Bodrum

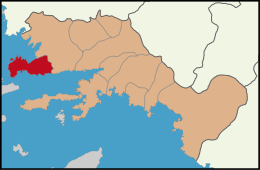

Bodrum (Turkish pronunciation: [ˈbodɾum]) is a district and a port city in Muğla Province, in the southwestern Aegean Region of Turkey. It is located on the southern coast of Bodrum Peninsula, at a point that checks the entry into the Gulf of Gökova, and is also the center of the eponymous district. The city was called Halicarnassus of Caria in ancient times and was famous for housing the Mausoleum of Mausolus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Built by the Knights Hospitaller in the 15th century, Bodrum Castle overlooks the harbour and the marina. The castle includes a museum of underwater archaeology and hosts several cultural festivals throughout the year. The city had a population of 36,317 in 2012. It takes 50 minutes via boat to reach Kos from Bodrum, with services running multiple times a day by at least three operators.

Bodrum | |

|---|---|

District of Muğla Province | |

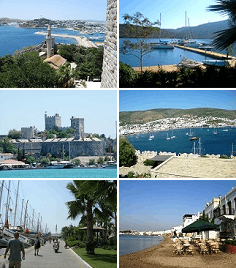

Clockwise from top left: 1st: View of Bodrum from castle of St. Peter, 2nd: Port Atami, 3rd: A view of Bodrum, 4th: Seaside at Bodrum , 5th: Marina in Bodrum, 6th: Bodrum Castle. | |

Bodrum  Bodrum  Bodrum | |

| Coordinates: 37°02′00″N 27°26′00″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Muğla |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ahmet Aras[1] (CHP) |

| • Kaymakam | Bekir Yılmaz[2] |

| Area | |

| • District | 656.06 km2 (253.31 sq mi) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Urban | 36,401[4] |

| Website | www.bodrum.bel.tr |

Etymology

In classical antiquity Bodrum was known as Halicarnassus (Ancient Greek: Ἁλικαρνασσός,[5] Turkish: Halikarnas), a major city in ancient Caria. The suffix -ᾱσσός (-assos) of Greek Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός is indicative of a substrate toponym, meaning that an original non-Greek name influenced or established the place's name.

It has been proposed that -καρνᾱσσός (-carnassos) part is cognate with Luwian word "ha+ra/i-na-sà", which means fortress.[6] If so, city's ancient name was probably borrowed from Carian, a Luwic language spoken alongside Greek in Western Anatolia. The Carian name for Halicarnassus has been tentatively identified with 𐊠𐊣𐊫𐊰 𐊴𐊠𐊥𐊵𐊫𐊰 (alos k̂arnos) in inscriptions.[7]

The modern name Bodrum derives from the town's medieval name Petronium, which has its roots in the Hospitaller Castle of St. Peter (see history).

History

Halicarnassus (Ancient Greek: Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός, romanized: Halikarnassós or Ἀλικαρνασσός Alikarnassós; Turkish: Halikarnas) was an ancient Greek city at the site of modern Bodrum in Turkey. Halicarnassus was founded by Dorian Greeks, and the figures on its coins, such as the head of Medusa, Athena or Poseidon, or the trident, support the statement that the mother cities were Troezen and Argos.[8] The inhabitants appear to have accepted Anthes, a son of Poseidon, as their legendary founder, as mentioned by Strabo, and were proud of the title of Antheadae. The Carian name for Halicarnassus has been tentatively identified with Alosδkarnosδ in inscriptions.

At an early period Halicarnassus was a member of the Doric Hexapolis, which included Kos, Cnidus, Lindos, Kameiros and Ialysus; but it was expelled from the league when one of its citizens, Agasicles, took home the prize tripod which he had won in the Triopian games, instead of dedicating it according to custom to the Triopian Apollo. In the early 5th century Halicarnassus was under the sway of Artemisia I of Caria (also known as Artemesia of Halicarnassus [9]), who made herself famous as a naval commander at the battle of Salamis. Of Pisindalis, her son and successor, little is known; but Lygdamis, the tyrant of Halicarnussus, who next attained power, is notorious for having put to death the poet Panyasis and causing Herodotus, possibly the best known Halicarnassian, to leave his native city (c. 457 BC).[10]

The city later fell under Persian rule. Under the Persians, it was the capital city of the satrapy of Caria, the region that had since long constituted its hinterland and of which it was the principal port. Its strategic location ensured that the city enjoyed considerable autonomy. Archaeological evidence from the period such as the recently discovered Salmakis (Kaplankalesi) Inscription, now in Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, attest to the particular pride its inhabitants had developed.[11]

Alexander the Great laid siege to the city after his arrival in Carian lands and, together with his ally, the queen Ada of Caria, captured it after fighting in 334 BCE.

Mausolus

Mausolus ruled Caria from here, nominally on behalf of the Persians and independently in practical terms, for much of his reign from 377 to 353 BC. When he died in 353 BC, Artemisia II of Caria, who was both his sister and his widow, employed the ancient Greek architects Satyros and Pythis, and the four sculptors Bryaxis, Scopas, Leochares and Timotheus to build a monument, as well as a tomb, for him. The word "mausoleum" derives from the structure of this tomb. It was a temple-like structure decorated with reliefs and statuary on a massive base. Today only the foundations and a few pieces of sculpture remain.

Petronium

.jpg)

Crusader Knights arrived in 1402 and used the remains of the Mausoleum as a quarry to build the still impressively standing Bodrum Castle (Castle of Saint Peter), which is a well-preserved example of the late Crusader architecture in the east Mediterranean. The Knights Hospitaller (Knights of St. John) were given permission to build it by the Ottoman sultan Mehmed I, after Tamerlane had destroyed their previous fortress located in İzmir's inner bay. The castle and its town became known as Petronium, whence the modern name Bodrum derives.

In 1522, Suleiman the Magnificent conquered the base of the Crusader knights on the island of Rhodes, who then relocated first briefly to Sicily and later permanently to Malta, leaving the Castle of Saint Peter and Bodrum to the Ottoman Empire.

20th century

Bodrum was a quiet town of fishermen and sponge divers until the mid-20th century; although, as Mansur points out, the presence of a large community of bilingual Cretan Turks, coupled with the conditions of free trade and access with the islands of the Southern Dodecanese until 1935, made it less provincial.[12] The fact that traditional agriculture was not a very rewarding activity in the rather dry peninsula also prevented the formation of a class of large landowners. Bodrum has no notable history of political or religious extremism either. A first nucleus of intellectuals started to form after the 1950s around the writer Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı, who had first come here in exile two decades before and was charmed by the town to the point of adopting the pen name Halikarnas Balıkçısı ('The Fisherman of Halicarnassus').[13]

Geography

Climate

Bodrum has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Csa in the Köppen climate classification). Winter average is around 15 °C (59 °F) and in the summer 34 °C (93 °F), with very sunny spells. Summers are hot and mostly sunny and winters are mild and humid.[14]

| Climate data for Bodrum | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.1 (73.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.7 (83.7) |

30.8 (87.4) |

39.0 (102.2) |

42.3 (108.1) |

46.8 (116.2) |

45.0 (113.0) |

39.8 (103.6) |

38.9 (102.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

46.8 (116.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

26.0 (78.8) |

31.2 (88.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

34.0 (93.2) |

30.3 (86.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

23.9 (75.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.4 (52.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

28.3 (82.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.7 (54.9) |

19.0 (66.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.3 (46.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

20.8 (69.4) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

15.2 (59.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −1.6 (29.1) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

2.8 (37.0) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.6 (54.7) |

16 (61) |

18.5 (65.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

2.0 (35.6) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 134.1 (5.28) |

107.9 (4.25) |

74.0 (2.91) |

39.1 (1.54) |

18.4 (0.72) |

7.5 (0.30) |

1.3 (0.05) |

8.5 (0.33) |

20.8 (0.82) |

40.5 (1.59) |

97.7 (3.85) |

156.2 (6.15) |

706 (27.79) |

| Average rainy days | 12.3 | 11.2 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 3.7 | 2.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 8.8 | 13.2 | 77.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148.8 | 151.2 | 198.4 | 225 | 285.2 | 318 | 337.9 | 322.4 | 273 | 223.2 | 168 | 139.5 | 2,790.6 |

| Source: Devlet Meteoroloji İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü [15] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for water temperatures in Bodrum | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.5 (76.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.8 (80.2) |

25.3 (77.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

19.8 (67.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.2 (59.4) |

14.9 (58.8) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.3 (59.5) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

20.0 (68.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Source: seatemperature.org[16] | |||||||||||||

Main sights

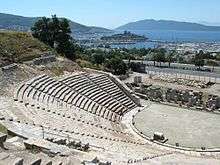

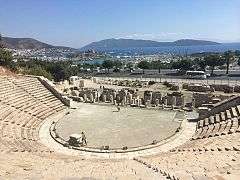

The Castle of St. Peter, also known as Bodrum Castle, is one of the major attractions on the peninsula. The castle was built by the Knights Hospitaller during 15th century and the walls of fortification contains some pieces of the Mausoleum ruins, as it was used as a source for construction materials. The Castle of Bodrum retains its original design and character of Knights' period and reflects Gothic architecture.[17] It also contains the Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, a museum opened by Turkish Government in 1962 for the underwater discoveries of ancient shipwrecks in the Aegean Sea.[18] In 2016 the castle was inscribed in the Tentative list of World Heritage Sites in Turkey.[17] The castle is currently under renovation since 2017 and only some parts of it is accessible for touristic purposes.[19]

Built in 4th century BC, ruins of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus is also one of the main sights in Bodrum. It was a tomb designed by the Greek architects and built for Mausolus, a satrap in the Persian Empire, and his sister-wife Artemisia II of Caria.[20] The structure was once considered as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World,[21] but by the 12th century CE had mostly been destroyed.[22][23][24] Today ruins of the tomb attracts both domestic and international tourists.[25] It is planned to turn the ruins into an open-air museum in future years.[26]

Apart from Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, there are also other museums that are located on the peninsula. Zeki Müren Art Museum is a museum dedicated to Turkish classical musician Zeki Müren. After his death, the house in which the artist lived in Bodrum for the last years of his life was transformed into Zeki Müren Art Museum by the order of the Ministry of Culture and was opened to the public on 8 June 2000.[27] Bodrum Maritime Museum is another museum of Bodrum that targets to conduct activities regarding classification, exhibition, restoration, conservation, storage and safekeeping of the historical documents, works and objects important for the maritime history of the city.[28] Bodrum City Museum is a minor museum in city center that presents the general history of Bodrum peninsula.[29]

Demographics

The population for the town of Bodrum was 35,795 in the 2012 census. The surrounding towns & villages had an additional 100,522, for a total for the district of 136,317.[30]

Historical population

| Year | Total | Urban | Rural |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1965[31] | 25.811 | 5.136 | 20.675 |

| 1970[32] | 27.383 | 6.077 | 21.306 |

| 1975[33] | 29.490 | 7.858 | 21.632 |

| 1980[34] | 32.517 | 9.799 | 22.718 |

| 1985[35] | 37.966 | 12.949 | 25.017 |

| 1990[36] | 56.821 | 20.931 | 35.890 |

| 2000[37] | 97.826 | 32.227 | 65.599 |

| 2007[38] | 105.474 | 28.575 | 76.899 |

| 2008[39] | 114.498 | 30.688 | 83.810 |

| 2009[40] | 118.237 | 31.590 | 86.647 |

| 2010[41] | 124.820 | 33.258 | 91.562 |

| 2011[42] | 130.990 | 34.866 | 96.124 |

| 2012[43] | 136.317 | 35.795 | 100.522 |

| 2013[44] | 140.716 | 140.716 | N/A |

| 2014[45] | 152.440 | 152.440 | N/A |

| 2015[46] | 155.815 | 155.815 | N/A |

| 2016[47] | 160.002 | 160.002 | N/A |

Government

The district of Bodrum is one of 957 in Turkey. It is in Muğla Province which is part of the Aydin Subregion, which, in turn, is part of the Aegean Region. Bodrum has become a sub-district in 1871 and a district of Muğla Province in 1872. Bodrum Municipality serves with its 18 directorates and subsidiary units in the entire of Bodrum Peninsula which has an area of 689 km2 and a coastline of 215 km length. The organizational structure of Bodrum Municipality is composed of the Mayor, 4 Deputy Mayors and 18 Directorates.[48]

Bodrum Municipality has served as the sole district municipality in Bodrum region for many years. Afterwards, with the significant increase in the population of peninsula, a town municipality has been founded with the name of Karatoprak (Turgutreis) in 1967. In conjunction with increased settlements to the towns and villages of Bodrum, Mumcular (1972), Yalıkavak (1989) and Gündoğan Municipalities (1992) were established.[48]

Following the new municipality law introduced in 1999, many villages in Bodrum turned into towns in the same year. Ortakent-Yahşi with the integration of Ortakent and Yahşi villages, Göltürkbükü with the integration of Gölköy and Türkbükü, Yalı with the integration of Yalı and Kızılağaç villages were established. In the same year Gümüşlük , Konacık and Bitez Municipalities were founded, making the number of the municipalities across Bodrum Peninsula 11.[48]

After Muğla Province received Metropolitan Municipality status, these town municipalities were closed and all towns across the province were integrated into Bodrum city. From 30 March 2014 the peninsula started to be governed as a sole municipality.[48]

Economy

During the 20th century the city's economy was mainly based on fishing and sponge diving. Even though naked sponge diving's past can be traced back at least three thousand years in the Aegean region, modern sponge diving started to be prevalent in Bodrum after the Koan and Cretan immigrants settled in the city in the early 20s, after the population exchange between Greece and Turkey.[49] During its golden age between 1945 and 1965, there were close to 150 boats engaged in sponge diving activities in Bodrum. However, due to the sponge diseases, artificial sponge production and ban on sponge diving eventually ended this lucrative industry in Bodrum.[49]

Over the years, tourism became one of the major activities and main income source of local communities in Bodrum.[50] The abundance of visitors has also enlivened Bodrum's retail and service industry. Leather goods, particularly for traditional woven sandals are well known products in the town. Other traditional goods such as tangerine flavored Turkish delight, Nazar amulets and handicrafts are also main souvenirs that are sold in the city.[51]

Apart from small shopping facilities the city hosts some larger shopping centers like Midtown and Oasis. There are also Yacht and small ship accommodation oriented marinas such as Milta Bodrum Marina[52], D-Marin Turgutreis,[52] and award-winning Yalıkavak Marina.[53]

The Carian Trail also pass by Bodrum and surrounding Kızılağaç and Pedasa ruins, which attracts hikers both from inside and outside of Turkey.[54]

Culture

.jpg)

Architecture

Traditional Bodrum houses are characterized by their prismatic shapes, simplistic designs and locally sourced building materials like stone, wood, clay and cane.[55] They also tend to have white dominated exterior walls with some blue parts (doors, windows).[56] Apart from the historic tradition, the reason for a white exterior is associated with the bug and scorpion repellent properties of lime, which is found in white paint. Blue is also believed to protect against bad luck by locals (similar to Nazar).[56]

According to Muğla Municipality, in order to acquire a building permit one have to accept to paint the walls of the new building white. Use of any paint other than white on the exterior walls of a building has been officially banned by Muğla Governor Temel Koçaklar at 2006.[57] This was implemented to protect the historical fabric and cultural identity of the city.[57]

Events and festivals

Bodrum International Ballet Festival is being held in Bodrum every summer since 2002.[58] Furthermore, Bodrum has also been hosting Bodrum International Biennial since 2014.[59] Bodrum Baroque Music Festival is another annual music event held in the city.[60]

Transportation

Airports

There are no airports in the city. Two airports serve the city. Milas–Bodrum Airport is located 36 kilometres (22 mi) northeast of Bodrum, with both domestic and international flights.[61] Kos Island International Airport, 70 kilometres (43 mi) to the SW, located in Andimachia, Greece, accessible by boats from Bodrum across a 20 kilometres (12 mi) stretch of the Aegean Sea. Aside from year-round flights to Greek destinations, Kos airport's traffic is seasonal.

Bus

Main bus station is located in the city center and it accommodates intercity bus services to other locations in Turkey. There are around 47 different bus companies on the main station, which have routes mainly to major cities like İstanbul, Ankara and İzmir.[62]

Most of the public transportation in the city is based on local share taxis called "dolmuş". Each of these privately owned minibuses display their particular route on signboards behind their windscreens.[63] The word derives from Turkish for "full" or "stuffed", as these share taxis depart from the terminal only when a sufficient number of passengers have boarded.[64] Apart from these minibuses Muğla Municipality also has a scheduled bus service program between towns on Bodrum peninsula.[65] Public transportation between major towns such as Gümbet, Bitez, Turgutreis and main bus station is non-stop.[66]

Port

The port has ferries to other nearby Turkish and Greek ports and islands.[61] Bodrum has three large marinas and cruise berths. The first marina Milta, located in the center of Bodrum. The second marina is located in Turgutreis, and the third Palmarina in Yalikavak.

Wildlife

Maquis shrubland biome, which is the typical vegetation of Mediterranean climate, is widespread in Bodrum, especially near the coastal areas. Forests also cover 61.3% of the district.[67] Conifers such as pines, larches, stone pines, cedars and junipers are the dominant trees in the region.[68] Forested areas are prone to fires and wildfires are common in district's history.[69] 95% of forest fires is believed to be caused by human activities in Turkey and there are concerns that forests are deliberately being put on fire to enlarge the city. Ruling party AKP has been criticized by media for giving building permits on burnt and deforested area to construct new hotels.[70][71]

Wild boars and foxes are prevalent in the area, as other animals like pygmy cormorants, Dalmatian pelicans and lesser kestrels. The region is also home to endangered and internationally protected Mediterranean monk seal.[67]

Notable people

- Herodotus – ancient Greek historian

- Scylax of Caryanda – ancient explorer

- Julian of Halicarnassus was a bishop in the early 6th century.[72]

- Mausolus – Carian ruler

- Artemisia II of Caria – Carian ruler

- Dionysius – ancient Greek historian and teacher of rhetoric in the Roman period

- Turgut Reis – Ottoman Turkish admiral

- Halikarnas Balıkçısı, literally 'The Fisherman of Halicarnassus' or Cevat Şakir Kabaağaçlı – Turkish writer born in Istanbul, resident of Bodrum for decades and a symbol for the town

- Neyzen Tevfik – Turkish ney virtuoso and pundit[73]

- Zeki Müren – Turkish singer born in Bursa, resident of Bodrum for decades and a symbol for the town[74]

- Janet Akyüz Mattei – director of the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) from 1973 to 2004[75]

- Abdurrahman Nafiz Gürman - military officer in the Ottoman and Turkish armies[76]

- Zeynep Çamcı - Turkish actress [77]

Twin towns — sister cities

Bodrum is twinned with:

See also

- Milas-Bodrum Airport

- Kos Airport

- Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology (within Bodrum Castle)

- Turgutreis

- Blue Cruise

- Marinas in Turkey

- Gulet

- Foreign purchases of real estate in Turkey

- Turkish Riviera

- Gümüşlük, a neighborhood north of Bodrum

References

- "Özgeçmiş". Bodrum Belediyesi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Kaymakam Bekir YILMAZ". www.bodrum.gov.tr. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- "Turkey: Registered Population". City Population. Retrieved 2014-04-11.

- Ἁλικαρνασσός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, at Perseus project

- Ilya Yakubovich. "Phoenician and Luwian in Early Age Cilicia". Anatolian Studies 65 (2015): 44, doi:10.1017/S0066154615000010 Archived 2016-09-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- Lajara, Ignacio-Javier Adiego (2007). The Carian Language. BRILL. ISBN 9789004152816.

- Hogarth, David George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 837.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 665.

- "Herodotus". Suda. At the Suda On Line Project.

- Signe Isager (1998). "The Pride of Halicarnassus" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 123 p. 1-23.

- Fatma Mansur (1972). Bodrum. Brill Publishers. ISBN 90-04-03424-2.

- Bodream, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, Anagramme Ed., 2010, pp.62-66

- "World Water Temperature | Sea Temperatures". www.seatemperature.org. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- "İl ve İlçelerimize Ait İstatistiki Veriler- Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü". Dmi.gov.tr. 1971-11-30. Archived from the original on 2012-08-01. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- https://www.seatemperature.org/middle-east/turkey/bodrum.htm

- "The Bodrum Castle". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "Bodrum Museum". Bodrum Museum. 2010-03-23. Retrieved 2012-06-26.

- Codingest (2019-05-18). "Bodrum Kalesi Ziyarete Açıldı..." Kent TV (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Kostof, Spiro (1985). A History of Architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-19-503473-2.

- "Mausoleum of Halicarnassus". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- "The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus". Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- "The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus". Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Gloag, John (1969) [1958]. Guide to Western Architecture (Revised ed.). The Hamlyn Publishing Group. p. 362.

- "Halikarnas Mozolesi'nin kalıntıları dahi ilgi çekiyor". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Halikarnas Mozolesi Açık Hava Müzesi projesi anlatıldı haberi". Arkeolojik Haber. Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Sanat Güneşi Şarkıları ile Anılacak". Haberler.com. 18 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- "About Us – Bodrum Maritime Museum". Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- "Bodrum'da kent müzesi kapılarını halka açtı!". EGE ALTERNATİF GAZETESİ (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-12-01.

- Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012 Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine/

- "1965 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "1970 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "1975 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "1980 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "1985 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "1990 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2000 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2007 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2008 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2009 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2010 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2011 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "2012 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 20 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- "2013 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 15 February 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- "2014 genel nüfus sayımı verileri". Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Archived from the original (html) on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- "2015 genel nüfus sayımı verileri" (html). Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "2016 genel nüfus sayımı verileri" (html). Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- "About us - Bodrum Belediyesi". Bodrum Municipality. Retrieved 2019-09-01.

- "Sponge-fishing – Bodrum Maritime Museum". Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- Bodrum

- "Bodrum'da Hediyelikler Harika Bodrumlife Sayı 24 Ağu-2012". www.bodrumlife.com.tr. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- "Türkiye'deki Marinalar". www.denizticaretodasi.org.tr. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- "TYHA awards world's best marinas for 2018/19". britishmarine.co.uk. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- Yedig, Serhan. "Karya Yolu'nda baharla kucaklaşma". www.hurriyet.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-09-24.

- Aysel, Nezih (May 2003). "Bodrum-Ortakent (Müsgebi)'de Geleneksel Ev Tipleri Üzerine Bir İnceleme". Dergipark. 3: 17–18.

- "Bodrum'un beyazı 'haşereye' mavisi 'nazara'". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- "Bodrum Evlerinin Rengi Beyaz Olacak". www.yapi.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- Alin Taşçıyan (4 August 2013). "Hürrem Sultan, Spartaküs ve Amazonlar Bodrum Kalesi'nde". Star. Archived from the original on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Uluslararası Bodrum Bienali başlıyor". Hürriyet. 6 September 2015. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "Barok müzik festivali başladı". Hürriyet. 6 September 2015. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- "BODRUM | Place to Visit | Things to Do | Famous For". Very Turkey. Retrieved 2014-03-20.

- "Bodrum Otogarındaki Şehirlerarası Otobüs Şirketleri". bodrumotogar.com. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- Turkish Dolmus Taxi or Minibus turkeytravelplanner.com

- Bus Services in North Cyprus Archived 2010-08-23 at the Wayback Machine essentialcyprus.com, January 28, 2009.

- "T.C. Muğla Büyükşehir Belediyesi Otobüs Sefer Saatleri". www.mugla.bel.tr. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- "Muğla Büyükşehir Belediyesi - Bodrum Belediye Otobüsleri ve Dolmuşları". bodrumotogar.com. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- "Bodrum'un Coğrafi Konumu - Bodrum Chamber of Commerce, BODTO Web Portal". www.bodto.org.tr. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- "Bodrum - İklim ve Bitki Örtüsü". bodrum.net.tr - Bodrum. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- "Forest fires in Bodrum, Manavgat contained - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- "Fotoğrafların Muğla Güvercinlik'te yangın sonrası yapılaşmaya açılan yerleri gösterdiği iddiası". teyit.org (in Turkish). 2019-04-16. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- "Bodrum'da çevre cinayeti". NTV (in Turkish). 2011-11-24. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- Cyril Hovorun, Will, Action and Freedom: Christological Controversies in the Seventh Century (Leiden, Brill, 2008, ISBN 978-90-04-16666-0). Page 28: "Julian of Halicarnassus. One such question was raised by Julian, bishop of Halicarnassus (d. after 527)."

- "Neyzen Tevfik" (in Turkish). TC Kültür Bakanlığı. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- "Zeki Müren Sanat Müzesi" (in Turkish). Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- "Dr. Akyüz-Mattei'nin adı yaşatılacak" (in Turkish). NTV. 2004-09-30. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- "Nafiz Gürman" (in Turkish). Biyografya. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- "Zeynep Çamcı" (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- "Kosova'nın Prizren Şehri ile Bodrum kardeş şehir olacak" (in Turkish). Bodrum Municiplity Official Site. 2019-08-27. Archived from the original on 2019-08-27. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

- "Bodrum Belediyesi". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- "Eskişehir′in kardeş şehirleri" (in Turkish). Eskişehir Metropolitan Municipality Official Site. Archived from the original on 21 February 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- "Bodrum ile Wakayama kardeş şehir oluyor" (in Turkish). Bodrum Municiplity Official Site. 2019-08-27. Archived from the original on 2019-08-27. Retrieved 2019-08-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bodrum. |

- Turkish Republic Municipalities of Bodrum

- Ministry of Culture and Tourism: Bodrum

- Bodrum Webcam

.jpg)