Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque (Turkish: Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii; also named Hazreti Cabir Camii) is a former Eastern Orthodox church in Istanbul, converted into a mosque by the Ottomans. The dedication of the church is obscure. For a long time it has been identified with the church of Saints Peter and Mark, but without any proof. Now it seems more probable that the church is to be identified with Saint Thekla of the Palace of Blachernae (Greek: Άγία Θέκλα τοῦ Παλατίου τῶν Βλαχερνών, Hagia Thekla tou Palatiou tōn Vlakhernōn).[1] The building belongs stylistically to the eleventh-twelfth century.

| Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Atik Mustafa Paşa Camii | |

|---|---|

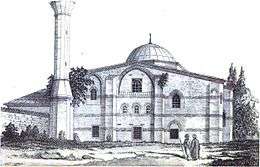

The mosque viewed from southeast in a drawing of 1877, from A.G. Paspates' Byzantine topographical studies | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Year consecrated | Between 1509 and 1512 |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

Location in the Fatih district of Istanbul | |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°02′18.96″N 28°56′38.40″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church with Greek cross plan |

| Style | Byzantine |

| Completed | 1059 |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Materials | brick, stone |

Location

The building lies in the district of Fatih, in the neighborhood of Ayvansaray, in Çember Sokak. It lies a few hundred metres inside the walled city, at a short distance from the shore of the Golden Horn, at the foot of the sixth hill of Constantinople.

History

Towards the middle of the ninth century, Princess Thekla, eldest daughter of Emperor Theophilus enlarged a small oratory, dedicated to her patron saint and namesake, lying 150 metres (490 feet) east of the Church of Theotokos of the Blachernae.[2] In 1059 on this site, Emperor Isaac I Komnenos built a larger church, as thanks for surviving a hunting accident.[3] The church was famous for its beauty, and Anna Comnena writes that her mother, Anna Dalassena, used to go often and pray there.[3] After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, the building was heavily damaged during the earthquake of 1509, which destroyed the dome.[4] Shortly after that, Kapicibaşi[5] (and later Grand Vizier) Koca Mustafa Pasha, executed in 1512,[6] repaired the damages and converted the church into a mosque.[7] Up to the end of nineteenth century, a Hamam, placed 150 metres (490 feet) south of the building, also belonged to the mosque's foundation.[2] In 1692, Şatir Hasan Ağa built a fountain in front of the mosque.[2] In 1729, during the great Fire of Balat, the building was heavily damaged and repaired some years later. It was damaged again during the 1894 Istanbul earthquake, which destroyed the minaret, and reopened for worship in 1906. A last restoration occurred in 1922.[2] In that occasion, a marble christening font was brought to the Istanbul Archaeology Museum.[2] Inside the south apse of the building there is the türbe (tomb) attributed to Hazreti Cabir (Jabir) Ibn Abdallah-ül-Ensamı, one of the companions of Eyüp,[8] fallen nearby in 678 during the first Arab siege of Constantinople.[9]

Architecture

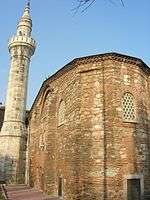

The building is 15 metres (49 feet) wide and 17.5 metres (57 feet) long, and has a domed Greek cross plan. It is oriented in a northeast – southwest direction. It has 3 polygonal apses, and the narthex has been destroyed.[10] The edifice has no galleries, and the dome, which has no drum, is almost certainly Ottoman, although the arches and the piers which sustain it are Byzantine.[11] The arms of the cross, the pastophoria, the Prothesis and Diaconicon are covered with barrel vaults, and communicate through arches. The north and south walls have a floor level with three arcades, a first level with three windows, and a second level with a window with three lights.[11] On the southeast side, the three apses project boldly outside with three sides.[11] The roof, the cornice and the wooden narthex, which replaced the old Byzantine narthex, are Ottoman. A cruciform font which belonged to the baptistery of the church and lay on the other side of the street[11] has been moved to the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. The dome piers, which form the internal side of the cross, are L-shaped. They are an example of the stage preceding that of the cross-in-square church with four columns.[11] Remains of frescoes placed on the south side of the building have been published.[12] Moreover, during the floor renewal in the 1990s, several tesserae have been found, showing the previous existence of mosaics panels and frescoes in the building.[13] Despite its architectural significance, the building has never undergone a systematic study.[14]

Gallery

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Exterior

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Exterior Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Facade detail

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Facade detail Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Decoration

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Decoration Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Interior

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Interior Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque 6189

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque 6189 Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque 4764

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque 4764 Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Türbe

Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque Türbe

References

- The Church of Saint Thekla was also previously identified with the Toklu Dede Mescidi, a Church of Comnenian foundation (middle/second half of eleventh century) which lied nearby and was destroyed in 1929. This identification, based only on the similarity of the name, should be rejected. Janin (1953), p. 148.

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 83.

- Janin (1953), p. 148.

- Information contained in an inscription on the front of the Mosque.

- The Kapicibaşi ("chief doorkeeper") was also master of ceremonies at receptions for foreign ambassadors.

- Eyice (1955), p. 92.

- In the same period he converted also another byzantine church, this one placed in today's Samatya neighborhood, into a mosque, named after him Koca Mustafa Pasha Mosque.

- Eyice (1955), p. 66.

- Gülersoy (1976), p. 248.

- Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 82.

- Van Millingen (1912), p. 193.

- In 1985, a Dumbarton Oaks Paper (Vol. 39, pp. 125-134) about them has been published.

- Tunay (2001), p. 229

- Unfortunately, in the occasion of the floor renewal, the Vakıflar Genel Müdürlüǧü ("general directorate for the pious foundations") denied the permission for an archeological survey, which could have clarified many open issues, including that about its dedication. Tunay (2001), p. 229

Sources

- Van Millingen, Alexander (1912). Byzantine Churches of Constantinople. London: MacMillan & Co.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). La Géographie ecclésiastique de l'Empire byzantin. 1. Part: Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique. 3rd Vol. : Les Églises et les Monastères (in French). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines.

- Mamboury, Ernest (1953). The Tourists' Istanbul. Istanbul: Çituri Biraderler Basımevi.

- Eyice, Semavi (1955). Istanbul. Petite Guide a travers les Monuments Byzantins et Turcs (in French). Istanbul: Istanbul Matbaası.

- Gülersoy, Çelik (1976). A Guide to Istanbul. Istanbul: Istanbul Kitaplığı. OCLC 3849706.

- Müller-Wiener, Wolfgang (1977). Bildlexikon Zur Topographie Istanbuls: Byzantion, Konstantinupolis, Istanbul Bis Zum Beginn D. 17 Jh (in German). Tübingen: Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-1022-3.

- Tunay, Mehmet (2001). "Byzantine Archeological Findings in Istanbul". In Necipoğlu, Nevra (ed.). Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and everyday Life. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11625-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Atik Mustafa Pasha Mosque. |