszalin (Wilkowo), elevation: 33 m, 1961-1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

34.9 (94.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

33.9 (93.0) |

33.9 (93.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

34.9 (94.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.8 (69.4) |

21.0 (69.8) |

17.3 (63.1) |

12.5 (54.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.6 (36.7) |

11.4 (52.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.4 (29.5) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.1 (43.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.1 (39.4) |

0.4 (32.7) |

7.6 (45.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.9 (25.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.3 (54.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.7 (−16.1) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.6 (36.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−13.7 (7.3) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 43 (1.7) |

30 (1.2) |

35 (1.4) |

39 (1.5) |

55 (2.2) |

72 (2.8) |

88 (3.5) |

74 (2.9) |

82 (3.2) |

62 (2.4) |

69 (2.7) |

55 (2.2) |

704 (27.7) |

| Average rainy days | 10.9 | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 11.3 | 9.4 | 11.1 | 9.5 | 12.6 | 11.6 | 118.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 37.2 | 61.6 | 108.5 | 159.0 | 235.6 | 231.2 | 213.9 | 210.8 | 135.1 | 93.0 | 39.3 | 27.9 | 1,553.1 |

| Source: HKO[22] and NOAA[19] | |||||||||||||

Sports

- AZS Koszalin - men's basketball team, playing in the Polish Basketball League (the top division)

- AZS Politechnika Koszalin - women's handball team playing in Polish Ekstraklasa Women's Handball League: 3rd place in 1st league in 2003/2004 season; promoted to Premiership in 2004/2005 season.

- Gwardia Koszalin - football team, currently playing in the fourth Polish division.

- Bałtyk Koszalin - football team, currently playing in the fourth Polish division

- Tennis - Bałtyk Koszalin

- Rugby - Rugby Club Koszalin

- Motorsport - Klub Motor Sport Koszalin

- American Football - Korsarze Koszalin

Major corporations

- Zakład Energetyczny Koszalin SA

- Brok Brewery SA

- Nordglass Autoglass

- TWIP Foundation

Education

- Koszalin University of Technology (Politechnika Koszalińska)

- Baltic College (Bałtycka Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczna)

- Air Force training center (Centrum Szkolenia Sił Powietrznych im. Romualda Traugutta)

- Koszalin University of Humanities (Koszalińska Wyższa Szkoła Nauk Humanistycznych)

- State Higher Vocational School in Koszalin (Państwowa Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa w Koszalinie)

- Major Seminary of the Diocese of Koszalin-Kolobrzeska in Koszalin (Wyższe Seminarium Duchowne Diecezji Koszalińsko-Kołobrzeskiej w Koszalinie)

- Team State School of Music (Zespół Państwowych Szkół Muzycznych im. Grażyny Bacewicz)

- School Arts Team (Zespół Szkół Plastycznych im. Władysława Hasiora)

- 1st. High School Stanisława Dubois (Dubois or colloquially Dibulec)

- 2nd. High School Władysława Broniewskiego (colloquially Bronek)

- 5th. High School Stanisława Lema (Jedności)

- 6th. High School Cypriana Norwida (Podgórna)

Notable people

- Daniel Liczko (1615- 1662), Sergeant of the Dutch colonial army in New Amsterdam

- Ewald Christian von Kleist (1715–1759) a German poet and cavalry officer [23]

- Rudolf Clausius (1822–1888) German physicist and mathematician and a founder of thermodynamics [24]

- Karl Adolf Lorenz (1837–1923), conductor, composer and music pedagogue

- Hans Richert (1869–1940), school reformer

- Hans Grade (1879–1946), aviation pioneer

- Fritz von Brodowski (1886–1944) a German army general, controversially killed while in French custody during WWII

- Georg Wendt (1889–1948) a German politician, member of the SPD and SED

- Friedrich-Karl Burckhardt (1889-1962), World War I flying ace

- Peter von Heydebreck (1889–1934), NSDAP politician

- Paul Dahlke (1904–1984) a German stage and film actor

- Heinz Pollay (1908–1979) a German dressage horse rider, competed in the 1936 and 1952 Summer Olympics

- Martin Ruhnke (1921–2004), musicologist

- Hans-Joachim Preil (1923–1999), actor and comedian

- Leslie Brent (1925–2019), immunologist and zoologist

- Waltraud Nowarra (1940–2007) a German chess player

- Vladimir Berdnikov (born 1946), painter and glass artist

- Mirosław Okoński (born 1958), footballer, played 418 pro games and 29 for Poland

- Kuba Wojewódzki (born 1963) a Polish journalist, TV personality, drummer and comedian

- Mirosław Trzeciak (born 1968), footballer, director of sport development of Legia Warszawa

- Marcin Horbacz (born 1974) a Polish modern pentathlete, competed at the 2008 Summer Olympics

- Maciej Stachowiak (born 1976), software engineer at Apple Inc.

- Kasia Cerekwicka (born 1980) a Polish pop singer

- Paweł Spisak (born 1981) a Polish equestrian, competed at the 2004, 2008, 2012 and 2016 Summer Olympics

- Sebastian Mila (born 1982), footballer

- Joanna Alpop (born 1983), musician

- Joanna Majdan (born 1988), chess player

International relations

Koszalin is twinned with:[25]

References

- "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 30 June 2020. Data for territorial unit 3261000.

- "Former Territory of Germany" (in German). 2017-11-14.

- "Interview with Mr. Piotr Jedliński, Mayor of Koszalin, Poland". CEOWORLD Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- "Historia Koszalina, Serwis Urzędu Miejskiego w Koszalinie". Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- Gerhard Köbler, Historisches Lexikon der Deutschen Länder: die deutschen Territorien vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart, 7th edition, C.H. Beck, 2007, p. 113, ISBN 3-406-54986-1

- Charles Higounet. Die deutsche Ostsiedlung im Mittelalter (in German). p. 149.

- "Kalendarium 750 lat Koszalina, Muzeum w Koszalinie" (in Polish). Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- Hieronim Kroczyński, Kołobrzeg zarys dziejów, Wyd. Poznańskie, Poznań, 1979, p. 27 (in Polish)

- Peter Zimmerling, Bonhoeffer als praktischer Theologe, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2006, p.59, ISBN 3-525-55451-6

- p.37, Dornberger

- "Les Kommandos". Stalag IIB Hammerstein, Czarne en Pologne (in French). Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- Leszek Laskowski, Pomniki Koszalina, Koszalin 2009, p. 104 (in Polish)

- W. Seidel: Das Land und Volk der Kassuben. In: Preußische Provinzialblätter N.F. 2 (1852), p. 104.

- "Kalendarium Koszalina z lat 1945-1950, Muzeum w Koszalinie" (in Polish). Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- Laskowski, Op. cit., p. 114

- Laskowski, Op. cit., p. 7

- Laskowski, Op. cit., p. 46-47

- Laskowski, Op. cit., p. 8, 14-17, 44-45, 63

- "Koszalin (12105) - WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved December 26, 2018. Archived December 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine.

- Engel, Pamela. "MAP: Here's Where You Should Move If You Want The Most Sunshine". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- "Koszalin climate: Average Temperature, weather by month, Koszalin weather averages - Climate-Data.org". en.climate-data.org. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- "Hong Kong Observatory". HKO. December 2012. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 06 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Miasta partnerskie". Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Twin Cities". Kristianstads kommun. 2015-04-15. Archived from the original on 2016-04-06. Retrieved 2016-06-06.

External links

- Official City Authorities site

- Technical University of Koszalin

- ChefMoz Dining Guide

- Unofficial Forum of Koszalin's Community

- Koszalin in Your Wonder Beautiful Place

- http://www.koszalincity.pl/ (Polish)

- Heimatkreis Köslin (German refugee's organization) (in German)