Ceratosauria

Ceratosaurs are members of a group of theropod dinosaurs defined as all theropods sharing a more recent common ancestry with Ceratosaurus than with birds. Ceratosaurs are believed to have diverged from the rest of Theropoda by the early Jurassic, however, the oldest confirmed discovered specimens date to the Late Jurassic. According to the majority of the latest research, Ceratosauria includes the Late Jurassic to Late Cretaceous theropods Ceratosaurus, Elaphrosaurus, and Abelisaurus, found primarily (though not exclusively) in the Southern Hemisphere. Originally, Ceratosauria included the above dinosaurs plus the Late Triassic to Early Jurassic Coelophysoidea and Dilophosauridae, implying a much earlier divergence of ceratosaurs from other theropods. However, most recent studies have shown that coelophysoids and dilophosaurids do not form a natural group with other ceratosaurs, and are excluded from this group.[1]

| Ceratosaurs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal reconstruction of Ceratosaurus nasicornis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Neotheropoda |

| Clade: | Averostra |

| Clade: | †Ceratosauria Marsh, 1884 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

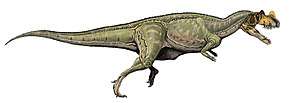

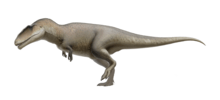

Ceratosauria derives its names from the type species, Ceratosaurus nasicornis, described by O.C. Marsh in 1884. A moderately large predator from the Late Jurassic, Ceratosaurus nasicornis, was the first ceratosaur to be discovered. Ceratosaurs are generally moderately large in size, with some exceptions like the larger Carnotaurus and the significantly smaller noasaurs. The major defining characteristics of Ceratosauria include a robust skull with increased ornamentation or height and a shortening of the arms.[2] Both of these characteristics are generally accentuated in later members of the group, such as the abelisaurs, whereas more basal species such as C. nasicornis appear more similar to other basal theropods. The highly fragmented nature of the ceratosaur fossil record means that the characteristics, relationships, and early history of Ceratosauria remain mysterious and highly debated.

Phylogeny

Historical Phylogeny

Ceratosauria was first described by O.C. Marsh in the American Journal of Science in 1884. Writing about the newly discovered C. nasicornis, he noted the similarities between the firmly united metatarsals of C. nasicornis and those of Archaeopteryx. Since C. nasicornis was the only other dinosaur discovered at the time to share this trait, Marsh concluded that Ceratosauria must be placed very near Archaeopteryx and its related groups.[3]

However, the idea of the Ceratosauria was soon contested by Marsh's rival, Edward Drinker Cope. Cope argued that the taxon was invalid.[4] The idea of the Ceratosauria would regain some support more than thirty years later when Gilmore argued in its favor in 1920. Despite Gilmore's support, few species were added to the group following World War I, and little emphasis was placed on it. In fact, the scientific communities most common interaction with Ceratosauria throughout much of the 20th century was the disputation of its existence, performed by the likes of Romer, Lapparent, Lavocat, Colbert, and Charig amongst others.

Ceratosauria's fortune changed in 1986 when Jacques Gauthier, in an attempt to clarify the evolution of birds, grouped the majority of theropods into either Ceratosauria or Tetanurae. In Ceratosauria, he placed the ceratosaurs and coelophysoids.[5] Gauthier's paper brought Ceratosauria's use back in vogue, and by the early 1990s, Abelisaridae had also been included under Ceratosauria. The triumvirate model of ceratosaurs, coelophysoids, and abelisaurids would go unchallenged until the early 2000s. Beginning at the turn of the millennium, a large number of paleontologists began excluding coelophysoids from Ceratosauria. This view is now widely held thanks to several similarities between Ceratosauria and Tetanurae not found in coelophysoids.

Current Phylogeny

Most paleontologists have postulated that Ceratosauria split off from other theropods in the late Triassic or early Jurassic. Despite this, no ceratosaurs have been discovered prior the middle Jurassic, and even in the middle Jurassic, species are sparse. Many scientists, such as Carrano and Sampson, have postulated the lack of specimens is due to a poor fossil record, rather than an indictment on the abundance of ceratosaurs at the time. A similarly large gap of specimens exist in the lower Cretaceous, particularly for Abelisaridae. Several recent discoveries of possible ceratosaurs have begun reshaping the phylogeny of Ceratosauria by filling in some of these gaps. Specifically, this has allowed paleontologists to begin altering the sub-groups inside Ceratosauria, in an attempt to find their most basal members.

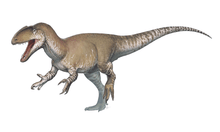

Currently, most paleontologists agree that Ceratosauria divides into two sub groups, Ceratosauridae and Abelisauroidea, with some variance as to which taxa are placed into basal polotomy.[2][6] Abelisauroidea is further divided into the Abelisauridae and Noasauridae, with Abelisauridae, including Carnotaurinae. Recently, Rauhut and Carrano have placed Elaphrosaurinae inside Noasauridae while simultaneously moving the previous noasaurs into Noasaurinae.[6] Into their new Noasauridae, they have uniquely included Deltadromeus and Limusaurus.

The oldest known ceratosaur currently described is Berberosaurus liassicus at 185 Ma. Some paleontologists believe that Berberosaurus liassicus, is the most basal ceratosaur currently discovered as well.[7] The placement of B. liassicus has been a topic for debate, with some considering it an abelisaur, while others classifying as a basal polotomy.

The following cladogram follows an analysis by Diego Pol and Oliver W. M. Rauhut, 2012.[2]

| Ceratosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A different conclusion was reached in a 2017 paper on Limusaurus ontogeny. The phylogenetics from the analysis with composite Limusaurus codings is shown below. Unlike other analyses, Noasauridae was placed more basal than Ceratosaurus, with the latter being within Abelisauridae by definition.[8]

| Ceratosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Anatomy

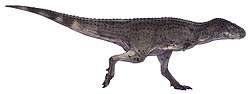

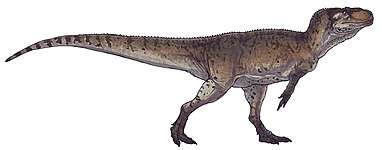

Some of the defining characteristics of Ceratosauria include an increase in height and ornamentation of the skull, as well as a shortening of the forelimbs. Likewise, ceratosaurs fused their ilium, ischium, and pubis together, as well as the astralagus and calcaneum.[4] For less derived members of the group, such as C. nasicornis, traits such as raising of the skull and shortening of the forelimbs were not as noticeable. The skull of C. nasicornis was rather similar to the basal theropod mold, with a distinguishing nasal crest to go along with lacrimal crests similar to the contemporary Allosaurus. C. nasicornis had larger teeth than Allosaurus, and some paleontologists postulate that it would have had a difficult time attacking larger prey. Abelisaurids, however, carried many of these defining traits to their extremes. Most abelisaurids had largely shortened forelimbs, with Carnotaurus having shrunk them further than any large theropod.[9] After analyzing the features of the newly discovered Rugops primus, Paul Sereno has postulated that many of these abelisaurid features may lend themselves to scavenging.[10] Despite the huge reduction in size, no taxa in Ceratosauria ever lost a digit or any critical elements of the forelimb. Some joint variation has also been observed in Ceratosauria, and it has been postulated that they may have had better shoulder mobility than other large theropods.[1]

Geography

Ceratosaurs appeared to have had a global population that diverged by the early Jurassic. However, they appear to have largely disappeared from Laurasia in the Cretaceous, with those few specimens that have been discovered having been possibly reintroduced from Gondwana.[11] No confirmed specimens of ceratosaurs in North America during the Cretaceous have been found.

Abelisaurids in particular had great success in Gondwana, particularly in the Cretaceous. Some Gondwana specimens have recently been found and dated to Late Jurassic, and possibly even the Middle Jurassic, greatly extending the Abelisaurid timeline. Some paleontologists have postulated that a large desert may have kept abelisaurids locked in southern Gondwana until the late Jurassic.[2] Whether correlation or causation, it has been largely observed that late Cretaceous ceratosaurs were found less in areas dominated by basal tetanurans (Africa) or coelosaurs (North America and Asia). The below phylogeny follows a simplified cladogram of Hendrickx et al. (2015), limited to Ceratosauria.

| Ceratosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diet

Ceratosaurs were theropods and thus carnivores, with one exception, Limusaurus inextricabilis was an herbivore with a toothless beak.[12] Ceratosaurus has been argued to have eaten a large amount of fish and other aquatic creatures, though this has been disputed by many paleontologists.[13] Tooth marks on large animals such as Allosaurus indicate that Ceratosaurus likely utilized scavenging often.[14] The interesting jaws of the abelisaurids have drawn mixed dietary predictions. One study on Carnotaurus found that its bite, thanks to its shortened skull, was suited for hunting small prey, thanks to a quick, but relatively weak bite.[15] On the other hand, other groups of paleontologists have found that the bite of Carnotaurus was relatively powerful, and more adept at hunting and wounding large prey.[16] Others have postulated its skull was built for scavenging. The debate over the eating habits of ceratosaurs is quite active, particularly recently with the increase in abelisaur discoveries.

See also

References

- Carrano, Matthew T.; Sampson, Scott D. (2008-01-01). "The Phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (2): 183–236. doi:10.1017/S1477201907002246. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 30068953.

- Diego Pol & Oliver W. M. Rauhut (2012). "A Middle Jurassic abelisaurid from Patagonia and the early diversification of theropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1804): 3170–5. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0660. PMC 3385738. PMID 22628475.

- Marsh, O. C. (1884). "On the united metatarsal bones of Ceratosaurus". American Journal of Science. s3-28 (164): 161–162. Bibcode:1884AmJS...28..161M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-28.164.161.

- ...)., Weishampel, David B. (1952-; Peter, Dodson; ...)., Osmólska, Halszka, (1930- (2007). The Dinosauria. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520242098. OCLC 493366196.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences. 8. 1986. ISSN 0885-4629.

- Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Carrano, Matthew T. (2016-11-01). "The theropod dinosaur Elaphrosaurus bambergi, from the Late Jurassic of Tendaguru, Tanzania". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 178 (3): 546–610. doi:10.1111/zoj.12425. ISSN 0024-4082.

- Allain, Ronan; Tykoski, Ronald; Aquesbi, Najat; Jalil, Nour-Eddine; Monbaron, Michel; Russell, Dale; Taquet, Philippe (2007-09-12). "An abelisauroid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Early Jurassic of the High Atlas Mountains, Morocco, and the radiation of ceratosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27 (3): 610–624. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[610:AADTFT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Wang, S.; Stiegler, J.; Amiot, R.; Wang, X.; Du, G.-H.; Clark, J.M.; Xu, X. (2017). "Extreme Ontogenetic Changes in a Ceratosaurian Theropod" (PDF). Current Biology. 27 (1): 144–148. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.10.043. PMID 28017609.

- Bonaparte, José; Novas, Fernando; Coria, Rodolfo (1990). "Carnotaurus sastrei Bonaparte, the horned, lightly built carnosaur from the Middle Cretaceous of Patagonia. Contributions in Science" (PDF). Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. 416: 1–42. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-29. Retrieved 2017-05-31.

- Sereno, Paul C.; Brusatte, Stephen L. (2008). "Basal Abelisaurid and Carcharodontosaurid Theropods from the Lower Cretaceous Elrhaz Formation of Niger". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (1): 15–46. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0102.

- Tortosa, Thierry; Buffetaut, Eric; Vialle, Nicolas; Dutour, Yves; Turini, Eric; Cheylan, Gilles (2014). "A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of southern France: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Annales de Paléontologie. 100 (1): 63–86. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2013.10.003.

- Xu, Xing; Clark, James M.; Mo, Jinyou; Choiniere, Jonah; Forster, Catherine A.; Erickson, Gregory M.; Hone, David W. E.; Sullivan, Corwin; Eberth, David A. (2009-06-18). "A Jurassic ceratosaur from China helps clarify avian digital homologies" (PDF). Nature. 459 (7249): 940–944. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..940X. doi:10.1038/nature08124. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 19536256.

- J., Currie, Philip; B., Koppelhus, Eva; A., Shugar, Martin; L., Wright, Joanna (2004). Feathered dragons : studies on the transition from dinosaurs to birds. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253343734. OCLC 895411495.

- "Prey bone utilization by predatory dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic of North America, with comments on prey bone use by dinosaurs throughout the Mesozoic (PDF Download Available)". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2017-05-31.

- Mazzetta, Gerardo V.; Cisilino, Adrián P.; Blanco, R. Ernesto; Calvo, Néstor (2009-09-12). "Cranial mechanics and functional interpretation of the horned carnivorous dinosaur Carnotaurus sastrei". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 822–830. doi:10.1671/039.029.0313. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Kenneth., Carpenter (2005). The carnivorous dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253345394. OCLC 895411496.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ceratosauria. |