Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island (Norwegian: Bouvetøya[2] or Bouvet-øya,[1] Urban East Norwegian: [bʊˈvèːœʏɑ])[2][1][3] is an uninhabited subantarctic high island and dependency of Norway located in the South Atlantic Ocean at 54°25′S 3°22′E, thus locating it north of and outside the Antarctic Treaty System. It lies at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and is the most remote island in the world, approximately 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) north of the Princess Astrid Coast of Queen Maud Land, Antarctica, 1,900 kilometres (1,200 mi) east of the South Sandwich Islands, 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) south of Gough Island, and 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) south-southwest of the coast of South Africa.

Bouvet Island | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) Location of Bouvet Island (circled in red, in the Atlantic Ocean) | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Annexed by Norway | 23 January 1928 |

| Dependency status | 27 February 1930[1] |

| Nature reserve declared | 17 December 1971[2] |

| Government | Dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Harald V |

• Administered by | Ministry of Justice and Public Security |

| Area | |

• Total | 49 km2 (19 sq mi) |

| 93% | |

| Highest elevation | 780 m (2,560 ft) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 0 |

| ISO 3166 code | BV |

| Internet TLD | |

IUCN category Ia (strict nature reserve) | |

The island has an area of 49 square kilometres (19 sq mi), of which 93 percent is covered by a glacier. The centre of the island is an ice-filled crater of an inactive volcano. Some skerries and one smaller island, Larsøya, lie along the coast. Nyrøysa, created by a rock slide in the late 1950s, is the only easy place to land and is the location of a weather station.

The island was first spotted on 1 January 1739 by Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier, on a French exploration mission in the South Atlantic with the ships Aigle and Marie. They did not make a landfall, and he mislabeled the coordinates for the island and the island was not sighted again until 1808, when the British whaler captain James Lindsay named it Lindsay Island.[4] The first claim of landing, although disputed, was by American sailor Benjamin Morrell. In 1825, the island was claimed for the British Crown by George Norris, who named it Liverpool Island. He also reported Thompson Island as nearby, although this was later shown to be a phantom island. The first Norvegia expedition landed on the island in 1927 and claimed it for Norway. At this time the island was named Bouvet Island, or "Bouvetøya" in Norwegian.[5] After a dispute with the United Kingdom, it was declared a Norwegian dependency in 1930. It became a nature reserve in 1971.

History

Discovery and early sightings

The island was discovered on 1 January 1739 by Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier, commander of the French ships Aigle and Marie.[6] Bouvet, who was searching for a presumed large southern continent, spotted the island through the fog and named the cape he saw Cap de la Circoncision. He was not able to land and did not circumnavigate his discovery, thus not clarifying if it was an island or part of a continent.[7] His plotting of its position was inaccurate,[8] leading several expeditions to fail to find the island again.[9] James Cook's second voyage set off from Cape Verde on 22 November 1772 to find Cape Circoncision, but was unable to find the cape.[10]

The next expedition to spot the island was in 1808 by James Lindsay, captain of the Samuel Enderby & Sons' (SE&S) snow whaler Swan.[11] Swan and another Enderby whaler, Otter were in company when they reached the island and recorded its position, though they were unable to land.[12][13] Lindsay could confirm that the "cape" was indeed an island.[7] The next expedition to arrive at the island was American Benjamin Morrell and his seal hunting ship Wasp. Morrell, by his own account, found the island without difficulty (with "improbable ease", in the words of historian William Mills)[12] before landing and hunting 196 seals.[7] In his subsequent lengthy description, Morrell does not mention the island's most obvious physical feature, its permanent ice cover.[14] This has caused some commentators to doubt whether he actually visited the island.[12][15]

On 10 December 1825, SE&S's George Norris, master of the Sprightly, landed on the island,[7] named it Liverpool Island and claimed it for the British Crown and George IV on 16 December.[16] The next expedition to spot the island was Joseph Fuller and his ship Francis Allyn in 1893, but he was not able to land on the island. German Carl Chun's Valdivia Expedition arrived at the island in 1898. They were not able to land, but dredged the seabed for geological samples.[17] They were also the first to accurately fix the island's position.[16] At least three sealing vessels visited the island between 1822 and 1895. A voyage of exploration in 1927-28 also took seal pelts.[18]

Norris also spotted a second island in 1825, which he named Thompson Island, which he placed 72 kilometres (45 mi) north-northeast of Liverpool Island. Thompson Island was also reported in 1893 by Fuller, but in 1898 Chun did not report seeing such an island, nor has anyone since.[17] However, Thompson Island continued to appear on maps as late as 1943.[19] A 1967 paper suggested that the island might have disappeared in an undetected volcanic eruption, but in 1997 it was discovered that the ocean is more than 2,400 metres (7,900 ft) deep in the area.[20]

Norwegian annexation

In 1927, the First Norvegia Expedition, led by Harald Horntvedt and financed by Lars Christensen, was the first to make an extended stay on the island. Observations and surveying were conducted on the islands and oceanographic measurements performed in the sea around it. At Ny Sandefjord, a small hut was erected and, on 1 December, the Norwegian flag was hoisted and the island claimed for Norway. The annexation was established by a royal decree on 23 January 1928.[16] The claim was initially protested by the United Kingdom, on the basis of Norris's landing and annexation. However, the British position was weakened by Norris's sighting of two islands and the uncertainty as to whether he had been on Thompson or Liverpool (i.e. Bouvet) Island. Norris's positioning deviating from the correct location combined with the island's small size and lack of a natural harbour made the UK accept the Norwegian claim.[21] This resulted in diplomatic negotiations between the two countries, and in November 1929, Britain renounced its claim to the island.[16]

The Second Norvegia Expedition arrived in 1928 with the intent of establishing a manned meteorological radio station, but a suitable location could not be found.[16] By then both the flagpole and hut from the previous year had been washed away. The Third Norvegia Expedition, led by Hjalmar Riiser-Larsen, arrived the following year and built a new hut at Kapp Circoncision and on Larsøya. The expedition carried out aerial photography of the island and was the first Antarctic expedition to use aircraft.[22] The Dependency Act, passed by the Parliament of Norway on 27 February 1930, established Bouvet Island as a dependency, along with Peter I Island and Queen Maud Land.[1] The eared seal was protected on and around the island in 1929 and in 1935 all seals around the island were protected.[23]

Recent history

In 1955, the South African frigate Transvaal visited the island.[24] Nyrøysa, a rock-strewn ice-free area, the largest such on Bouvet, was created sometime between 1955 and 1958, probably by a landslide.[25] In 1964 the island was visited by the British naval ship HMS Protector. On 17 December 1971, the entire island and its territorial waters were protected as a nature reserve.[2] A scientific landing was made in 1978, during which the underground temperature was measured to be 25 °C (77 °F).[26] In addition to scientific surveys,[17] a lifeboat was recovered at Nyrøysa, although no people were found.[26] The lifeboat belonged to a scientific reconnaissance vessel ("The scientific reconnaissance vessel "Slava-9" began his regular 13th cruise with the "Slava" Antarctic whaling fleet on 22 October 1958 ... On 27 November she got to Bouvet Island. A group of sailors landed but were unable to leave the island in time because of worsened weather and stayed on it for about 3 days. The people were withdrawn only by helicopter on 29 November"[27]).

The Vela Incident took place on 22 September 1979, on or above the sea between Bouvetøya and Prince Edward Islands, when the American Vela Hotel satellite 6911 registered an unexplained double flash. This observation has been variously interpreted as a nuclear test, meteor, or instrumentation glitch.[26][28][29][30]

Since the 1970s, the island has been visited frequently by Norwegian Antarctic expeditions. In 1977, an automated weather station was constructed, and for two months in 1978 and 1979 a manned weather station was operated.[22] In March 1985, a Norwegian expedition experienced sufficiently clear weather to allow the entire island to be photographed from the air, resulting in the first accurate map of the whole island, 247 years after its discovery.[31] The Norwegian Polar Institute established a 36-square-metre (390 sq ft) research station, made of shipping containers, at Nyrøysa in 1996. On 23 February 2006, the island experienced a magnitude 6.2 earthquake whose epicentre was about 100 km (62 mi) away,[32] weakening the station's foundation and causing it to be blown to sea during a winter storm.[33] In 2014, a new research station was sent from Tromsø in Norway, via Cape Town, to Bouvet. The new station is designed to house six people for periods of two to four months.[34]

In the mid-1980s, Bouvetøya, Jan Mayen, and Svalbard were considered as locations for the new Norwegian International Ship Register, but the flag of convenience registry was ultimately established in Bergen, Norway, in 1987.[35] In 2007, the island was added to Norway's tentative list of nominations as a World Heritage Site as part of the transnational nomination of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.[36]

Krill fishing in the Southern Ocean is subject to the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, which defines maximum catch quotas for a sustainable exploitation of Antarctic krill.[37] Surveys conducted in 2000 showed high concentration of krill around Bouvetøya. In 2004, Aker BioMarine was awarded a concession to fish krill, and additional quotas were awarded from 2008 for a total catch of 620,000 tonnes (610,000 long tons; 680,000 short tons).[38] There is a controversy as to whether the fisheries are sustainable, particularly in relation to krill being important food for whales.[39] In 2009, Norway filed with the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf to extend the outer limit of the continental shelf past 200 nautical miles (230 mi; 370 km) surrounding the island.[40]

The Hanse Explorer expedition ship visited Bouvet Island on 20 and 21 February 2012 as part of "Expédition pour le Futur". The expedition's goal was to land and climb the highest point on the island. The first four climbers (Aaron Halstead, Will Allen, Bruno Rodi and Jason Rodi) were the first humans to climb the highest peak. A time capsule containing the top visions of the future for 2062 was left behind. The next morning, Aaron Halstead led five other climbers (Sarto Blouin, Seth Sherman, Chakib Bouayed, Cindy Sampson, and Akos Hivekovics) to the top.[41]

Several amateur radio DX-peditions have been conducted to the island.[42][43][44]

Geography

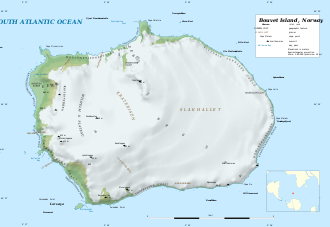

Bouvetøya is a volcanic island constituting the top of a volcano located at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the South Atlantic Ocean. The island measures 9.5 by 7 kilometres (5.9 by 4.3 mi) and covers an area of 49 square kilometres (19 sq mi),[23] including a number of small rocks and skerries and one sizable island, Larsøya.[45] It is located in the Subantarctic, south of the Antarctic Convergence,[46] which, by some definitions, would place the island in the Southern Ocean.[47] Bouvet Island is the most remote island in the world.[48] The closest land is Queen Maud Land of Antarctica, which is 1,700 kilometres (1,100 mi) to the south,[9] and Gough Island, 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) to the north.[49] The closest inhabited location is Tristan da Cunha island, 2,250 kilometres (1,400 mi) to the northwest.[23] To its west, the South Sandwich Islands lie about 1,900 km (1,200 mi) away, and to its east are the Prince Edward Islands, about 2,500 km (1,600 mi) away.

Nyrøysa is a 2-by-0.5-kilometre (1.2 by 0.3 mi) terrace located on the north-west coast of the island. Created by a rock slide sometime between 1955 and 1957, it is the island's easiest access point.[31] It is the site of the automatic weather station.[50] The north-west corner is the peninsula of Kapp Circoncision.[51] From there, east to Kapp Valdivia, the coast is known as Morgenstiernekysten.[52] Store Kari is an islet located 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) east of the cape.[53] From Kapp Valdivia, southeast to Kapp Lollo, on the east side of the island, the coast is known as Victoria Terrasse.[54] From there to Kapp Fie at the southeastern corner, the coast is known as Mowinckelkysten. Svartstranda is a section of black sand which runs 1.8 kilometres (1.1 mi) along the section from Kapp Meteor, south to Kapp Fie.[55] After rounding Kapp Fie, the coast along the south side is known as Vogtkysten.[56] The westernmost part of it is the 300 metres (980 ft) long shore of Sjøelefantstranda.[57] Off Catoodden, on the south-western corner, lies Larsøya, the only island of any size off Bouvetøya.[45] The western coast from Catoodden north to Nyrøysa, is known as Esmarchkysten. Midway up the coast lies Norvegiaodden (Kapp Norvegia)[58] and 0.5 kilometres (0.31 mi) off it the skerries of Bennskjæra.[59]

Ninety-three percent of the island is covered by glaciers, giving it a domed shape.[31] The summit region of the island is Wilhelmplatået, slightly to the west of the island's center.[17] The plateau is 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) across[60] and surrounded by several peaks.[17] The tallest is Olavtoppen, 780 metres (2,560 ft) above mean sea level (AMSL),[31] followed by Lykketoppen (766 metres or 2,513 feet AMSL)[61] and Mosbytoppane (670 metres or 2,200 feet AMSL).[62] Below Wilhelmplatået is the main caldera responsible for creating the island.[17] The last eruption took place 2000 BCE, producing a lava flow at Kapp Meteor.[60] The volcano is presumed to be in a declining state.[17] The temperature 30 centimetres (12 in) below the surface is 25 °C (77 °F).[31]

The island's total coastline is 29.6 kilometres (18.4 mi).[63] Landing on the island is very difficult, as it normally experiences high seas and features a steep coast.[31] During the winter, it is surrounded by pack ice.[23] The Bouvet Triple Junction is located 275 kilometres (171 mi) west of Bouvet Island. It is a triple junction between the South American Plate, the African Plate and the Antarctic Plate, and of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the Southwest Indian Ridge and the American–Antarctic Ridge.[64]

Climate

The island is located south of the Antarctic Convergence, giving it a marine Antarctic climate dominated by heavy clouds and fog. It experiences a mean temperature of −1 °C (30 °F),[31] with January average of 1 °C (34 °F) and September average of −3 °C (27 °F).[49] The monthly high mean temperatures fluctuate little through the year.[65] The peak temperature of 14 °C (57 °F) was recorded in March 1980, caused by intense sun radiation. Spot temperatures as high as 20 °C (68 °F) have been recorded in sunny weather on rock faces.[31] The island predominantly experiences a weak west wind.[49] In spite of these severe climate conditions, Bouvet Island actually is located four degrees of latitude closer to the equator than the southernmost tip of Norway, which is located at 58°N. Its latitude from a Scandinavian standpoint is instead located similarly to southern Denmark.

| Climate data for Bouvet Island | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.2 (50.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

5.2 (41.4) |

3.8 (38.8) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.7 (38.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

2.5 (36.5) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

1.8 (35.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

1.4 (34.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

1.5 (34.7) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−0.7 (30.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.3 (31.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−6.0 (21.2) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−14.8 (5.4) |

−15 (5) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

| Source 1: Météo climat stats[66] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Météo Climat [67] | |||||||||||||

Nature

The harsh climate and ice-bound terrain limits non-animal life to fungi (ascomycetes including symbiotic lichens) and non-vascular plants (mosses and liverworts). The flora are representative for the maritime Antarctic and are phytogeographically similar to the South Sandwich Islands and South Shetland Islands. Vegetation is limited because of the ice cover, although snow algae are recorded. The remaining vegetation is located in snow-free areas such as nunatak ridges and other parts of the summit plateau, the coastal cliffs, capes and beaches. At Nyrøysa, five species of moss, six ascomycetes (including five lichens), and twenty algae have been recorded. Most snow-free areas are so steep and subject to frequent avalanches that only crustose lichens and algal formations are sustainable. There are six endemic ascomycetes, three of which are lichenized.[50]

The island has been designated as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International because of its importance as a breeding ground for seabirds. In 1978–79 there were an estimated 117,000 breeding penguins on the island, consisting of macaroni penguin and, to a lesser extent, chinstrap penguin and Adélie penguin, although these were only estimated to be 62,000 in 1989–90. Nyrøysa is the most important colony for penguins, supplemented by Posadowskybreen, Kapp Circoncision, Norvegiaodden and across from Larsøya. Southern fulmar is by far the most common non-penguin bird with 100,000 individuals. Other breeding seabirds consist of Cape petrel, Antarctic prion, Wilson's storm petrel, black-bellied storm petrel, subantarctic skua, southern giant petrel, snow petrel, slender-billed prion and Antarctic tern. Kelp gull is thought to have bred on the island earlier. Non-breeding birds which can be found on the island include the king penguin, wandering albatross, black-browed albatross, Campbell albatross, Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross, sooty albatross, light-mantled albatross, northern giant petrel, Antarctic petrel, blue petrel, soft-plumaged petrel, Kerguelen petrel, white-headed petrel, fairy prion, white-chinned petrel, great shearwater, common diving petrel, south polar skua and parasitic jaeger.[50]

The only non-bird vertebrates on the island are seals, specifically the southern elephant seal and Antarctic fur seal, which both breed on the island. In 1998–99, there were 88 elephant seal pups and 13,000 fur seal pups at Nyrøysa. Southern Right whale, Humpback whale, Fin whale, Southern right whale dolphin, Hourglass dolphin, killer whale are seen in the surrounding waters.[68][50][69][70]

Politics and government

Bouvetøya is one of three dependencies of Norway.[71] Unlike Peter I Island and Queen Maud Land, which are subject to the Antarctic Treaty System,[72] Bouvetøya is not disputed.[63] The dependency status entails that the island is not part of the Kingdom of Norway, but is still under Norwegian sovereignty. This implies that the island can be ceded without violating the first article of the Constitution of Norway.[71] Norwegian administration of the island is handled by the Polar Affairs Department of the Ministry of Justice and the Police, located in Oslo.[73]

The annexation of the island is regulated by the Dependency Act of 24 March 1933. It establishes that Norwegian criminal law, private law and procedural law apply to the island, in addition to other laws that explicitly state they are valid on the island. It further establishes that all land belongs to the state, and prohibits the storage and detonation of nuclear products.[1] Bouvet Island has been designated with the ISO 3166-2 code BV[74] and was subsequently awarded the country code top-level domain .bv on 21 August 1997.[75] The domain is managed by Norid but is not in use.[76] The exclusive economic zone surrounding the island covers an area of 441,163 square kilometres (170,334 sq mi).[77]

In fiction

- The island figures prominently in the book A Grue of Ice (1962, published in the US as The Disappearing Island), an adventure novel based on Tristan da Cunha, Bouvet, and the mythical Thompson Island, by Geoffrey Jenkins.[78]

- Bouvet is the setting of the 2004 film Alien vs. Predator, in which it is referred to using its Norwegian name "Bouvetøya".[79]

See also

- List of islands of Norway

- List of Antarctic and subantarctic islands

References

Notes

- .bv allocated, but not used.

Citations

- "Lov om Bouvet-øya, Peter I's øy og Dronning Maud Land m.m. (bilandsloven)" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- "Forskrift om fredning av Bouvetøya med tilliggende territorialfarvann som naturreservat" (in Norwegian). Lovdata. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Berulfsen, Bjarne (1969). Norsk Uttaleordbok (in Norwegian). Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co (W Nygaard). p. 51.

- Mills, W.J. (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia. 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 96. ISBN 9781576074220.

- "An abandoned lifeboat at world's end | A Blast From The Past". allkindsofhistory.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Mills (2003): 96

- Barr (1987): 62

- Mill (1905): 47

- Barr (1987): 58

- Hough (1994): 248

- Burney (1817): 35

- Mills (2003): 434–35

- McGonigal (2003): 135

- Mill (1905): 106–107

- Simpson-Housley (1992): 60

- Barr (1987): 63

- P. E. Baker (1967). "Historical and Geological Notes on Bouvetøya" (PDF). British Antarctic Survey Bulletin (13): 71–84. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- R.K. Headland (ed.), Historical Antarctic sealing industry, Scott Polar Research Institute (Cambridge University), 2018, p.168. ISBN 978-0-901021-26-7

- A. R. H. and N. A. M. (1943). "Review: A New Chart of the Antarctic". The Geographical Journal. 102 (1): 29–34. doi:10.2307/1789367. JSTOR 1789367.

- "Thompson Island". Global Volcanism Program. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Kyvik (2008): 52

- Barr (1987): 64

- "Bouvetøya". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "South African expedition to Bouvetøya, 1955". Polar Record. 8 (54): 256–258. September 1956. doi:10.1017/S003224740004907X.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rubin (2005): 155

- Transactions of the Oceanographical Institute. p. 129.

- Hersh (1991): 271

- Rhodes (2011): 164–169

- Weiss, Leonard (2011). "Israel's 1979 Nuclear Test and the U.S. Cover-Up" (PDF). Middle East Policy. 18 (4): 83–95. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2011.00512.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Barr (1987): 59

- USGS. "M6.2 - Bouvet Island region". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- Jaklin, Patrick (20 July 2010). "Norsk feltstasjon tatt av naturkreftene ved Antarktis". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Molde, Eivind (7 February 2014). "Ny "ekstremstasjon" på Bouvetøya". NRK (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Kyvik (2008): 189

- "Islands of Jan Mayen and Bouvet as parts of a serial transnational nomination of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge system". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Schiermeier, Quirin (2 September 2010). "Ecologists fear Antarctic krill crisis". Nature. 467 (15): 15. doi:10.1038/467015a. PMID 20811427. Archived from the original on 13 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Molde, Eivind (2 March 2008). "Satsar på krill – eit nytt oljeeventyr". Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Haram, Øyvind Andre (5 November 2007). "Norge tek maten frå kvalen". Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Cordero-Moss, Giuditta. "The Law applicable to the Continental Shelf and in the Exclusive Economic Zone" (PDF). University of Oslo. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- "Making history summiting of the most remote land on earth". EXPEDITION POUR LE FUTUR. 4 March 2012. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 November 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Larsøya". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- "Antarctic Convergence". Geographic Names Information System. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "The Antarctic convergence". United Nations Environment Programme/GRID-Arendal. 25 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Volcanology Highlights". Global Volcanism Program. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Bouvetøya". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- Hyser, Onno. "Bouvetøya" (PDF). BirdLife International. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Kapp Circoncision". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Kapp Valdivia". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Store-Kari". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Kapp Lollo". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Svartstranda". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Vogtkysten". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Sjøelefantstranda". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Norvegiaodden". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Bennskjæra". Norwegian Polar Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Bouvet". Global Volcanism Program. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2012.

- "Lykke Peak". Geographic Names Information System. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- "Mosby Peak". Geographic Names Information System. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- "Bouvet Island". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 8 October 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Mitchell, Neil C.; Livermore, Roy A.; Fabretti, Paola; Carrara, Gabriela (2000). "The Bouvet triple junction, 20 to 10 Ma, and extensive transtensional deformation adjacent to the Bouvet and Conrad transforms" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 105 (B4): 8279–8296. Bibcode:2000JGR...105.8279M. doi:10.1029/1999JB900399. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Monthly Averages for Bouvet Island". Climate Zone. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2011.

- "Moyennes 1981-2010 Norvege (Atlantique Sud)" (in French). Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Météo Climat stats for Ile Bouvet". Météo Climat. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- https://academic.oup.com/jhered/article/111/3/263/5826886

- https://litografa.wixsite.com/artiolaphotographer/whales

- https://www.nhm.uio.no/fakta/zoologi/fugl/ringmerking/PDF/Bouvet_Atlantic.pdf

- Gisle (1999): 38

- Barr (1987): 65

- "Polar Affairs Department". Norwegian Ministry of the Environment. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- Takle, Mona Takle; Vassenden, Kåre (March 1998). "Country classifications in migration statistics – present situation and proposals for a Eurostat standard" (PDF). United Nations Statistical Commission and United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Delegation Record for .BV". Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. 13 November 2009. Archived from the original on 13 August 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "The .bv and .sj top level domains". Norid. 3 August 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- "EEZ Waters of Bouvet Isl. (Norway)". University of British Columbia. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- Jenkins, Geoffrey. 1962. A Grue of Ice London: Collins. 320pp.

- "AVP: Alien vs. Predator (2004) - IMDb". imdb.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

Sources

- Barr, Susan (1987). Norway's Polar Territories. Oslo: Aschehoug. ISBN 82-03-15689-4.

- Burney, James (1817). A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea Or Pacific Ocean. V.

- Hersh, Seymour (1991). The Samson option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. Random House. ISBN 0-394-57006-5.

- Hough, Richard (1994). Captain James Cook. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-82556-1.

- Kyvik, Helga, ed. (2008). Norge i Antarktis (in Norwegian). Oslo: Schibsted Forlag. ISBN 978-82-516-2589-0.

- Gisle, Jon, ed. (1999). Jusleksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget. ISBN 8257308625.

- McGonigal, David (2003). Antarctica. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-2980-8.

- Mill, Hugh Robert (1905). The Siege of the South Pole. London: Alston Rivers.

- Mills, William James (2003). Exploring Polar Frontiers: a historical encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576074226.

- Rhodes, Richard (2011). Twilight of the Bombs: Recent Challenges, New Dangers, and the Prospects for a World Without Nuclear Weapons. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-38741-7.

- Rubin, Jeff (2005). Antarctica. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-094-5.

- Simpson-Housley, Paul (1992). Antarctica: Exploration, Perception and Metaphor. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-08225-9.

External links

- The Most Remote Island in the World Sometimes Interesting. 11 November 2012

- Amateur Radio DX Pedition to Bouvet Island 3Y0Z

- Bouvet Island, the most remote island in the World Random-Times.com. June 2018'