Compsognathidae

Compsognathidae is a family of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaurs. They were small carnivores, generally conservative in form, hailing from the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods. The bird-like features of these species, along with other dinosaurs such as Archaeopteryx inspired the idea for the connection between dinosaur reptiles and modern-day avian species.[4] Compsognathid fossils preserve diverse integument — skin impressions are known from four genera commonly placed in the group, Compsognathus, Sinosauropteryx, Sinocalliopteryx, and Juravenator.[5] While the latter three show evidence of a covering of some of the earliest primitive feathers over much of the body, Juravenator and Compsognathus also show evidence of scales on the tail or hind legs.

| Compsognathidae | |

|---|---|

| |

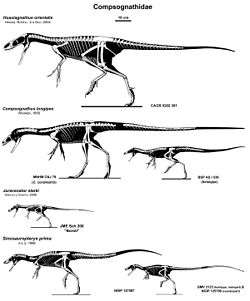

| Compsognathid skeletons to scale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Neocoelurosauria |

| Family: | †Compsognathidae Cope, 1871 |

| Type species | |

| †Compsognathus longipes Wagner, 1861 | |

| Genera[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

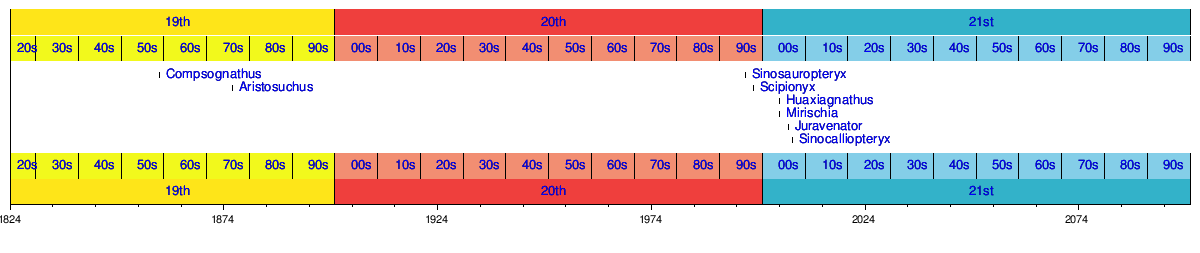

The first member of the group, Compsognathus, was discovered in 1861, after Johann A. Wagner published his description of the taxon.[6][7][8] The family was created by Edward Drinker Cope in 1875.[9] This classification was accepted by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1882, and added to the Coelurosauria clade by Friedrich von Huene in 1914 after additional fossils had been found.[6] With further discoveries, fossils have been uncovered across three different continents, in Asia,[10][6] [6][7][8][5] Europe,[11] and South America.[7][9] Assignment to Compsognathidae is usually determined through examination of the metacarpal, which is used to separate Compsognathidae from other dinosaurs.[12] However, classification is still complicated due to similarities to the body of several other theropod dinosaurs, as well as the lack of unifying, diagnostic features that are shared by all compsognathids.[9][13]

History of Discovery

The first significant fossil specimen of Compsognathidae was found in the Bavaria region of Germany (BSP AS I 563) and given to collector Joseph Oberndorfer in 1859.[14] The finding was initially significant because of the small size of the specimen. In 1861, after an initial period of review, Johann A. Wagner presented his analysis of the specimen to the public and named the fossil Compsognathus longipes ("elegant jaw").[15] In 1868, Thomas Henry Huxley, an explorer known for his travels with Charles Darwin and an early supporter of the theory of evolution, used Compsognathus in a comparison to similar feathered dinosaur Archaeopteryx in order to propose the origin of birds. While Huxley noticed that these dinosaurs shared a similar layout to birds and proposed an exploration of the similarities. He is credited as being the first person to do so.[16] This initial comparison sparked the interest into the origin of birds and feathers. In 1882, Othniel Charles Marsh named a new family of dinosaurs for this species Compsognathidae and officially recognized the species as part of Dinosauria.[17]

Notable Specimens

In 1971, a second nearly complete specimen of Composgnathus longipes was found in the area of Canjuers, which is located in the southeast of France near Nice.[6] This specimen was much larger than the original German specimen, but similarities led to experts categorizing the fossil as an adult Compsognathus longipes and leading to the further classification of the German specimen as a juvenile.[18] This specimen also contained a lizard in the digestive region, further solidifying the theory that compsognothids consumed small vertebrate species.

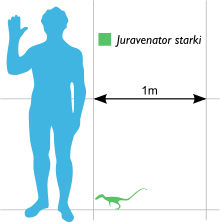

The holotype of Juravenator is the only known specimen of the species. Though Juravenator has previously been accepted as a member of Compsognathidae, recent research has led some experts to believe that Juravenator does not belong in this group. This is due to the fact that Juravenator could also be classified into a similar group within Coelurosauria, Maniraptoriformes. Maniraptorformes share many similarities with compsognathids and due to the fact that there has been only one verified specimen of Juravenator, experts have disagreed on exactly where to place this genus. Since 2013, Juravenator is still commonly classified as a coelurosaur, but near the family Maniraptorformes instead of Compsognathidae.[19]

A compsognathid specimen consisting of a single finger bone has been described from Late Jurassic (Tithonian Age, about 150 million years ago) sediments at Port Waikato, New Zealand. It is the first and so far, only dinosaur specimen known from Jurassic New Zealand, as well as being the first New Zealand dinosaur fossil to have been found outside of the Cretaceous marine sediments at Mangahouanga Stream. Possible coprolites have been referred to this specimen, however it is still not an officially classified species.

Timeline

Description

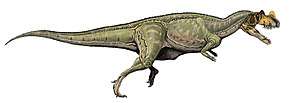

Compsognathids share a variety of characteristics. The genera in this family demonstrate traits that are characteristic of theropods, such as smaller forelimbs than hind legs. Size, feathers, and metacarpal size are among the most important classifying common characteristics.

Size

Compsognathids are considered to be among the smallest dinosaurs ever discovered. Compsognathus longipes was formerly the smallest known dinosaur. It was around the size of a chicken when fully grown: around 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long and weighing 2.5 kg (5.5 lb).[20] However, recently discovered adult specimens of other dinosaurs are smaller than Compsognathus, including Caenagnathasia, Microraptor, and Parvicursor, all of which are estimated to be less than 1 m long.[21] However, most of these specimens are incomplete, so these sizes remain estimates.

The other genera in this family are slightly larger than Compsognathus longipes, but generally similar in size. The largest compsognathid is Huaxiagnathus, which is estimated from its holotype to be around 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) long,[22] while Sinocalliopteryx measures around 2.4 m (7 ft 10 in) long.[23] Sinosauropteryx is the most similar to Compsognathus, measuring at most 1.07 m (3 ft 6 in) long.[24]

Feathers

Compsognathids had feathers. The phylogeny of Compsognathidae organizes this family near the development of feathers in dinosaurs. In 1998, evidence of filamentous protofeathers was presented in a study on Sinosauropteryx, marking the first time that any sort of feather structure was found outside of birds and their related species.[25] After this, more evidence of feather structure was found in other genera of Compsognathidae. Evidence of protofeathers bearing resemblance to Sinosauropteryx was found on Sinocalliopteryx specimens, including on the foot of the specimen.[26] There have been signs of basic feather structures on Juravenator, but evidence of this is still not definite. Samples of Juravenator skin show scales instead of feathers, leading into debates about Juravenator’s place within the family Compsognathidae.[27] However, a 2010 examination of Juravenator under UV light showed filaments similar to those seen on other compsognathid specimens, indicating that it is likely that these dinosaurs had some sort of feathering.[28]

Metacarpals

Another way of classification of Compsognathidae is shared metacarpal morphology. A 2007 study found similarities between compsognathid genera in certain metacarpal I morphologies. The conclusion of this study found that Composgnathidae had a distinct manual morphology where, like theropods, the first digit of the manus is larger than the other digits, but with a distinct metacarpal I morphology where the metacarpal is stocky and short. Compsognathidae also has a projection from the manus that is on this metacarpal.[12]

Palaeobiology

Diet

Compsognathidae were carnivores and certain specimens have contained the remains of their diet. The German specimen of Compsognathus included remains in the digestive region, which was initially thought to be an unborn embryo.[29] However, further analysis found that the remains belong to a lizard with an elongated tail and stretched legs.[17][30] Other compsognathids, such as Sinosauropteryx, have been shown to eat lizards.[24]

References

- Hendrickx, C., Hartman, S.A., & Mateus, O. (2015). An Overview of Non- Avian Theropod Discoveries and Classification. PalArch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology, 12(1): 1-73.

- J. N. Choiniere, J. M. Clark, C. A. Forster and X. Xu. 2010. A basal coelurosaur (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Jurassic (Oxfordian) of the Shishugou Formation in Wucaiwan, People's Republic of China. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30(6):1773-1796

- Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- Etnier, Michael A. "Neptune's Ark: From Ichthyosaurs to Orcas." (2008): 25.

- Xu, Xing. "Palaeontology: Scales, feathers and dinosaurs." Nature 440.7082 (2006): 287-288.

- Peyer, Karin. "A reconsideration of Compsognathus from the Upper Tithonian of Canjuers, southeastern France." Journal of vertebrate Paleontology 26.4 (2006): 879-896.

- Sales, Marcos AF, Paulo Cascon, and Cesar L. Schultz. "Note on the paleobiogeography of Compsognathidae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and its paleoecological implications." Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 86.1 (2014): 127-134.

- Wagner, A. "Neue Beiträge zur Kenntnis der urweltlichen Fauna des lithographischen Schiefers; V. Compsognathus longipes Wagner." Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 9 (1861): 30-38.

- Naish, Darren, David M. Martill, and Eberhard Frey. "Ecology, systematics and biogeographical relationships of dinosaurs, including a new theropod, from the Santana Formation (? Albian, Early Cretaceous) of Brazil." Historical Biology 16.2-4 (2004): 57-70.

- Shu'an, Ji, et al. "New material of Sinosauropteryx (Theropoda: Compsognathidae) from western Liaoning, China." Acta Geologica Sinica (English Edition) 81.2 (2007): 177-182.

- Dal Sasso C., Maganuco S. "Scipionyx samniticus (Theropoda: Compsognathidae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Italy: osteology, ontogenetic assessment, phylogeny, soft tissue anatomy, taphonomy and palaeobiology." Memorie, XXXVI-I (2011): 1-283.

- Gishlick, Alan D., and Jacques A. Gauthier. "On the manual morphology of Compsognathus longipes and its bearing on the diagnosis of Compsognathidae." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149.4 (2007): 569-581.

- Brett-Surman, Michael K., Thomas R. Holtz, and James O. Farlow, eds. The complete dinosaur. Indiana University Press, 2012 pp 360.

- Wellnhofer, P. (2008). "Dinosaurier". Archaeopteryx — der Urvogel von Solnhofen. Munich: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. p. 256. ISBN 978-3-89937-076-8.

- Wagner, Johann Andreas (1861). "Neue Beiträge zur Kenntnis der urweltlichen Fauna des lithographischen Schiefers; V. Compsognathus longipes Wagner". Abhandlungen der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 9: 30–38.

- Switek, B. (2010). Thomas Henry Huxley and the reptile to bird transition. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 343(1), 251-263.

- Ostrom, J. H. (1978). The osteology of Compsognathus longipes Wagner. Zitteliana.

- Callison, G.; H. M. Quimby (1984). "Tiny dinosaurs: Are they fully grown?". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 3 (4): 200–209. doi:10.1080/02724634.1984.10011975.

- Godefroit, Pascal; Cau, Andrea; Hu, Dong-Yu; Escuillié, François; Wu, Wenhao; Dyke, Gareth (2013). "A Jurassic avialan dinosaur from China resolves the early phylogenetic history of birds". Nature. 498 (7454): 359–362. Bibcode: 2013Natur.498..359G. doi:10.1038/nature12168. PMID 23719374

- "What was the biggest dinosaur? What was the smallest?" (May 17, 2001)

- Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 152

- Hwang SH, Norell MA, Ji Q, Gao K-Q (2004) A large compsognathid from the Early Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China. J Syst Pal 2: 13–30. doi:10.1017/S1477201903001081.

- Therrien, F., & Henderson, D. M. (2007). My theropod is bigger than yours… or not: estimating body size from skull length in theropods. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 27(1), 108-115.

- Switek, Brian (August 31, 2012). "Stomach Contents Preserve Sinocalliopteryx Snacks"

- Chen, P.; Dong, Z.; Zhen, S. (1998). "An exceptionally well-preserved theropod dinosaur from the Yixian Formation of China". Nature. 391 (8): 147–152. doi:10.1038/34356.

- Ji, S., Ji, Q., Lu J., and Yuan, C. (2007). "A new giant compsognathid dinosaur with long filamentous integuments from Lower Cretaceous of Northeastern China." Acta Geologica Sinica, 81(1): 8-15

- Goehlich, U.B.; Tischlinger, H.; Chiappe, L.M. (2006). "Juravenator starki (Reptilia, Theropoda) ein neuer Raubdinosaurier aus dem Oberjura der Suedlichen Frankenalb (Sueddeutschland): Skelettanatomie und Weichteilbefunde". Archaeopteryx. 24: 1–26.

- Chiappe, L.M.; Göhlich, U.B. (2010). "Anatomy of Juravenator starki (Theropoda: Coelurosauria) from the Late Jurassic of Germany". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 258 (3): 257–296. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0125.

- Report of the 65th Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, Ipswich, 1895, London, 1895, 743

- Nopcsa, Baron F. (1903). "Neues ueber Compsognathus". Neues Jahrbuch fur Mineralogie, Geologie und Palaeontologie (Stuttgart). 16: 476–494.