Euparkeria

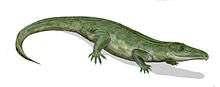

Euparkeria (/juːˌpɑːrkəˈriːə/; meaning "Parker's good animal", named in honor of W.K. Parker) is an extinct genus of archosauriform from the Middle Triassic of South Africa. It was a small reptile that lived between 245-230 million years ago, and was close to the ancestry of Archosauria, the group that includes dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and modern birds and crocodilians.

| Euparkeria | |

|---|---|

| |

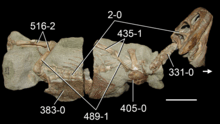

| SAM-PK-5867, the holotype skeleton of Euparkeria capensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Family: | †Euparkeriidae |

| Genus: | †Euparkeria Broom, 1913 |

| Type species | |

| †Euparkeria capensis Broom, 1913 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Euparkeria had hind limbs that were slightly longer than its forelimbs, which has been taken as evidence that it may have been able to rear up on its hind legs as a facultative biped. Although Euparkeria is close to the ancestry of fully bipedal archosaurs such as early dinosaurs, it probably developed bipedalism independently. Euparkeria was not as well adapted to bipedal locomotion as dinosaurs and its normal movement was probably more analogous to a crocodilian high walk.

Palaeobiology

Locomotion

The hind limbs of Euparkeria are somewhat longer than its forelimbs, which has led many researchers to conclude that it could have occasionally walked on its hind legs as a facultative biped. Other possible adaptations to bipedalism in Euparkeria include rows of osteoderms that could have stabilized the back and a long tail that could act as a counterbalance to the rest of the body. Paleontologist Rosalie Ewer suggested in 1965 that Euparkeria may have spent most of its time on four legs but moved on its hind legs while running. However, adaptations to bipedalism in Euparkeria are not as obvious as they are in some other Triassic archosauriforms such as dinosaurs and poposauroids; the forelimbs are still relatively long and the head is so large that the tail may not have effectively counterbalanced its weight. The position of muscle anchorage points on the humerus or thigh bones suggest that Euparkeria could not have held its legs in a fully erect posture beneath its body, but would have held them slightly out to the side as in modern crocodilians and most other quadrupedal Triassic archosauriforms. Euparkeria has a large backward-pointing projection on the calcaneum (an ankle bone) that would have given strong leverage to the ankle during locomotion. A calcaneal projection may have enabled Euparkeria to move with all four limbs in a semi-erect "high walk" similar to the way in which living crocodilians sometimes move about on land.[1]

Nocturnality

Some specimens of Euparkeria preserve bony rings in the eye sockets called sclerotic rings, which in life would have supported the eye. The sclerotic ring of Euparkeria is most similar to those of modern birds and reptiles that are nocturnal, suggesting that Euparkeria may have had a lifestyle adapted to low light conditions. During the Early Triassic the Karoo Basin was at about 65 degrees south latitude, meaning that Euparkeria would have experienced long periods of darkness in winter months.[2]

Classification

The family Euparkeriidae is named after Euparkeria. The family name was first proposed by German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene in 1920; Huene classified euparkeriids as members of Pseudosuchia, a traditional name for crocodilian relatives from the Triassic (Pseudosuchia means "false crocodiles"). Early phylogenetic analyses created by Jacques Gauthier in the 1980s provided an alternative hypothesis, that Euparkeria was closer to dinosaurs (including birds) rather than crocodilians.[3]Many genera have been assigned to Euparkeriidae in the past, but only two other valid genera are currently believed to be part of the family, apart from Euparkeria itself: Halazhaisuchus and Osmolskina.[4]

More recent analyses starting with Benton & Clark (1988)[5] place Euparkeria as a member of Archosauriformes in a position outside both crocodilian-line and bird-line (Avemetatarsalian). Although the ancestor to archosaurs likely shared several similarities with Euparkeria, archosaurs are probably not directly descendants of the genus. The precise placement of Euparkeria and other euparkeriids within Archosauriformes is controversial.

Most analyses agree that Euparkeria was a closer relative of archosaurs than the proterosuchids or erythrosuchids were. The one exception is the study of Dilkes & Sues (2009), who found Euparkeria to be less crownward than Erythrosuchus.[6] Nevertheless, these results have not been widely accepted.[7] There still remains some ambiguity over whether Euparkeriidae was truly the sister group of the archosaurs. Many phylogenetic analyses place the long-snouted proterochampsians as more closely related to archosaurs than euparkeriids were. Such studies include Sereno (1991)[8], Parrish (1993)[9], Juul (1994)[10], various analyses by Michael J. Benton[11], and Ezcurra (2016).[12]

On the other hand, several other notable studies consider Euparkeria to be closer to archosaurs than proterochampsians. Sterling Nesbitt's influential 2011 monograph on archosaurian relationships found a similar result, although he also placed phytosaurs as the sister group to Archosauria, rather than Euparkeria.[13] Roland Sookias, a paleontologist responsible for many studies on euparkeriids in the 2010s, also considers them to be closer archosaur relatives than the proterochampsians.[1][4] Like Nesbitt (2011), he found phytosaurs to be the closest relatives of Archosauria, followed by the Euparkeria-like reptile Dorosuchus, and then by the euparkeriids.[7]

References

- Sookias, R. B.; Butler, R. J. (2013). "Euparkeriidae". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 379: 35–48. doi:10.1144/SP379.6.

- Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science. 332 (6030): 705–8. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820.

- Gauthier, Jacques (1986). "Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds". In Padian, Kevin (ed.). The Origin of Birds and the Evolution of Flight. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences. pp. 1–55. ISBN 978-0-940228-14-6.

- Sookias, Roland B.; Sullivan, Corwin; Liu, Jun; Butler, Richard J. (2014-11-25). "Systematics of putative euparkeriids (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) from the Triassic of China". PeerJ. 2: e658. doi:10.7717/peerj.658. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4250070. PMID 25469319.

- Benton, Michael J.; Clark, James M. (1988). "Archosaur phylogeny and the relationships of the Crocodylia" (PDF). In Benton, Michael J. (ed.). Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 295–338. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2007.

- Dilkes, D.; Sues, H. D. (2009). "Redescription and phylogenetic relationships of Doswellia kaltenbachi (Diapsida: Archosauriformes) from the Upper Triassic of Virginia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29: 58–79. doi:10.1080/02724634.2009.10010362.

- Sookias, Roland B. (2016-03-01). "The relationships of the Euparkeriidae and the rise of Archosauria". Open Science. 3 (3): 150674. doi:10.1098/rsos.150674. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 4821269. PMID 27069658.

- Sereno, Paul C. (1991). "Basal Archosaurs: Phylogenetic Relationships and Functional Implications". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 sup 004: 1–53. doi:10.1080/02724634.1991.10011426.

- Parrish, J. Michael (1993). "Phylogeny of the Crocodylotarsi, with reference to archosaurian and crurotarsan monophyly". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 13 (3): 287–308. doi:10.1080/02724634.1993.10011511. JSTOR 4523513.

- Juul, Lars (1994). "The phylogeny of basal archosaurs" (PDF). Palaeontologia Africana. 31: 1–38.

- Benton, M. J. (1999-08-29). "Scleromochlus taylori and the origin of dinosaurs and pterosaurs". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 354 (1388): 1423–1446. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0489. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1692658.

- Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- Nesbitt, S.J. (2011). "The Early Evolution of Archosaurs: Relationships and the Origin of Major Clades" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 352: 189. doi:10.1206/352.1. ISSN 0003-0090.