Brno

Brno (/ˈbɜːrnoʊ/ BUR-noh,[4] Czech: [ˈbr̩no] (![]()

Brno | |

|---|---|

From top: The Liberty Square, Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, Lužánky Park, Villa Tugendhat, Ignis Brunensis, Brno Exhibition Centre, Špilberk Castle | |

Flag .svg.png) Coat of arms Logo | |

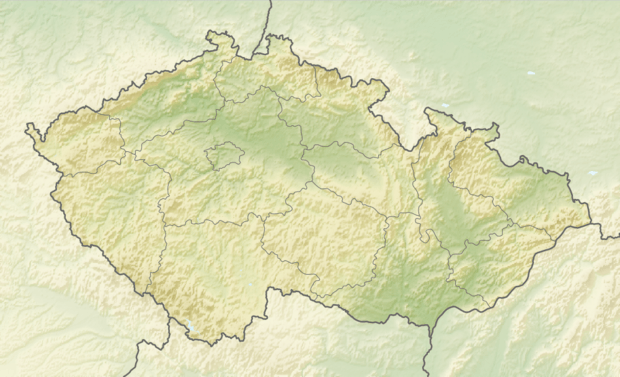

Brno Location in the Czech Republic | |

| Coordinates: 49°12′N 16°37′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | South Moravian |

| District | Brno-City |

| Founded | ca. 1000[1] |

| Administrative divisions | Bohunice, Bosonohy, Bystrc, Centre, Černovice, Chrlice, Ivanovice, Jehnice, Jundrov, Kníničky, Kohoutovice, Komín, Královo Pole, Lesná, Líšeň, Maloměřice and Obřany, Medlánky, North, Nový Lískovec, Ořešín, Řečkovice and Mokrá Hora, Slatina, South, Starý Lískovec, Tuřany, Útěchov, Vinohrady, Žabovřesky, Žebětín, Židenice |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Markéta Vaňková (ODS) |

| Area | |

| • Statutory city | 230.19 km2 (88.88 sq mi) |

| • Land | 225.73 km2 (87.15 sq mi) |

| • Water | 4.46 km2 (1.72 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,170 km2 (1,220 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 237 m (778 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 501 m (1,644 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 190 m (620 ft) |

| Population (2020-01-01[3]) | |

| • Statutory city | 381,346 |

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,300/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 605,988 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 600 00 – 650 00 |

| Area code(s) | 00420 5 |

| Website | www |

Brno is the former capital city of Moravia and the political and cultural hub of the South Moravian Region. It is the centre of the Czech judiciary, with the seats of the Constitutional Court, the Supreme Court, the Supreme Administrative Court, and the Supreme Public Prosecutor's Office, and a number of state authorities, including the Ombudsman,[6] and the Office for the Protection of Competition.[7] Brno is also an important centre of higher education, with 33 faculties belonging to 13 institutes of higher education and about 89,000 students.[8]

Brno Exhibition Centre ranks among the largest exhibition centres in Europe.[9] The complex opened in 1928 and established the tradition of large exhibitions and trade fairs held in Brno.[10] Brno hosts motorbike and other races on the Masaryk Circuit, a tradition established in 1930, in which the Road Racing World Championship Grand Prix is one of the most prestigious races.[11] Another cultural tradition is an international fireworks competition, Ignis Brunensis,[12] that attracts tens of thousands of daily visitors.[13]

The most visited sights of the city include the Špilberk castle and fortress and the Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul on Petrov hill, two medieval buildings that dominate the cityscape and are often depicted as its traditional symbols. The other large preserved castle near the city is Veveří Castle by Brno Reservoir.[14][15][16] Another architectural monument of Brno is the functionalist Villa Tugendhat which has been included on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.[17] One of the natural sights nearby is the Moravian Karst. The city is a member of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network and has been designated as a "City of Music" in 2017.[18]

Names

The etymology of the name Brno is disputed. It might be derived from the Old Czech brnie 'muddy, swampy.'[19] Alternative derivations are a Slavic verb brniti (to armour or to fortify) or a Celtic language spoken in the area before it was overrun by Germanic peoples and later Slavic peoples (he last theory would make it cognate with other Celtic words for hill, such as the Welsh word bryn).

Throughout its history, Brno's locals also referred to the town in other languages, including Brünn in German, ברין (Brin) in Yiddish and Bruna in Latin. The city was also referred to as Brunn (/brʌn/)[20] in English, but that usage is not common today.[21]

The asteroid 2889 Brno was named after the city, as well as the Bren light machine gun (Brno + Enfield), one of the most famous weapons of World War II.

History

The Brno basin has been inhabited since prehistoric times,[22] but the town's direct predecessor was a fortified settlement of the Great Moravian Empire known as Staré Zámky, which was inhabited from the Neolithic Age until the early 11th century.[23]

In the early 11th century Brno was established as a castle of a non-ruling prince from the House of Přemyslid,[22] and Brno became one of the centres of Moravia along with Olomouc and Znojmo. Brno was first mentioned in Cosmas' Chronica Boëmorum dated to the year 1091, when Bohemian king Vratislav II besieged his brother Conrad at Brno castle.[24]

In the mid 11th century, Moravia was divided into three separate territories; each had its own ruler, coming from the Přemyslids dynasty, but independent of the other two, and subordinated only to the Bohemian ruler in Prague. The seats of these rulers and thus the "capitals" of these territories were the castles and towns of Brno, Olomouc, and Znojmo. In the late 12th century, Moravia began to reunify, forming the Margraviate of Moravia. From then until the mid of the 17th century, it was not clear which town should be the capital of Moravia. Political power was divided between Brno and Olomouc, but Znojmo also played an important role. The Moravian Diet (cz: Moravský Zemský sněm), the Moravian Land Tables (cz: Moravské Zemské desky), and the Moravian Land Court (cz: Moravský Zemský soud) were all seated in both cities at once. However, Brno was the official seat of the Moravian Margraves (rulers of Moravia),[25] and later its geographical position closer to Vienna also became important. Otherwise, until 1642 Olomouc had a larger population than Brno, and it was the seat of the only Roman Catholic diocese in Moravia.

In 1243 Brno was granted the large and small city privileges by the King, and thus it was recognized as a royal city. In 1324 Queen Elisabeth Richeza of Poland founded the current Basilica of the Assumption of Our Lady which is now her final resting place.[26] In the 14th century, Brno became one of the centres for the Moravian regional assemblies, whose meetings alternated between Brno and Olomouc.[22] These assemblies made political, legal, and financial decisions. Brno and Olomouc were also the seats of the Land Court and the Moravian Land Tables, thus they were the two most important cities in Moravia. From the mid 14th century to the early 15th century the Špilberk Castle had served as the permanent seat of the Margraves of Moravia (Moravian rulers); one of them was elected the King of the Romans. Brno was besieged in 1428 and again in 1430 by the Hussites during the Hussite Wars. Both attempts to conquer the city failed.

17th century

In 1641, in the midst of the Thirty Years' War, the Holy Roman Emperor and Margrave of Moravia Ferdinand III ordered the permanent relocation of the diet, court, and the land tables from Olomouc to Brno, as Olomouc's Collegium Nordicum made it one of the primary targets of Swedish armies.[27] In 1642 Olomouc surrendered to the Swedish army, which then stayed there for 8 years.[note 1] Meanwhile, Brno, as the only Moravian city which under the leadership of Jean-Louis Raduit de Souches succeeded in defending itself from the Swedes under General Lennart Torstenson, served as the sole capital of the state (Margraviate of Moravia). After the end of the Thirty Years' War (1648), Brno retained its status as the sole capital. This was later confirmed by the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II in 1782, and again in 1849 by the Moravian constitution.[note 2] Today, the Moravian Land Tables are stored in the Moravian Regional Archive, and they are included among the national cultural sights of the Czech Republic.[28]

During the 17th century Špilberk Castle was rebuilt as a huge baroque citadel.[25] Brno was besieged by the Prussians in 1742 under the leadership of Frederick the Great, but the siege was ultimately unsuccessful. In 1777 the bishopric of Brno was established; Mathias Franz Graf von Chorinsky Freiherr von Ledske was the first Bishop.[22][note 3]

19th century

In December 1805 the Battle of Austerlitz was fought near the city; the battle is also known as the "Battle of the Three Emperors". Brno itself was not involved with the battle, but the French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte spent several nights here at that time and again in 1809.[29][30]

In 1839 the first train arrived in Brno from Vienna; this was the beginning of rail transport in what is now the Czech Republic.[31] In the years 1859–1864 the city fortifications were almost completely removed. In 1869 a horsecar service started to operate in Brno; it was the first tram service in what would later become the Czech Republic.[32]

Gregor Mendel conducted his groundbreaking experiments in genetics while he was a monk at St. Thomas's Abbey in Brno in the 1850s.

20th century and Greater Brno

Around 1900 Brno, which until 1918 consisted in administrative terms only of the central city area, had a predominantly German-speaking population (63%), as opposed to the suburbs, which were predominantly Czech-speaking.[33] Life in Brünn/Brno was therefore bilingual, and what was called in German "Brünnerisch" was a mixed idiom containing elements from both languages.[33]

In 1919, after World War I, two neighbouring towns, Královo Pole and Husovice, and 21 other municipalities were annexed to Brno, creating Greater Brno (Czech: Velké Brno). This was done to dilute the German-speaking majority of close to 55,000[34] by the addition of the Slavic communities of the city's neighborhood. Included in the German-speaking group were almost all of the 12,000 Jewish inhabitants, including several of the city's better known personalities, who made a substantial contribution to the city's cultural life.[34] Greater Brno was almost seven times larger, with a population of about 222,000 – before that Brno had about 130,000 inhabitants.[35][36][37]

In 1921 Brno became the capital of the Land of Moravia (Czech: země Moravská); before that it was the capital of the Margraviate of Moravia. Seven years later, Brno became the capital of the Land of Moravia-Silesia (Czech: země Moravskoslezská).

In 1930, 200,000 inhabitants declared themselves to be of Czech, and some 52,000 of German nationality, in both cases including the respective Jewish citizens.[34]

During the German occupation of the Czech lands between 1939 and 1945 all Czech universities including those of Brno were closed by the Nazis. The Faculty of Law became the headquarters of the Gestapo, and the university hall of residence was used as a prison. About 35,000 Czechs and some American and British prisoners of war were imprisoned and tortured there; about 800 civilians were executed or died.[38] Executions were public.[39]

Between 1941 and 1942, transports from Brno deported 10,081 Jews to Theresienstadt (Terezín) concentration camp. At least another 960 people, mostly of mixed race, followed in 1943 and 1944. After Terezín, many of them were sent to Auschwitz concentration camp, Minsk Ghetto, Rejowiec and other ghettos and concentration camps. Although Terezín was not an extermination camp, 995 people transported from Brno died there. After the war only 1,033 people returned.[40]

Industrial facilities such as arms factory Československá zbrojovka and aircraft engine factory Zweigwerk (after the war it became Zbrojovka's subsidiary Zetor) and the city centre were targeted by several Allied bombardment campaigns between 1944 and 1945. The air strikes and later artillery fire killed some 1,200 people and destroyed 1,278 buildings.[41] After the city's occupation by the Red Army on 26 April 1945[42] and the end of the war, ethnic German residents were forcibly expelled. In the so-called Brno death march, beginning on 31 May 1945, about 27,000 German inhabitants of Brno were marched 64 kilometres (40 miles) to the Austrian border. According to testimony collected by German sources, about 5,200 of them died during the march.[43] Later estimates by Czech sources put the death toll at about 1,700, with most deaths due to an epidemic of shigellosis.[44]

At the beginning of the Communist era in Czechoslovakia, in 1948, the government abolished Moravian autonomy and Brno hence ceased to be the capital of Moravia.[45][46] Since then Moravia has been divided into administrative regions and Brno is administrative centre of the South Moravian Region.[45]

In 1960s and 1970s, large panel housing estates were built in border districts (e.g. in Bohunice, Líšeň, Bystr or Vinohrady). During communist era, most workforce was employed in industry (mainly machinery).

After 1989, part of workforce switched from industry to services. Notably, Brno became IT centre of Czechia. Nevertheless, new industrial zones were built at the edge of the city (e.g. Černovická terasa in east).

Geography

Brno is located in the southeastern part of the Czech Republic, at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers and there are also several brooks flowing through it, including the Veverka, Ponávka, and Říčka. The Svratka River flows through the city for about 29 km (18 mi), the Svitava River cuts a 13 km (8 mi) path through the city.[2] Brno is situated at the crossroads of ancient trade routes which have joined northern and southern European civilizations for centuries, and is a part of the Danube basin region. The city is historically connected with Vienna, which lies a mere 110 km (68 mi) to the south.[47]

The width of Brno is 21.5 km (13.4 mi) measured from the east to the west and its overall area is 230 km2 (89 sq mi).[47] Within the city limits are the Brno Reservoir, several ponds, and other standing bodies of water, for example reservoirs in the Marian Valley[48] or the Žebětín Pond. Brno is surrounded by wooded hills on three sides; about 6,379 ha (15,763 acres) of the area of the city is forest, i.e. 28%. Due to its location between the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands and the Southern Moravian lowlands (Dyje-Svratka Vale), Brno has a moderate climate.[2] Compared to other cities in the country, Brno has a very high air quality, which is ensured by a good natural circulation of air; no severe storms or similar natural disasters have ever been recorded in the city.[2]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Brno has an oceanic climate (Cfb) for −3 °C original isoterm,[49] but near of the (−2,5 °C average temperature in January, month most cold) or include by updated classification in humid continental climate (Dfb) with cold winters and warm to hot summers.[50] However, in the last 20 years the temperature has increased, and summer days with temperature above 30 °C (86 °F) are quite common.[51] The average temperature is 9.4 °C (49 °F), the average annual precipitation is about 505 mm (19.88 in), the average number of precipitation days is 150, the average annual sunshine is 1,771 hours, and the prevailing wind direction is northwest.[2] The weather box below shows average data between years 1961 and 1990. Its height above sea level varies from 190 m (623 ft) to 425 m (1,394 ft),[2] and the highest point in the area is the Kopeček Hill.

| Climate data for Brno (Brno–Tuřany Airport), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1939-present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.0 (60.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.8 (100.0) |

32.2 (90.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

37.8 (100.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.1 (34.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

2.0 (35.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.0 (48.2) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

3.5 (38.3) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.3 (24.3) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

14.0 (57.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −24.1 (−11.4) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−18.9 (−2.0) |

−7 (19) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.1 (34.0) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−13 (9) |

−21 (−6) |

−24.1 (−11.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 23.1 (0.91) |

23.4 (0.92) |

29.7 (1.17) |

28.9 (1.14) |

61.2 (2.41) |

72.2 (2.84) |

69.0 (2.72) |

55.7 (2.19) |

47.9 (1.89) |

31.1 (1.22) |

34.0 (1.34) |

31.9 (1.26) |

508.1 (20.00) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 17.4 (6.9) |

12.4 (4.9) |

5.2 (2.0) |

0.6 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

4.5 (1.8) |

12.5 (4.9) |

52.6 (20.7) |

| Average precipitation days | 5.8 | 5.3 | 6.4 | 5.7 | 8.1 | 8.6 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 83.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 84 | 81 | 73 | 65 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 68 | 73 | 78 | 84 | 85 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 53.8 | 82.9 | 137.5 | 208.7 | 226.4 | 246.9 | 245.7 | 246.3 | 175.5 | 112.5 | 59.3 | 44.5 | 1,840 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (UN)[52] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[53] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

Administration

By law Brno is a statutory city; it consists of 29 city districts (administrative divisions, cz: Městské části)[54] the highest body of its self-government is the Assembly of the City of Brno (cz: Zastupitelstvo města Brna).[55] The city is headed by the lord mayor (cz: primátor); he or she has right to use the mayor's insignia and represents the city outwards. As of 2019, the lord mayor is Markéta Vaňková.[56] The executive body is the city council (cz: Rada města Brna) and local councils of the city districts; the city council has 11 members including the lord mayor and her four deputies.[57] The assembly of the city elects the lord mayor and other members of the city council, establishes the local police, and is also entitled to grant citizenship of honour and the Awards of the City of Brno.[55] The head of the Assembly of the City of Brno in personal matters is the Chief Executive (cz: Tajemník magistrátu) who according to certain special regulations carries out the function of employer of the other members of the city management.[58] The Chief Executive is directly responsible to the Lord Mayor.[59]

The city itself forms a separate district the Brno-City District (cz: Okres Brno-město) surrounded by the Brno-Country District (cz: Okres Brno-venkov), Brno is divided into 29 administrative divisions (city districts) and consists of 48 cadastral areas. Confusingly, there is a difference between "a city district of Brno", "the Brno-City District" and "the Brno-Country District".

The city districts of Brno significantly vary in their size by both population and area. The most populated city district of Brno is the Brno-Centre which has over 91 thousand of residents and the less populated are Brno-Ořešín and Brno-Útěchov with about 500 residents. By its area the largest one is Brno-Bystrc with 27.24 square kilometres (10.52 sq mi) and the smallest is Brno-Nový Lískovec with 1.66 square kilometres (0.64 sq mi).

Brno is the home to the highest courts in the Czech judiciary. The Supreme Court is on Burešova Street,[60] the Supreme Administrative Court is on Moravské náměstí (English: Moravian Square),[61] and the Constitutional Court is on Joštova Street,[62] and the Supreme Public Prosecutor's Office of the Czech Republic is on Jezuitská street.[63]

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1869 | 73,771 | — |

| 1880 | 82,660 | +12.0% |

| 1890 | 94,462 | +14.3% |

| 1900 | 109,346 | +15.8% |

| 1910 | 125,737 | +15.0% |

| 1921 | 221,758 | +76.4% |

| 1930 | 264,925 | +19.5% |

| 1950 | 284,946 | +7.6% |

| 1961 | 314,235 | +10.3% |

| 1970 | 344,031 | +9.5% |

| 1980 | 371,463 | +8.0% |

| 1991 | 388,296 | +4.5% |

| 2001 | 376,172 | −3.1% |

| 2011 | 385,913 | +2.6% |

| Source: Růžková, J.; Josef Škrabal, J.; et al. (2006). Historický lexikon obcí České republiky 1869–2005 [Historical lexicon of municipalities in the Czech Republic 1869–2005] (PDF) (in Czech). Díl I. Český statistický úřad. pp. 51–54. ISBN 80-250-1311-1. | ||

According to the 2011 census, Brno had 385,913 inhabitants.[64] The largest ethnic groups were Czechs (51.6%), Moravians (18.7%), Slovaks (1.5%), Ukrainians (0.9%), Vietnamese (0.4%), and Poles (0.2%). But 23.7% of inhabitants did not write any nationality (there were no options for simple ticking). In 2001 census (when the most common nationalities were mentioned to tick), 76.1% were Czechs and 18.7% Moravians, so in total 94.8% Czechs in "wider" meaning.

Brno experienced the largest increase in population during the 19th century at the time of the industrial revolution and in 1919 due to merger with surrounding municipalities.

A slight decrease in population after 1989 was caused by suburbanisation.

Culture

The city spends about 30 million euro every year on culture.[65][66] There are many museums, theatres and other cultural institutions. Brno is also a vibrant university city with about 90,000 students, and a number of festivals and other cultural events.

Since the 1990s Brno has experienced a great cultural "rebirth": façades of historical monuments are being repaired and various exhibitions, shows, etc., are being established or extended. In 2007 a summit of 15 presidents of the EU Member States was held in Brno.[67]

Despite its urban character, some of the city districts still preserve traditional Moravian folklore, including folk festivals with traditional Moravian costumes (cz: kroje), Moravian wines, folk music and dances. Unlike smaller municipalities, in Brno the traditional folk festivals are held locally by city districts: among the city districts where annual traditional Moravian festivals takes place are Židenice,[68] Líšeň,[69] or Ivanovice.[70]

Hantec is a unique slang that originated in Brno.

Sights

Brno has hundreds of historical sights, including one designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO,[71] and eight monuments listed among the national cultural heritage of the Czech Republic.[72][73] Majority of the main sights of Brno are situated in its historical centre. The city has the third largest historic preservation zone in the Czech Republic, the largest one being that of the Czech capital Prague. However, there is a considerable difference in the size of historical preservation zones of both cities. While Brno has 484 legally protected sites, Prague has as many as 1,330.[74]

Špilberk Castle, originally a royal castle founded in the 13th century, was from the 17th century a fortress and feared prison (e.g. Carbonari). Today it is one of the city's principal monuments.[25][75]

Similarly important is the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul. The cathedral was built during the 14th and 15th centuries in place of an 11th-century chapel.[76] In its present form with two neo-Gothic towers it was finished only in 1909. The other large castle near the city is Veveří Castle.[14]

Abbey of Saint Thomas is the place where Gregor Mendel established the new science of genetics. Church of Saint Tomas is the final resting place of its founder Margrave of Moravia John Henry of Luxembourg and his son King of the Romans and Margrave of Moravia Jobst of Moravia. Basilica of the assumption of our Lady the final resting place also of its founder Queen Elisabeth Richeza. Church of Saint James is one of the most preserved and most spectacular Gothic churches in Brno.

Brno Ossuary which is the second largest ossuary in Europe,[77] after the Catacombs of Paris. Another ossuary is Capuchin crypt with mummies of Capuchin monks and some of the notable people of their era, like architect Mořic Grimm or the famous mercenary leader Baron Trenk.[78] The Labyrinth under Vegetable Market, a system of underground corridors and cellars dating back to Middle Ages, has been recently opened to the public.

Brno is home to a functionalist Synagogue and the largest Jewish cemetery in Moravia. A Jewish population lived in Brno as early as the 13th century, and remnants of tombstones can be traced back to as early as 1349.[79] The functionalist synagogue was built between 1934 and 1936.[79] While there were 12,000 members of the Brno Jewish community in 1938, only 1,000 survived the Nazi persecution during Germany's occupation in World War II.[79] Today, the cemetery and synagogue are maintained by a Brno Jewish community once again. The only Czech mosque, founded in 1998, is also located in Brno.[80]

The era between the world wars brought a building boom to the city, leaving it with many modern and especially functionalist buildings,[81][82] the most celebrated one being Villa Tugendhat, designed by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the 1920s for the wealthy family of Fritz Tugendhat, and finished in 1930. It was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2001.[83] Another renowned architect who significantly shaped Brno was Arnošt Wiesner.[84][85][86] Other functionalist buildings include Avion Hotel and Morava Palace. The Brno Exhibition Centre is the city's premier attraction for international business visitors. Annually, over one million visitors attend over 40 professional trade fairs and business conferences held here.

Lužánky is the oldest public park opened in the current Czech Republic, as a public park it was established in the late 18th century.[87] Denis Gardens were founded in the early 19th century and are the first public park in the present-day Czech Republic founded by public administration authorities,[88] while Lužánky Park was founded by the emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Špilberk Park is classified as a national cultural sight of the Czech Republic as a unique piece of garden architecture.[89]

One of Brno's more recent additions is the Brno astronomical clock.

The AZ Tower, opened in 2013 and 111 metres (364 ft) tall, is currently the tallest building in the Czech Republic.

Festivals

The biggest festival held in Brno is the fireworks competition festival Ignis Brunensis (Latin for "Flame of Brno") held annually in June. It is part of a festival with a bold name "Brno - City in the Centre of Europe".[90] Ignis Brunensis is the biggest show of its kind held in Central Europe.[91][92] usually attracts one or two hundred thousand visitors every day.[13]

International film festival Cinema Mundi shows about 60 films competing for Oscar nomination in the category of Best Foreign Language Film.[93]

The Theatre World Brno is another international festival annually held in the city where the Brno theatres and the city centre stages around one hundred performances by both national and foreign ensembles.[94]

There are many other festivals regularly held in Brno, for instance the International Music Festival Brno,[95] the Spilberk International Music Festival,[96] the Summer Shakespeare Festival,[97] and many others...

Every September, Brno is home to a wine festival (Slavnosti vína) to celebrate the harvest in the surrounding wine-producing region.[98]

Theatres

Brno has the oldest theatre building in Central Europe, the Reduta Theatre at Zelný trh (en: the Vegetable Market).[99] So the city has a long tradition in theatre productions, the first theatre plays in Brno took place probably in the 1660s in the City Tavern, today's Reduta Theatre; however, the first "real theatre" with theatre boxes was built in 1733 in this complex.[99] The first documented professional Czech performance took place in 1767 again in the Reduta Theatre, the play was called Zamilovaný ponocný (en: Watchman in Love) and was performed by the Venice Theatre Company; the same year Mozart performed in the theatre with his elder sister Anna Maria (Nannerl).[99] In that year the Mozart family spent Christmas in Brno,[100] this rare visit is commemorated by a statue of Mozart as a child in front of the Reduta Theatre; also the Reduta's Mozart Hall (cz: Mozartův sál) was named after him.[101]

The National Theatre Brno is the leading scene of opera,[103] drama[104] and ballet[105] in the city of Brno. The first permanent seat of the National Theatre Brno was established in 1884 and it was called Národní divadlo v Brně (en: the National Theatre in Brno), today this institution owns the Mahen Theatre, built in 1882, Janáček Theatre built in 1965, and the Reduta Theatre which is Central Europe's oldest theatre.[106] The composer Leoš Janáček is also connected with the National Theatre Brno.[107] Another interesting fact about the National Theatre Brno: the Mahen Theatre was the first theatre building in Europe to be illuminated by Thomas Edison's electric light bulbs; at that time it was a completely new invention and there were no power plants built in the city, so a small steam power plant was built nearby just to power the theatre, and Edison came to Brno in 1911 to see it.[102]

The most commercially successful theatre in Brno is the Brno City Theatre, founded in 1945;[108] its performances are usually sold out. They also stage about 150 performances abroad every year.[109] Repertoire of this theatre consists primarily of musical and dramatical scene.[110]

There is a variety of smaller theatres in Brno, such as Divadlo Bolka Polívky, Divadlo Husa na provázku, HaDivadlo, loutkové divadlo Radost, Divadlo Polárka, G Studio, Divadlo v 7 a půl – Kabinet múz, Divadlo Vaňkovka for children, etc.

The Mahen Theatre was originally called the City Theatre and until 1918 it performed exclusively in German and was not part of the National Theatre in Brno. Between 1971 and 1978 some plays were performed at the Brno Exhibition Centre due to reconstruction of the Mahen Theatre.[111]

Local legends

_v%C3%BD%C5%99ez.jpg)

There are several legends connected with the City of Brno; one of the best known is the Legend of the Brno Dragon.[112] It is said that there was a terrible creature terrorizing the citizens of Brno. The people had never seen such a beast before, so they called it a dragon. They trembled in fear of the dragon until a brave man decided to kill the monster by tricking it into eating a carcass filled with lime. In reality the dragon was a crocodile, the preserved body of which is now displayed at the entrance of the Old Town Hall. Crocodile and dragon motifs are common in Brno. A "krokodýl" (crocodile in Czech language) is the local stuffed baguette, and the city radio station is known as Radio Krokodýl. Local baseball team is named Draci Brno (en: Dragons Brno) and local rugby club is named RC Dragon Brno, there is also local American football team called Brno Alligators. Intercity train connecting Brno and Czech capital city Prague is called Brněnský drak (en: Brno dragon).

Next to the "dragon" at the Old Town Hall the town's second well-known emblem is displayed. This is a wagon wheel made from a tree found and felled fifty miles away from the city. According to the story, a local man wagered to fell the tree, to make a wheel out of it, and to roll the wheel to the city of Brno, all this within a single day. Since the whole achievement was considered impossible by normal human means, the man was later believed to have called on the devil for assistance, and he died in poverty as a result.[113]

As a historic memento to victory over the Swedish army in 1645, the local Petrov Cathedral rings noon an hour earlier, at 11 o'clock because the locals and Swedish army were in stalemate and the Swedish general said he would withdraw if his army had not won by noon; the bell ringer tricked him by ringing the bell an hour early. Keeping his word, the general and his army left.[114]

Museums, libraries, and galleries

The most significant museum in Brno is the Moravian Museum which is the largest and the biggest museum in Moravia and the second in the Czech Republic.[115] The museum was founded in 1817 and its collections include over 6 million objects.[115] The biggest public library in Brno is the Moravian Library, it is the second largest library in the Czech Republic with about 4 million volumes.[116] The biggest gallery in Brno is the Moravian Gallery and again it is the second largest institution of its kind in the Czech Republic and the biggest in Moravia.[117] There is also a particular section of the Moravian Museum related to the oldest history of mankind and prehistoric Europe called Anthropos.

There is also a Technical Museum which is the largest in Moravia and one of the largest in Czech Republic. The permanent expositions of the Technical Museum in Brno show the advance of science and technology, accompanied by various realistic models and restored machines. Short-term exhibitions of many different points of interest are also often held here.[118]

Education

.jpg)

Over the past two decades Brno evolved into an important university city, the number of students of higher education institutions reached 89,000 in 2010.[8] The city also became home to a number of institutions directly related to research and development, like the Central European Institute of Technology (CEITEC),[119] or the International Clinical Research Center in Brno (ICRC).[120] The city is also gaining importance in various fields of engineering, especially in software development, there are a number of companies focused on development operating in Brno. For example, AVG Technologies (headquarters),[121] IBM (Client Innovation Centre Brno),[122] AT&T (American Telephone and Telegraph) Honeywell (Honeywell Global Design Center Brno),[123] Siemens,[124] SGI (CZ headquarters),[125] Red Hat (CZ headquarters),[126] Motorola,[127] etc.

With over 40,000 students, Masaryk University is the largest university in Brno and the second biggest in the Czech Republic.[128] Today, it consists of nine faculties, with more than 190 departments, institutes and clinics. It is one of the most significant institutions for education and research in the Czech Republic and a respected Central European university.[129]

The Brno University of Technology was established in 1899. Today with over 20,000 students it ranks among the Czech's biggest technical universities. Viktor Kaplan, inventor of the Kaplan turbine, spent nearly 30 years at German Technical University in Brno (which ceased to exist in 1945 and its property was transferred to Brno University of Technology).

Mendel University, named after the founder of genetics Gregor Mendel who created his revolutionary scientific theories in Brno, has roughly 10,000 students.

Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts, named after Leoš Janáček, was founded in 1947 and is one of two academies of music and drama in the Czech Republic.[130] It holds the annual Leoš Janáček Competition.[131]

Sports

The city has a long history of motor racing; among other events, the Masaryk Circuit hosts the prestigious Moto GP championship (since 1965). The annual Czech Republic motorcycle Grand Prix is the most famous motor race in the Czech Republic, it is held here since 1950. Since 1968, Brno has been a permanent fixture on the European Touring Car Championship (ETCC) series.

2010 FIBA World Championship for Women, where Czech squad managed to achieve silver medal, was played in Brno's Arena Vodova.

There is also a horse-race course at Brno-Dvorská and an aeroclub airport in Medlánky. Several sports clubs represent the city in the various Czech leagues, including (football) FC Zbrojovka Brno, (ice hockey) HC Kometa Brno, (handball) KP Brno, (basketball) BC Brno (men) and BK Brno (women), four baseball teams (Draci Brno, Hroši Brno, VSK Technika Brno, MZLU Express Brno), lacrosse team Brno Ravens Lacrosse Club, American football team (Brno Alligators), two rugby teams (RC Dragon Brno, RC Bystrc) and others. Tennis player Lucie Šafářová comes from Brno as well as Lukáš Rosol, who managed to beat top-player Rafael Nadal in the second round of the 2012 Wimbledon Championships. Michal Březina, one of the best Czech figure skaters, also comes from Brno.

Transport

Public transport in Brno consists of 12 tram lines (1 historic with old trams), 14 trolleybus lines (the largest trolleybus network in the Czech Republic) and almost 40-day and 11 night bus lines.[133] Trams (often called šaliny by the locals[134]) have a long tradition in Brno; they first appeared on the streets in 1869; this was the first operation of horse-drawn trams in the current Czech Republic.[32] The local public transport system is interconnected with regional public transport in one integrated system called IDS JMK, and also directly connects several nearby municipalities with the city.[135] Its main operator is the DPmB company (Brno City Transport Company) which also operates a ferry route, mainly recreational, at the Brno Dam Lake.[136] There is a tourist minibus providing a brief tour of the city.[137] In 2011, the city announced plans to build a metro system light rail system to alleviate overcrowding of trams and to reduce the congestion on the surface.[138][139][140]

Railway transport started to operate in the city in 1839 on the Brno–Vienna line; this was the first operating railway line in the current Czech Republic.[31] Today's Brno is a railway junction of supranational importance; for passenger traffic there are nine stations and stops. The current main railway station is the central hub of regional train services; every day about 50,000 passengers use it and 500 trains pass through it; it is currently operating at full capacity.[141] The current main station building is outdated and lacks sufficient operating capacity, but the construction of the new station has been postponed several times for various reasons.[141] A Central station referendum was held on 7 and 8 October 2016, the same day as regional elections.

Road transport makes Brno an international crossroad of highways. There are two motorways on the southern edge of the city, D1 leading to Ostrava and to Prague and D2 leading to Bratislava.[142] Not far from the city limits there is also one expressway, R52, leading to Vienna; another expressway, R43, which will connect Brno to northwestern Moravia, is planned.[142] The city is gradually building the large city ring road (road I/42), several road tunnels were built (Tunnels Pisarky, Husovice, Hlinky and Královopolský) and more tunnels are planned.[143] Also, due to the congestion in private transport the city continues to strive to build more parking ramps including underground ones, but this effort has not always been successful.[144]

Air transport is enabled by two functional airports. One of them is a public international airport Brno-Tuřany Airport. The airport has seen a sharp increase in passenger traffic up to 2011, however the amount of served passengers has been since in decline with the only remaining scheduled flights being to London and Munich. The airport also serves as one of the two bases for police helicopters in the Czech Republic. The other airport, Medlánky Airport, is a small domestic airport serving mainly recreational activities such as flying hot air balloons, gliders or aircraft RC models.[145][146][147]

Cycling is widespread in Brno also due to lowland nature of the landscape. Existing tracks for cycling and roller skating in 2011 measured in total approximately 38 kilometres (24 mi) and are gradually being expanded.[148] And there is also one long bikeway leading to Vienna, the track is approximately 130 kilometres (81 mi) long.[149] Several hiking trails of the Czech Tourist Club also pass through Brno.

Notable people

- Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), scientist, friar

- Maria Neruda (1840–1920), violinist

- Ladislav Vácha (1899–1943), gymnast

- Jan Gajdoš (1903–1945), gymnast

- Rudolf Potsch (born 1937), ice hockey player

- Rudolf Adler (born 1941), Czech filmmaker

- Peter G. Hartman (born 1947), biochemist

- Jiří Pospíšil (1950–2019), basketball player

- Miroslav Knapek (born 1955), rower

- Jan Stejskal (born 1962), footballer

- Roman Kukleta (1964–2011), football player

- Robert Kron (born 1967), ice hockey player

- Jana Novotná (1968–2017), tennis player

- Jaromír Blažek (born 1972), footballer

- Libor Zábranský (born 1973), ice hockey player and coach

- David Kostelecký (born 1975), sports shooter

- Kamil Brabenec (born 1976), ice hockey player

- Robert Kántor (born 1977), ice hockey player

- Marek Vorel (born 1977), ice hockey player

- Adam Svoboda (1978–2019), ice hockey player

- Petr Hubáček (born 1979), ice hockey player

- Miroslava Knapková (born 1980), rower

- Jan Polák (born 1981), footballer

- Lucie Šafářová (born 1987), tennis player

- Karel Abraham (born 1990), motorcycle racer

- Nicole Melichar (born 1993), tennis player

- Adam Ondra (born 1993), rock climber

- Libor Zábranský (born 2000), ice hockey player

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Cooperation agreements

Nearby cities

This tool shows only cities with population over 300,000 in radius of 300 km (186.41 mi).

Gallery

- A view from the Špilberk castle

- Petrov cathedral

The Liberty Square, in the Middle Ages it was the main square

The Liberty Square, in the Middle Ages it was the main square The Bishop's Palace towards the Cathedral

The Bishop's Palace towards the Cathedral Tivoli

Tivoli.jpg)

Hotel Grand

Hotel Grand Brno astronomical clock

Brno astronomical clock Masarykova Street

Masarykova Street.jpg) Líšeň Castle

Líšeň Castle New Town Hall

New Town Hall Moravian Gallery - Pražák Palace

Moravian Gallery - Pražák Palace Denis Gardens with obelisk

Denis Gardens with obelisk Špilberk castle

Špilberk castle Functionalist Agudas Achim Synagogue by Otto Eisler

Functionalist Agudas Achim Synagogue by Otto Eisler Central Bus Station Brno

Central Bus Station Brno

See also

- List of people from Brno

- Churches of Brno

- National Theatre (Brno)

Notes

- This led to decline in population of Olomouc from over 30,000 people to mere 1,675 and total devastation of the city.

- However, Olomouc also had legal status of capital city, although this title was purely a honorary matter rather than a real role, sometimes it was referred to as "the Secondary Capital".

- The cathedral of the bishopric of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brno, the Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul, is depicted on the 10CZK coin.

References

- "History of the City of Brno". The Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Where in the world is Brno? – Statutory city of Brno" (in Czech). The Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Population of Municipalities – 1 January 2020". Czech Statistical Office. 30 April 2020. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Brno". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- "Vymezení funkčního území Brněnské metropolitní oblasti a Jihlavské sídelní aglomerace" (PDF) (in Czech). Statutární město Brno. 2013. p. 60–63. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "The Public Defender of Rights". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Office for the Protection of Competition". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Brno v číslech" [Brno in Numbers] (PDF) (in Czech). The Statutory City of Brno. 2010: 85. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Informace o společnosti – Veletrhy Brno" (in Czech). Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "Basic Info – BVV Trade Fairs Brno". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "1930 – 1986 Automotodrom Brno". Archived from the original on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "ABOUT THE FESTIVAL". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Celková návštěvnost festivalových akcí" (in Czech). Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- "Weekend trip tip: hike to Veveří castle, take a ferry boat back to Brno". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Veverské pověsti a legendy" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Old Town Hall of Brno – Brno Tourist Informations". Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Introduction – Vila Tugendhat". Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Brno | Creative Cities Network". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- E.M. Pospelov, Geograficheskie nazvaniya mira (Moscow, 1998), p. 82.

- "What does Brunn mean?". AudioEnglish.org. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "WordNet Search". WordNet. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "History of the City of Brno". the Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Naučná stezka Hády a údolí Říčky. Panel 14: Staré Zámky" (PDF) (in Czech). ZO ČSOP Pozemkový spolek Hády. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- Čapka, František (2003). "Ota Olomoucký a Konrád Brněnský". Morava. Stručná historie států (in Czech). Praha: Libri. p. 30. ISBN 80-7277-186-8.

- "Spilberk Castle – Špilberk, Brno Castle, the home of Brno City Museum". Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- "Opatství svatého Tomáše na Starém Brně". Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- Garstein, Oskar (1992). Rome and the Counter-Reformation in Scandinavia: The age of Gustavus Adolphus and Queen Christina of Sweden, 1622–1656. BRILL.

- "Moravské desky zemské" (in Czech). Ministerstvo vnitra České republiky. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- "Brno – Historie v datech" (in Czech). Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Napoleon I. in Moravia's capital in 1809, Brno, Czech Republic - La Famille Bonaparte on Waymarking.com". Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "První parní vlak do dnešního Česka přijel z Vídně do Brna – Doprava – ČT24 – Česká televize" (in Czech). ČT. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Dopravní podnik města Brna, a.s. Historie" (in Czech). DPmB. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Die Stadt Brünn – offizielle Webseiten der BRUNA über die Stadt Brünn". www.bruenn.eu.

- Eva Hahn, Hans Henning Hahn: Die Vertreibung im deutschen Erinnern. Legenden, Mythos, Geschichte. Schöningh, Paderborn 2010, ISBN 978-3-506-77044-8, p. 370.

- "Výstava Velké Brno" (in Czech). Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Statistické údaje za Zemi Moravskoslezskou k roku 1930" (PDF) (in Czech). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Zákon č. 213/1919 Sb., o sloučení sousedních obcí s Brnem" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- JUDr. František Vašek. "Kounicovi koleje v Brně". zasvobodu.cz (in Czech). Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Leoš Drahota: Naše šibenice 16 – Novodobé věšení, ISSN 1213-6905 "Exekuce v Kounicových kolejích byly veřejné, ale vstup byl možný, podobně jako v případě nějaké kulturní či sportovní akce, jen s platnou vstupenkou, prodávanou za tři marky."

- Klementová, Táňa (2010). "Poslední nástupiště Brněnské transporty židů v letech 1941–1945" (PDF). Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Vlček, Martin (24 May 2008). "Spojenecké nálety na Brno v letech 1944–1945". Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "Encyklopedie dějin města Brna". encyklopedie.brna.cz. 2 May 2019.

- Bundesministerium für Vertriebene, Flüchtlinge und Kriegsgeschädigte & Theodor Schieder eds.: Die Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa. Vorarbeiten Fritz Valjavec. Teil 4: Die Vertreibung der deutschen Bevölkerung aus der Tschechoslowakei. Bonn, 1957, 2 Bände.

- Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana (2019). Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742510944.

- "Zákon 208/1948 Sb. o krajském zřízení" (PDF) (in Czech). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "280/1948 Sb. Zákon o krajském zřízení" (in Czech). Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Geografické údaje a obyvatelstvo – Statutární město Brno" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "South Moravia – Official Tourism Website". Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "Brno, Czech Republic Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 February 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "World Weather Information Service – Brno". World Meteorological Organization. May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Brno Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- "Basic data on city districts offices". The Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Assembly of the City of Brno". The Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Primátorka města Brna". Brno.cz. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Executive Board, Brno City Council". The Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 21 October 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Elected bodies". The Statutory city of Brno. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Tajemník Magistrátu města Brna" (in Czech). The Statutory city of Brno. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "The Supreme Court of the Czech Republic". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "The Supreme Administrative Court". Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "The Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic". Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "Nejvyšší státní zastupitelství – Introduction". Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- "Základní výsledky". Český statistický úřad. 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- "Schválený rozpočet provozních a kapitálových výdajů – Rekapitulace dle oddílů a paragrafů" (in Czech). Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Souhrnný rozpočet statutárního města Brna na rok 2010 – Rozpočet výdajů statutárního města Brna" (in Czech). Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- "Reference – Moravia Convention Bureau" (in Czech). Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Židenické hody – Brno Židenice – www.kalendarakci.atlasceska.cz" (in Czech). Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Líšeňské hody – portál vlisni.cz" (in Czech). Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "ČÍ JSOU HODY? NAŠE! » Městská část Brno Ivanovice" (in Czech). Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Tugendhat Villa in Brno – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Světové dědictví, NKP, chráněná území – okres Brno-město" (in Czech). The National Institute for the Protection and Conservation of Monuments and Sites of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Kulturní památky" (in Czech). The Ministry of the interior of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Národní památkový ústav: Světové dědictví, NKP, chráněná území" (in Czech). The National Institute for the Protection and Conservation of Monuments and Sites of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Spilberk Castle – history". Spilberk.cz. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- Statutory city of Brno. "City of Brno – Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul". Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Brno Ossuary located in Brno, Czech Republic". Atlas Obscura – Curious and Wondrous Travel Destinations. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Capuchin Crypt". The Capuchin Monastery in Brno. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "The History of the Jewish Community in Brno" (in Czech). 27 September 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Mešita Brno" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "Brno – Funkcionalismus a moderní architektura" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Tvorba architekta funkcionalismu Fuchse přinesla novou estetiku – iDNES.cz" (in Czech). Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- Statutory city of Brno. "City of Brno – Villa Tugendhat". Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Tourist Portal of the Czech Republic – Interwar architecture in Brno". Czecot.com. 15 February 2006. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- Karrie Jacobs, Discovering Brno's architecture, in Travel + Leisure, November 2005, available online

- webProgress.cz. "The Chamber of Tax Advisers of the Czech Republic – Some information about Brno". Kdpcr.cz. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Park Lužánky – Statutární město Brno" (in Czech). Statutory City of Brno. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "park Denisovy sady – Přehled kulturních památek – Statutární město Brno" (in Czech). Statutory City of Brno. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Park Špilberk – Statutární město Brno" (in Czech). Statutory City of Brno. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "About the festival". Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "Brno chystá velkolepé ohňostroje, festival by mohl vidět milion diváků" (in Czech). Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Brno – Concentus Moraviae" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "About the festival / About the festival / Cinema Mundi returns to Brno after one year - www.cinemamundi.info". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Festival – DIVADELNÍ SVĚT BRNO". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Moravian autumn – Introduction". Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Spilberk Festival – Brno Philharmonic Orchestra". Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Welcome to Summer Shakespeare Festival 2011, Summer Shakespeare Festival 2011, AGENTURA SCHOK, spol. s r.o., Praha". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Slavnostivina". slavnostivina.cz. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Historie divadla Reduta, Národní divadlo Brno" (in Czech). The National Theatre Brno. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Brno – Mozart v Brně" (in Czech). The Statutory City of Brno. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Divadlo Reduta, Mozartův sál, Národní divadlo Brno" (in Czech). The National Theatre Brno. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Historie Mahenova divadla, Národní divadlo Brno" (in Czech). The National Theatre Brno. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Opera, Národní divadlo Brno". The National Theatre Brno. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Drama, Národní divadlo Brno". The National Theatre Brno. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Ballet, Národní divadlo Brno". The National Theatre Brno. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Buildings, Národní divadlo Brno" (in Czech). The National Theatre Brno. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Leoš Janáček a Národní divadlo v Brně 1884–1928, Národní divadlo Brno" (in Czech). The National Theatre Brno. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Městské divadlo Brno – Theatre / History". The Brno City Theatre. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Městské divadlo Brno – Theatre / Today". The Brno City Theatre. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Městské divadlo Brno – Performances". The Brno City Theatre. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Fenomén Městského divadla v Brno v brněnské kultuře" (PDF) (in Czech). Masarykova univerzita, Filozofická fakulta, Ústav hudební vědy. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- "Old Town Hall of Brno – Brno Tourist Informations". Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Henig 2000, p. 93.

- "The Moravian Museum". Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "About the Library". The Moravian Library in Brno. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "The Moravian Gallery in Brno – History". Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- s.r.o, Pixelfield. "The Art of Enamelling / The Enamelling Technique".

- "CEITEC". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "FNUSA ICRC". Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- "AVG Antivirus and Security Software – Contact us". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "IBM Governmental Programs – Delivery Centre Central Eastern Europe in Brno". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "Honeywell Global Design Center Brno – Honeywell Czech Republic". Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "Brno – – Siemens" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "SGI – Global – Česká Republika" (in Czech). Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "Red Hat Europe". Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "MOTOROLA – Technology Park Brno". Archived from the original on 29 May 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "Marasyk University, Brno". Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- "Brief history of the Masaryk University". Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- "Janáček Academy – history". Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Janáček Academy – Leoš Janáček Competition". Hf.jamu.cz. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- "Portál Jihomoravského kraje – Základní údaje o Jihomoravském kraji – Základní údaje o Jihomoravském kraji" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Timetable of IDS JMK". Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Dražní vozidla – Fotoalbum – Tramvaje – Šaliny – Brno KT8D5 na Stranské Skale". www.draznivozidla.estranky.cz.

- "IDS JMK – Integrated public transport system in the City of Brno and the Southern Moravia Region". Archived from the original on 29 July 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Dopravní podnik města Brna, a.s." Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "BKC – kina Art a Scala". Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Brněnské "metro" už je na stole úředníků kraje, peníze na ně nejsou – iDNES.cz" (in Czech). Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Na brněnské "metro" chybí už jen peníze" (in Czech). vz24.cz. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Studie: Metro v Brně bude v roce 2030 – Brněnský deník" (in Czech). Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Hlavní nádraží v Brně není nafukovací, některé vlaky proto končí v Židenicích" (in Czech). iDNES.cz. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- Roads and Motorways in the Czech Republic 2009 (PDF). The Czech Road and Motorway Directorate. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2011.

- "Velký městský okruh Brno (VMO Brno) – Úseky VMO Brno" (in Czech). Ředitelsví silnic a dálnic ČR. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "S firmou, která měla stavět parkovací domy, Brno neprodlouží smlouvu" (in Czech). iDNES.cz. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Aeroklub Brno Medlánky" (in Czech). Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Stránky medláneckých leteckých modelářů" (in Czech). Archived from the original on 25 December 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Zajímavosti: Circa urbem Brunensis 2. – Netopýrky za Komínem" (in Czech). MAGAZÍN LETIŠTĚ ČESKÉ REPUBLIKY. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- "Brno na kole » Změny města v roce 2010" (in Czech). Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "O nás – Cyklostezka Brno Vídeň" (in Czech). Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Partnerská města". brno.cz (in Czech). Brno. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Portugalsko: Obchodní a ekonomická spolupráce s ČR (4.5. Smluvní základna mezi oběma státy)" (in Czech). 1 March 2004.

Bibliography

- Henig, Robin Marantz (2000). The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, the Father of Genetics. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0395-97765-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Filip, Aleš (2006). Brno - city guide. Brno: K-Public. ISBN 80-87028-00-7

- Gödel, Alois (2006). " Brünn 1679-1684" , Brno: ITEM. ISBN 80-902297-8-6

- Procházka, Jiří.(2008)." 1683. Vienna obsessa. Brunna" Brno ITEM. ISBN 80-903476-6-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brno. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brünn. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Brno. |

- Official city website

- Official tourism website

- Living in Brno – English News for foreigners. Linked to many international social groups in the city.

- Brno Now – latest news for expats working, studying or doing business in Brno, Czech Republic

- Tourist Information Center Brno

- Public Transport in Brno