Royal Commission on London Traffic

The Royal Commission on London Traffic was a Royal commission established in 1903 with a remit to review and report on how transport systems should be developed for London and the surrounding area. It produced a report in eight volumes published in 1905 and made recommendations on the character, administration and routing of traffic in London.

Establishment

The Royal Commission on London Traffic was established on 10 February 1903. It had 13 commissioners and was chaired by Sir David Barbour. Its secretary was Lynden Macassey and the other commissioners were:[1]

|

|

Remit

The Commission's remit was to report on London's traffic arrangements and:

(a) as to measures which the Commission deem most effectual for the improvement of the same by the development and inter-connexion of Railways and Tramways on, or below, the surface; by increasing the facilities for other forms of mechanical locomotion; by better provision for the organization and regulation of vehicular and pedestrian traffic, or otherwise;

(b) as to the desirability of establishing some authority or tribunal to which all schemes of Railway or Tramway construction of a local character should be referred, and the powers which it could be advisable to confer on such a body.[3]

The area of the Commission's scope covered the Metropolitan Police District,[lower-alpha 2] an area of 692.84 square miles (1,794.4 km2) and a population of more than 6.5 million in 1901.[3] In its report the Commission described this as "Greater London" and the urban developed area at its centre as "the Metropolis". The area beyond the Metropolis was described as "Extra London".[4]

Investigation

The Commission held 112 meetings and interviewed 134 witnesses. Members of the Commission carried out fact-finding visits to New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington in 1903 and to Vienna, Budapest, Prague, Cologne, Dresden, Berlin, Brussels and Paris in 1904.[5]

An Advisory Board of three engineers was appointed to give the Commission technical advice. The board consisted of Sir John Wolfe Barry (also a member of the Commission), Sir Benjamin Baker, former President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and William Barclay Parsons, Chief Engineer to the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners of the City of New York.[6]

Report and recommendations

The Commission's Report, Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Means of Locomotion and Transport in London, was published in eight volumes on 17 July 1905.[7][lower-alpha 3]

The Report examined the historic development of road, rail and tram transportation and the current condition. It made recommendations for improvements to roads within London's central area and arterial roads; for improvements in tramways including new routes and for improvements in railways of all types including their connections to one another. Recommendations were made as on road traffic regulations and the Commission recommended the establishment of a Traffic Board to manage traffic developments in the Greater London area and carry out preliminary reviews of bills for traffic schemes before they were submitted to parliament.[9]

Roads

The Report identified that road traffic was constrained by the narrowness of many of London's roads which reflected the historic development of the city.[10][lower-alpha 4]

The Report recommended that a comprehensive plan should be developed to improve road provision and routing to be carried out over the long term and that new roads should be constructed to standard widths depending on their importance and that existing main routes should be widened when possible.[lower-alpha 5]

Recommended road improvements

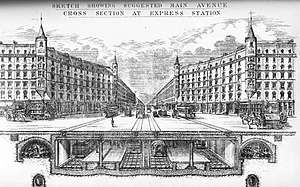

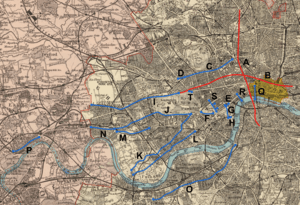

The Advisory Board recommended construction of two "Main Avenues". These would be 140 feet (43 m) wide between buildings with four tram lines on the road and four railway lines in a sub-surface tunnel immediately beneath. Two of the tram lines and two of the railway lines would be for express services and service tunnels would be provided for utilities beneath the 23-foot (7.0 m) wide pavements.[12] The Main Avenues would connect areas on the outskirts of the main urban area and tramways and railway lines would be connected to these at both ends:[13]

- A: New Main Avenue, West to East – Bayswater Road to Whitechapel running from Victoria Gate of Hyde Park, through Portman Square, Russell Square, London Wall to the junction of Commercial Road and Whitechapel High Street.[12]

- B: New Main Avenue, North to South – Holloway to Elephant & Castle running via Caledonian Road and Gray's Inn Road and including a new bridge over the River Thames to the west of Blackfriars Bridge.[12]

The Main Avenues would cross at Gray's Inn Road.[12] Definitive routes were not proposed, but the Report recognised that the scale of the projects would require them to be carried out as a complete exercise. The cost of both Main Avenues was estimated to be £30 million (equivalent to approximately £3.25 billion today)[14] for the 9 miles (14 km) of new roads, tramways and railways.[13]

Other main road improvements recommended by the Advisory Board were:[15]

- C: Widening of Marylebone Road and Euston Road.

- D: Construction of a new street between Marylebone Road and Edgware Road.

- E: Extension of The Mall to Charing Cross (now the north end of Whitehall).

- F: Widening of Constitution Hill.

- G: Widening of Princes Street, Westminster and construction of a new street along the east side of St James's Park to Waterloo Place and Duke of York's Column.

- H: Widening of Broad Sanctuary, Westminster.

- I: Widening of Uxbridge Road and Bayswater Road.

- J: Widening of Hammersmith Road and Kensington Road.

- K: Widening of Fulham Road and Brompton Road.

- L: Widening of King's Road, Chelsea.

- M: Extension of West Cromwell Road.

- N: Widening of King Street, Hammersmith.

- O: Widening of Wandsworth Road, Lavender Hill, St John's Hill and Wandsworth High Street from Lambeth to Putney.

- P: Widening of Brentford High Street or construction of a new street.[lower-alpha 6]

- Q: Viaduct from Blackfriars Bridge to Farringdon Street. The viaduct would start in the centre of the bridge and run to just south of Holborn Viaduct to relieve congestion at the north end of the bridge and at Ludgate Circus.[lower-alpha 7]

- R: Viaduct from Waterloo Bridge to Wellington Street to segregate traffic from the bridge from east-west traffic along Strand.[lower-alpha 8]

- S: Construction of a new street from Berkeley Square to the Mall via the eastern side of Green Park with branches to connect to Jermyn Street and Pall Mall.[lower-alpha 9]

- T: Widening Marble Arch between Edgware Road and Park Lane.

The Report indicated that there were many other roads and junctions that required improvements including for main roads leading out of London. For the latter the Report recommended that this should be a responsibility for the Traffic Board to report on when established.[18] Although it did not make any recommendations on the subjects, the Report noted that submissions made to the Commission, included suggestions for "making roads in different directions out of London", "constructing a circular road about 75 miles in length at a radius of 12 miles from St Paul's", "providing alternative streets parallel to crowded thoroughfares, and new streets" and "removing factories from London".[10]

Tramways

The Report identified that the existing tramway systems were fragmented and lacked connections.[19][lower-alpha 10] Compared to other British cities, Greater London's tramway systems were significantly under-developed.[19][lower-alpha 11] The report criticised the London County Council's (LCC's) policy of refusing to allow the privately owned tramways operating outside the county's boundary to connect to and operate over its municipally owned system within. It also criticised the failure of the County to join its three separate systems together and to allow trams in the central areas of the City of London and the West End.[20][lower-alpha 12]

The Report recommended that interconnection of the existing tramways be undertaken and recommended construction of many new routes in areas not served and that through running of services between different operators be allowed. The Report recommended that vetos held by the London County Council and the municipal boroughs within it over the construction of new tramways should be abolished.[21][lower-alpha 13]

The Advisory Board recommended the construction of 23 new tramways to connect the separate systems and bring trams to unserved areas. It estimated that the cost of constructing double line tramways was four to five per cent of the cost of constructing a cut and cover line such as the Metropolitan Railway or 13 to 17 per cent of the cost of a deep-level tube line such as the Central London Railway.[23][lower-alpha 14]

Recommended tramway improvements

The new routes recommended by the Advisory Board were:[26]

- Route 1: Across Hammersmith Bridge – to connect the London County Council Tramways' (LCCT's) planned terminus at the north end to the London United Tramways' (LUT's) terminus at the south end.

- Route 2: Hammersmith to Knightsbridge – Hammersmith Broadway running via Hammersmith Road, Kensington Road and Knightsbridge to the north end of Sloane Street.

- Route 3: Knightsbridge to Aldgate – continuing Route 2 and running below ground in a subway from the junction of Albert Gate and Knightsbridge via Hyde Park Corner, Piccadilly, Coventry Street, Leicester Square, King William Street, Strand, Fleet Street, Ludgate Hill, Cheapside, Cornhill, Leadenhall Street to the LCCT's terminus in Aldgate High Street.[lower-alpha 15]

- Route 4: Fulham and Brompton Road – running from a junction with the LCCT's planned terminus in Fulham Palace Road and Fulham High Street via Fulham Road and Brompton Road and ending at a junction with Routes 2 and 3 at the north end of Sloane Street.

- Route 5: Grosvenor Place and Hyde Park – running from the LCCT's terminus in Vauxhall Bridge Road via Victoria Street, Grosvenor Gardens, Grosvenor Place and Hyde Park to the southern end of Edgware Road. The section from Grosvenor Gardens to Edgware Road would run in a subway, part of which was to be under Hyde Park.

- Route 6: Edgware Road and Maida Vale – running from a junction with Route 5 at Marble Arch via Edgware Road, Maida Vale, Kilburn High Road to a junction with the Middlesex County Council's Light Railways' terminus at Cricklewood.

- Route 7: Harrow Road – running from a junction with the Harrow Road and Paddington Tramways' (HR&PT's) terminus in Harrow Road via Harrrow Road, Westbourne Terrace and Bishops Road to a junction with Routes 6 and 22 in Edgware Road.

- Route 8: Cambridge Avenue – running from a junction with the HR&PT's terminus in Cambridge Road via Cambridge Avenue to a junction with Route 6 in Edgware Road.

- Route 9: Uxbridge Road and Bayswater Road – running from the LUT's terminus in Uxbridge Road at Shepherd's Bush via the Holland Park Avenue, Notting Hill Gate and Bayswater Road to connect to Route 5 at Marble Arch.

- Route 10: Westminster Bridge and Victoria Embankment – running from the LCCT's terminus in Westminster Bridge Road via Westminster Bridge, Victoria Embankment to a junction with the LCCT's planned Kingsway tramway subway and Route 11 at the north end of Waterloo Bridge.

- Route 11: Waterloo Bridge and Blackfriars Bridge – running from a junction with Route 10 at the north end of Waterloo Bridge via the Victoria Embankment to a junction with Routes 12 and 13 at the north end of Blackfriars Bridge.

- Route 12: Queen Victoria Street and Southwark Bridge – running from a junction with Route 11 at the north end of Blackfriars Bridge via Queen Victoria Street, Cannon Street, Queen Street and Southwark Bridge to the LCCT's terminus in Southwark Bridge Road.

- Route 13: New Bridge Street and Farringdon Street – running from the LCCT's terminus in Blackfriars Road across Blackfriars Bridge and then on a viaduct above New Bridge Street to Farringdon Street, Farringdon Road and Clerkenwell Road to a junction with the LCCT's terminus in Theobald's Road

- Route 14: Holborn and Charterhouse Street – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus at the southern end of Gray's Inn Road via Holborn, Holborn Circus and Charterhouse Street to a junction with Route 13 in Farringdon Road.

- Route 15: York Road, Stamford Street and Southwark Street – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus in Westminster Bridge Road via York Road, Stamford Street and Southwark Road to a junction with the LCCT's terminus in Southwark Bridge Road. A branch along Waterloo Road would connect with the LCCT's terminus there.

- Route 16: Tower Subway – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus at Leman Street then in a tunnel under the River Thames on the east side of St Katharine Docks to a junction with the LCCT's terminus at the south end of Tower Bridge.[lower-alpha 16]

- Route 17: Tottenham Court Road and Whitehall – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus at the southern end of Hampstead Road via Tottenham Court Road, Charing Cross Road, the east side of Trafalgar Square, Charing Cross, Whitehall, Parliament Street and Bridge Street to a junction with Route 10 at the west end of Westminster Bridge.

- Route 18: Moorgate, Liverpool Street and Norton Folgate – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus at South Place via Finsbury Pavement, Finsbury Circus, Liverpool Street and Bishopsgate to a junction with the LCCT's terminus in Norton Folgate.

- Route 19: Aldersgate Street to Post Office – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus near Charterhouse Square and then in a subway under Aldersgate Street and St. Martin's Le Grand to a terminus near the General Post Office.

- Route 20: King's Road, Chelsea and Buckingham Palace Road – running from a junction with the LCCT's terminus in Fulham High Street at the north end of Putney Bridge via New King's Road, King's Road, Sloane Square, Lower Sloane Street, Pimlico Road and Buckingham Palace Road to a junction with Route 4 at the junction of Victoria Street and Grosvenor Gardens.

- Route 21: Victoria Street, Westminster – running from a junction with Route 5 at the north end of Vauxhall Bridge Road via Victoria Street, Broad Sanctuary and Parliament Square to a junction with Route 17 in Parliament Street.

- Route 22: Marylebone Road and Euston Road – running from a junction with Route 7 at Edgware Road via a proposed new road, Marylebone Road, Euston Road to a junction with the LCCT's terminus at King's Cross station.

- Route 23: Finchley Road – running from a junction with Route 22 at Upper Baker Street via Park Road, Wellington Road and Finchley Road to a junction with the Middlesex County Council's Light Railways' planned terminus at Childs Hill.

With the exception of Route 8 and the southern end of Route 1 and the northern parts of Routes 6 and 23 which crossed the county boundary, all of the routes were in the County of London.

Railways

The Report noted that the Commission considered that the purpose of railways was to bring passengers from the residential districts into the urban centre. A survey of traffic usage calculated the estimated total number of journeys for 1903 as 310,662,501 (27,364,209 from the west, 51,838,742 from the north, 89,224,298 from the east, 75,487,731 from the south-east and 66,717,521 from the south-west).[27][lower-alpha 17]

Within the urban centre, trams and buses were considered to be the most convenient form of mass transport.[29] The Commission excluded railway goods traffic from its consideration noting only that the distribution of most retail goods within the centre on London was by road as the railways could not compete due to convenience and cost. A desire was expressed that this was better organised to reduce its contribution on traffic congestion, but no solution was proposed.[30]

The Report noted that most suburban and long distance passengers arrived at the same termini and that government policy of prohibiting railways from entering central London meant that the many railway companies then in operation had developed a messy network of lines in the periphery to connect to one another.[31][lower-alpha 18][lower-alpha 19] The Report noted that the Commission considered the way in which the termini had been located around the central area and the way that the railway companies' lines had been connected to one another were the main causes of deficiencies in the railways.[34]

The Commission set itself three questions with regard to the provision of railways: were additional railways needed in the London area and should they be deep-level, sub-surface or surface lines; were the existing suburban rail services sufficient and was special encouragement or assistance needed for future railway construction.[34][35]

Recommended railway improvements

The Report noted that deep-level underground lines under construction (Baker Street and Waterloo Railway, Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway and Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway) or planned would provide additional connections with many of the termini not already connected which would facilitate passengers' onward journeys into the central area. It considered that these new lines would mitigate many of the existing problems, but recommended that connections between north-south and east-west lines be provided and that connections between the suburban networks on the east and west sides of the central area be improved including by way of the Main Avenues proposed for the road and tram improvements. The only new deep-level line recommended was from Victoria station northwards to alleviate what was expected to remain a problem for passengers travelling into the central area. The Report recommended that a north-south line be provided from Victoria to Marble Arch where the approved but unbuilt North West London Railway was to terminate.[35][36][lower-alpha 20]

To improve east-west connections, the Advisory Board recommended connecting Hammersmith to the City of London via Kensington, Piccadilly and the Strand either by an underground railway or as a tramway (Routes 2 and 3 above).[40][lower-alpha 21]

The other main recommendation was that construction of railways in London should continue to be funded by private enterprise, but that parliament should provide a favourable system of procedures to encourage bills to be promoted as easily as possible.[41] The commission also recommended that parliament should avoid imposing additional financial burdens on the proposals, such as the cost of reconstructing roads and should allow railway companies to buy land around their proposed new extensions in order to benefit from the increase in land prices and to profit from the new services they provide.[42]

Traffic Board

The Report identified the need for a unified system for the "general control of measures affecting locomotion and transport in London", but considered it inappropriate for any of the existing authorities within the region to fulfil this role or for it to be established as a committee composed of representatives of the multiple authorities. It, therefore, recommended that a new authority, a "Traffic Board", be established. The Report recommended that the board partially replace the existing parliamentary process of scrutinising private bills for transport proposals in the Greater London area. The Report's recommendation was that the board should have the powers for:[43]

- Control of traffic

- Regulation of the opening up of streets

- Removal of obstructions to traffic

- Provision of new railway lines and tramways

- Monitoring of road maintenance by local authorities and identification of failures

- Preliminary examination and reporting on of private bills before submission to Parliament[lower-alpha 22]

- Hold annual sessions and produce an annual report but be generally in continuous operation

With regards to the construction of new transport systems, The Report considered that the Traffic Board might function in a similar supervisory capacity to the Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners of New York or the Rapid Transit Commission of Boston.[44]

The Report recommended that The Traffic Board should have a chairman and two to three other members. Because of the small number of members, The Report considered nomination by the local authorities within the Greater London area to be inappropriate as not all would be represented. Therefore the board's members should be directly appointed by the government.[45]

The costs of the board should be covered by a fees and a levy on the local authorities within the Greater London area paid from the local rates.[46]

Minority reports

Two of the Commission's members issued their own reports; a third member issued an additional recommendation. Bartley felt that the main report did not go far enough in its recommendations and he wanted the full adoption of the Advisory Board's recommendation for the construction of a pair of grand avenues. Dimsdale, rejected the main report's recommendation for tram routes in central London. Gibb's additional recommendation was that part of the route of the then under construction Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway should be merged with a planned route from the Central London Railway to form a looping line.[47][lower-alpha 23]

Afterwards

The Report's recommendations were acted on in a limited manner. The recommendation for an all-encompassing Traffic Board was not adopted, although the London and Home Counties Traffic Advisory Committee was established in 1924 to oversee road traffic in the London Traffic Area.

Amongst the recommendations for road improvements, the new east-west and north-south Main Avenues were not constructed. A number of the proposed road improvements were carried out:

- Marylebone Road was extended west to a new junction with Edgware Road in the 1960s in conjunction with the construction of the Marylebone Flyover and the Westway

- The Mall was extended to Charing Cross in 1912 when Admiralty Arch was constructed

- The western end of Constitution Hill was rearranged when Hyde Park Corner was replanned in the 1960s for the Hyde Park Underpass

- The extension of West Cromwell Road and widening of King Street, Hammersmith were dealt with in the 1960s by the construction of the new A4 road starting at West Cromwell Road, including widening of Talgarth Road and construction of the Hammersmith Flyover

- The widening or replacement of Brentford High Street was dealt with in the 1920s by the construction of the Great West Road starting at Chiswick

- Instead of a viaduct from Waterloo Bridge to Wellington Street the disused Kingsway tramway subway was converted in 1964 to the Strand Underpass connecting northbound traffic from Waterloo Bridge to Kingsway

- Marble Arch was widened in the 1960s when Park Lane was widened

The tramway system was gradually improved into a more integrated system. By the mid-1910s, the three independent tram companies were owned by the London and Suburban Traction Company which was jointly owned by the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) and British Electric Traction.

Review and approval of all new railway lines or extensions to existing lines continued to be carried out by parliament. The three underground lines under construction at the time the Commission sat opened in 1906 and 1907 and were owned, along with the District Railway, by the UERL. From 1913, the UERL also controlled the Central London Railway and the City and South London Railway. Extensions of all of the lines were proposed and built during the 1910s to 1930s. From 1910, the UERL also owned the largest bus company in London, the London General Omnibus Company.

Consolidation of the mainline railway companies continued and under the Railways Act 1921 they were merged into the Big Four in 1923.[lower-alpha 24] Under the London Passenger Transport Act 1933, the UERL, the Metropolitan Railway, the municipal tram operators and all bus operators in the London region were amalgamated under the single control of the London Passenger Transport Board in 1934.

Further studies that considered the improvement of traffic in London were carried out. Sir Charles Bressey with Sir Edwin Lutyens considered road improvements in The Highway Development Survey (1938) and Sir Patrick Abercrombie's County of London Plan (1943) and Greater London Plan (1944) included recommendations on rail and road transport.

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- Earl Cawdor resigned from the Commission in March 1905 to became First Lord of the Admiralty.[2]

- The Metropolitan Police District included the City of London, County of London, and all civil parishes in the counties of Essex, Kent, Hertfordshire, Middlesex and Surrey that were completely within 15 miles or which were partly within 12 miles of Charing Cross.

- The volumes of the report were titled:[8]

I – Report of the Royal Commission on London Traffic with Index and Plans

II – Minutes of Evidence Taken by the Royal Commission on London Traffic with Index and Digest

III – Appendices to the Evidence Taken by the Royal Commission on London Traffic with Index

IV – Appendices to the Report of the Royal Commission on London Traffic with Index

V – Maps and Diagrams furnished to or prepared by the Royal Commission on London Traffic with Index

VI – Maps and Diagrams furnished to the Royal Commission on London Traffic with Index

VII – Report to the Royal Commission on London Traffic by the Advisory Board of Engineers with Index

VIII – Appendix to the Report to the Royal Commission on London Traffic by the Advisory Board of Engineers with Index. - The Report noted that average road speeds in quiet periods were 8 miles per hour (13 km/h) which reduced to 4.5 miles per hour (7.2 km/h) at busy times.[10]

- Measured between buildings including footpaths on each side, the standard road widths proposed were:[11]

"Main Avenues": 140 feet (43 m)

"First-class Arterial Streets": 100 feet (30 m)

"Second-class Streets": 80 feet (24 m)

"Third-class Streets": 60 feet (18 m)

"Fourth-class Streets": 40–50 feet (12–15 m) - The Report made particular note that Brentford High Street was the main road out of London to Slough, Reading and the west of England and that the width of the carriageway was just 19 feet (5.8 m) wide.[16]

- The cost was estimated to be £700,000 (equivalent to approximately £75.7 million today).[14][17]

- The cost was estimated to be £325,000 (equivalent to approximately £35.2 million today).[14][17]

- The section from Berkeley Square to Piccadilly would have required the purchase of parts of the gardens of Lansdowne House and Devonshire House and possibly the demolition of the latter.

- At the end of 1904, Greater London had 203.33 miles (327.23 km) of tramways in operation and 146.85 miles (236.33 km) approved.[19]

- The comparison was made on an inhabitant per mile basis. Greater London had 33,661 inhabitants per mile compared to Manchester with 8,937 and Glasgow with 14,216.[19]

- The report identified that the time taken to turn trams around at their termini reduced the potential capacity of the system by about 50% and caused substantial road congestion.[20]

- The London County Council and the municipal boroughs could each veto the others plans for new tramways and also plans by private operators.[22]

- The Advisory Board's estimations of costs for underground railways were very approximate: "a million a mile" for cut and cover tunnels under busy roads or from "£250,000 to £300,000 per mile" for deep-level lines. The latter was only on the basis that "stations were few in number, the land obtained for nothing and exceptional facilities granted for the work". The cost of constructing a double line of tramways was reported by the London County Council to be £39,512 per mile for routes with power proved from overhead wires and £52,602 per mile for routes with power provided from conduit in the roadway.[24] For tramways running in subways below streets, the cost of construction was estimated to be comparable to that of a cut and cover railway tunnel rising to as much as £1 million in specific locations.[25]

- Although included in the recommendations of the Advisory Board, the construction of the Route 3 tramway from Knightsbridge (Albert Gate) to Aldgate as a subway was considered too expensive to be practical, particularly as the Great Northern, Piccadilly & Brompton Railway (now part of the Piccadilly line) was under construction between Knightsbridge and Leicester Square.[25]

- The cost of constructing the Route 16 tramway in a tunnel under the river was considered not justified whilst expenditure on other proposals was required.[25]

- Liverpool Street station was the busiest of all of the stations with an estimated 65,299,450 passengers.[28]

- At the time of the report, London had 13 mainline railway termini served by ten railway companies:

1. Fenchurch Street (Great Eastern Railway and London, Tilbury and Southend Railway)

2. Liverpool Street (Great Eastern Railway)

3. King's Cross (Great Northern Railway)

4. St Pancras (Midland Railway)

5. Euston (London and North Western Railway)

6. Marylebone (Great Central Railway)

7. Paddington (Great Western Railway)

8. London Bridge (London, Brighton and South Coast Railway)

9. Cannon Street (South Eastern and Chatham Railway)

10. Holborn Viaduct (South Eastern and Chatham Railway)

11. Charing Cross (South Eastern and Chatham Railway)

12. Waterloo (London and South Western Railway)

13. Victoria (London, Brighton and South Coast Railway and South Eastern and Chatham Railway).[31]

Additionally, Broad Street served as the terminus of the suburban North London Railway. - The prohibition on railways entering the central area was made in 1846 following recommendations of the Royal Commission investigation into Metropolitan Railway Termini.[32][33] The only exception to this was the line from Blackfriars to Farringdon via the Snow Hill tunnel.

- The North West London Railway had obtained parliamentary approval in 1899 for a line from Cricklewood to Marble Arch.[37] In 1903, the company submitted a bill for an extension of its route from Marble Arch to Victoria, which was postponed during the Commission's investigation and was resubmitted and approved in 1906.[38] The line was never built. Benjamin Baker, who was a member of the Advisory Board, was a promoter of the company.[39]

- Several competing proposals for underground railway lines had been presented to parliament for lines connecting these points including the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway's line, which began construction in 1902 and opened in 1906.

- The Traffic Board was to make its own decision as to how extensive this examination and reporting should be.

- Dimsdale and Gibb signed the main report, Bartley did not.[2]

- The Big Four were the Great Western Railway, London, Midland and Scottish Railway, London and North Eastern Railway and Southern Railway.

References

- Barbour 1905, pp. iii–v.

- Barbour 1905, p. 105.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 222–23.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 3 & 50.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 222.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 229.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 222 & 223.

- Barbour 1905, p. vi.

- Barbour 1905, p. 99.

- Barbour 1905, p. 33.

- Barbour 1905, p. 34.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 230.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 35–36.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 37–38.

- Barbour 1905, p. 37.

- Barbour 1905, p. 38.

- Barbour 1905, p. 40.

- Barbour 1905, p. 41.

- Barbour 1905, p. 42.

- Barbour 1905, p. 54.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 52–54.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 44–47.

- Barbour 1905, p. 44.

- Barbour 1905, p. 48.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 45–47.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 64-65.

- Barbour 1905, p. 65.

- Barbour 1905, p. 55.

- Barbour 1905, p. 57.

- Barbour 1905, p. 59.

- Simpson 2003, p. 7.

- "Metropolitan Railway Termini". The Times (19277). 1 July 1846. p. 6. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Barbour 1905, p. 63.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 225.

- Barbour 1905, p. 68.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 79-82.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, pp. 220-221, 266.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 78.

- Barbour 1905, p. 69.

- Barbour 1905, p. 70.

- Barbour 1905, p. 71.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 98-100.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 100-101.

- Barbour 1905, pp. 101-102.

- Barbour 1905, p. 102.

- Badsey-Ellis 2005, p. 226.

Bibliography

- Badsey-Ellis, Antony (2005). London's Lost Tube Schemes. Capital Transport. ISBN 185414-293-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barbour, David; et al. (1905). Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Means of Locomotion and Transport in London. I. His Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 26 December 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simpson, Bill (2003). A History of the Metropolitan Railway. Volume 1: The Circle and Extended Lines to Rickmansworth. Lamplight Publications. ISBN 1-899246-07-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)